Our Bodies, Ourselves

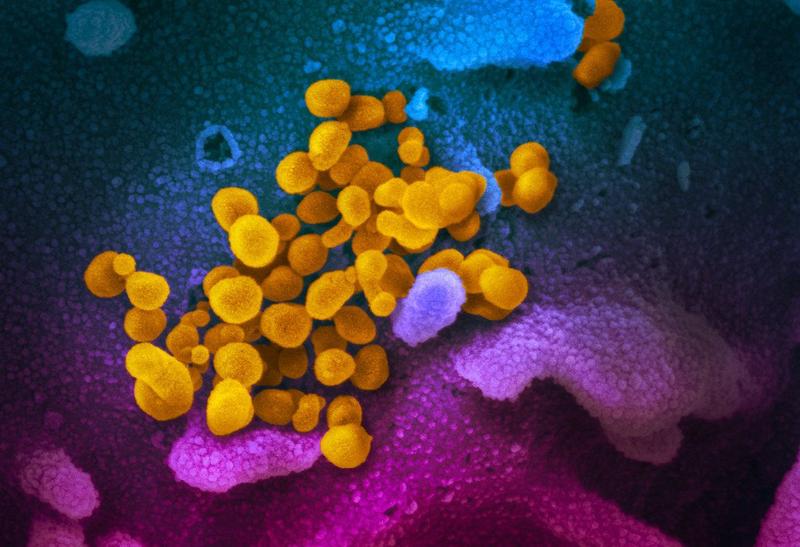

( NIAID-RML )

BOB GARFIELD On the matter of COVID-19, the government has coordinated and streamlined its messaging. But is it the right message?

JON COHEN What's really necessary is for the people in the government who don't know the details to stop telling us things like, “there will be a vaccine in one year.” That's not helpful.

BOB GARFIELD From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And I'm Brooke Gladstone. From the bubonic plague to the AIDS crisis to today, epidemics have exposed some of humanity's darkest impulses.

FRANK SNOWDEN The hunt for witches, pogroms against Jews, xenophobia unleashed societies coming to a halt.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Plus, U.S. officials impose a kind of censorship at the U.N.

FRANÇOISE GERARD We've seen them object to words like sexual and reproductive health. Phrases like reproductive rights to the word gender itself.

BOB GARFIELD It's so it's all coming up after this.

From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And I'm Brooke Gladstone with a few questions. Should we throw our resources at trying to bar the door against COVID-19 or trying to shield our most vulnerable from its sometimes deadly impact? Should we stockpile and mask ourselves or just wash our hands and go to work? Is the death rate higher than we think? Please, God, tell me it's lower.

[CLIP]

PRESIDENT TRUMP Well, I think the 3.4 percent is really a false number. Now, this is just my hunch. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE We don't know because the 3.4 percent mortality rate brushed off by the president is the World Health Organization's calculation derived mostly from the Chinese outbreak, which initially brought only the sickest to the regime's attention for which it was woefully unprepared. As The New York Times reported, the doctor leading the W.H.O’s coronavirus effort expects the rate to drop by half or more, once there's more data on the infected and leading, U.S. health officials suggest it could be lower still. We just don't know. We also don't know if the task force on messaging now led by Vice President Mike Pence will be straight with us. On Tuesday, during one of the regular tele press briefings led by Dr. Nancy Messonnier of the CDC, someone asked whether with the White House breathing down her neck, she could even speak freely.

[CLIP]

NANCY MESSONNIER As many of you know, I've been doing these briefings regularly since the start of this outbreak. And I think we at CDC have been very open and able to answer lots of different questions, including those posed on these conferences. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE He'd been very forthright a week before when she said it was a matter of when, not if we'd be prey to COVID-19 because it would come and it has. Two weeks ago, risk communication experts Peter Sandman and Jody Lanard wrote that, “The most crucial and overdue risk communication task for the next few days is to help people visualize their communities when keeping it out. Containment is no longer relevant.” We should have gotten that message by now. Those who closely follow public health, like Science Magazine staff writer Jon Cohen have known it for a while.

JON COHEN The story begins on January 8th with the Wall Street Journal story that tells us there's a new coronavirus. That's when all of the reporters who cover infectious diseases went from, “oh, there's something happening in China to oh, there's something happening in China.” And I started communicating with Chinese scientists. It became abundantly clear the Chinese government was not allowing their scientists to speak openly. That's not surprising. I've reported in China for many years and I've often confronted that reality and I'm relieved that I don't face those obstacles here. There has been a mandate to direct everything through the White House. That doesn't mean people don't speak to journalists. Of course they do. They just can't do it on the record. You can't quote them and they're afraid of saying something that will get them in trouble. The stock market tanks. Trump very clearly was concerned. And then you start getting this robotic sort of messaging. Talking point number one:

BROOKE GLADSTONE Here intoned by Trump:

[CLIP]

PRESIDENT TRUMP Because of all we've done, the risk to the American people remains very low. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE And his VP:

[CLIP]

MIKE PENCE The risk of infection to people in this country remains low. [END CLIP]

JON COHEN That's true. And then they tell us again and again, talking point number two, we have great professionals.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Then that's talking point three, we're closing the borders.

JON COHEN Talking point four, we've got vaccines and treatments in the works here. Overstating where they are in that pipeline. We're getting this messaging of, “Don't panic. There's going to be a vaccine. There are gonna be treatments.” We don't know that we're working on it. Science is all about going from what's possible to what's probable, but people want certainty.

BROOKE GLADSTONE How has the responsiveness of the government changed?

JON COHEN Brooke, you should also know that the National Association of Science Writers put out a statement calling on the Trump administration to allow government experts to speak freely. You know, the CDC made a testing kit that they sent out to public health laboratories. When those laboratories started to test drive the kits, a bunch of them said they don't work. There's a problem with one of the chemical reactions here. So I wanted to interview the same person, the laboratory scientists, and it looked like that was setup. And then the timing of this, with the Pence group taking over, I get an email back where the press person answers a couple of my questions but doesn't set up an interview. I request again, I want to speak to the scientist.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And they said no.

JON COHEN Nothing. In the end, I figured it out. I spoke to a lot of other people who could explain to me precisely why the CDC test had a problem, but I didn't get that from the CDC. And it's dangerous terrain. I could make a mistake more easily because I'm not speaking to the horse's mouth. I have a rule of thumb about being a journalist. Nobody owes me anything. I'm grateful that people share their time with me. But come on. I work for a publication that's widely respected and widely read around the world. Don't you want your best person speaking with me to get your message out as accurately as possible? It's baffling and it's counterproductive. We do have to be concerned about the messaging and about the fear that we create with people. That's real. I get it. But the notion that we got this one. Don't worry. No problem here. Hey, how many times did Trump say nobody's died from this yet? And we all knew all of us who covered it, we knew that was around the corner.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Everyone who is reading it knew it was around the corner.

JON COHEN So people aren't simply getting messages from the government. We're flooded with all sorts of messages. But, you know, there's a whole debate about can this be contained? And the experts I speak to are saying to me again and again, look, this is something that is gonna spread widely. We may well see 20, 30, 40 percent of the population has been infected at some point. We should do things to try to slow it spread. But can we contain it? Chase it back into nature. The people I speak to who are most in the know think Pandora's box has been opened, figure out how to live with it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE If there isn't trust in government pronouncements, doesn't this create a situation where people will be prone even more to conspiracy theories? Also prone to dismissing it.

JON COHEN You just put your finger on it. We have top government officials who are speaking accurately and openly. Tony Fouci is a point person. He's the head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Tony is credible. Debbie Bourke's yet another person appointed to head the task force with Pence. Bob Redfield heads the CDC. These people have all worked together for years and years and they're credible people. There are many government voices sometimes saying very different things. That's the problem. Their reaction to that problem is let's funnel this all down to one person with talking points. What's really necessary is for the people in the government who don't know the details to stop telling us things like, “there will be a vaccine in one year.” Stop it, please. That's not helpful. Don't send out messages that conflict with the science.

BROOKE GLADSTONE What happens if we get these mixed messages? What's the ultimate consequence?

JON COHEN People lose trust in you. And then when you really need to do something that you know is gonna be painful, they question it. If you have a trusted government saying, hey, we've got to shut down our football season, the NFL has got to shut down. I mean, I'm not saying that's gonna happen. But what if you have to go there? What if you have to up the ante? I mean, remember what China did. It shut down cities, 50 million people were quarantined in Hubei Province at least. Could the US government do that? Probably not. You know? But what if this were killing 50 percent of the people that were infected? Maybe we would go to these draconian measures, right. And you have to trust your government to do that. This is serious stuff, you know, and we are very bad at gauging risk. You know, we have a law that you have to wear a seatbelt. Why do we need a law? Come on. We all know seatbelts work. But we have a law because people wouldn't wear them otherwise they wouldn't wear motorcycle helmets otherwise. Our perceptions of risk are screwy. You know, if you ask a scientist, what's the case fatality rate of coronavirus? You're going to get a lecture. If you ask, what's the range of fatality? They’ll give you the range, the ranges from 0.7 to 18 percent, it’s all over the place.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Holy cow. What does that even mean?

JON COHEN What does it even mean? We see all these different things and then you try to figure out, well, what's the average what usually happens if you look at the biggest database, China. And you look at Wuhan, the hardest hit place, the case fatality rates like 5.7 percent, but Wuhan was overwhelmed. They had people being sent away from hospitals waiting in line forever. They couldn't diagnose quickly enough. If you look outside of Wuhan at the rest of China, it drops to 0.7 percent. What that tells me is if you have really good health care, you detect your infection early. If you're under 80 years old and you don't have underlying heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, your risk of dying is very low. It's less than 1 percent. But it could be that we're missing four times as many people as we are catching in terms of who's infected. Let's say, just for the sake of argument, instead of there being 90,000 people in the world with confirmed cases today, let's say there are a half million. That changes completely the percent of people who've died.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Right. It goes way down.

JON COHEN Right. We probably have a good sense of how many people have died, but we don't have a good sense of how many people have been infected. And that's how you calculate the case fatality rate. So people who aren't scientists, they get dizzy from all this, Brooke. They do. They're like, what? Just tell me the answer. And unfortunately, science rarely can give you a certain answer about things. I can tell you there is an existing flu vaccine. I'm certain about that. And I'm certain that it offers about 50 percent protection this year. I'm certain that if you get it, you're lowering your risk of flu and going to make it easier to determine whether you have COVID-19. I'm certain of those things. What I'm not certain about is whether you're going to get infected by flu or whether you're going to get infected by COVID-19. And what's going to happen to you? I don't know.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Well, thanks, Jon.

JON COHEN I hope that's helpful.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Very.

JON COHEN The risk is low, Brooke. And we've got a great team and they're doing a great job. And the risk is low. Did I mention that? The risk is low. Jon Cohen is a staff writer for Science Magazine.

BOB GARFIELD As the world struggles with the threat of pandemic, along with all of the attendant fear and uncertainty, there is a great deal to be learned from the past because communicable disease has haunted humanity for all of history. As such, the responses to coronavirus in our midst have a grimly timeless quality. In fact, to one scholar, epidemics are a great lens for peering into the values, temperament, infrastructures and moral structures of the societies they attack. Frank Snowden is a professor emeritus of the History of Medicine at Yale University and author of Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present. “An epidemic,” he writes, “holds a mirror to the civilization.”

FRANK SNOWDEN The bubonic plague in the 14th century shows what are our relationships to our fellow human beings.You read in Boccaccio about the terror from the plague husband, left wife and vise versa. Parents fled their children. One can see the scapegoating. The search for a demonic influence.This is not something that we ourselves did, of course. It's always some other group or person that we want to blame. The hunt for witches, pogroms against jews, xenophobia unleashed societies coming to a halt. It's something that seems, alas, to be with us since the very beginning. We can see it in homophobia in the American epidemic of HIV AIDS and the assault on Asian people today.

BOB GARFIELD I want to move on to a more modern infection bedeviling Napoleon. Let's start with his invasion of Russia in 1812, where his superior armies were overrun not by the czar's troops so much as what?

FRANK SNOWDEN Oh, dysentery and typhus. His military tactics were predicated on lightning strikes and sudden rapid movement. He wanted his army not to be laden down with supplies and with food, but to live off the land. And so he marched an army that was half a million men. Imagine the whole city of Paris going into Russia and Napoleon having decided not to take medical supplies, bandages or sanitary precautions of any kind. Of the time. And so they went into Russia marching for this vast distance in what was the immediate creation of what we might call a terrible urban slum living in the dung of the animals, and that they themselves made drinking water that was polluted in the rivers. And very soon they were immersed in a tremendous outbreak of dysentery that was killing something like 3,000 men a day. Then after Moscow, Napoleon finally decides that they can't survive a winter in Moscow, he has to return to France. Napoleon himself took off in a sled with a bodyguard and abandoned his troops. Only about ten to 15,000 returned to France, and almost all of those 480,000 or so died of first the dysentery and then the typhus. And there was regime change in France and disease had a major role in that.

BOB GARFIELD In the midst of Coronavirus, you're thinking of Napoleon and feeling a bit of déjà vu.

FRANK SNOWDEN I think about Napoleon a lot because it seems that he's a model of how not to react to the threat of disease that was about to overwhelm the 500,000 thousand men he was commanding and the larger society and empire for which he was responsible. He reacted by doing something that sounds very similar to the present day by saying it was false facts. We don't need to think about these diseases we're going to march on ever forward. So Napoleon seems to be someone who had contempt for the impact of the environment, nature, disease and the threat that it posed. Not willing to think of this in terms of planning and mobilizing resources. And deploying them and the way that people with knowledge and science and the lessons of history all urge should be done.

BOB GARFIELD And to your earlier point, he seems to take as a personal political assault the behavior of microbes.

FRANK SNOWDEN Napoleon took great umbrage that a disease could harm the almighty emperor of the French.

BOB GARFIELD Well, on the subject of politicization of pathogens, the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918 and 1919 killed more than 50 million people around the world. But in this country, officials soft pedaled the threat. Evan Osnos in The New Yorker talked about a political appointee named Wilmer Krusen and city's public health director who called the killer flu, “old fashioned influenza or grip.” And the news organizations played along. One headline in the Philadelphia Inquirer was “Scientific Nursing Halting Epidemic”, when, in fact the truth on the ground was horrifyingly different.

FRANK SNOWDEN There is a tendency of some people, when confronted by something new, not to admit that they don't understand, but instead to label it something different that they think that they can manage. That seems to me the story in Philadelphia and the story before us today.

BOB GARFIELD I want to turn to 1995 and the outbreak of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of Congo. And then eight years later in rural Guinea, in West Africa. The first response, at least in the West, was absolutely ignoring what was a significant, fairly localized public health crisis. And then once it came to western shores, in a very small number of cases, suddenly hysteria.

FRANK SNOWDEN The world wanted to turn its back on West Africa. It was Doctors Without Borders that got first involved and they pleaded for the intervention of outside nations. And this, they said, was the potential of a regional or even a pandemic outbreak. The World Health Organization sat on its hands. The American government did nothing until a physician and a nurse who were American and white, working in West Africa were stricken with Ebola and brought back to the states. And suddenly there was this wave of horror. “Oh, no, this can affect not just Africans, but white people.” It did lead at last to large scale intervention medically in West Africa, but it took an infection to invade white and American bodies before people could take it as something that had to be dealt with. That seems to me a really depressing moment in human history.

BOB GARFIELD And now we come to coronavirus, which seems to be playing out as scapegoating, xenophobia, opportunistic denial, medicine and epidemiology have advanced incalculably over the centuries. Has human behavior begun to catch up?

FRANK SNOWDEN We can see different actors in this drama espousing different solutions. The denial impulse. The blame impulse. The attachment to ethnic barriers to national barriers. But we also see Dr. Tedros of the WHO--

BOB GARFIELD That's Tedros Adhanom, the Director-General of the World Health Organization

FRANK SNOWDEN and lots of other people at NIH and the CDC and around the world and health ministries who are taking a scientific and community based approach to the disease, that it's about education, about involving the populace. It's about taking care of the entire globe. That is to say, your resources have to be deployed, not where there's money, but where there is need. And so masks and respirators and ventilators need to be moved to the place where they're required, not where there are people with lots of money to purchase them, whether or not they're needed. Dr. Tedros is having a very hard time getting the industrial world to release, for example, the funds to carry out a general international co-operative effort. And what does that say about us? Virologists all around the world have been expecting an event of this kind, saying it was inevitable. So why is it we weren't prepared? Bruce Aylward coming back from China was asked, “what is it that we need to do to be more prepared?” He said the first thing we need to do is to change our mindsets and begin to act in an international coordinated way based on truth and science, learning the lessons of history. It's not just a technical question of having a magic bullet, a vaccine. This is something that lies below that. The question is, are we willing and prepared to take up that challenge?

BOB GARFIELD Frank, thank you so much.

FRANK SNOWDEN Great pleasure to be with you. Thank you for having me.

BOB GARFIELD Frank Snowden is a professor emeritus of the history of Medicine at Yale University and author of Epidemics in Society: From the Black Death to the Present.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Coming up, the run up to Super Tuesday and its aftermath left the Democratic field littered with broken dreams.

BOB GARFIELD This is On the Media.

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD And I'm Bob Garfield. As you know, before this time last week, the high priests of the political word were performing rites of extreme unction for the campaign of Joe Biden.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT It is the drip drip drip that could become a drain for 2020 President, presidential hopeful named Joe Biden. He's not only slipping in the polls, he's also slipping in fundraising.

NEWS REPORT All the while, Joe Biden is struggling to hold on, in some respects, TV show energy. There were a lot of hundreds of empty seats. [END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD But then suddenly everything changed following poor results in the South Carolina primary. Pete Buttigieg dropped out and Amy Klobuchar dropped out and then on Super Tuesday, resurrection.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT 10 primaries now on Super Tuesday that have gone to Joe Biden, you see a narrow margin. Biden getting Maine, getting Massachusetts, getting eight others. Biden excuse me, Sanders with Colorado. [END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD Next thing you knew, Senator Elizabeth Warren and Mayor Mike Bloomberg had given up too, solidifying a showdown between Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden and how? According to Rachel Bitecofer of the Wason Center for Public Policy at Christopher Newport University, the answer is that voters were mainly motivated not by health care or economic justice or college debt, but by perceived electability to send Donald Trump packing, which she says should come as no surprise because it is exactly what explains the historic Democratic blue wave in the 2018 midterm elections. Back then, when political mandarins were debating whether the party would come in just over or just under the 23 seat gain needed to control the House, Bitecofer was all but alone in forecasting a 40 seat sweep. Afterwards, House Speaker-in-waiting Nancy Pelosi attributed it to America's insecurity about health care.

[CLIP]

NANCY PELOSI Health care was on the ballot and health care won. [END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD Nope. Bitecofer says it was about Trump and a harbinger of massive Democratic turnout in November, which she explained to us as she raced to catch a flight.

RACHEL BITECOFER What I am arguing is that the reason turnout in every election since Trump shot up 10 points is because of the agitation of the electorate, especially the Democratic and left-leaning independent portion of it, which was caught kind of sleeping in 2016 and had lower participation rates, now is suddenly very energized to vote.

BOB GARFIELD This is a phenomenon known in political science circles as negative partisanship. What exactly does that mean?

RACHEL BITECOFER Negative partisanship refers to the negative emotions people feel about the opposition party distrust, anger, angst, even hatred. I am arguing that that is definitely what is driving them to the polls where they were not showing up before. Keep in mind that there's just a lot less what they call crossover voting now. About 10 percent of Republicans vote for Democrats and 10 percent of Democrats vote for Republicans, in your average federal election. Polarization has really changed the way that people behave and you get these massive turnout swings.

BOB GARFIELD I just want to ask you about your methodology. How is it different from pollsters who slice the electorate into a trillion different demographics and then further slice it district by district around the country and the punditocracy that uses that to evaluate what's happening in the electorate?

RACHEL BITECOFER All I'm doing is taking well established findings from polling and political science research, which says demographics predict partisanship. Partisanship predicts voting. And that I'm using basically census data to say, here's where all the populations of latent Democratic friendly electorate was and I predicted that it was going to have a huge turnout surge that was going to make what looked like really friendly Republican territory turn into really friendly Democratic territory. Morning Joe panel sees that as “oh, Republicans change their minds and are deserting the Republican Party.” But actually, what's going on in that is different voters being agitated at the polls.

BOB GARFIELD The bottom line is that it's not the economy, stupid. It's not the health care stupid. It's the stupid president's stupid.

RACHEL BITECOFER I mean, that's definitely right. In 2018, I expected Republicans to do what Democrats had done once they seized power, Democrats took their foot off the gas. So what I expected was, you know, to some extent, Republicans are going to be fat and happy now and they're going to relax. But instead, because Donald Trump does this negative partisanship and he artificially inflames it so well amongst Republican rank and file voters that their turnout went up in the 2018 midterms and that really helped them in the Senate map--hold on to Texas, hold on to Georgia, hold on to Florida, where I thought those seats would probably flip and they probably would have. If Trump had not gone in and held rallies and told them, “I'm on the ballot, this is a referendum on me,” which is, you know, the exact opposite advice that he campaign consultant would ever give an incumbent midterm president. All right.

BOB GARFIELD Well, let's talk about campaign consultants, because in your New Republic piece recently, you said that Democratic consultants were telling the candidates in the midterm elections to stay away from Trump to avoid the subject, that there was some risk in alienating independents and moderate Republicans by going personal.

RACHEL BITECOFER When you look at the differentiation between the most timid of the Democrats and their strategies, what you'll notice is that the Republican turnout was the same number as other districts and their own turnout, especially amongst Democratic partisans, lagged. So the data is just not supportive of this idea that there were disaffected Republicans joining hands with Democrats to flip these districts. The districts flipped because millennials in the suburbs who had not been voting, many who are 40 now, they're 40 and 30 years old, they had not been voting before in midterms especially, and now they are.

BOB GARFIELD I've been using term conventional wisdom to describe what the anointed ones have told us is happening in the political landscape. You call that the “Chuck Todd theory of politics.” Tell me why.

RACHEL BITECOFER I don't mean to pick on Chuck. I could fill in the blank with any mainstream analyst, Chris Matthews, James Carville. I wish that we lived in a world in which, you know, there's these big swaths of independents and they were super uber informed and they could be swayed just by, you know, being more pragmatic and bipartisan than the other guy and that's what mattered to win a close election. But you just look pattern after pattern, a lot of them are not paying attention to politics at all. They're very emotive in their political attitudes. We sat through an impeachment trial in which a president was implicated day after day just in the absolutely jaw-dropping amounts of evidence and public opinion was completely inelastic to it. Right. So we're clearly living in a time period that is different than that conventional wisdom.

BOB GARFIELD The Chuck Todd's of the world had buried Joe Biden because he performed badly in the Iowa caucuses. He performed badly in New Hampshire and was becoming kind of a punchline. And yet he crushed Bernie Sanders and especially the other hopefuls in your world. This has nothing to do with Joe Biden, the candidate, it has to do with the phenomenon you're describing of just absolutely transcendent revulsion.

RACHEL BITECOFER Yes. To be fair to the Chuck Todd's of the world, I, too, looked at Biden. He looked dead in the water. He had no money. What it came down to is that when the nomination started to really look like it was going to go to Sanders, the idea of nominating somebody who has got the label of a socialist, I think there is this deep seeded fear that if the party nominated Sanders, they would lose not only the presidency, but their opportunity to hold on to Congress and to the Senate. The candidate doesn't matter much in 2020. You want to have diversity on the ticket. So since Joe Biden happens to be a moderate white male, you want to have ideological diversity. So someone who's more liberal and racial and gender diversity is someone who is a female person of color to balance out representation. But we are going to see turnout go up amongst young people if it's Biden or if it's Sanders, because people are responding to the threat of Donald Trump.

BOB GARFIELD Now, if one were in support of Joe Biden as a candidate, probably one would be constantly on edge that he would do something or say something just positively catastrophic. But if this cycle is indeed the ultimate expression of negative partisanship, what we learned from Trump is that there is nothing he can do or say that is going to change the overarching dynamics of the race because no one's going to vote against him.

RACHEL BITECOFER That's exactly right. Because Sanders or Biden, there is no liability. Either those men possess that Trump doesn't have a thousand percent more of a problem is the Democratic Party is inept at messaging and campaigning so that's where the weakness between nominating someone like Biden versus Sanders comes in.

BOB GARFIELD If you're right, then Joe Biden could shoot somebody in the middle of Orange Street in Wilmington, Delaware.

RACHEL BITECOFER Well. To a degree, the end of the day, Donald Trump's going to pull in somewhere around 47, 48 percent of the two party vote in these swing states, and the only question is, is it going to be enough like it was in 2016? Because the Republican Party is successful in getting the Not Trump coalition to fracture and waste votes on third party candidates or is it going to fall short because the vote winner in 2020 needs to crack 50 percent.

BOB GARFIELD There's something about your theory of the awakening of the formerly complacent Democrat that doesn't make sense. We've been hearing in the ongoing media narrative about the 20 million millennials who have never before voted and finally have their opportunity to cast their ballots in a way that can express their well-established desire for social and economic justice. And the candidate, Bernie Sanders, who has most made them an issue, but they didn't turn out. They didn't show up on Super Tuesday.

RACHEL BITECOFER We actually see a turnout surge amongst all voting groups right now. So even though youth voting is up right now, it is. It's up amongst all groups so it's not proportionately showing an increase all. So if there was a youth turnout surge, it would be because of Donald Trump, but not because of Sanders.

BOB GARFIELD One of the seeds of conventional wisdom that sprouted in the last few days was that the results are a reflection of educated Republican women in the suburbs having had enough of Trump.

RACHEL BITECOFER It's anecdotally true, but in terms of the overarching data story, it's about different turnout of millennials and independents who are left leaning and Democrats turning those districts in to demographically favorable districts for Democrats, not because Republicans had Kumbaya moment. Republicans are actually stoked on Donald Trump. They love what he’s doing.

BOB GARFIELD Rachel, thank you very much. Run for your plane.

RACHEL BITECOFER Yeah I’m trying, bye!

BOB GARFIELD Rachel Bitecofer is the Assistant Director of the Wason Center for Public Policy at Christopher Newport University.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Coming up, how much it'll cost you to use phrases like “women's health” and “women's rights” at the U.N., because Mr. Moneybags is the American president.

BOB GARFIELD This is On the Media.

This is On the Media. I'm Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And I'm Brooke Gladstone. This week, the Supreme Court heard a case challenging a law that would limit women's access to abortion in Louisiana, which is pretty much the same as a Texas law the court struck down four years ago, same law, but now argued before a different Supreme Court. Abortion rights advocates say the consequences if the court flipped could be dire. Meanwhile, next week brings world leaders to the United Nations, if coronavirus doesn't intervene to mark 25 years since reproductive rights were enshrined in international law. It happened in 1995 at the UN's Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. You might even recognize a line from then first lady Hillary Clinton's speech.

[CLIP]

HILLARY CLINTON If there is one message that echoes forth from this conference, let it be that human rights are women's rights and women's rights are human rights once and for all. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE But we've come a long way backward. The U.S. has exchanged its role as a prominent advocate for women's rights, for one, that aims to obstruct international agreements that uphold them. Here, Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar speaks for the White House.

[CLIP]

ALEX AZAR We do not support references to ambiguous terms and expressions such as “sexual and reproductive health and rights” in UN documents. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE Jessica Glenza who covers health for The Guardian, has the story of how the Trump administration is seeking to rewrite international norms about women's health, women's rights and gender equality by seeking to erase those very phrases. Here's Jessica.

JESSICA GLENZA To understand why Beijing was so monumental, it's worth remembering what came just before in the early '90s. Abortion opponents were on the outs politically, but they were drawing the national spotlight for extreme and at times violent protests.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT In San Diego this week, a clinic was sprayed with butyric acid, which creates a stench that lingers for months. [END CLIP]

JESSICA GLENZA It was 1993 and the U.S. was in the throes of intense, often violent clashes about abortion in Bill Clinton's first term.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT In Des Moines, a doctor's house was picketed. And in Milwaukee, shots were fired into a clinic's windows three times in the past two weeks.

NEWS REPORT And federal officials say they're limited by a recent Supreme Court ruling, saying demonstrations are protected by freedom of speech.

NEWS REPORT When a doctor was shot to death outside his Florida clinic by an abortion protester yesterday, the violence of this issue was raised to a tragic new level. [END CLIP]

JESSICA GLENZA That Florida doctor David Gunn was murdered in March 1993 by a shooter who reportedly yelled, “don't kill any more babies.” An anti-abortion group called “Rescue America” said the murder was justified and raised money for the killer's family. And then a few weeks later--

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT The U.S. abortion debate went transatlantic today and spilled over to Britain.

NEWS REPORT Members of the American anti-abortion group Operation Rescue led a demonstration in Birmingham, England today, staging a sit in at an abortion clinic, blocking the road outside and sparking a counter demonstration by abortion rights activists.

NEWS REPORT The protesters took to the streets hoping to support or denounce this man, anti-abortion rescue America leader Don Treshman. He was on primetime television last night drumming up support for his crusade.

DON TRESHMAN We've lost worldwide 130 million children to this horrible abortion. And we're just asking for our friends here to join us to fight one more Holocaust. [END CLIP]

JESSICA GLENZA That was Treshman on the BBC, where he appeared in a debate with Mo Mowlam, then a minister for women's affairs in the UK.

[CLIP]

DON TRESHMAN Ever since we've been in the island here, we've said we have no involvement in any of this type of activity. We don't condone it. We don't condemn it. We are not involved with it.

MO MOWLAM You don't condemn it?

DON TRESHMAN We don't condemn it because morally they can be justified. I'm not gonna pose my morality on anyone else. [END CLIP]

JESSICA GLENZA Treshman was arrested as he left the BBC studios and deported.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT The message from British authorities is: Yankee, go home. [END CLIP]

JESSICA GLENZA The next year, 1994, feminist leaders got together in Cairo, Egypt, for a conference on population. It was an alarming time. The world's population was expected to rise exponentially.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT In September, 150 members of the United Nations meet to decide what to do about it. They agree the key to decreasing the birthrate is giving women more control over their lives. [END CLIP]

FRANÇOISE GERARD What Cairo did was show the women's movement that it could transform a global agenda.

JESSICA GLENZA Françoise Gerard is the President of the International Women's Health Coalition, a nonprofit focused on global gender equality.

FRANÇOISE GERARD And the idea was that women should have control over their bodies, their reproduction, and they should have the information, the education and the means to do so in that battle is actually a human right. And it worked. And we've never looked back.

JESSICA GLENZA Well, until now.

[CLIP]

PRESIDENT TRUMP At the United Nations, I made clear that global bureaucrats have no business attacking the sovereignty of nations that protect innocent life. [END CLIP]

JESSICA GLENZA This year, Trump became the first president to ever address the anti-abortion protest march for life in person.

[CLIP]

PRESIDENT TRUMP Unborn children have never had a stronger defender in the White House. [END CLIP]

FRANÇOISE GERARD The Trump administration has made clear that it wants to base U.S. policy, both foreign and domestic, on extreme Catholic and evangelical ideology. At the U.N., we've seen them object to words like “sexual and reproductive health.” Phrases like “reproductive rights,” they've objected to “gender equality” as a phrase to the word “gender” itself. Gender equality is not a new idea. It's been in international documents for 25 years. So to have the United States now refused to agree to the idea that there is such a thing as gender equality is very destabilizing.

JESSICA GLENZA Can you talk a little bit about the real world impacts of these kind of diplomatic changes? The one that really sticks out in my mind is the changes at the Security Council, where the United States has a veto.

FRANÇOISE GERARD Yes. This summer there was a resolution being negotiated on women in armed conflict and what kind of services women in armed conflict need and of course, these mass rapes in a lot of these cases and women need access to sexual and reproductive health services. And the U.S. threatened to veto the resolution if any mention of sexual and reproductive health services stayed in the resolution. And so it was stripped to avoid a U.S. veto. The reason I think the U.S. hasn't been able beyond the Security Council to stop mention of sexual and reproductive health or gender equality is both because there's a lot of work being done on this across the world, but also because the U.S. has not played well with the other kids in the sandbox, if you want. You know, if you come to the United Nations intent on dismantling multilateralism and you object to the climate agreements and you're constantly berating other countries, you're not making friends, and diplomacy is about wielding influence and so you have to mind your relationships. And I have to say, the Trump administration has not done that.

JESSICA GLENZA Probably the best evidence is this recent declaration on universal health care. It was something that was agreed on the United Nations a long time ago, but the United States objected in particular to the phrase “sexual and reproductive health.”

[CLIP]

ALEX AZAR Such terms do not adequately take into account the key role of the family in health and education. [END CLIP]

JESSICA GLENZA Alex Azar, secretary of Health and Human Services, read a statement on behalf of 19 cosigning nations.

[CLIP]

ALEX AZAR Nor the sovereign right of nations to implement health policies according to their national context. There is no international right to an abortion, and these terms should not be used to promote pro-abortion policy. [END CLIP]

FRANÇOISE GERARD Now what they did is they got a number of countries which are not known for their commitment to women's equality in sexual and reproductive health, such as Saudi Arabia and others to line up with them.

[CLIP]

ALEX AZAR Bahrain, Belarus. Brazil. The Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Guatemala, Haiti, Hungary, Iraq, Libya, Mali, Nigeria, Poland, Russia and Yemen. We only support sex education that appreciates the protective role of the family in this education. [END CLIP]

FRANÇOISE GERARD The rest of the governments assembled there and that's more than 190 supported the agenda. And there was a very strong declaration read by the ambassador of the Netherlands on behalf of 58 countries to say this agenda is not negotiable and we're not going back to pre-Cairo times.

SIGRID KAAG Between 5 to 13 percent of maternal deaths every year to the World Health Organization can be attributed to unsafe abortions.

JESSICA GLENZA Sigrid Kaag is the minister of Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation for the Netherlands. She read the statement about sexual and reproductive health at the U.N. last September.

SIGRID KAAG And if you want to work on HIV prevention and treatment, if you want to end female genital mutilation, cutting or end child marriage, all this is tied intrinsically to our ability to provide for sexual rights and reproductive health. It's an important moment for everyone to wake up to. Also, consider that women's rights are really often in other countries the canary in the coal mine.

JESSICA GLENZA As New York City gets ready to host world leaders for the Commission on the Status of Women, this coming week, health advocates like Gerard are bracing for demands from the Trump administration. But even if the language of international agreements stays intact, there are other ways to exert power.

SIGRID KAAG If they can't get their way at the U.N., the U.S. has U.S funding, which is very significant as a cudgel.

JESSICA GLENZA Republican administrations have instituted the so-called Mexico City gag rule since the Reagan administration. Democrats have always reversed it. The gag rule bars any group receiving U.S. State Department aid from counseling women about abortion or for any abortion services whatsoever. But the Trump administration has expanded the policy, attaching it to $9 billion dollars a year in aid that's used for all kinds of health programs overseas. From malaria prevention to nutrition, there are exceptions to the gag rule. It doesn't apply to governments and it doesn't apply to post-abortion care. But Françoise Gerard’s group has been finding that the gag rule is interpreted extremely broadly.

FRANÇOISE GERARD What we find is that it's too complicated, you know, for a lot of the providers on the ground, all they understand is the U.S. does not like us to speak about abortion, if we receive U.S. funding, we should just stop doing anything on abortion, talking about, etc. So it's overapplied and as a result, you have women being turned away from clinics that could help them and you have providers that used to collaborate, you know, to provide comprehensive health care to their communities, basically not talking to each other if one of them is dealing with abortion, fracturing coalitions of organizations on the ground and we've seen that very much in South Africa, for example. So it's very harmful to women's health as well as to civil society and freedom of speech.

JESSICA GLENZA 25 years ago, abortion opponents found themselves on the political outs deported from the UK and losing ground in international agreements. Today with the full force of a presidency behind them, that's no longer the case. As we heard earlier, women's rights are the canary in the coal mine. The U.S. might fail to remove this language from international law, but the attacks telegraph a winning strategy to opponents of human rights around the globe, oppose sexual and reproductive rights, and gain a powerful ally, America. For On the Media, I'm Jessica Glenza.

BOB GARFIELD That's it for this week's show. On the Media is produced by Alana Casanova-Burgess, Micah Loewinger, Leah Feder, and Jon Hanrahan, and Asthaa Chaturvedi and Xandra Ellin. We had more help from Anthony Bansie and Eloise Blondiau and our show was edited by Brooke. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineers this week were Sam Bair and Josh Hahn.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD And I'm Bob Garfield.