Organizing Chaos

( Steve Helber / AP Photo )

BROOKE GLADSTONE From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. From Sorting to Taxonomy. One scientist thought he was ordering the world, but really he was fostering more division.

LULU MILLER There were eugenics fairs at small town festivals where there'd be competitions and there'd be the best babies or the fittest families.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It was so...gross!

LULU MILLER It was so gross!

BROOKE GLADSTONE You know what they say about the path to hell? Also, how librarians are grappling with the legacy systems they use to organize the books on their shelves.

JESS DeCOURCY HINDS Books on Obama were in three hundreds. They were separated from books on other presidents. And that was very disturbing to me. And that was the beginning of changing Dewey, of rebelling against Dewey.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The powers and perils of classification, after this.

[END OF BILLBOARD]

BROOKE GLADSTONE From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. Humans as a species have a fascination with order. We like categories, lists and rankings and labeling them all. In fact, much of science is devoted to sorting the seeming chaos of the natural world. Of course, sometimes we go too far or in the wrong direction by imposing an artificial order based on irrelevant criteria or bias. Last year I spoke with Radiolab co-host Lulu Miller, who was struggling to impose order on her own life when she became obsessed with the 19th and 20th century taxonomist and natural historian David Starr Jordan. Jordan himself was obsessed with cataloging and ordering the world. A hundred years later, that passion earned him a starring role in Miller's book, Why Fish Don't Exist A Story of Lost Love and the Hidden Order of Life.

LULU MILLER There are things that he does, especially when he's a kid that just make you fall in love with him. When he gets bullied, he starts doing things alone, like trying to complete the task of clasping his hands and jump through them. So, like he's just a sweet loner.

BROOKE GLADSTONE His Puritan parents, especially his mother, disapproved of his obsessions and his massive collections.

LULU MILLER Yeah, he sort of woke into the world. He had all these questions about what he saw around him, and so first he started putting names to every star in the sky. He moved on to flowers and he started pinning them to the walls and writing their scientific names underneath them, making topographical maps of every place around him. And at one point, his mom just threw them away.

BROOKE GLADSTONE His entire childhood was bound up in this stuff.

LULU MILLER So much sweaty, sweet, careful labor. And she just thought, this is a waste of time. He should be out on the farm. They were struggling to make, you know, ends meet and she told him to, quote, find something more relevant to do with his time. According to his accounts, taxonomy had sort of had its run. Carl Linnaeus, the famous forefather of taxonomy, had published his Systema on Naturae, which was proposed to be this map of all life, properly arranged about a hundred years before. There was this sense that the world was known. We didn't need to look at it anymore. His neighbors called him shiftless and a ‘waster of time.’ Collecting got sort of a bad rap, and as he grew older, he just still loved doing it. His brother died when he was pretty young, and he had been very close with him. And right after that moment, he just goes back to drawing. And his journals explode with color. He's drawing ivy. He's drawing carrots. He's drawing pine branches like anything he can get his hands on.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Your theory is that he was trying to impose order on chaos.

LULU MILLER Yeah, he talks about this urge even if he can't control the world, at least he had naming. If he could just order the world, there was some sense of agency. I don't want to go overly into like pathologizing, the very human impulse to collect and know our world. But there are some people who've studied obsessive collectors. Often the habit will kick into gear after some sort of major deprivation or tragedy or trauma. Each acquisition floods you with this sense of fantasized omnipotence. Is how this one guy, Werner Muensterberger, puts it that you can kind of become addicted to.

BROOKE GLADSTONE In his early 20s, he is a perpetual student, he's also an educator. He learns about a sort of camp for young natural historians, an island off of Massachusetts called Penikese.

LULU MILLER Yeah, it's this tiny, little horseshoe shaped island, an hour's ride away from the coast. Just horizon on every side of you. Louis Agassiz, the very famous Swiss geologist who by this point was teaching at Harvard, decided that the way that Harvard professors were teaching science was all wrong. They wanted their students to learn to memorize beliefs out of books. And he thought that beliefs were roadblocks, because once you started to believe the beliefs.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You cease to observe.

LULU MILLER Yeah, you would cease to observe. And so he started this camp where he could train the future scientists of America in the right way to do science, which is climbing around in nature, getting dirty, looking at things through microscopes. And that first summer, he put out a call for applications. David Starr Jordan was miserable out at this college in the Midwest. He was advised not to let his students touch microscopes, he was chastised for teaching the Ice Age theory that there had been a time when the earth was covered in ice, and Louis Agassiz was the guy who discovered it - blah, blah, blah. So he applies to this camp, gets in, he's one of 50 students, men and women, all interested in taxonomy. Spends this blissed out summer. He sees phosphorescence for the first time. He's 22 years old and it's the first time he sees the ocean.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And the impact of Louis Agassiz can't be underrated. You wrote about a breakfast benediction that he gave. It went like this: ‘said the master to the youth, we have come in search of truth. Trying with uncertain key, door by door of mystery. We are reaching through his laws to the garment hem of cause. Him, the endless, unbegun, the unnamable, the one. As with fingers of the blind, we are groping here to find what the hieroglyphics mean of the unseen. in the scene.’

LULU MILLER Agassiz literally thought that every single species was a thought of God, and that the work of taxonomy was to arrange those thoughts in their proper order and discover the divine plan of God. And what the divine plan meant was this intricate communication of God's values and how to be in the world, and possibly, if you read it right. The path to further ascension. And so Agassiz called the work of taxonomy missionary work of the highest order. David writes about that morning. He said it was this transformational moment in his life because suddenly he had a response to all the people who said that his hobby was pointless.

BROOKE GLADSTONE He traveled the globe to, quote, discover a new species of fish, catalog them, name them.

LULU MILLER Yeah. He starts collecting for the Smithsonian, he gets promotions, he becomes the president of Indiana University. He'd throw dynamite into the water to unearth fish. He would use harpoons like any method he could think of and poison. He would in tide pools, he came up with this device.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Strychnine, which plays a role later in his story, but we might not get to that. The possibility that he murdered the head of Stanford, but never mind, you became enamored with the idea of David Starr Jordan as a as a symbol of determination.

LULU MILLER Yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE In the face of chaos. He lost his collection multiple times over the course of his life, especially during the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. It was stored at Stanford, a whole of system of order, obliterated. And he and his team are credited with discovering a fifth of the fish species that were then known.

LULU MILLER Yeah, his first collection was struck by lightning and burnt to the ground. I mean, it almost feels like a myth. He thinks he can order the world - chaos says ‘mmm - can you?’ He builds it back up, it takes almost 30 years and an earthquake comes and he loses thousands of fish. They're separated from their names. And it was this moment where he did this gesture – and this gesture is what pulled me into his tale, I didn't even know who he was yet, but I heard this anecdote. And I know it is almost embarrassingly arcane, why did this possess your life for 10 years? Why did you write a book about this guy? But this was the moment he took the fish off the ground and he started the practice of tying the label to the fish, stitching them right into the flesh, as if to say, ‘nature, no matter what you throw at me, I can own you.’ And I thought this is such a metaphor for our species and for our need to know the world and possess it. The refusal to back down from these increasingly clear messages that chaos reigns, that we live in a world that we cannot control.

BROOKE GLADSTONE When you learned darker and darker things about how he conducted his life, he had a shield of optimism, which sounds like something great. But when you break it down, he was really good about lying to himself.

LULU MILLER Yes. A colleague of his said no matter how bad the day, he could always be found a humming a tune down the arcade. But what is that shield comprised of? One of the key ingredients is to believe you're a little better than you actually are. Psychologists have studied this. They call it positive illusions. And it's this idea that if we can lie to ourselves a little bit, you actually see profound benefits in mental health. Even in relationships, it's kind of like a matter of how much delusion, and there is clearly a slippery slope where, you know, you do get social punishment for being too deluded about yourself or your abilities. But there is this weird spot, if you lie a little, it serves you really well.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Right, but he was making judgments that he wasn't capable of making. And like his mentor, Louis Agassiz, he ranked what he found. And like his mentor, he believed bad habits, so to speak, could cause species to devolve, whether in mollusks or in man.

LULU MILLER Yes, when Darwin came along, David Starr Jordan did do away with the idea that there was a divine plan. He did let go of God, but he still believed there was a somewhat divine hierarchy carved by time that more quote unquote complex, if such a thing is even measurable, meant more evolved, not better as well.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Darwin never did that. He never ranked species from ‘complex’ and ‘closer to God’ to ‘degenerate,’ ‘intrinsically evil.’

LULU MILLER Yeah, I mean, Darwin has his sins and he's complicated. But what really shocked me, reading on the Origin of Species and rereading it and reading it with a pen was just how clearly he warns against ranking. Then he says that hierarchies and even categories at all even edges in nature. And this is what really blew my mind, that those are fabrication of the human mind. They're superimposition. They're a proxy.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Edges, what do you mean by edges?

LULU MILLER That there are not hard lines, even between species. One of the things he really hammers is, gets a little technical, but it's cool. One of the things that taxonomists say is that two different species can't create fertile offspring. And he just shows time and time again these examples where actually two different supposed species do create fertile offspring. There aren't the hard lines around species or around genera or going further up the tree phylum even that. That is a human way of parsing the world to feel safer in it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Darwin's disinclination to put species in boxes and especially to rank them did not communicate to Starr. And a turning point for him was when he went to Aosta, a sanctuary city in Italy, a place where for centuries the Catholic Church had provided shelter and food to people who had been rejected by their families because of their disabilities.

LULU MILLER You might see beauty in that town. Here's a place where people have safe harbor and are given the tools to flourish. Or what David saw and he went three times, he called it, quote, a veritable chamber of horrors. People drooling or coming up to him and begging. And he said, you know, this is a subspecies of man. And this is where the whole human race is going, if we don't take action. And he becomes one of the earliest embracers of eugenics.

BROOKE GLADSTONE He thought that the people of a Aosta were literally degenerating into a new species of man. And he called this process animal pauperism.

LULU MILLER Yes. That ‘laziness,’ quote unquote. Basically the bad habits, the bad behaviors can cause not just a person, but a species to sort of reverse evolve to slide down that ladder.

BROOKE GLADSTONE He didn't believe in nurture much at all. It was all about nature for him.

LULU MILLER He actively, in some of his books, he mocks education. He says education can never replace heredity. And he begins to believe that all kinds of traits are linked to the blood. Criminality, poverty, illiteracy, what they call feeble mindedness, that we could reduce all kinds of things by not allowing certain people to continue to live.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Coming up, the conclusion of our interview with Lulu Miller.

LULU MILLER I was spat out near the top of this social hierarchy, I'm queer, so knock me down a little. But I'm a white woman. I'm near the top, and our world is so disorienting and sure that can feel frightening. For me, I just keep thinking about the concept of order as this violent structure and things have to change.

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media.

[BREAK]

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. Continuing our 2020 conversation with Radiolab co-host Lulu Miller, we turn to the dark side of taxonomist David Starr Jordan's fervent effort to bring order to the natural world over a century ago. A fervor that led him to the practice of eugenics, which advocated the deeply disquieting practice of improving our species by encouraging reproduction in some, and suppressing it in others.

LULU MILLER The simplest thought was that you could actually kill people. He didn't think that was humane. So he suggested the idea of sterilization. Single out people he called, quote unquote, unfit. Again, you see him employing scientific jargon to make his beliefs sound like a biological reality. But he starts advocating for these ideas as a great way to heal society into his lectures at Stanford. He talks to this really wealthy widow, Mrs. Harriman, and gets her to donate hundreds of thousands of dollars to start the eugenics record office, which will become a huge player in claiming certain people are unfit based on their criminal records or their hospital records, things like that. He joins political organizations. He's a huge pusher for these ideas. And starting in 1907, the first eugenics law is passed in his one-time stomping ground of Indiana. And it's the very first time in the world that there is forced eugenics, sterilization for someone deemed unfit. He helped get it passed in California. And slowly in the early 1900's more and more states are passing these mandatory eugenics sterilization laws.

BROOKE GLADSTONE This law isn't just the first in the country, it's the first in the world.

LULU MILLER There is resistance. Judges or governors who strike down their state's attempted eugenics law. And there are activists and even scientists calling the ideas behind eugenics, quote unquote, rot. But it did sweep the country. There were these eugenics fairs at small town festivals where they would have a tent, where there'd be competitions among the babies who were sort of weighed and measured like pumpkins, and there'd be the best babies or the fittest families.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It was so…gross!

LULU MILLER It was so gross!

BROOKE GLADSTONE Just deciding what is a desirable characteristic is such a horrible slippery slope. As you mentioned, you spend some time with the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded in Lynchburg, Virginia. In the 20s under Chief Albert Priddy, the center started sterilizing women to cleanse the nation of the subpar, starting with Carrie Buck. At the age of 17, she got raped, she gave birth, then her parents dropped her off on Dr. Priddy's doorstep and he noticed that she looked familiar to another one of his inmates.

LULU MILLER She was the daughter of Emma Buck, who was in the colony under allegations of prostitution and perhaps drug use. Priddy was a passionate eugenicist, he'd sterilized all kinds of people before Carrie, mostly women, for having wanderlust, for passing notes in class. He had been searching for a case that could help him prove what he was doing was, you know, biologically sound. And he realized, OK, well, if she's here, maybe this is proof that, quote unquote, feeble mindedness is heritable, because here we have a woman forced by circumstances to become a prostitute. And here, look, her daughter was raped and therefore I'm judging her promiscuous. All we need to do is test her baby. And then if there's proof of feeblemindedness there, we'll have proof that that really feeblemindedness is heritable over the generations.

And so he had someone from the Eugenics Record Office come out and test this little baby, just a few months old, and, you know, they maybe ran a penny in front of her eyes – it's not clear exactly what tests were run – but that researcher declared the baby feebleminded. A little baby, based on these bunk tests. And this case, the sterilization of Carrie Buck, eventually made it all the way to the Supreme Court in 1927 under this question of can we sterilize a person for the good of the rest of society under this eugenic ideology? And long story short, they voted eight to one in favor of sterilizing her under the idea that three generations of imbeciles is enough.

BROOKE GLADSTONE I was just wondering if this is a good time to mention Hitler.

LULU MILLER Yes. The American movement predated Hitler's movement. Were some of the early posters to pass sterilization in Germany said we do not stand alone. And there was a picture of the American flag. Americans had sterilized thousands of people, and then in 1933, Germany passed the law to allow the sterilization of what would eventually become hundreds of thousands of people and an American eugenicist. Joseph DeJarnette, said the Germans are beating us at our own game. You know, I think these ideas arise from different places. Francis Galton turn coined the term eugenics in England. And, of course, like this idea of bettering a herd on your farm, like that has been around for a long time, so these ideas are coming up from all over. But we were the first to legalize it in the world and to make real headway on these ideas that certain people in society should not be allowed to live. And that that will be better for the rest of us and that there is some kind of ideal to empower and support, and we should get rid of the rest actively.And a lot of these people, Aggasiz, David Starr Jordan, DeJarnette, they're all over buildings. They've statues of them up at academic institutions. And these were people really actively pushing for the genetic death of certain kinds of people.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And so Jordan becomes a cautionary tale about where the drive to impose order on the world can take us. One of the big reveals in your book comes in the title - Fish Don't Exist. Tell me what you meant by that.

LULU MILLER So this is this amazing revelation in the biological community that taxonomists realized in about the 80s, and it goes back to the Darwin thing. That actually the edges in nature are not there. This group of scientists called Kladists came along.

BROOKE GLADSTONE –before you get into it, why are they called Kladists?

LULU MILLER So Cleetus is Greek for Branch. And it is the branches of the tree of Life that they are interested in looking at accurately, not based on this human centric sense of what goes together. You could lumped together anything that has stripes and there'd be zebrafish and zebra and those little furry caterpillars. But that is not a scientifically meaningful category of creatures if you're trying to group things in terms of how they're related. So this is the whole puzzle of taxonomy. How do you decide who is closest to whom? And so around the 80s, the Kladists kind of stumbled across this idea that certain characteristics give you better clues.

So they'd say, you know, look, we got to not be distracted by things like skin or fur. We have to look deeper at the bone structure and the organs. So, they would say, I'm going to hold up an image of a cow, a salmon and a lungfish. Lungfish looks like a pretty fishy fish, scaly tail. Which of these two things are most closely related? And inevitably, a biology student would raise their hand and say, the salmon and the lungfish, you know, they're both fish in water. That's my guess. And then slowly, the Kladist would reveal why this isn't true. And they'd say, well, look, both the lungfish and the cow have lungs. They both have this thing called an epiglottis, which is this little flap of skin that goes over the throat that kind of came along later in time. And they have a more similarly structured heart. You can't deny that actually, a cow and a lungfish are more closely related to one another than a lungfish and a salmon. And what that means is that, OK, you know, if you want to keep fish together, you'd have to include a cow in there and a human and a bird. You could keep all fish together, but then it's more like the word vertebrate, like it's so broad that actually the more scientifically sound thing to do is admit that fish is not a legitimate grouping of creatures that aren't actually close. And you can see it's very naturally carved out by the water. You know, we just think there they have these tails and they have these fins and so they're all fish. But that is obscuring a greater truth that there are things down there that are more closely related to us than to one another.

I learned this concept as I was researching Jordan, and it completely blew my mind. And it was this like violently counter intuitive thought. I have a sense that it matters that this isn't just a nerdy linguistic party trick. Fish don't exist. Yeah, they do. Then I set out to try to understand that. I titled the book that I know people get annoyed, they roll their eyes, fish don't exist, but my sincere hope is that you emerge from this story not only understanding and hopefully believing that idea, but carrying it around with you as a reminder to have more doubt in all categories around you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE One dismaying conclusion you came to, dismaying and wonderful, is that if you're a Kladist, you are far less inclined to other creatures if, using other as a verb there, and especially you talk about fish, some of whom have memory senses of humor. Pescatarians are out of luck.

LULU MILLER Yeah, I think it's about having a real vibrant curiosity about anything. You know about any, any category you're making. Whether it's in fish or whether it's in a type of student that you're not accepting to your institution. These eugenic sterilization laws that just kind of soberly allowed for the violent cutting off of your chance to carry on, you know, just because we say this word unfit that we think we have a grasp on and there are still laws on the books that now use slightly different terms, like incompetent or unable to give informed consent or lacks mental capacity that allow for the mandatory sterilization of people. And are we so sure we're okay about that? Who is hiding under that language? Why fish don't exist? Is this absurd French surrealist painting? This is not a pipe kind of thing. But my hope is that what that does is to remind you that, like, we are bad at carving up our world, the work of being a good human is to keep real vigilant curiosity about the creatures trapped underneath our categories.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And even harder, it seems to accomplish, is to let go of your intuition.

LULU MILLER Yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And you wrote that seeing the world, or trying to, without intuition, I mean, we can't obviously let it all go, was a peculiarly marvelous feeling.

LULU MILLER Yeah. And it's hard. What do we have in the dark, but our intuition to guide us. I suck at it, most days. Most moments.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Can you find that place in the end of the book or one of them where you write about going into nature and being really conscious of...

LULU MILLER Of what I don't know?

BROOKE GLADSTONE ...not doing what we are all wired to do.

LULU MILLER Yeah. Let me find one. [BRUSHES THROUGH PAGES] OK, I think. OK. How about this? So this is in the epilogue. ‘When I give up the fish, I get a skeleton key. A fish shaped skeleton key that pops the grid of rules off this world and lets you step through to a wilder place. The other world within this one. The gridless place out the window where fish don't exist, and diamonds rain from the sky, and each and every dandelion is reverberating with possibility. To turn that key, all you have to do is stay wary of words. If fish don't exist, what else do we have wrong?’

BROOKE GLADSTONE Despite the fact that science stands with Kladists, with regard to the existence of fish, nobody wants to go there.

LULU MILLER Yeah

BROOKE GLADSTONE It is just not catching on. Obviously, intuition is just implacably strong. But could you tell me some of the marvels you encountered when you are able to let it go? I mean, you describe in the book a lifelong existential ailment.

LULU MILLER Yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And suppressing that intuition seemed to be a means of dealing with it.

LULU MILLER Yeah, I do think with intuition comes the certainty of, you know, what's good for you, You know what you're bad at, You know what's scary. All these things. And when you can just suppress it a little and say, maybe, but let's go investigate. I have continued to be wowed by surprises and things that existed outside of my intuition or my certainty. One of the biggest marvels was meeting my now wife and still thinking she's younger than me. She's shorter than me. She's a girl. That's not what keeps me safe. That's not what is a mate. You know, these kind of silly criteria, took a second to let go of. I mean, it was mostly guided by how freaking delightful she is to be around and how fun she makes the world. But I think there was a little bit of all this research in there because I met her toward the end of writing this. And I think she was this huge, clear gift of what you can welcome in when you do that. That's an obvious one but then even just the little things.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The past several months have offered lots of chances to let go of preconceived notions of what's what. You started to see order its self as a kind of violence.

LULU MILLER Yeah, the word itself order, ordin em, comes from the Latin for loom, which is arranging of threads neatly in a loom. And then that became to be used metaphorically as the way that people sit under the ranks of a king or an army general. Order itself, you know, it is based on the discounting of certain qualities within people to make them fit in this unnatural form on the loom. I think that with all the rebellion and the unrest, it's like people who have been trapped for so long under this violent order and no one has been listening. Look, I was I was spat out near the top of this social hierarchy. I'm queer, so knocked me down a little. But I'm a white woman. I'm near the top, and our world is so disorienting and sure that can feel frightening. But it is this moment for me. I just keep thinking about the concept of order as this violent structure and things have to change.

BROOKE GLADSTONE What is the most revelatory order-overthrowing thing that you learned about a fish?

LULU MILLER They've done these studies that show that that they will actively seek out the soothing, of either the touch of another fish or sometimes even the touch of a human hand that they've grown comfortable with. And that like us, when they are afraid, when they are in some kind of physical pain. There is this strange power in being held and that like it's not some whiz banging, they can memorize 10000 places, which they can also do. They have incredible cognitive skills. But there was something, so there's more similarity down there. There's more difference, too. But just that there's more nuance. There are more unexpected qualities down there, so that, yeah, that's the one for some reason that being with another being helps them.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Wow. Lulu, thank you so much.

LULU MILLER Yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE We spoke with Lulu last year just before the election, when chaos did indeed loom large. She's the co-host of Radiolab and author of Why Fish Don't Exist A Story of Lost Love and the Hidden Order of Life. Coming up, lessons from a place where classification is a big deal, the world of libraries.

[CLIP]

DIANE BLACK Can you believe that the Library of Congress would make a decision, with a bunch of liberal students from Dartmouth University who sent a petition to them to say that this was a dehumanizing or an inflammatory term. And to make that decision on political correctness to change something that has been in the lexicon there at our Library of Congress since back in the early 1900s is just unbelievable to me. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media.

[BREAK]

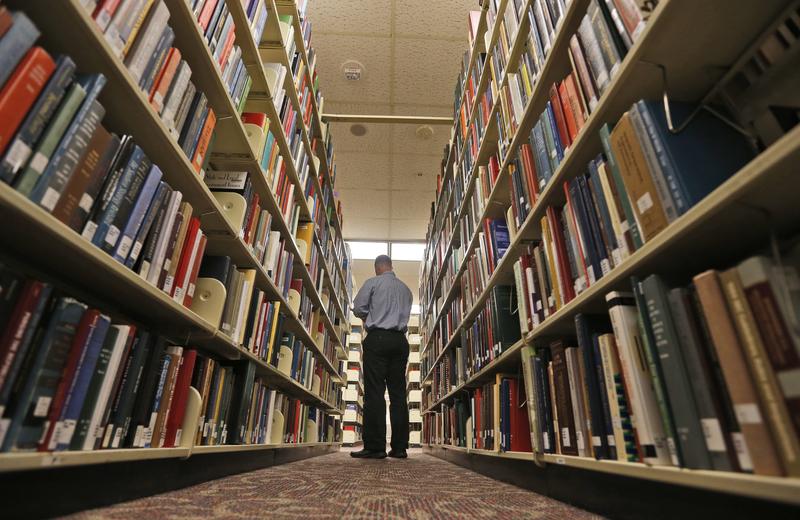

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. Lulu Miller explains the perils and limitations of imposing order on the world. Order, codes, and standards can make the world seem to function more comprehensively and efficiently. Like the standards for the electric current that runs through the walls or the Internet standards that let us send messages back and forth, or the credit card standards that allow us to pay with a swipe of plastic. All these can make navigating the world seem a whole lot easier, but they're also centers of power. On the Media producer, Molly Schwartz brings us the story of how power has become entrenched quietly through standards in a quiet place: the library.

JESS DeCOURCY HINDS So I've been there 12 years,.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Jess DeCourcy Hinds is a writer and the director of the Bard High School, Early College, Queens Library.

JESS DeCOURCY HINDS I founded it. I started it from the ground up.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ As the solo librarian. She has to do everything herself, including catalog all the books using the Dewey Decimal System.

JESS DeCOURCY HINDS We librarians who work with Dewey are well versed in these numbers.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ For all the librarians out there, a quick primer on the Dewey Decimal System:.

[CLIP].

[MUSIC PLAYS]

NARRATOR Have you ever watched the way others use the library? There's quite a difference in the way they go about it.

[MUSIC CONTINUES UNDER]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ It's organized into ten main classes of knowledge with each class represented by numbers. Philosophy and psychology are the 100s, the 200s are religion. Social sciences are in the 300s. The 400s are language, and the 500s are science. Catalogers can add more numbers to make a deweys no more specific to the book it's describing.

NARRATOR Each figure in the number is significant. 510 tells us the books deal with mathematics. 520 tells us the books deal with astronomy. 530 is physics

MOLLY SCHWARTZ ...and rounding up attending classes are technology, arts and recreation, literature, history and computer science and other information. It's a hierarchical structure in which all of these classes have nearly endless permutations.

NARRATOR You'll be looking for many books in the 800s. You know what they are?

STUDENT Literature.

NARRATOR That's right. 810s are American literature. 820s are English literature. [CLIP ENDS]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ One day in 2010, the Bard High School Early College Library received a large order of books about the civil rights movement, which Jess DeCourcy Hinds was excited about because...

JESS DeCOURCY HINDS Our history section was feeling very white.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ But when this big order of civil rights books came in, she noticed they weren't classified under history in the 900s, but under the 300s...

JESS DeCOURCY HINDS The 300s are a grab bag of books.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ They include everything from anthropology and sociology, labor studies, political science and folklore, but also some books that could possibly be classified in the 900s – the history section.

JESS DeCOURCY HINDS Books on Obama were in three hundreds. They were separated from books on other presidents and that was very disturbing to me. And I just didn't understand why our current president was not going to be part of history.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ And Obama wasn't the only one stuffed in the 300s.

JESS DeCOURCY HINDS . And then when it came to the LGBTQ books and the women's history books and books on immigrant history, all of those were in the 300s as well. And I realized that women, immigrants and people of color were all being pigeonholed in this very strange 300 section. So we just started moving them.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ She and her student interns decided to put President Obama where they thought he belonged – in the 900s, next to the other presidents.

JESS DeCOURCY HINDS And that was the beginning of changing Dewey, of rebelling against Dewey. DeCourcy Hinds wrote about her frustrations with Dewey in a New York Times essay called 'Oh Dewey, Where Would You Put Me?' There have been critiques of Melville Dewey and his system dating back to the early 1900s and recently some libraries have been ditching Dewey in favor of bookstore style organization.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Public libraries are rolling out a new system where books are now organized by categories such as animals or computers.

JESS DeCOURCY HINDS People don't come in and go, 'I feel like an 811 today, no, they think I want poetry.'.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT The Greenwood Public Library is ditching Dewey for a shelf system they call subject savvy [END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ For most of the Dewey Decimal Systems 145 years in use, Melville Dewey has been celebrated as a kind of founding father of American librarianship.

WAYNE WEIGAND We're always searching for heroes. And Dewey was a early library pioneer whose influence was very wide.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Wayne Wiegand is a library historian and the author of Irrepressible Reformer, A Biography of Melville Dewey. He describes how Melville Dewey created the Dewey Decimal System in the early 1970s when he was a student at Amherst College.

WAYNE WEIGAND The Amherst College campus between 1870 and 1874 was a very white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant, male dominated world. Dewey pretty much programed into his system the priorities of courts, which brought also the biases and the prejudices of that world into his classification scheme. You can tell this very easily in the 200s and the religions which heavily privileges Protestantism against all other kinds of religion.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ In fact, nine tenths of the 200s are dedicated to Christianity. Like David Starr Jordan, who Lulu Miller wrote about in her book, Melville Dewey was a late 19th century eccentric who loved to classify things. In fact, the lives of Melville, Dewey and David Starr Jordan have some other eerie parallels. They were both born into strict Protestant households in upstate New York in 1851, and they both died in 1931. And Dewey also had views that made him, if not an outright eugenicist, at least eugenics adjacent.

WAYNE WEIGAND He was certainly sympathetic with the ideas that the eugenicists put forth. He did not see black people as equal to white people. He did not see Jewish people as equal to white people.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Books by black authors were classified in Dewey under slavery or colonization. Even a book of poems by James Weldon Johnson, a famous black writer. When LGBTQ topics get Dewey numbers in the 1930s, they're categorized as abnormal psychology, perversion, derangement and medical disorders.

EMILY DRABINSKY That system will reflect the ideology of the people who designed it.

JESS DeCOURCY HINDS Emily Drabinsky is the interim chief librarian of the Mina Rees Library at CUNY.

EMILY DRABINSKY You can add new language and revise old language, but essentially you are always putting a new item into a preexisting system.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ The Dewey Decimal System is like the original YouTube algorithm. Its power comes from the fact that it groups books next to other books on related subjects so that when you're browsing the shelves, you're basically recommended other books you might like. Dewey wasn't the first person to think of this idea, but he was a brilliant businessman who found himself in the right place at the right time.

WAYNE WEIGAND Andrew Carnegie was donating millions of dollars to put up thousands of public libraries across the country, and it was a rare community that did not have a public library by 1920.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ And Dewey was poised to supply them with an organizational system and an army of librarians to implement it.

WAYNE WEIGAND And his scheme was there and it was being promoted by his students and the library press, and the library organizations.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ For Dewey, his classification was always meant to organize all the knowledge in the world. But of course, times change. New technology gets invented, cultural norms evolve, geopolitics shift. So the Dewey Decimal System is regularly revised. For a long time, those revisions happened within a kind of black box, but according to Caroline Saccucci, who works at the Library of Congress, where she spent 9 years as the Dewey program manager, it's become more Democratic over time.

CAROLINE SACCUCCI A lot of work has been done to really promote this community engagement aspect for the Dewey classification, which I think can only make it better and make it stronger and have community members take ownership of it as well.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Since 2019, proposed doing revisions are posted online and open to public comment. Librarians can even contribute to a numbers back into the system. And of course, an especially frustrated librarian can always just go rogue.

CAROLINE SACCUCCI There's no library police that can come out and tell the library they've done it wrong. Libraries are always free to arrange materials according to the way they want them, and the will best serve their users.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ But that's easier said than done.

CAROLINE SACCUCCI Any time there's a major change to a classification system, it could wreak havoc with the collection because that means that all the bibliographic workers have to be changed. But then all the physical items have to be relabeled and then be shelved, and then signage has to change. And I mean, there's just a whole lot that has to happen in order to reclassify large swaths of material.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Aside from Dewey, there are other library classification systems, including the Library of Congress classification system. It's one of the other largest systems in the world, and it's the brainchild of another white man that's beset with some of the same problems as Dewey.

CAROLINE SACCUCCI The Library of Congress classification system comes from Thomas Jefferson's collection of materials. The Library of Congress. The initial collection for Congress burns down. Jefferson makes a donation to the state of his personal collection, and the classification reflects his original order for his own materials.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Instead of using numbers to classify books, the Library of Congress system uses subject headings. And in 2014, a student at Dartmouth College named Melissa Padilla was doing a research project on undocumented youth organizing. She went to meet with Jill Barron, a Dartmouth librarian, to find resources, and they noticed a subject heading that Melissa found disturbing.

[CLIP]

JILL BARRON There were pages and pages of variations on the term illegal aliens. This was the term had been used to categorize this particular book. [END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ That's Jill Barron in the documentary Changed the subject. A group of Dartmouth students protested the use of the term illegal alien, but they discovered that the problem wasn't with Dartmouth.

[CLIP]

STUDENT We didn't realize that it was like a national database that applied to like every institution. It was in some ways our naive understanding of systems, [END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ so the students filed a petition with the Library of Congress to change the subject heading and the revision was accepted. But this was 2016, a year when the question of immigration was at the center of a contentious presidential race. Republican members of Congress got wind of the proposed change and decided to block it.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Cruz, one of four Republican lawmakers, to sign a letter urging the Library of Congress not to eliminate the term illegal aliens from search terms and cataloging. [END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Here's Diane Black, a then congressional representative from Tennessee.

[CLIP]

DIANE BLACK Well, can you believe that the Library of Congress would make a decision with a bunch of liberal students from Dartmouth University who sent a petition to them to say that this was a dehumanizing or an inflammatory term. And to make that decision on political correctness to change something that has been in the lexicon there at our Library of Congress since back in the early 1900s is just unbelievable to me. [END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ The change was successfully blocked. And to this day, illegal alien is still an official term in the Library of Congress subject headings. But the incident breathed new life into a movement among librarians who want to reform cataloging. Even when that requires working through slow moving bureaucracies

EMILY DRABINSKY is it's an intellectual infrastructure.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Emily Drabinsky.

EMILY DRABINSKY Most people don't even know it exists, much less get exercised about it. It's an incredibly difficult ship to maneuver.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ In 2013, Drabinsky published an article called Queering the Catalog: Queer Theory in the Politics of Correction. She considers herself part of a group of so-called critical catalogers. But libraries, with their committees and careful processes, are a poor match for the speed at which cultures change and evolve.

EMILY DRABINSKY You have a system that cannot keep up with the rapidly changing language that LGBTQ plus people use to describe themselves. So that you'll have remnants of old language, and that will be the only language that's there. So gay men, lesbian, but there are many, many other words for people in the contemporary moment and none of them are in the system. The language is never right. It's never correct, because it's always delayed. If language could even be correct in the first place, which I think it probably can't.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ She points out that in the Library of Congress classification system, the one her library uses, the problem isn't only how things are named, but that some things aren't named at all.

EMILY DRABINSKY Another example of how bias is in the system is I want to look up African-American women's history. I do a search and it comes up. What if I wanted to do research into the history of white women? White is an unmarked category. It doesn't even appear it's impossible to retrieve. So the normal is not named at all.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ For decades, proponents of critical cataloging have been showing the ways that library classification reflects systems of power that are at play outside the library walls and also reinforces them. Some librarians critical of classification systems want to burn them all down and start over, but they're not in the majority.

EMILY DRABINSKY I always wonder when people say burn it down if they've ever built anything, it can be very, very difficult to build things. The interoperability piece is super important, and if we want libraries to be able to share, we need those systems to continue functioning.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Part of the reason classification is so problematic is because it's inherently reductive. Numbers and language are always flattening the thing they're trying to describe. Shrinking big ideas into small codes that can fit on the spine of a book. Talking to library catalogers, I realized this isn't an exact science. It's a craft. One that's at bottom about making sure we have access to the ideas of others.

EMILY DRABINSKY The most magical thing that libraries do is share. I use OCLC, and my records are there. And then I have colleagues on the other side of the planet who are using those same systems as well. And it means that we can go back and forth borrowing and lending between each other. So that interoperability is really important.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ In a world without order, our classification systems will always be imperfect approximations. So even if, as Lulu Miller says, fish don't exist, the Dewey decimal number for books about fish is 597, and if you go to that spot on the shelf in your local library, you might learn a thing or two about creatures that live underwater. For On the Media, I'm Molly Schwartz.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And that's the show. On the Media is produced by Leah Feder, Micahl Loewinger, Eloise Blondiau, Rebecca Clark-Callender and Molly Schwartz. Xandra Ellin writes our unique newsletter. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media, is a production of WNYC Studios. I'm Brooke Gladstone.