Reading the Room

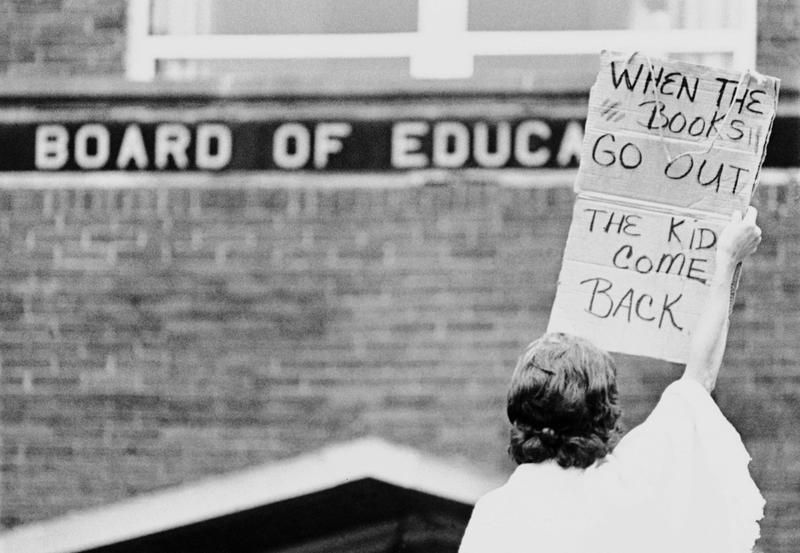

( Associated Press / AP Photo )

KELLY JENSEN It's not about the kids, it's about creating such havoc in public schools that they're able to say, why are we paying tax money to this institution that isn't doing its job?

BROOKE GLADSTONE The cries to pull books from school libraries and curricula are for... who exactly? From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. Meet the parents!

[CLIP]

PARENTS Parents have lost their voice to represent themselves and their children. So we're bringing our own chairs to the table, right? And we're going to reclaim those things. [END CLIP]

JENNIFER BERKSHIRE The pandemic has been brutal on disruptions to childcare, and so politicians find electoral gold in the parents rights cause.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Plus, the student who took his book Banning School Board all the way to the Supreme Court.

STEVEN PICO It's almost meant to be. I was born to be the plaintiff in this case.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It's all coming up after this.

[END OF BILLBOARD]

BROOKE GLADSTONE From WNYC in New York. This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. This summer, Utah's largest school district removed over 50 books from school libraries. Pan America reports that over 20 of the freshly illicit titles feature LGBT characters or themes.

[CLIP]

UTAH SCHOOL DISTRICT The titles that were reviewed were found by this committee to contain sensitive material, and they do not have literary merit. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The allegedly meritless books include Jodi Picoult, whose number one New York Times bestseller, 19 Minutes, about a school shooting, a Judy Blume title and a memoir called Genderqueer. The removal of the books is temporary until the school board formalizes its policy for book removals. It was made possible by a bill that passed earlier this year in Utah, part of a new wave of legislation limiting school curricula.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT In Virginia schools they're now required to alert parents if any books assigned to the curriculum have sexually explicit content. They're required to have law enforcement liaisons for those schools.

NEWS REPORT In Florida, the parental rights and education law, the one that critics call "don't say gay," bans instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity in classrooms. Another education law is the Stop Woke Act. This one restricts how race related topics are taught in school and also workplace training.

NEWS REPORT In October. Republican state legislator Matt Krauss requested every school district in the state, scour their libraries for a list of 850 books. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The American Library Association reports that last year saw more than 1500 book removals and challenges – a new record. And there is a reason the ALA didn't use the word "ban." The association prefers the term "book challenge" to more accurately reference these cases, which vary in scope. For example, a book removed from a class's required reading might still be available in the school's library, or a book allowed in one district might be absent from a neighboring one or even from that neighborhood's public library. In fact, over 40% of these challenges occurred in public libraries in 2020. Earlier this year, I spoke to Kelly Jensen, a Chicago based editor at Book Riot, who writes a weekly update on book censorship news in the U.S. She says this nascent battle over books in schools straddles the nation.

KELLY JENSEN The reality is it's happening everywhere. It's happening in the Chicago suburbs. It's happening in New York state. Outside Seattle-Tacoma in one of the suburbs, a middle school librarian was trying to add more LGBTQ positive books into the collection. Doing what a librarian does researching these titles, making sure they have great reviews, and that they would be appropriate for their community. The principal bypassed all of their policies and procedures, just quietly pulling these titles from shelves. People in that area were shocked it was happening in their backyard.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Let me unpack a couple of things here. First, what was going on in the principal's mind? Was it simply to avoid a really noisy school board meeting in the future?

KELLY JENSEN There's been a number of groups in that suburban area that are working toward challenging materials. Toward oversight in curriculum. And so, my read was that the principal was trying to make sure that nothing like that would happen.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And parents who wouldn't object to the books – who might actually welcome the books. They don't know that that's going on.

KELLY JENSEN And it's not just parents who don't know, it's the students don't know. The teachers don't know. It takes somebody who is willing to blow the whistle like this particular librarian was to get this quiet or soft censorship even noticed.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Moms for Liberty. You've drawn attention to this nonprofit group. You say it has 165 chapters and 33 states. You also say they operate county by county rather than city or state. Meaning that the action can be very quick and targeted.

KELLY JENSEN Moms for Liberty created a campaign that they are calling moms for libraries. They have collaborated with a publisher called Brave Books and Brave Books, publishes titles that are conservative that are quote unquote 'liberty focused' and that have a religious theme. They're doing two things: they're pulling books out of the library, which is giving them negative press. But if they create a campaign called Moms for Libraries and donate books back to libraries, that certainly gives them a different look in the public eye. But when you start to dig in a little bit, you realize that this particular publisher they're working with is propaganda, so they're pushing their agenda in two directions.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Of course, the word agenda gets tossed around a lot. The people who would challenge books say that it's the gay agenda or the trans agenda or the liberal agenda, or the critical race theory agenda that is going to twist the tender minds of our youths. So let's talk about what books are most prone to censorship.

KELLY JENSEN One of the big ones is Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe, and it's a book about a gender queer person coming to understand their gender identity. One of the tactics being used by these groups and individuals is looking into state policies around topics like obscenity and pornography and using that state law or statute as a proof of why these books shouldn't be in schools or libraries.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So these books, do they have to meet the standard of having no redeeming social importance? Or is it just a threat? Do they actually prevail on legal grounds?

KELLY JENSEN In some states, they're trying to create the legislation that would make them be removed, where in other places who is on the board of the school or library has the power to make that decision, rather than any actual prevailing legislation.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Obviously, books that address gender identity have come under the withering light of Moms for Liberty. Books like All Boys Aren't Blue, Gender Queer and the ever-popular Heather Has Two Mommies. Also, books written by black authors and featuring black characters from The Bluest Eye, a standalone story by Toni Morrison – To Kill a Mockingbird by the most emphatically, not black. Harper Lee.

KELLY JENSEN I also want to add to this list. Dear Martin by Nick Stone. That's currently coming under fire, and I bring that one up in context of To Kill a Mockingbird because there is just a challenge. I want to say Missouri, where students were reading Dear Martin in class. There was a complaint and the book was replaced with To Kill a Mockingbird, which is heartbreaking because Dear Martin is a contemporary story of a black boy and his experiences with racism. Whereas To Kill a Mockingbird is by a white author about racism, but in a capacity that has merit...

BROOKE GLADSTONE – In a 1950s capacity perhaps?

KELLY JENSEN There you go!

BROOKE GLADSTONE Where there were many fewer people getting to speak about their own experience directly and being paid attention to.

KELLY JENSEN Yeah!

BROOKE GLADSTONE Is that what you mean?

KELLY JENSEN Books like To Kill a Mockingbird are being reevaluated for whether they are the best book to address racism in the classroom. They're still available. They're still widely read, they're still recommended. But the move has been to include more books by black authors who can share from a perspective that To Kill a Mockingbird simply can't. Schools updating their curriculum have also been used as a conservative talking point of, well, they're removing books from the classroom, too. This is a willful misrepresentation of what's actually happening, and it gets that base riled up.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Could you take me through the process of challenging a book, and how long does it take for a book to be pulled from the shelf or not?

KELLY JENSEN So it's going to vary. Typically, what happens is a parent or a community person will file a complaint. Most libraries have a form. What books are you complaining about? Why are you complaining about it and did you read the material in full? Typically, the process is there is a committee that will meet and discuss the book. They will all read it, they will read the professional reviews, and then they'll determine whether or not it's appropriate for their community. Now, though, we're seeing more state governments stepping in, demanding schools and libraries look for these particular books in their collections. So in Texas, it's a list of 850 books seemingly slapped together from some quick research. So there's this tension now that whatever the schools policy is might not be enough to protect their expertise in doing their jobs. Instead, it's being handed over to the state.

BROOKE GLADSTONE My understanding is, in some places, the policies public library systems use are vague enough to give room for an interpretation so they can just pull things without a formal complaint because there wasn't one outlined.

KELLY JENSEN The Wake County Public Library system in North Carolina pulled Gender Queer from their shelves. I looked and looked for their collection development policy. It was very vague. It didn't have a chain of command a set of steps that happen when there's been a book complaint. There had been a series of emails about the book and ultimately their collection development manager decided to just pull it. This is Wake County. This is the largest library system in North Carolina, so library workers within that system complained. The library board wondered what happened. At the end of the day, not only was the book put back on shelves, but the collection, development policy and procedures for a book challenge were updated and made much more accessible.

BROOKE GLADSTONE How often do you think this happens where no one really knows?

KELLY JENSEN It requires somebody speaking out. I read about it in one of the North Carolina newspapers –Gender Queer being pulled. I put in a FOIA asking for emails and found my answer right in there. It was like an external group. Some of the motivation could be that the Wake County Public School System had received a number of complaints from parents, and a couple of those parents filed police reports about this book. Well, that ties back into obscenity and pornography laws. You can see the line between the two thoughts. Maybe Wake County Public Libraries was trying to ward off a potential challenge in pulling the book

BROOKE GLADSTONE is the concern that public libraries will be tailored to middle schoolers?

KELLY JENSEN Some of these challenges in public libraries in particular don't necessarily want the books pulled completely but want them very difficult for young people to access. In Jonesboro, Craighead County, Arkansas. What they have been doing is moving these books from the children's collection to a shelf that is now next to the children's librarian desk. So a 10 year old who wants to read this book, let's say that the book is It's Perfectly Normal. That's another one that's gotten challenges this year. It's a puberty book with illustrations appropriate for eight year olds, and up to a ten year old wants to look at that book. They now have to walk up to the library desk to browse these shelves. Well, that kid has now made it clear that they're looking at materials that people in the community think aren't appropriate. It's such a huge deterrent.

BROOKE GLADSTONE These school board meetings are the people objecting to the books mostly white? I mean, given the way critical race theory is often tied up in education censorship, what's the role of race in these disputes?

KELLY JENSEN Oh, it's absolutely primarily white. Out here, I believe it was Downer's Grove High School. This particular meeting also brought in the Proud Boys who are, you know, white supremacists. And so there's this pride that I am seeing in many of these school board meetings. It's white pride, and it's very clear this isn't about the kids.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Thank you very much.

KELLY JENSEN Yeah, thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Kelly Jensen is an editor at Book Riot. This conversation first aired in February.

Coming up, it's all framed as a parent’s rights issue, but it's not always about the children. This is On the Media.

[BREAK]

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. The conservative Education Advocacy Network: Moms for Liberty, launched in 2021 and claims to have amassed nearly 100,000 members to date. At the group's first ever summit last month, hundreds rallied around the goal of winning seats on school boards around the country. At a hotel in Tampa, Florida, they used Wi-Fi hotspots named We beat school boards and don't teach gender ID. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis lent his support.

[CLIP]

RON DeSANTIS Now's not the time to be a shrinking violet. Now's not the time to to let them grind you down. You've got to stand up and you've got to fight. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE But these and other self-titled parental rights advocates don't appear to be fighting to expand their children's education. A trend in the past year's school board showdowns are parents seeking to limit curricula. To remove whatever from science or history or English class that makes them uncomfortable or might make their kids uneasy. But in the debates over curricula, there remains a fundamental legal loose end. Who does decide what to teach kids? How much do parental rights figure into the mission of public education in American democracy? In February of this year, I spoke to Jennifer Berkshire and Jack Schneider are hosts of the Education Podcast: Have You Heard and coauthors of The Washington Post article: Parents Claim They Have the Right to Shape Their Kids' SchoolCcurriculum – They Don't.

JACK SCHNEIDER Parents do have rights and they can make choices. Their rights have been very clearly defined. Legally, they can, for instance, withdraw their kids from the public education system and send them to a private school. But parents aren't the only ones with rights. Children themselves have a right to an education, and parents do not simply have property rights over their children. Their children are both independent actors who need to be treated with dignity and respect, and who have a right to be exposed to ideas that may not align with the ideas that they're exposed to at home. And they are future citizens who we all have a stake in.

BROOKE GLADSTONE In your piece, you guys wrote that common law and case law in the U.S. have long supported the idea that education should prepare young people to think for themselves, even if that runs counter to the wishes of parents. And you quote the legal scholar Jeff Shulman, who said this effort may well divide child from parent, not because socialist educators want to indoctrinate children, but because learning to think for oneself is what children do. OK, what is the common law and case law? How do we see it play out?

JACK SCHNEIDER The system is not designed to alienate young people from whatever values and beliefs they're exposed to at home. For the most part, that isn't really what happens. But in cases where parents, let's say, don't want young people exposed to even basic things like the ability to read and write, the compelling state interest in preparing somebody to participate as an equal member in a Democratic Republic trumps those parental desires to, let's say, shield a young person from the world.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And that's implicit in the law that requires kids to be educated up to a certain age.

JACK SCHNEIDER Right. It's a part of legal interpretations. They're right. It doesn't say in state constitutions that if parental desires conflict with this law, then parents lose. Right, That's a part of what courts have wrestled with over the years. And sometimes they've struck compromises like in the Supreme Court's Yoder decision, where they upheld the fact that there is a compelling state interest in young people receiving an education, but also respected the Amish desire to not send their kids to school past a certain age.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Now in The Post piece again, again you wrote that U.S. law has long supported the idea that education should prepare young people to think for themselves, even if that runs counter to the wishes of parents. Can you give some examples of that?

JACK SCHNEIDER The teaching of evolution. Ultimately, the desires of parents from particular religious backgrounds and traditions did not win out over right of schools to teach what's in accordance with science. A parallel example today would be teaching climate change. There are certainly parents less likely because of their religious backgrounds, then because of their political persuasions who don't want climate change being taught as a fact, they don't want it being taught at all. Schools do not need to then stop teaching climate science merely because some parents find it to be in violation of their political ideology.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Jennifer, you wrote that this actually isn't the first time we've seen a push for parents rights that we saw this happening back in the 90s, for instance.

JENNIFER BERKSHIRE What's amazing is if you start poking around in the 90s, you'll find, you know, an unbelievable amount of media coverage of the parent rights issue, including by columnists who are still writing today. A lot of it started as the culture changed to include, you know, more recognition of gay and lesbians. And so there was a big backlash in New York City against what was known as a rainbow curriculum. And the idea that kids were going to be reading books like Heather Has Two Mommies. Parents felt like they were losing control over the ideas that their kids were being exposed to. There was a deep-pocketed, well-organized push to get parents' rights language on the books in every state, and then it ran out of steam for reasons that I think are really instructive for us today.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Mm-Hmm.

JENNIFER BERKSHIRE One of them I learned about reading a George Will column. He was very concerned that putting language like this in constitutions would set off an explosion of litigation. And he asked, You know, do we really want to turn every parent's cultural grievance into a lawsuit? And so the movement ran up against another pet GOP cause at the time, which was tort reform. Right?

[BROOKE CHUCKLES]

JENNIFER BERKSHIRE Fast forward to today. You know, we've already seen this just explosion of these education gag orders across the country. It's very much a wedding of what law professor John Michaels describes as the industrial grievance complex with the school wars. It was one that was rolled out in Oklahoma just this week that if a teacher teaches something that goes against a child's religious beliefs, that the teacher will have to pay $5000 out of his or her own money. And if the teacher is found to have been the beneficiary of something like a GoFundMe or, you know, an organization stepped in. The teacher will lose their license in Oklahoma for five years.

BROOKE GLADSTONE [DEEP SIGH] Wow.

JENNIFER BERKSHIRE So it's this incredible yoking of this moment of grievance to really encouraging people to become their own private litigators. And you know, these bills, these education gag orders now affect a third of the students in the country.

JACK SCHNEIDER And this is not really a new strategy. If you go back to the 1960s, you can read historian Richard Hofstadter writing about what he called 'the paranoid style' in American politics, and he was talking about the Goldwater movement, but it really applies today. His assessment of how much political leverage, I think was his phrasing, can be got out of the animosities and passions of a small minority, if you present to them a kind of all-powerful boogeyman. That's why I think that Jennifer and I tend to see this as a cynical political movement because it's politically effective, but it's not in response to any major shifts in the rights that parents have had historically versus the rights they have now, or really the basic ways that schools are operating.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Why do so many core debates in our country end up in school board meetings?

JACK SCHNEIDER Well, one reason is that young people enrolled in the schools who are today ages 5 to 18, 10 or 20 years from now, they'll not only be voting, many of them will be running for offices and we'll be voting for them. A second reason for this is there are roughly 100,000 public schools across the United States. And these are simultaneously government institutions. They are institutions that belong to local communities. They are manifestations of our public life together. And given the decline over the past several decades in civic associations and in other forms of public life, the schools are often the only place where people are coming together and engaging in these kinds of civic activities.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Are there a ton of parents fighting for their kids to learn history and science, fighting for books to stay on shelves and in curricula?

JENNIFER BERKSHIRE We see polls that show that the number of parents who want their kids to be exposed to, quote unquote honest accounting of history that they far outnumber the parents whose voices are so loud in this debate. But the problem is that the kinds of scenes we've been witnessing at these school board meetings, I have talked to people all over the country who describe the demoralizing effect of being shouted down. You know, of being too fearful to speak up at a meeting. They really have an anti-democratic effect. What's troubling is that as things move on to the book banning phase, often you have students speaking out and saying, I need to be exposed to ideas like this. They're going to end up on the receiving end of this kind of anti-democratic action, which I think sends a powerful signal that you're better off, just not speaking up. So the loudest voices at that public comment section of the school board meeting, often it's the woman at the Virginia meeting who says, you know, we're coming back and we're bringing our guns.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So there are a ton of parents who feel it's important for their kids to learn history and science, but they aren't loud enough.

JENNIFER BERKSHIRE I think that that's really true, and I think the other thing that's going to be very interesting to watch is the more these bans go into effect, limiting what kids can learn, the more kids own futures are going to be limited. And at a certain point, the affluent suburban parents who we complain about so much that they do everything they can to gain advantage for their kids. Well, at a certain point, it's going to, you know, make a difference in something like an AP test or a college admission. They're going to end up learning less as a result. Once parents start to process that, the real backlash to this is going to happen. We've already seen this in states where, you know, legislators have really pushed to defund public schools for ideological reasons. There's a certain point where parents who have not been involved before start to see that this is making a difference for the worse in their own kids lives. And that's where the backlash really picks up steam.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Jack, Jennifer, thank you very much.

JENNIFER BERKSHIRE Thanks so much for having us.

JACK SCHNEIDER It was great to be here.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Jennifer Berkshire and Jack Schneider, are coauthors of the book A Wolf at the Schoolhouse Door: The Dismantling of Public Education and the Future of School. This conversation first aired in February. Coming up, the historic lawsuit over censorship. One kid was born to bring. This is On the Media.

[BREAK]

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. Now we turn to the rights of students and the authority of school boards. This year marks the 40th anniversary of Island Tree's School District vs Pico. The first and only time the Supreme Court considered the question of book removal in school libraries. In February, our correspondent, Michael Loewinger., tracked down the main plaintiff from this nearly forgotten case.

STEVEN PICO You know, we're being taught in schools that book banning only occurs in totalitarian countries, and you wake up one day and you're not allowed to read a book in your own school because it was removed from all the shelves.

MICAH LOEWINGER This is Steven Pico, who would end up finding his way to the Supreme Court some years later. But in 1976, he was still a 17 year old student at Island Trees High School on Long Island in New York. He discovered his life's calling the day he learned that a list of books had been removed from his school district's libraries

STEVEN PICO From the high school library. Nine books were banned. The Naked Ape by Desmond Morris, Down These Mean Streets by Piri Thomas.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT They include such books as Sold on Ice by Eldridge Cleaver. The book banner said that he was anti-American and that he hated white women. And then there, Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut Jr. He made the list because he called Jesus a man with no connections. And then there's The Fixer by Bernard Malamud. They said that that was anti-Semitic. [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER There was also Best Short Stories by Black Writers, an anthology edited by Langston Hughes that featured work by James Baldwin.

STEVEN PICO Go Ask Alice by an anonymous author

MICAH LOEWINGER Laughing Boy by Oliver Lafarge,

STEVEN PICO Black Boy by Richard Wright.

MICAH LOEWINGER and A Hero Ain't Nothing but a Sandwich by Alice Childress.

STEVEN PICO Also from the Junior High School Library, one book was banned an anthology called A Reader for Writers, edited by Jerome Archer

MICAH LOEWINGER The Island's Tree school board targeted these books after three of its members had traveled upstate for a conservative conference, run by a group called Parents of New York United.

STEVEN PICO They went outside my community and found a list on a table at a meeting of objectionable books, and then they went back to our library and they searched the school and said, OK, well, we found 11 books on this list. We're going to remove them. Now, what does that mean? It means no student ever objected to any of these books. It means that no parent in the community ever objected to any of these books. No one in the community had objected to any of these books.

MICAH LOEWINGER Would it have mattered if people were objecting to the books?

STEVEN PICO In principle, no. But in my case, it came from a political movement that was going across the United States, and many people today can understand what I'm talking about. The school board, which is publicly elected, sent out a press release, a press release said, while at a conference, we learned of books found in schools throughout the country, which were anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic and just plain filthy. To date, what we have found is that the books do, in fact, contain material which is offensive to Christians, Jews, Blacks and Americans in general. In addition, these books contain obscenities blasphemies, brutality and perversion beyond description.

MICAH LOEWINGER An interesting wrinkle in all this is that Stephen Biko had gotten to know the members of the school board personally because he was Student Council president, and when he challenged them on their decision, he started to suspect that they were cherry picking passages

STEVEN PICO I had read. I'd say a number of the books that were removed. I think the one that probably touched me the most was Go Ask Alice.

[CLIP]

ALICE Hello, diary. My name's Alice. [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER Which was widely known to be a cautionary tale about a 15 year old who runs away from home and starts doing drugs.

[CLIP]

ALICE No Jobs anywhere but plenty of dope. How do you pay for it? Something else? [END CLIP]

STEVEN PICO They didn't read the book in its entirety, they said. Here's an excerpt, Steve. So this is these are the words of Alice quote. 'It might be great because I'm practically a virgin in the sense that I've never had sex, except when I've been stoned.' So what I did as a 17 year old is I opened the book and I'm searching for this excerpt.

MICAH LOEWINGER He found that in context, that passage had a completely different tone and meaning. Here's what followed the excerpt.

STEVEN PICO Then practically a virgin in the sense that I've never had sex, except when I'd been stoned. And I'm sure without drugs I'd be scared out of my mind. I just hope I can forget everything that's happened when I finally get married to someone I love. That's a nice, secure thought, isn't it? Going to bed with someone you love.

MICAH LOEWINGER Then there were the school board's problems with A Hero Ain't Nothin but a Sandwich by Alice Childress,

STEVEN PICO Which was also made into a pretty famous movie. The book was banned for two reasons. First, because the word ‘ain't’ appears in the title, and the second reason was a passage from the book spoken by Nigeria Green. and Nigeria Green was a black teacher in a Harlem school. In the book, and he said…

[CLIP]

NIGERIA GREEN We all know that George Washington was a slave holder, but he was also...

CLASS First president of the United States.

CHILD Also father of this country.

NIGERIA GREEN Oh, George was the father? He sure got around, didn't he? [END CLIP]

STEVEN PICO The school board said the passage was anti-American because it spoke disparagingly of one of the founding fathers. I lived in an all-white school district and that's why James Baldwin was targeted and Alice Childress and Langston Hughes and Richard Wright. They were targeted because they were minority ideas in a suburban white community.

MICAH LOEWINGER Shortly after the book removal, Pico got in touch with the American Civil Liberties Union.

STEVEN PICO I told them that I knew of the book, banning that I was upset by it and that I wanted to challenge the constitutionality of it.

MICAH LOEWINGER I have to say it's kind of mind boggling that you, as a high school student, your first reaction would be I would like to challenge the constitutionality.

STEVEN PICO I think when people get involved in a personal way, in an intense way with any issue, it's almost meant to be. I was born to be the plaintiff in this case.

ARTHUR EISENBERG He was very thoughtful, very sophisticated for a high school student.

MICAH LOEWINGER This is Arthur Eisenberg, one of the lawyers responsible for crafting the legal arguments that would end up before the Supreme Court.

ARTHUR EISENBERG When we heard about the incident collectively at the New York Civil Liberties Union, our impulse was that this is a case of censorship in violation of the First Amendment.

MICAH LOEWINGER The ACLU had Steven Pico encouraged four other students to join him as plaintiffs, including at least one who was young enough that he or she would still be in the school system should the case drag on for a long time, which it did –– five years. He chose Russell Rieger, age 17, Jacqueline Gold 16. Glenn Yarris, 16, and Paul Sochinski, 14. Arthur Eisenberg began representing the five students after the District Court ruled in favor of the school board.

ARTHUR EISENBERG The school board comes into court and says, Yes, we censored these books because they are inconsistent with our political philosophy because they are anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic and just plain filthy. But the school board's argument was we are the democratically elected body to make judgments about curriculum and the contents of the library. That was at the heart of their argument and that was accepted by the District Court. And so when we had to take an appeal, we had to explain why that theory was wrong and why the First Amendment was violated.

MICAH LOEWINGER Eisenberg used a couple different legal theories, but the most prominent one, the one that would feature most in the Supreme Court case was this.

ARTHUR EISENBERG We argued that school officials and school boards have some discretion regarding the curriculum and regarding what is taught in the schools, but they cannot exercise that authority in a way to impose a narrow orthodoxy of views and values, and they cannot exercise that authority consistent with the First Amendment. In an effort to suppress ideas that they don't like. Ultimately, the Second Court of Appeals bought the argument.

STEVEN PICO So we won, and the books were to be returned. So it was the school board that appealed to the US Supreme Court to intervene.

[CLIP]

FRANK MARTIN The issue here is not the books. What's at issue here is local control. [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER This is Frank Martin, who was one of the leaders of the Island Tree School District at the time, speaking with CBS after they lost in the Court of Appeals.

[CLIP]

FRANK MARTIN Does the courts decide what books go into a school library or do the local taxpayers and locally elected school board their representatives to select what goes into the schools [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER While they are waiting for the Supreme Court case to begin, Pico upped his media game. Since he'd first sued the school board. He'd been a guest on The Phil Donahue show. He'd spoken at press conferences with Kurt Vonnegut, Alice Childress and some of the other authors whose books have been removed from the library. Much of this while he was a student at Haverford College.

STEVEN PICO I worked my butt off throughout my entire college years to make sure it was kept alive in the media that people knew the stakes.

MICAH LOEWINGER From the very beginning. It's clear that your intention was to challenge the constitutionality of removing books from school libraries. But then, many years later, when the Supreme Court chose to hear the case, there was a chance that the court might make it constitutional and would sort of supercharge this kind of censorship. Was there a moment when you were nervous about what you'd gotten yourself into?

STEVEN PICO You bet. You're exactly correct. You're very astute. I thought we would win the case. But then in 1981, Potter Stewart left the court.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Justice Stewart resigned after nearly a quarter of a century on the court.

RONALD REAGAN I'm pleased to announce that I will send to the Senate the nomination of Judge Sandra Day O'Connor of Arizona Court of Appeals for confirmation as an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court. [END CLIP]

STEVEN PICO And it was hailed as this great opportunity for women in America, and I looked at it differently because, yes, there was a female justice, but she was going to vote against me and I realized that this is going to be a very close decision. The day that we were at the Supreme Court, I was interviewed on all the daily news, the morning shows and the CBS correspondent said to me, Do you really think you're going to win here? And I was like, We might lose five four, we might win five four, but I'm sure it's going to be a five four decision. And he said, You're so naive. I've been the law correspondent at CBS News for 30 years, and you're going to lose seven two. You're only going to have Brennan and Marshall on your side.

[CLIP]

JUSTICE BURGER We'll hear arguments next in the Board of Education against Pico and others. [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER On March 2nd, 1982, the court heard oral arguments from both sides. And by this time, the school board had dropped the whole anti-American, anti-religious argument and instead were insisting that the books have been removed because of their so-called vulgarity.

[CLIP]

GEORGE W LIPP JR My position is initially that an examination of the record and if the justices choose the books themselves, will indicate that there is absolutely no political motivation. However... [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER An argument which was rejected by Pico's litigated.

[CLIP]

ADAM H LEVINE They may say that, and they may want the court to believe that's what went on here, but they did in fact, make some very explicit political judgments. [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER Then, after four months of deliberation...

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT The Supreme Court today sharply curbed the authority of local school boards to ban books from school libraries. The landmark decision split the court on a five to four vote, and Chief Justice Warren Burger, speaking for the minority, called the ruling a startling erosion of the power of local school boards. [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER Stephen Pico and the president of the Island Free School District were interviewed after the verdict was read.

[CLIP]

STEVEN PICO It's a fantastic decision. It's a anyone that respects the First Amendment and the free flow of ideas is overjoyed today. [END CLIP]

ADAM H LEVINE This is definitely a defeat today. It's a sad day in this country for local control. [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER But this initial coverage didn't capture the complexity of the decision. This wasn't like Roe v. Wade, where you had one big opinion that a majority of justices signed on to that ultimately dramatically changed the law. In the Pico case. There were several different opinions, none of which received a clear majority. Looking back, Arthur Eisenberg is most focused on two of the seven opinions, one in favor of the school board written by Justice Rehnquist, joined by two other justices and one written by Justice Brennan, who wrote the leading opinion in favor of Pico. Joined by three.

ARTHUR EISENBERG Justice Brennan essentially said that school board members cannot exercise their authority to suppress ideas that they do not like.

MICAH LOEWINGER In effect, Justice Brennan argued that students have a First Amendment right to receive information, an idea that had never been extended to school libraries.

ARTHUR EISENBERG He said that in essence, if a school board consisting of Democrats were to decide to ban all books about Republicans and all books by Republicans, that would be impermissible.

MICAH LOEWINGER Yeah, seems about right.

ARTHUR EISENBERG And Rehnquist turned around and said if it's a principle which holds that school board members should not suppress ideas they don't like – why is that principle limited to the removal of books? Why wouldn't it even apply to the purchase of books to the maintenance of the collection?

MICAH LOEWINGER So here Rehnquist is saying that Brennan's position could introduce problems for school boards like what about all the books that a school library never had in the first place? Are you really saying that the school censored those ideas as well?

ARTHUR EISENBERG And I don't think Brennan or we had a clear enough answer to that. Rehnquist's problem with Brennan's argument was it's true Rehnquist concedes that if they did it because they don't like Republicans, that would be impermissible. But it's possible they decided not on the basis of ideology and not on the basis of politics. But they made their decision based upon the vulgarities in the books, and that's what I'm dissenting from Brennan's opinion.

MICAH LOEWINGER The vulgarity vs. political question was another big point of disagreement. Justice White, who made the deciding vote – the fifth vote in favor of Stephen Pico and the ACLU, didn't sign on to Justice Brennan's opinion because he didn't think the motivation of the school board had been settled.

ARTHUR EISENBERG You know, I often say that we won the case by a vote of four one four. We had four votes and the school board had four votes and Justice White couldn't make up his mind, so we sent the case back for trial.

STEVEN PICO They said that a trial should be held to determine the motivation behind the book banning.

MICAH LOEWINGER Steven Pico.

STEVEN PICO And because the school board did not want to go to trial, they decided to return all the books to the shelves because their motivation in banning books was clear. I wanted to see these books returned to the shelves, and I wanted a precedent set around America so that this wouldn't be happening again and...

MICAH LOEWINGER But It is happening again!

STEVEN PICO Well, it is happening again, because progress is slow, and you know that. You know that in the fight for constitutional rights, it takes decades to get things done.

MICAH LOEWINGER The Pico case remains the one and only time the Supreme Court considered the question of book censorship and school libraries, which is why I'm kind of surprised to not hear it discussed in the press more often. One reason might be that it didn't set a clear precedent. And another is that Steven Pico refused to participate in a sort of Hollywood mythology that tends to help activists stick in our historical memory.

STEVEN PICO I've turned down Columbia Pictures, I've turned down the New York Times magazine section, and I've turned down the opportunity to to write a book.

MICAH LOEWINGER Why?

STEVEN PICO Because I didn't want to be seen as profiting from something that I really cared about. If they wanted to do a movie that wasn't about my personal life. They wanted to do a serious movie about book censorship, then I probably would have collaborated with them, but they really were looking for a private story. And to me, there is no private story here.

MICAH LOEWINGER Pico has mostly retreated from the extremely public life of a Supreme Court litigant. Nowadays, he's a painter and sculptor, and he writes for his site Art Lovers Travel dot com. As for Arthur Eisenberg, he's never stopped thinking about this case.

ARTHUR EISENBERG People have asked me what my favorite case was in my four decades at the Civil Liberties Union, and this is the case. Because of the evolving nature of my thinking about it.

MICAH LOEWINGER Are you regretful at all?

ARTHUR EISENBERG I–I'm, I'm look. We didn't create the law that we would have liked.

MICAH LOEWINGER His first eureka moment. A new way of thinking about the Pico case hit him about eight years later.

ARTHUR EISENBERG When I was working on a case involving the funding of family planning services, where the government said we're the funding authority, we can tell doctors that they can't talk to their patients about abortion. It occurred to me that maybe this was one of those relationships that should be protected.

MICAH LOEWINGER Then there was this episode in the late 90s when New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani lost a court case with the Brooklyn Museum when he threatened to evict the museum if it ran an exhibition that featured a controversial depiction of the Virgin Mary.

[CLIP]

RUDY GIULIANI What they did is disgusting. It's outrageous. You could call it anti Christianity, but anti-Catholicism in particular because...

BROOKLYN MUSEUM The mayor is saying in effect, if there's a book in a library that we fund, I can take it out if it is offensive. That is profoundly dangerous. [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER Ding! That's that's when the light bulb over your head lit up.

ARTHUR EISENBERG Yeah, exactly.

MICAH LOEWINGER But it was too late.

ARTHUR EISENBERG Exactly. It was a little too late for the Island Tree's case. But if you look back when state funded universities were first created in this country, scholars fear that legislators would use the power of the purse to dictate the content of curricula. And this concern gave rise to principles of academic freedom, which insulated lectures and writings of academics from influence by the funding sources – governmental as well as private. The lesson is this: Just as academic judgments should be left to the academics, curatorial judgments should be left to the curators, and decisions about the content of library collections should be left to the librarians. And I mentioned this theory because one of the arguments that the school district made was, Look, we bought these books, we paid for them. We can make the judgment that these books are impermissible because we paid for them.

MICAH LOEWINGER He calls his first idea the academic freedom theory. Here's another legal argument that he thinks might have been persuasive in the Island Tree's case.

ARTHUR EISENBERG Public education is not just about reading and writing and arithmetic. That an element of a sound basic education involves being educated in democracy and ideological diversity and pluralism, are foundational democratic values. And democracy rests on the power of reason through public discussion, and the remedy for bad ideas is not coerced silence, it is not censorship, but more speech to correct those errors.

MICAH LOEWINGER Because one of the things that Brennan did point out in his opinion, is that the Supreme Court has invalidated education laws passed by state legislatures.

ARTHUR EISENBERG In one case, Nebraska prohibited the teaching of foreign languages in schools, and in the other case in Arkansas. There was an effort by the Legislature to prohibit teaching about Darwin in schools, and the Supreme Court invalidated both of them.

MICAH LOEWINGER Either of these arguments, the academic freedom theory or the democratic education theory, might have been effective in the Pico case. Eisenberg thinks they may have helped set a precedent that would have stopped the kind of book removals we're seeing today. If you could go back in a time machine and apply one of these different legal theories to that case, would you?

ARTHUR EISENBERG Yes, yes, yes, I would.

MICAH LOEWINGER A case that coulda, woulda should've been bigger – more definitive, more precedent setting. 40 years later, a similar moral panic has taken hold in our discourse and in our schools. Or maybe it just never went away. It's hard not to look at the Pico case and wonder if a different ruling informed by what we know today might have been able to save our schools and our democracy a whole bunch of trouble. For On the Media, I'm Micah Loewinger.

BROOKE GLADSTONE That's it for this week's show! On the Media is produced by Eloise Blondiau, Molly Schwartz, Rebecca Clark-Callender, Candice Wang and Susanne Gaber, our technical directors Jennifer Munson. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media, is a production of WNYC Studios. I'm Brooke Gladstone.