Still Armed, Still Dangerous

( Uncredited / AP Images )

KATYA ROGERS Oh, hi, it's me, you. I have a favor to ask – don't hang up. It's not a huge favor, but it's something that I need you to do. The last few years have been rough for so many reasons. And you know, we've covered it all. And you, our loyal listeners have been right by our side. We rely on you. You rely on us. You know how it goes. You always come through for us when we ask you to except when you don't...What we've observed actually is that when the country is in a deep crisis, like really deep, the public radio listener, you guys, you step up. You feel the urgency. You donate. But then when the news temperature drops even by a few degrees and it feels less like we're on a precipice, you just don't feel as compelled to give. You know, you put the pocketbook away. Or maybe you just feel exhausted by the relentless nature of it all. And you want to check out for a bit. We're all human. I understand the impulse. I really, really do. But here's the deal. If we don't keep this show financially supported, it will go away. It's that simple. I mean, how would you feel if the next time the news cycle spins completely out of control and you turn to your favorite podcast to help you through it – and we're just not there? OK, picture it, it's not like it can't happen. Here's the solution, become a sustaining member, then you don't have to think about it again for another year, 10 bucks a month works out to about two bucks a week. Do two shows a week. Stick a dollar or so. I mean, you probably paid twice that for your coffee this morning. And hey, here's an incentive for you. If you become a sustaining member before the end of April, you'll be entered to win one of Brooke's crocheted hats. You know you've always wanted one, to be honest. She spent most of the pandemic crocheting, so we have a ton. Like a pile. The odds are good here, this is not the lottery. You could walk away with a hat. So, do it now. You'll feel good. We’ll feel good. It'll be great. Go to onthemedia.org hit support or text OTM to 7-0-1-0-1. It would really mean the world to us. Thank you so much.

GIDEON ROSE When we were in the position of the Russians trying to conquer other countries that didn't want to be conquered, we convinced ourselves that those downsides didn't exist.

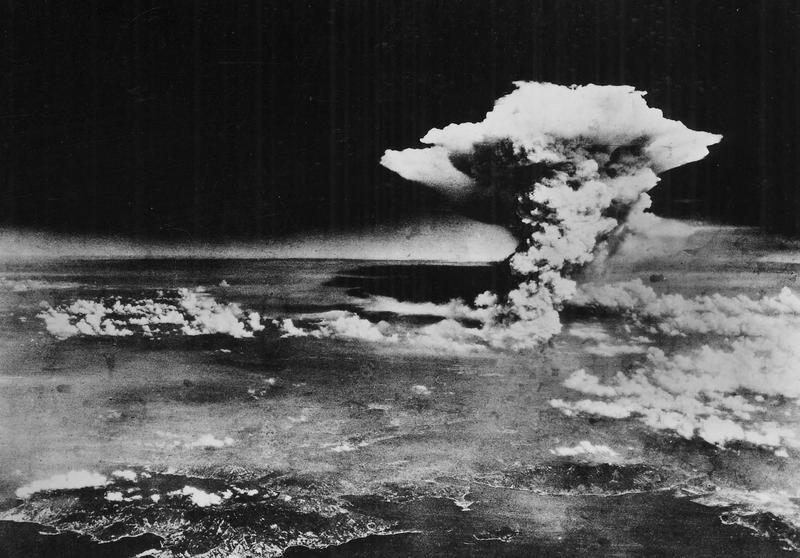

BROOKE GLADSTONE What can the US learn from being on the other side of an invasion gone awry? From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. Also on this week's show, the nuclear threat looms, but even Putin understands the risks.

KRISTIN ven BRUUSGAARD He, too, understands that crossing this threshold would give him a historical legacy that he perhaps would not want.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Plus, a historian explains how we compartmentalize the existential threat of nukes.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN If your idea of nuclear bomb going off as the screen fades to white and the credits start rolling, you end up not taking that seriously as something that's likely to happen. You put that in the part of your brain you put your awareness of your own inevitable death.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It's all coming up after this.

[END OF BILLBOARD]

BROOKE GLADSTONE From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. At the time of recording, we still don't know if the latest negotiations between Ukraine and Russia will bear fruit, or whether Putin will ever honor his pledge to ease bombing or for how long. What is clear is that his invasion hasn't gone the way he expected.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT It's not just that the Russians don't have gas or other means to fight, but it's the actions of the Ukrainian army that led to destroying their lines of communication, so they can't replenish their food, fuel and other equipment, said Sergey Canarsie of the city's police and military advisers.

NEWS REPORT Ukraine is pressing its counterattack on several fronts, claiming new victories on the battlefield. Government officials here say Ukrainian forces have retaken several villages around Kharkiv in the east. That's a city that's held out against Russian assaults.

NEWS REPORT In another major development tonight, a senior U.S. defense official now says Russian forces that had taken control of the city of Kherson are no longer in full control of that city. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE These Russian setbacks have led some commentators to begin throwing around words like win and lose. But the distinction between those terms is getting blurrrier by the minute.

[CLIP]

CHRIS WALLACE If he wins, he loses, and if he loses, he loses. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE CNN's Chris Wallace.

[CLIP]

CHRIS WALLACE And he's a pariah. How does it go back to meeting with world leaders? How does Russia, as long as he's in power, go back to having an economy? So what's his end game? [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE In a recent issue of foreignaffairs.com Gideon Rose wrote a shocking aspect of the Ukraine war, everybody agrees, is how stupid it is. What kind of idiot invades a country without a plan for how it all ends? This lesson might be the cringiest of all for Washington to learn, however, because entering wars without plans for ending them is an American national pastime.

GIDEON ROSE Everybody convinces themselves that will be different this time. Hey, we took over Vietnam from the French. We literally stepped into the French Jews and told ourselves, It's OK will do better because we have pure motives and they're just bad colonialists.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Gideon served on the National Security Council under Clinton and as a fellow in US foreign policy at the Council on Foreign Relations.

GIDEON ROSE We may believe that this is about democracy or about rights or about authoritarianism in most of these conflicts. What motivates most of the players is, are you part of my group or are you part of the enemy group? And we have been the white colonial foreigner in most of these conflicts, and now Russia is. Essentially these are colonial wars at their most basic level. And if you get in a colonial war, the people who are trying to resist colonialism are more motivated because for them, it's an existential choice, whereas for you, it's an optional choice.

BROOKE GLADSTONE OK, so let's talk about the end game.

GIDEON ROSE We tend to think of wars. It's like a boxing match in which the problem is to beat up the other person and get him to say, Uncle. Just knock them out. But unlike a boxing match, the real problems with wars start when the fighting stops, which is you have to have a stable political solution afterwards. But because we don't tend to think about the politics of wars, we're always surprised by the challenges in governing a country when it starts to fall apart. And then you have a Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld, saying, "Hey, stuff happens" as if you couldn't plan for that stuff. You can. So the Russians are being excoriated for not having a plan for what to do if their war didn't go successfully. And that's exactly what has been the characteristic of American national security policy for half a century. In Vietnam, we thought basically, if we keep bombing and pounding the enemy, that eventually they must give in because they're a weak, poor country. They never did, and so we were stuck having escalated to a huge level having to withdraw and back out. In the Iraq War, they convinced themselves that a few Iraqi exiles, led by Ahmed Chalabi, would be able to run the country, greeted like liberators and provide a sort of puppet government that we could walk away from. That was a fantasy, and that was when Petraeus stopped dealing with the aftermath makes his famous comment to Rick Atkinson "tell me how this ends." And in Afghanistan, we also didn't have a great plan. It was to put in a new government and hope that we could essentially pacify the country, and that might work for a little while. And two decades later, we run away just like we did in Vietnam and Iraq.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So Russia should have learned from us, but they didn't. Do you think we can still learn from our past mistakes sufficiently to help get Russia out of Ukraine?

GIDEON ROSE The main lesson of these cases for what we do in Ukraine now is to realize that we're on the opposite side from what we usually are doing. Usually, the United States is the strong, dominant alpha power. We're the conqueror. We're driving things. In this case, Russia is in the Washington role that has two big implications. First, for our own strategy, we're trying to get the Russians to voluntarily walk away like we did. So we need to basically confront them with a hurting stalemate or defeat on the ground and use whatever tactics hurt us. Lots of IEDs knocking off collaborators in the areas, making it impossible for Russia to achieve its goals.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But Gideon, we're not there. I mean, we're not putting IEDs in the road.

GIDEON ROSE We are Pakistan. When the United States is in Afghanistan, we are Iran. When the United States is in Iraq, we are providing help across the border to the locals. We are the Ho Chi Minh Trail, supplying weapons to the people inside Vietnam, fighting the great power. And so we need to think like the people who beat us in those wars because Russia and Putin right now is in a situation pretty similar to where the United States leadership was in Vietnam from the late 1960s and where we were in Iraq and Afghanistan from the mid-aughts, which is now Putin realizes the mistakes he's made. Now he realizes that he's paying a huge price and you could already see him start to backtrack. But it's very difficult psychologically to go through the Kubler-Ross five stages of grief denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. We're trying to get Putin to recognize in weeks what it took us decades to accept. And humiliating him is actually probably a bad way of doing that. We actually want to give him something of an exit route so that he can be like Nixon and Kissinger thinking of having maybe a decent interval or a way out. He's concerned this time about his loss of credibility. All these things, we felt ourselves. And it's why we stayed in Vietnam so long. It's why we stayed in Iraq and Afghanistan so long because we feared the consequences of leaving. We want to make leaving as attractive as possible, so he'll choose that option rather than continuing to pound Ukraine.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You mentioned psychology and you've observed that in 1972, Nixon and Kissinger bombed the hell out of North Vietnam shortly before pulling out. A big macho display that we could spin to seem like a victory?

GIDEON ROSE The United States negotiated an exit from Vietnam in the fall of '73. But when we publicized it, our client in South Vietnam said, Wait a second, I don't want this settlement because I'm ultimately going to fall because of it. When he made his objections public, Nixon and Kissinger came up with the idea of the Christmas bombing in late 1972, early 1973 to make it seem like we were bombing the North to get them to concede even more and create a better settlement when in fact it was essentially covering up that we were forcing Thieu to sign the settlement we wanted. And here this is the kind of case in which everyone talks about how Putin controls the Russian information environment, and he's suppressed the press. It's awful for a variety of reasons, but it's actually pretty good for war termination because the more Russia and Putin can control the domestic narrative of whatever happens, it almost doesn't matter whether they have a real victory as long as they can sell it to their own public that way. That means Putin can declare something and get it believed.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Is there any way that the U.S. can thread that needle with Zelenskiy and Putin and appearing like victory in Ukraine and in Russia? And I mean, I just don't know how you come up with a story like that.

GIDEON ROSE So the way you do it is by not rubbing their nose in it. The way the United States can help is by not doing things like what Biden did at the end of his speech in his ad lib the other day.

[CLIP]

PRESIDENT BIDEN Will never be a victory for Russia. For free people refused to live in a world of hopelessness and darkness. We will have a different future, a brighter future rooted in democracy and principle hope in light. Of decency and dignity of freedom and possibilities. For God's sake, this man cannot remain in power. [END CLIP]

GIDEON ROSE What you want to do now is allow the Russians to slink away quietly and climb down from where they are. And the more you get carried away and make this a giant anti-Russian crusade, the more it makes it harder for him to back down. Think of human psychology on a basic level. You meet anybody. If we know we have to do something, then nagging and yelling at us to do it makes us more reluctant, not more willing to do it. And so by getting out of the way and lowering the temperature, even as you fight the war, you make it easier for Putin to accept what he ultimately has to accept. We want them to do what we did in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. Which is walk away with their tails between their legs.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Right. But he's going to have to come up with the story.

GIDEON ROSE This is the thing we have to understand. So what we want to do is basically say "not, he's an evil authoritarian who's psychotic and has to be assassinated." Let's just say he's a leader who got into a bad situation and is now trying to reverse course and preserve what he has left at home.

BROOKE GLADSTONE We're not going to publicly say that stuff.

GIDEON ROSE No, you don't say that stuff. But if you think that way, it'll affect what else you say. If you think that way, you will try to smooth the way out rather than make it harder for him to climb down.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Talk about lessons learned and outdated narratives ripe for burial. What can we learn? Rather, what will we learn from Russia reenacting some of our most tragic mistakes? Is it clearer when someone else is acting as stupid as we have?

GIDEON ROSE Hypocrisy is nearly universal in human psychology and in international relations as well. We are seeing all the downsides of the attacking, conquering power and a colonial war in Ukraine, and we're reacting viscerally against it. When we were in the position of the Russians trying to conquer other countries that didn't want to be conquered, we convinced ourselves that those downsides either didn't exist or were justified by the ends or weren't even happening because we couldn't do something like that. And this should lead us to look in the mirror and realize that the psychological and emotional and strategic mistakes the Russians have made are not unique, but fairly common mistakes that we have made in the past and will be prone to make ourselves in the future unless we guard against them by being self-aware, seeing ourselves as others see us, not just as we wish to see ourselves.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Gideon, thank you very much.

GIDEON ROSE Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Gideon Rose is a fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy at the Council on Foreign Relations and is the author of How Wars End: Why We Always Fight the Last Battle. His piece in Foreign Affairs is titled The Irony of Ukraine: We have met the Enemy and It Is Us. Coming up, the real knowns and the known unknowns about the possibility of nuclear war with Russia. This is On the Media.

[BREAK].

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. Since the start of the conflict in Ukraine, talk of Russian nukes has loomed over the coverage.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT As Russia's tanks rolled into Ukraine. Vladimir Putin made a threat not heard since the height of the Cold War.

PUTIN TRANSLATOR Russia's response will be immediate and will lead you to such consequences never experienced in your history.

NEWS REPORT Then days later, he raised the alert level of the world's largest nuclear arsenal. Only President Putin knows how far he would really go. In the meantime, it's a gamble that the West can't afford to take. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The New York Times this week reported about new spending priorities in Europe in response to the war. In it, the recently elected Romanian prime minister, a former battlefield general, expressed shock at how much the new world resembled the old. We never thought we'd need to go back and consider a potassium iodide again, he said. And yet Romania will be spending millions for those pills to help block radiation poisoning should a nuke go off. But just how likely is the threat of nuclear war? Taking a closer look at Russia's nuclear weapons systems might temper some of those anxious narratives. Kristin ven Bruusgaard studies Russian nuclear strategy as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oslo. Welcome to the show, Kristin.

KRISTIN ven BRUUSGAARD Thank you very much. Glad to be here!

BROOKE GLADSTONE MIkhail Zygar, who's the author of All the Kremlin's Men., described the quote "Collective Putin," that is to say the echo chamber of Yes Men submissivly validating Putin's ideas to the point where now he has really and truly come to believe that only he can save Russia. But is there any suggestion that this monolithic decision making is happening with regards to nukes?

KRISTIN ven BRUUSGAARD We do believe the Russian president alone cannot make a decision and issue an order to launch a nuclear weapon. We believe that there are three so-called nuclear suitcases in Russia where one is with the president, but two others are with the defense minister and the chief of the General Staff.

BROOKE GLADSTONE How does that compare to how it works in the U.S.?

KRISTIN ven BRUUSGAARD The difference is that the decision in the American system lies with the president alone, and the decision in the Russian system lies with the president in consultation with either the defense minister or the chief of the General Staff.

BROOKE GLADSTONE We know there has been tension with the defense minister.

KRISTIN ven BRUUSGAARD Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu filled different positions within the Russian government for almost two decades. In recent days and weeks, there has been speculation about this relationship between Minister Shoigu and President Putin. He has not been seen in public for some time in connection with the relatively abysmal performance of the Russian military in Ukraine.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And then we have the chief of the General Staff. I haven't heard much about how he stands. Putin only needs him. He doesn't need Shoigu,

KRISTIN ven BRUUSGAARD Chief of the General Staff. Gerasimov is a military professional and has executed a number of military operations, including the military operation into Ukraine in 2014 and the annexation of Crimea and operations in Syria as well. But General Gerasimov and Shoigu as well. We don't know their personal preferences when it comes to nuclear weapons. We do, however, have some insights into the debates that have been going on within the General Staff. Russian military theorists traditionally talk about different types of wars and the typify these wars, according to their scale and scope and intensity. And the type of war that we are seeing in Ukraine is one that Russian military planners would probably denote a local war that is a limited war with a limited number of actors or states. And where the warring action takes place on the territory of those states. Nuclear weapons would not play a significant role in this type of war.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Let's talk about some of the actions that caused a tremendous amount of anxiety in the West, including a few days after Russia invaded Putin, ordering his military leaders to put Russian nuclear deterrent forces on a quote special regime of combat duty. This was reported in some papers as Putin threatening escalation of nuclear war by putting his weapons on alert. Officials in the US didn't know exactly what it meant. What did it mean?

KRISTIN ven BRUUSGAARD Russian officials actually came out afterwards to clarify this, perhaps in response to the Western confusion regarding what this meant and said this means that we have increased the level of manning in the military units that contain strategic, long range nuclear forces that can reach targets, for example, in the United States. This was a signal to the West not to interfere. It was not a signal that Russia was considering using nuclear weapons. Because the Russians know that that would be a suicidal act.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Nevertheless, a perception of a nuclear trigger happy Putin isn't entirely speculative. Some of it comes directly from his own rhetoric on nuclear weapons. Right?

KRISTIN ven BRUUSGAARD There is significant reason for this speculation, in part because of the way that the military operation in Ukraine is evolving. The Russian leadership could turn increasingly desperate so as to reach to either nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction. I mean, the potential for Russian chemical weapons use or even biological weapons use. There has also been the speculation about Putin's isolation, his rationality, the degree to which he's able to assess the costs and benefits of a certain action.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Based on what the spectacles of his cabinet meetings?

KRISTIN ven BRUUSGAARD Spectacles of his cabinet meetings. Also, the initial decision to launch this large invasion into Ukraine. I mean, that seemed like a totally irrational action that could not in any way produce the outcome that he seems to be interested in. But having said that, I think it's important to remember that there is a difference between a nuclear signaling and actual nuclear employment in the conflict in Ukraine. In the event that this war becomes a direct confrontation between Russia and NATO, I think that the potential or the likelihood for nuclear employment from the Russian side may increase dramatically. But then we are talking about an outright war between NATO and Russia and where NATO's in fact attacks targets on Russian territory. So this is a very different situation from the situation we have today.

BROOKE GLADSTONE On Russian territory. See, this is a big question for me. NATO and the West in general see a no fly zone, which would involve attacking and shooting down Russian aircraft as crossing a potential red line. We don't know, though, what that red line is and whether it will stay where it is.

KRISTIN ven BRUUSGAARD The Russian leadership has talked about this no fly zone as a potential red line as well to warn the West against directly becoming involved in this conflict. But I think that that red line basically pertains to a direct confrontation between NATO's and Russia actually materializing. That is not to say that a direct confrontation between NATO's and Russia would immediately produce nuclear escalation. But the point is that at the moment that you have a direct confrontation, both sides may start considering taking actions to destroy or inhibit the military capabilities of the other side. For example, NATO's strikes on Russian territory or Russian strikes on NATO's territory. Then you have basically an outright war between NATO's and Russia. And this is the type of situation where Russia starts talking about a threat to the very existence of its state. And in those circumstances, they would consider responding with a nuclear weapon.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You've described what would trigger a nuclear attack, but we haven't entirely taken in his state of mind: the isolation. Recently declassified reports that suggest he's not being told the truth about how the war is going, about the impact of economic sanctions by his own staff. Is it possible he could make a decision that is utterly irrational?

KRISTIN ven BRUUSGAARD The Russian president has had a tendency to brandish nuclear weapons to a much greater extent than his Western counterparts. But he, too understands that crossing this threshold breaking this taboo would give him a historical legacy that he perhaps would not want. There is much speculation about how he's very preoccupied with his own historical legacy, how this may maybe one motivating factor for this invasion. So this is at least one potential consolation.

BROOKE GLADSTONE I'm just wondering how can media outlets more accurately report what's going on? You've observed that in many ways, Western media is just like Russian media. May be prone to a more sensationalistic approach to reporting on these issues than is warranted.

KRISTIN ven BRUUSGAARD One example of this is this interview with Putin's press spokesman, where he was pushed very hard by an American journalist, whether he could rule out the potential of nuclear weapons use, and he hesitated and responded that Russia would use nuclear weapons only if the existence of the state was under threat. So basically, his response was just reaffirming what has been longstanding Russian doctrine and policy. But because of the current context that produces, you know, headlines about how Russia refuses to reject the scenario of nuclear weapons use, when you know, another headline to that story could just be that Russia reaffirms its long standing nuclear policy.

BROOKE GLADSTONE As someone who thinks about nuclear strategy for a living. How do you navigate the existential fear of nuclear war?

KRISTIN ven BRUUSGAARD You know, you almost have some kind of technical approach to several of these existential issues. But then of course, at times and sometimes even regularly, you stop and you start considering the repercussions and implications. And you know you you get gripped by an existential fear that is warranted when you talk about a potential nuclear armageddon. You can find some consolation in the notion that the states that do have nuclear weapons as far as I can understand, most nuclear weapons states have those weapons precisely in order not ever to have to use them.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Kristen, thank you very much.

KRISTIN ven BRUUSGAARD Thank you so much for having me.

Kirstin ven Bruusgaard wrote Understanding Putin's Nuclear Decision Making for the security blog War on the Rocks. Coming up the emotional arc of nuclear fears. This is On the Media.

[BREAK]

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. A new poll this week from the A.P. and NORC Center for Public Affairs Research found that when asked, close to half of Americans say they are very concerned that Russia would directly target the U.S. with nuclear weapons, 30 percent more were at least somewhat concerned. Now with nuclear historian Alex Wellerstein. We take on the whole history of those fears, starting with the very birth of the bomb.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN Even in 1945, as excited as they are by the end of World War Two. People are immediately thinking about what would another World War look like in the future? Who is the most likely country to get nuclear weapons after the United States? And most Americans think it's going to be Russia – in the right. So in September 1949, the United States detects the first Soviet nuclear weapons test in what is now Kazakhstan, and the United States decides to build the hydrogen bomb, which is thousands of times larger than what the atomic bombs had been. So they sort of go all in on bigger bombs. But that also creates bigger fears because you know that at some point the other guy's going to get that weapon as well. You also have the discovery in early 1950 that there were lots of Soviet spies in the American bomb project during World War Two. And so this leads in the McCarthyism, right? You have a lot of stuff going on. So by the end of the 1950s, the United States is, to some degree, directly vulnerable. That's a much more personalized kind of fear.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It's also when one of the earliest H-bomb prototypes caused terrible radiological accident called Castle Bravo.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN Right. So Castle Bravo was in March of 1954. This was essentially the second H-bomb ever tested. It was the first H-bomb that you could actually drop out of a plane.

BROOKE GLADSTONE We were testing it

ALEX WELLERSTEIN The United States tested it in the Marshall Islands and the Pacific Ocean. The Hiroshima bomb, just to put it in numbers, was 15000 tons of TNT, 15 kilotons. The castle Bravo was 15 million tons of TNT.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Oh god.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN And it created this huge plume of downwind radioactive contamination that ended up going over inhabited areas in the islands that had to be evacuated, going over areas of ocean where there was a Japanese fishing boat. This Japanese fishing boat went back to Japan. One of the sailors died on it. As a result, they radioactive fish got reintroduced into the Japanese fishing market, the Japanese boycotted fish for several months. You could see that this spirals in a really big way and makes it really clear that if you had a castle Bravo style weapon, go off in Washington, D.C., the radiation, if the wind was blowing the right way could make all of the northeastern seaboard uninhabitable. This is also what causes the movie Godzilla to be made. All of those 50s movies about mutated insects and animals come out after this period, so it's not even just what the target of the weapon, it's what's downwind of it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And the early 60s, obviously the Cuban Missile Crisis,

ALEX WELLERSTEIN Cuban Missile Crisis, as close as we ever get to full scale nuclear war. And this was for real. This really could happen. And not only could happen because people want it to happen sometimes, but it could happen almost accidentally.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You're talking about Dr. Strangelove and Fail-Safe.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN This sort of stuff comes out of that, but that kind of stuff almost happens during the actual Cuban missile crisis. There are mishaps, false alarms that are accidents.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Could you describe one of the accidents?

ALEX WELLERSTEIN There was a Russian submarine off the coast of Cuba and there was an American destroyer above it. The destroyer trying to get the submarine to surface by setting off depth charges high enough up that it wouldn't destroy the submarine, but a way to say you better come up to the surface. We've got you cornered. The submarine thought they were trying to destroy them. They had nuclear tipped torpedoes. 2 out of the 3 officers on the submarine voted to use the torpedo. A third officer vetoed it. And if that third officer hadn't been there or went the other way, they would have retaliated with nuclear weapons. And who knows where that goes from there? I'll give you one more great example of what could go wrong. At an American missile base in northwest part of the United States, right? A soldier guard there thought he saw a Soviet agent trying to break into the base. It turned out to be a bear.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

BROOKE GLADSTONE But this can happen, right? This is during the Cuban Missile Crisis. He goes and sets off the perimeter alarm. The somebody is trying to break into the base alarm, but the wiring turned out to be incorrectly done. And so it sets off the we're being bombed alarm. And so they scramble jets with nuclear armed weapons – what are the odds, right? In the middle of a crisis, and yet these things still happen.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And if you look at the Cuban Missile Crisis itself, now that we can hear the tapes, we know that there was a huge rush to escalation and only one man in the room. One man was opposed to it, and that was President Kennedy.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN It's actually even more horrifying now that we have more information about the Soviet side of this. So, for example, one of the biggest pushes during the Cuban missile crisis from people like Curtis LeMay, he was the head of Strategic Air Command. LeMay was saying, "we should just invade the island. They don't have nukes there now. We'll just take it over. That'll be that." We now know that they actually had nukes on the island. Hundreds of nuclear weapons, including tactical nuclear weapons, which would have been used to repel an invasion. And amazingly, the Americans just didn't know that. I got a chance to ask the CIA photo interpreter, who was the one who gave this intelligence and said there are no nukes on the island yet. And I said to him, "How did you get this wrong?" And he said, "Well, the way we do it is we look at pictures from what a nuclear bunker looks like in the Soviet Union, and we know that those ones have nukes in them when they have fences and guards around them. And we saw they had bunkers in Cuba, but they didn't have fences and guards around them, so we figured they must be empty." And it turned out they weren't.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Then a lull in the mid to late 60s, even though weapons are being stockpiled.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN You have this period that we call detente. The U.S. and the Soviet Union get a little chummier. The U.S. and China get chummier. At the same time, there's many more weapons being built. They're getting more sophisticated, but public attention to the weapons is generally lower. Some of that is because the nuclear testing that had been going on, is now underground. And so you move on to other things, and to be sure, the 60s were a turbulent decade, even without thinking about nuclear weapon, which this is somewhat relevant to our present time. It's not like when nuclear anxieties are low. Everybody's sitting around and saying, what a great world we live in. We're concentrating on other things a lot of the time. Civil rights movement, for example, getting a lot more attention at this time period than the nuclear arms race. But by the late 70s, the Soviet stockpiles had gotten quite large. So you start to see a ramping up of nuclear concerns, putting more missiles in Western Europe, debates over whether you should make new types of weapons like the neutron bomb. And Reagan comes to power on the argument of We've fallen behind the Soviets, these evil empires, they can't be worked with. That works for him in terms of elections, but it also drives the fears way, way, way, way up.

BROOKE GLADSTONE In 1983, there was the Soviet nuclear false alarm incident.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN Other than the Cuban Missile Crisis, I think most scholars would put 83 is the closest we came to some sort of nuclear war, which I don't think most people realize. But the war scare of 83 is a lot of things. So one of them is a Soviet false alarm when the Soviet early warning system says there's missiles in coming. The person manning this computer station, Stanislav Petrov, he basically says, "I don't think this is real and it doesn't pass it up the chain of command,".

BROOKE GLADSTONE Which is treason!

ALEX WELLERSTEIN Well, the American systems had false alarms also, during this time period. Some point in the '70s, I found a note from Kissinger that said that they were having one false alarm a week at one point. It's unbelievable, right. So the Soviet systems are probably not better made than ours. And so people did use their judgment. But yeah, in 1983, the Soviets are very worried that the United States could attack them first. And so not passing it up the chain is him really putting a lot on the line. Either it's a false alarm or they're all going to be dead. Is it really his job to make that choice? It's not clear. So other things that are going on in '83. The United States is doing things that are deliberately provocative, like routinely entering Soviet airspace with military planes to see what their response would be. How quick could they get defenses up and running? How quick do they ping them on the radar? So any plane that was going to come in, they were going to think it was an American plane and go after it. And this is what led to them shooting down Korean airliner 007 in 1983. Which was a horrible accident, but they thought it was one of these American planes that was trying to probe them and mess with them.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Wow. When it comes to what the public feels, you said in the AP piece that it's difficult to measure the public's degree of fear over time because polls use different methodologies or pose questions in different ways.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN I'm relying here on a lot of insight I've got from one of my colleagues who a political psychologist named Kirsten Carl. Are you really getting a representative sample? Are you talking to enough people? And then the way you pose, the question matters. So if I give you a question where I say, how worried are you about Russia using nuclear weapons? Are you a little worried? Very worried. I worry. Every day you'll be thinking about, Oh, how do I feel about this? That's different than if I go to you and say, What are you worried about? You might say, I don't know. Climate change, inflation, crime, the subway, whatever. This is one of the tricky things. If you ask people today about nuclear weapons in a structured way, they'll often give you a response that it's on their list of things. But if you ask them in an unstructured way, if you just say, what are you worried about, that typically doesn't come up as much, which I just as a contrast. In 1983, they did an unstructured poll where they basically asked people, What are you worried about? In 1983, 25 percent of Americans were worried about nuclear war, and they didn't need to be prompt about it, so that's a pretty good indication of one out of four people rank it higher than crime, the economy, whatever. That's a really high level of anxiety.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You created Nuke Map, which is a website that shows how much destruction different types of nuclear bombs could cause in any city in the world. The site has seen like 20 times its normal traffic in the past month. Why did you create it?

ALEX WELLERSTEIN So I made Nuke Map 10 years ago, and I made it because it's really hard to wrap your head around nuclear weapons. We've all seen the movies where the nuke goes off and the screen fades to white, and that's sort of the end of the movie, right? And a lot of people, that's sort of how they envision a nuclear weapon. Oh, it would just kill everything all at once; the end. And one thing there's a lot of different types of nuclear weapons, right? There's a real big difference between the weapon dropped on Hiroshima. The weapons made in the 1950s and the weapons used today. So Nuke Map is a web site that I made because being able to see that kind of damage superimposed on places I know makes a big difference. To get back to this conversation about fears, I think there's a really big difference between a sort of abstract, impersonal fear and a much more personalized customer fear. So if your idea of nuclear bomb going off as the screen fades to white, the movie says the end and the credits start rolling. You end up not taking that seriously as something that's likely to happen. You put that in the part of your brain, you put your awareness of your own inevitable death. An actual nuclear weapon going off would not destroy everything. If a Hiroshima sized bomb, again not a big bomb, went off in Manhattan, you're talking about 400,000 people dead, 400,000 people as an unimaginable amount of dead people. But it's also not that many out of the people who live in the Greater New York metro area, you'd still have a lot of survivors, and in some ways that's worse. You don't necessarily see yourself as being instantly dead in that situation. You see yourself as one of the people who might have to clean up the mess and deal with the grief. It's actually more powerful to show people that these weapons are massively powerful, but not infinitely powerful in some ways, and we've done research that backs this up. This causes people to take them more seriously as a human problem and not just part of the universe you can't deal with.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Alex, thank you very much.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN Well, thank you so much. I really enjoyed being here.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Alex Wellerstein is a historian of science and teaches at the Stevens Institute of Technology. In January of 2018, residents of Hawaii received a text alert that read Ballistic missile threat inbound to Hawaii seek immediate shelter. This is not a drill. The panic lasted for 38 minutes before the message was revoked. Turns out it was another false alarm. A spokesman from the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency said Quote "Someone clicked the wrong thing on the computer." A few weeks after the incident, I spoke to Marsha Gordon, director of film studies at North Carolina State University, in response to the Hawaiian incident. She'd written a piece about the made for TV movie: The Day After about the after effects of a nuclear strike on the U.S., which aired in November of 1983. 1983, remember was the year, Alex Wellerstein said we came the closest to nuclear war since the Cuban Missile Crisis. 100 million Americans nearly half the country tuned in. After the broadcast, newsman Ted Koppel hosted an all star panel of scientists, pundits and politicians all talking about disarmament and deterrence.

[CLIP]

TED KOPPEL If you can take a quick look out the window, it's all still there. Your neighborhood is still there, so is Kansas City and Lawrence and Chicago and Moscow and San Diego and Vladivostok. What we have all just seen is sort of a nuclear version of Charles Dickens Christmas Carol. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The Day After and managed to catalyze a national conversation about American nuclear policy. But that didn't make it a good movie.

[CLIP]

NICHOLAS MEYER And more than that, it was not intended to be a very good movie. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The director, Nicholas Meyer, was interviewed on the Outline World Dispatch podcast in 2017.

[CLIP]

NICHOLAS MEYER It has to be like a public service announcement. If you have a nuclear war, this is more or less what it's going to be like. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE Back then, Marsha Gordon was in junior high. She well remembers the fear and the fervor.

MARSHA GORDON There's basically a before and then the day after. And so you have normal Midwestern people getting married, people having babies, people going about their lives.

[CLIP]

CHEERFUL WOMAN Hellooooo!

MISS DOVER Where have you two been? Come on.

APOLOGETIC MAN Sorry, Miss Dover. [END CLIP]

MARSHA GORDON And then all of a sudden, this scenario unfurls...

[CLIP]

ALEX WELLERSTEIN He hit one of our ships in the Persian Gulf.

[PEOPLE PANICKING IN THE BACKGROUND]

WELL-INFORMED MAN The Russians, what do you think? [END CLIP]

MARSHA GORDON And people are panicked as the alarm goes out that there's incoming nuclear missiles.

[CLIP]

COMMANDING OFFICER Roger copy. This is not an exercise,.

OFFICER Roger. Understand Major Reinhart. We have a massive attack against the U.S. at this time. ICBMs. [END CLIP]

MARSHA GORDON And then we are deploying them as well. And so everyone located near these missile silos is watching them come out of the ground. The most haunting images in the film are seeing these missiles going up into the air and people looking at them.

[BLASTING SOUNDS]

MARSHA GORDON ABC decided not to run advertisements after the blast. It just played through.

[CLIP]

DOCTOR Now what about fuel to boil water? Heat food, sterilize surgical instruments?

OFFICIAL What about bringing in wood?

SCIENTIST You can't burn wood, it's been contaminated. Just put radiation right back in the air. What about bottle gas?

SUPPLIER There's some butane, but no more than about three days worth. [END CLIP]

MARSHA GORDON It is the farmers, the doctors, the people on the ground have the sense and have the ability to navigate this crisis in a way that the government does not.

[CLIP]

FARMER Can you explain what you mean by scraping off the top layers of my topsoil?

OFFICIAL Exactly that, Jim. You just take the top four or five inches of your topsoil.

FARMER And do what with it? We're talking 150, maybe 200 acres, a man in here. Being big is one thing, being realistic is another. Suppose you find a hole where you can drop all this dead dirt. What kind of topsoil is that going to leave you for raising anything? Where did you get all this information, John? All this good advice? Out of some government pamphlet? [END CLIP]

MARSHA GORDON And there is even a presidential broadcast over the shortwave radio.

[CLIP]

PRESIDENT There has been no surrender, no retreat from the principles of liberty and democracy for which the free world looks to us for leadership. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE We see people stumbling through the rubble as he's talking, and some who are huddled over the radio have this reaction.

[CLIP]

NERVOUS MAN That's It? It's all he's going to say?

OPTIMISTIC MAN Hey, maybe we're going to be OK. What do you want to hear?

NERVOUS MAN I want to know who started it, who fired first, who preempted.

CYNICAL MAN You're never going to know that.

PRACTICAL WOMAN What difference does it make?

[OVERTALK]

OPTIMISTIC MAN …doesn't want anyone to think we lost the war.

PRACTICAL WOMAN You believe that? [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE After the broadcast, there was a panel hosted by Ted Koppel. It had the great astronomer Carl Sagan and Elie Wiesel known for his writings about the Holocaust and hunting Nazis. George Shultz from Reagan's defense team.

MARSHA GORDON It's a discussion of contemporary America's nuclear strategy and also of the Soviet Union, and some of the questions from the audience point to where we are today.

[ CLIP]

WORRIED AUDIENCE MEMBER What are we to do 20 to 25 years from now, when the superpowers no longer have the decision making power about whether nuclear war will or will not occur? What about the Khomeini or Gadhafi having that capability [END CLIP]

MARSHA GORDON and actually over and over again, Wiesel says things that are very powerful and very timely.

[CLIP]

ELIE WIESEL I'm afraid of madness. I'm afraid that madness is possible in history. And the only way I believe to prevent that madness would be to remember. If we remember that things are possible, then I believe memory can become the shield. [END CLIP]

MARSHA GORDON We live in a world currently where I think that idea really resonates.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And yet, the New York Times ran a story before the broadcast, quoting a therapist urging families not to watch the post-show panel discussion hosted by Ted Koppel. Quote It's extremely important for people to talk about the day after themselves and not let television do the talking and feeling for them. If they do that, they'll lock feelings of despair and fatalism inside themselves.

MARSHA GORDON Well, I have read a number of articles that came out just before this airing, in which psychologists expressed actual long term concerns about young people watching this program that ranged from bedwetting and nail-biting to insomnia. A lot of people did not think that people under the age of 12, for example, should maybe watch this at all.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And they were viewing guides, to guide conversation. Here's a sample question: of all the institutions which presently constitute American society. Which ones would be best suited to handle a postwar society and its manifold problems?

MARSHA GORDON Yeah, so the ABC apparently produced around half a million of these study guides and distributed them to schools and churches and community centers. Clearly, they were trying to promote viewership. It was also, I think, to forestall criticism that they were just putting this terrifying movie out in the world and letting people fend for themselves with how to deal with it. The study guide does, though, ask some really good questions about how people thought about the likelihood of this happening, about its survivability. The political context and consequences which was certainly on everyone's mind. There were protests immediately after this viewing, and of course, there were many people who were anti-nuke and wanted to go into a period of incredible disarmament.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Interestingly, one person who seems to have gotten that message was Ronald Reagan. Not long after the film, Reagan held a series of summits with Mikhail Gorbachev. about both countries, nuclear arsenals.

MARSHA GORDON Well, if you listen to that viewpoint discussion after the airing of the day after. This is discussed, including by Secretary of State Schultz, that the goal was not just to proliferate, that the goal was to get to a point where both countries would agree to start dialing back their nuclear storehouses. And Carl Sagan talks about this idea that you imagine two people in a room.

[CLIP]

CARL SAGAN A room awash in gasoline. And there are two implacable enemies. One of them has 9000 matches. The other has 7000 matches. Each of them is concerned about who's ahead. Who's stronger? Well, that's the kind of situation we are actually in. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE You know, we posted your piece on our On the Media Facebook page, and a listener. Wayne in Hawaii, wrote that he's in his 40s, and he saw the film as a child and quote "A few weeks ago when the false missile alert went off in Hawaii. I distinctly remember thinking, Well, it finally happened. It wasn't panic. It wasn't fear. It was more resignation than anything else. I think because we were the last generation that grew up during the Cold War, nuclear annihilation was always a possibility, and it permeated the culture, especially with depictions like The Day After. That anxiety was always there and it never left us.

MARSHA GORDON Wayne is absolutely right. I don't think that people who are in their thirties and younger have a sense of the fear. There's a big difference between hearing rhetoric and imagining what this would look like.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So how would you remake it today?

MARSHA GORDON I would definitely think about a kind of global context that was not just focused on American soil, but on the many places in which this attack would likely transpire, and the question of the technological meltdown is incredibly relevant and maybe the most relevant in an odd way, especially if you want it to resonate with young people.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You mean their iPhones won't work anymore.

MARSHA GORDON Yes. If you've never read a map, if you've never figured out how to do anything without consulting technology, how are you going to navigate a world in which technology is no longer functional? And so who is going to have that wisdom? And it's going to be older people who know how to get a shortwave radio to work. Know how to get from point A to point B by looking at a map, for example. You could also begin to imagine a scenario in which class gets turned on its head a little bit. I mean, who knows how to weld? Who knows how to hunt? Is it someone in Silicon Valley who's made their millions off of technology? Or is it somebody who has been having to work in a kind of blue collar job? You know, when I've kind of rolled this over in my mind, the fact that the day after takes place in such an immediate time post-blast, I think it would be very interesting to think of a kind of longer game like the year after.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Mmhmm. And then 7 years after and then 75 years after?

MARSHA GORDON Yeah, right. I mean, what are the long term consequences? I mean, the idea of a nuclear winter is not approached at all in The Day After, but what if it was never warm enough to germinate a seed? How are you going to survive?

BROOKE GLADSTONE Thank you very much.

MARSHA GORDON You are very welcome.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Marsha Gordon is a professor and director of film studies at North Carolina State University. We first aired this interview in 2018.

And that's the show! On the Media is produced by Micah Loewinger, Eloise Blondiau, Rebecca Clark-Callender and Max Bolton with help from Aki Camargo. Our Technical Director is Jennifer Munson, our engineers this week were Andrew Nerviano and Adriene Lily. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media, is a production of WNYC Studios. I'm Brooke Gladstone.