Lock Him Up?

( Department of Justice / AP Photo )

NEWS REPORT We shouldn't desire that an ex-President be prosecuted. This would result in crisis no matter what.

ILYA MARRITZ From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. On this week's show, as the legal troubles of Donald Trump continue to mount, a bigger question about whether presidents ever should be prosecuted permeates the media.

RICK PERLSTEIN It's the too big to fail theory of the presidency.

ILYA MARRITZ But in other democracies, ex leaders are routinely brought to trial and even jailed.

JAMES D. LONG Five former leaders that are being prosecuted. So you'd think that that would really lead people to not believe in democracy, but South Korea has actually survived it very well.

ILYA MARRITZ And sometimes they even come back.

RACHEL DONADIO Italy with Berlusconi does show that you can be under investigation, on trial, even convicted, and then still keep bouncing back politically if there is not a clear opposition.

ILYA MARRITZ Plus, media wags are reading the tea leaves to divine what's going on at CNN. It's all coming up after this.

[END OF BILLBOARD]

ILYA MARRITZ From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. Brooke Gladstone is out this week. I'm Ilya Marritz. You might have heard me as a guest on this show a few months ago talking with Brooke about the podcast series I hosted with Andrea Bernstein called Will Be Wild, all about the attack on the Capitol on January 6th, 2021. Before that, I worked at WNYC co-hosting another podcast with Andrea called Trump Inc, in which we and journalists from ProPublica investigated the former president's business dealings. So when the producers asked me if there were any stories I had in mind for this week's show, I pitched a Trump story.

[CLIP MONTAGE]

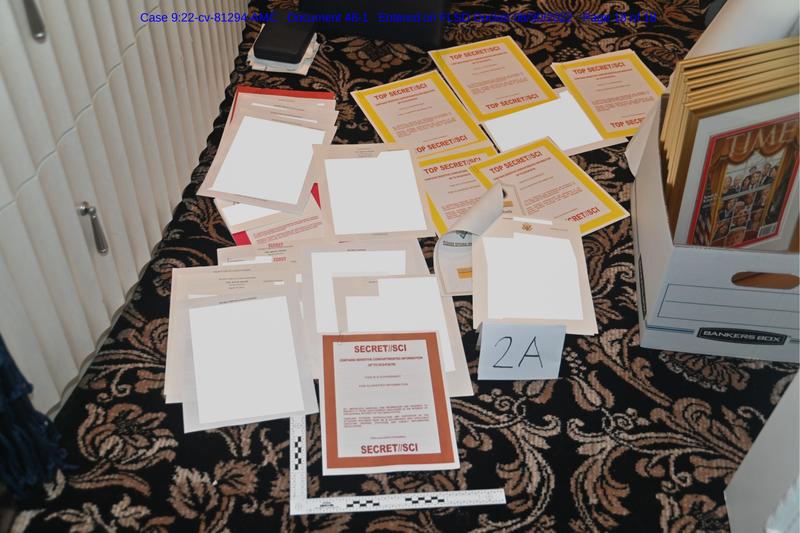

NEWS REPORT And we begin this hour with the latest fallout from the FBI's execution of a search warrant at former President Trump's Mar a Lago home.

NEWS REPORT Justice Department officials say government documents were, quote, likely concealed and removed from a storage closet in an effort to obstruct their investigation into the former president.

NEWS REPORT The Washington Post reports that some of the classified material seized included nuclear intelligence on a foreign government. [END CLIP]

ILYA MARRITZ Well, sort of a Trump story after Mar a Lago was searched in August. The US Department of Justice started presenting evidence, lots of it, of potential crimes around what it said was the mishandling of sensitive government documents. Trump denies any wrongdoing, but for the first time, we're seeing the clear outlines of a possible case against the former president. And with it, an old idea has resurfaced. Adapted for the present zeitgeist. America does not prosecute its presidents.

[CLIP MONTAGE]

NEWS REPORT We shouldn't desire that an Ex-President be prosecuted. This would result in crisis no matter what.

NEWS REPORT Is a DOJ prosecution of a former president worth the risk of the extreme response that could result from Republicans and Trump supporters?

NEWS REPORT Ron DeSantis, the governor, tweeting this out in response. The raid on Mar a Lago, another escalation in the weaponization of federal agencies against the regime's political opponents. [END CLIP]

ILYA MARRITZ DeSantis also tweeted Banana Republic. Perhaps or, maybe not. Seeking accountability for ex-presidents is just another form of American exceptionalism. Consider this according to a study by political scientist John Tours, over roughly the last 50 years, there were 243 indictments of current and former world leaders by their own governments. Many of those countries were not banana republics. They were democracies. James D. Long is an associate professor of political science at the University of Washington. He coauthored an article for the online journal The Conversation titled Prosecuting a President Is Divisive and Sometimes Destabilizing. Here's why many countries do it anyway. James, welcome to the show.

JAMES D. LONG Thank you.

ILYA MARRITZ Let's start with France. Two former presidents there have been charged with crimes. One of them, Nicolas Sarkozy, was investigated in 2014.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Nicolas Sarkozy, the former president of France, has been found guilty in a corruption and influence peddling trial here in Paris. [END CLIP]

ILYA MARRITZ He was tried twice on a variety of different charges. What's been the effect on the cohesion of the country as a democracy?

JAMES D. LONG Democracy is as stable in France, probably as stable as it was before the allegations against Sarkozy. And there's no indication that the investigation against him and its prosecution and even, you know, being found guilty is going to destabilize democracy at the system level.

ILYA MARRITZ How about South Korea?

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Today, a court in Seoul will deliver its verdict on the disgraced former president Park Geun-hye over the massive corruption and power abuse scandal that led to her ouster last year. [END CLIP]

ILYA MARRITZ Five former leaders have been charged with crimes there since the 1990's. That's an extraordinary number.

JAMES D. LONG You'd think that that would really lead people to not believe in democracy or want to try something else or just think that democracies are hopelessly corrupt. And there's no way around that, but South Korea has actually survived it very well and continues to be a democracy. And in the most recent leaders that it's had have not been investigated for corruption. So you could say actually going after former leaders had a deterrent effect. And rather than lead to disaffection or disengagement among the public, what it actually led to were leaders that were less likely to commit crimes or corrupt acts going forward.

ILYA MARRITZ Let's talk about Brazil. Tell me about the case of the former president there, Luis Inacio Lula da Silva. He was jailed in 2018 for accepting bribes. Now he is a leading contender for president of Brazil.

JAMES D. LONG Yeah, I believe his conviction was overturned by the courts. One of the things you could say is, unlike South Korea, where prosecuting leaders really showed the ability for the rule of law and the judiciary to flex its muscle and keep legislators and executives in control. I think what's happening in Brazil is the investigations revealed so much corruption that then that tainted as well the prosecutors and the judges that were involved, and then they were seen as also playing a lot of political games simply in terms of the prosecutions. And that it's led to this sort of cycling of when a certain type of judge is in power, a certain president. You know, the light is shine on them, then it's somebody else and it's somebody else. And everyone's kind of been tainted by it. And now you can sort of imagine Lula da Silva, who just a few years ago it seemed like, you know, he didn't have a future in politics, he was in jail, is now the leading contender to be elected president again.

And so, you know, Brazilians probably either believe that there's going to be allegations of corruption against every elected official and public official, no matter what, no matter whether it's true or they really are all corrupt. And that's what's true. And so they look the same to the common person just looking at the situation. But they could reveal two different things about a political system.

ILYA MARRITZ Now, there are a number of countries that have taken kind of the opposite of the Brazilian approach and basically said, for the sake of continuity and stability, we're not going to do prosecutions. Mexico for many years was one of those where one party dominated politics and presidents were not charged with crimes. That's changed a little bit recently. Also, South Africa, when they transitioned away from apartheid, kind of prioritized continuity and stability over accountability or justice.

JAMES D. LONG One of the distinguishing features that we want to make on our piece is precisely this question of older democracies like France and South Korea and the United States that have had a robust judiciaries and procedures around, you know, prosecutions for many, many years versus those that are just beginning to democratize or at those early stages, because you can imagine the human rights abuses and all of the corruption that goes around a dictator. If they were to democratize, they reasonably fear that that new system is going to prosecute them for their previous crimes. So social science evidence shows that actually it is better for the long term prospects of democratization to not have overzealous prosecutions in that transition moment, and rather to allow there to be, for lack of a better word, some level of impunity or forgiveness, depending on how you look at it.

ILYA MARRITZ And I should say that former South African President Jacob Zuma is expected to be tried for money laundering next year. So maybe that's a sign that South Africa's democracy has matured to the point where a trial like that would not be massively disruptive to the body politic.

JAMES D. LONG The judiciary is famously independent in South Africa. They have definitely not just rolled over for Zuma up until this point, and they've tried to exercise a lot of independence from the other branches of government. And I do think that regardless of what you think about the specifics of the allegations against Zuma, the way the process is playing itself out does suggest that only 25 years later, South Africa is showing a lot of democratic muscle in its ability to competently investigate and potentially prosecute an ex-leader.

ILYA MARRITZ What surprised you when you started looking at all these other democracies that have tried their leaders?

JAMES D. LONG Well, I think one thing that did surprise me, or I didn't realize it until we sort of put two and two together, which is how common it is now. And I think the fact that it's happening in young and old democracies, it's happening in African and Asian and European and Latin American democracies, I think is a good thing because it sets a demonstration effect and says that this is the type of thing that countries with democracy as new as South Africa can pursue, as well as democracies that are older like France. It's good in a democracy to occasionally kick the tires and try to figure out, okay, well, where are their weaknesses? What's funny is, on the one hand, as social scientists, we want to be able to draw conclusions around a whole series of cases and kind of come up with some general lessons at the same time that each one of these individual politicians and the political institutions in which they operate and the legal frameworks that shape how they might be investigated are really distinct and contextually important. And so it can often be hard then to draw conclusions between these cases other than to say, look, these two countries have both prosecuted former leaders.

ILYA MARRITZ James, thank you so much for joining us.

JAMES D. LONG Thank you.

ILYA MARRITZ James D. Long is an associate professor of political science at the University of Washington. Coming up, sometimes when the leader of a country is on trial, the media are, too. This is On the media.

[BREAK]

ILYA MARRITZ This is On the Media, I'm Ilya Marritz, filling in this week for Brooke Gladstone. This hour, what it means when democracies charge their former leaders with crimes. Next up: Italy.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT A grim faced Silvio Berlusconi in Sicily today after hearing that he's been summoned to stand trial in April.

NEWS REPORT Italy's former prime minister stands accused of bribing his British tax lawyer, David Mills, to give false testimony in court. Berlusconi is a defendant in three other trials, one, the sex with an underage prostitute, an abuse of power, another for tax fraud, and a third for violating official secrets. [END CLIP]

ILYA MARRITZ Silvio Berlusconi has faced a string of trials over his decades as a public figure in Italy. But Rachel Donadio, a contributing writer for The Atlantic and former Rome bureau chief for The New York Times, says it's Italy's experience with trying Berlusconi for crimes relating to his business and personal life. That's instructive.

RACHEL DONADIO Berlusconi is a great lesson in the survival of a politician, in spite of repeated prosecution and trials against him. He managed always to turn this around so that he was seen as under attack, hounded and persecuted by left wing magistrates who were on a witch hunt. That was his strategy. He once compared himself to Jesus Christ. He said, I'm the Jesus Christ of politics. I'm a patient victim. I bear everything.

[ILYA LAUGHS]

RACHEL DONADIO I sacrifice myself for everyone. And for a while that worked. Italians have a very dim view of their justice system, much more so than Americans have of our justice system. And that is in part because trials take forever. The justice system is very slow. And so the average Italian has probably had bad experiences with the justice system. Because if you don't know whether a civil case will end in your lifetime, it's not a great investment environment. So I think that he also had some consensus because Italians could relate to the fact that they didn't really think the system was working terribly well.

ILYA MARRITZ So Berlusconi styled himself as a victim, the target of these overzealous prosecutors. But were there ways in which the Italian media's coverage of Berlusconi's trials played in to that polarization?

RACHEL DONADIO There were so many trials over so many years. I think that the ones that were about his businesses and tax fraud and bribing judges and things like that were a little bit technical and difficult for a lot of people to follow. Those were covered in the print media, also a little bit on radio and TV, but it's hard to get into the details. They're really complicated. When the sex scandals came about starting in 2009, that coverage was led by a center left paper, La Repubblica. And in 2009, Berlusconi's then wife announced in that paper that she was filing for divorce. So this contributed to a sense that it was like a left wing attack against Berlusconi. But you also have to bear in mind that the Italian ruling class and the non left wing establishment really only openly criticized Berlusconi when the coast was clear. And there was a sense that that government in 2011 was really going to fall because of the economic concerns, because Italy's borrowing costs were rising. It's really a country where you just don't stick your neck out until you're sure that the person you're criticizing isn't going to turn out to be your next boss, basically.

ILYA MARRITZ You wrote in a piece for The Atlantic, quote, While, ordinary people didn't have the time or interest to follow Berlusconi's legal tangles. The press has become obsessed with them, so much so that it lost track or maybe never had any interest in covering the country's underlying problems: the economy, unemployment, financial insecurity.

RACHEL DONADIO I think that for many decades in the United States, there was a sense that the mainstream media was doing its job to uphold institutions and that the truth should come to light and that that's good for democracy. I think that in Italy there was always a sense of, well, if someone's investigating, it must be because that media is owned by one business person who's trying to attack the other business person. And the investigation was motivated by that. So there was a huge amount of trust in the media then, and I think there's probably less so now. In the years when there was all the coverage of the bunga bunga. Those were also years when youth unemployment was soaring and funny stories about 'haha Italians are living at home until the age of 35.' You know, it turns out that a lot of other countries have giant problems like this, where young people born after 1980 felt shut out of their futures. And that was something that was a huge issue in Italy and wasn't getting a lot of attention in the years when the bunga bunga was getting attention. And I think that that's very much a cautionary tale for the media in the United States, too.

ILYA MARRITZ There's an argument being made in the United States right now among those who want to see Trump prosecuted that we need a robust system of justice that fully upholds the idea that no man is above the law, including a former president. And what I hear you saying is prosecuting former leaders is not by itself a tonic, and political systems don't heal themselves even when the justice system is allowed to run its course.

RACHEL DONADIO Italy with Berlusconi does show that you can be under investigation and on trial and even convicted and then still keep bouncing back politically if there is not a clear opposition, or if your own party isn't able to get out from under your shadow. If the center right in Italy had been able to have any life force of its own without the support or patronage of Berlusconi, then politics would look a lot different. Berlusconi was almost like the patron in chief. It's a very much a kind of a patronage society. And Italians are very attuned to power politics. Who is in charge? Who do I need to be nice to? You know, who does my life depend on in a way? And so, you know, if he's seen as somehow making things possible for a lot of people in spite of the trials, then he's still going to have staying power.

ILYA MARRITZ Does that make him like kind of a kingmaker in politics?

RACHEL DONADIO He's still something of a kingmaker. His sports Italia party has single digits in the polls, but it will be enough to help get the right wing elected into power in the Italian elections later this month. And that would mean that he would have to get something in return, possibly president of the Senate. Unclear, but he's still around.

ILYA MARRITZ Rachel Donadio is a contributing writer for The Atlantic. Rachel, thank you so much.

RACHEL DONADIO Thanks so much for having me.

ILYA MARRITZ Silvio Berlusconi faced plenty of charges after he left office. What happens, though, when you have a leader who is charged with abuse of power? While he's still on the job?

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu appeared in the Jerusalem court this morning as the opening stages of his corruption trial got underway.

NEWS REPORT The trial centers around three cases, case 1000, in which he is said to have received a continuous supply of champagne and cigars from two businessmen. In return, it said he acted for the benefit of one of the businessmen. Case 2000 involves positive coverage from a media tycoon. In return, it's alleged Mr. Netanyahu offered to restrict the circulation of a rival paper and case 4000. The most serious, it's alleged that he promoted regulatory decisions that favored a telecoms company. [END CLIP]

ILYA MARRITZ According to Yael Friedson, the legal and Jerusalem affairs correspondent for Haaretz, Israel has been here before.

YAEL FRIEDSON It's not something to be proud about, but there were quite a few. But I think I would refer to two top cases, the former president, Moshe Katsav, who was convicted of rape. And Ehud Olmert, who was the former prime minister before Benjamin Netanyahu, who was convicted for bribery. Both of them were in jail for that.

ILYA MARRITZ What effect did it have on the Israeli public?

YAEL FRIEDSON Well, in the case of Katsav, since it was rape, it was more an embarrassment. He was like the first president going on trial. When it came to Ehud Olmert. His reaction was totally different from Benjamin Netanyahu. Once the attorney had announced that they are going to file against him, he signed out of office. Benjamin Netanyahu was fighting it. He didn't think he needed to resign. And he's out of office only because there were elections in Israel. And actually it's causing a major political problem because there are many parties who refuse to sit in a government under a politician who has an ongoing trial.

ILYA MARRITZ I know that you've been attending Netanyahu's recent trials. I believe you may have been in court today. We're recording this on a Wednesday, is that right?

YAEL FRIEDSON Yeah. Yeah. First of all, Benjamin Netanyahu hardly ever comes to the hearing. He comes only to major witnesses and only the beginning. And his attitude is that it's nothing of his business. You know, let the lawyers do the job. I was covering Ehud Olmert's trial. He came to every hearing. He was really involved. When Netanyahu comes to court. He makes sure that he won't be photographed while he's sitting down. He always stands up.

JAMES D. LONG Why is that?

YAEL FRIEDSON Because he doesn't want to look as if he's sitting for his trial. He's just someone who comes to court, but it doesn't have to do with him.

ILYA MARRITZ And what's it been like for you? Just being in the room when that happens.

YAEL FRIEDSON First of all, it's weird because as a journalist, I covered him for many years. I used to see him in press conferences. I've seen him with Obama. I've seen him with Trump. I've seen him in many different situations. And it's really weird to see him in court like everyone else. I have to say that. Also very intense because his supporters come to court and they're actually following photographing the journalists who are covering. It's like you need a look around who might be peeping into your screen. You notice if you're talking to the attorneys so they can photograph you as evidence of the attorneys that are plotting with the media. And that is something I've never experienced covering any trial.

ILYA MARRITZ According to prosecutors. He gave perks or favors worth close to $500 million or 1.8 billion shekels to an Israeli telecommunications company in return for positive coverage. We don't know where it's going to end, but where this is headed. Benjamin Netanyahu's reputation may be tarnished, but also the media's reputation could be tarnished.

YAEL FRIEDSON Oh, definitely. Because it's just showing how the coverage was edited and changed for the interests of the publisher. It's like dividing the Israeli society between those who think that someone who's been accused can't be prime minister and those who feel that there was something undemocratic about accusing a prime minister and trying to put him out of his office, not by elections.

ILYA MARRITZ Because prosecutors are making decisions about who to charge and judges are making decisions about how things go – that that is undemocratic.

YAEL FRIEDSON They feel that there was a plot here against Netanyahu in order to take him out of office. They don't believe the charges and that you shouldn't do it anyway against a prime minister who is still in office. Like, if you want to accuse him, do it after he's out of office.

ILYA MARRITZ Is it possible to say whether the Israeli people believe more strongly now in their justice system. Or do more of them tend to think that it is rigged or biased?

YAEL FRIEDSON Listen, in every case, there are sometimes mistakes, especially with these huge cases. There's 330 witnesses. This trial loads of paperwork. It's natural that there would be some mistakes. But in this case, every small mistake is presented as huge and terrible. And you know that it's not a mistake it's part of the plot. The credibility of the attorney is questioned all the time.

ILYA MARRITZ Netanyahu is not only on trial, but he's also running to become prime minister again. What would happen with Benjamin Netanyahu's trial if he is elected prime minister again?

YAEL FRIEDSON It's a big question if he would try to influence or interfere. Some of his party members have already announced that if they will be elected, they would fire the attorney general. That's a threat over democracy. It's scary in a way, I have to say, thinking of what might happen, what actions he might take. Again, the whole legal system.

ILYA MARRITZ It sounds like Israel is way out ahead of the United States in terms of prosecuting former leaders and exploring all of these uncomfortable spaces. What do you think Americans can learn from what's happened in Israel?

YAEL FRIEDSON One of the things that I regret that didn't happen there was at some point Netanyahu's lawyers were negotiating for a plea deal, and it was very controversial in Israel. And people were feeling that in such a case, you can go for a plea deal. You want the court to listen to all of the evidence and then in the end decide if he's guilty or not guilty, but without conspiracies that he agreed for a plea deal only, you know, because he was forced to. But looking backwards, I think that it would be better for Israel if Netanyahu would have got a plea deal, because I feel that it doesn't matter what evidence are shown in court. Whoever supports Bibi just supports him and whoever is against him is against him. And this whole trial just inflames the public atmosphere while it's going on and it could go on for years. So I hope that in America, if they do file against Trump, that he won't fight till the end, but it would be as quick as possible.

ILYA MARRITZ Okay. Yael Friedson is the legal and Jerusalem affairs correspondent for Haaretz. Yael, thank you so much.

YAEL FRIEDSON Thank you. And it's a pleasure.

ILYA MARRITZ Earlier we heard from political scientist James DeLong that some countries choose to prioritize continuity over accountability when it comes to prosecuting their leaders. This past Thursday marked the anniversary of a historic decision to do just that right here in the U.S.A. On September eight, 1974, President Gerald Ford pardoned his predecessor, Richard Nixon, who resigned office one month earlier. Rick Perlstein is a journalist and historian who's chronicled the post 1960s American conservative movement. He says Ford's decision to pardon Nixon still reverberates today.

RICK PERLSTEIN After he resigned for Watergate, as many of his top deputies were facing trial for which they be convicted, including the attorney general, John Mitchell. The statements that the establishment put out there was Nixon's resignation shows the system works. We had brought a president to judgment and it was clunking along towards what was likely to be an indictment. But then Gerald Ford, a month into his presidency, went on TV on a Sunday morning. He probably thought the American people were in the mood for mercy after coming back from church. And he granted Nixon a full, free and absolute pardon for all offenses against the United States, which he Richard Nixon and I'm reading from his document, committed or may have committed or taken in during the period from January 20th, 1969 through August 9th,1974. It was an extremely unpopular move by Gerald Ford. It lowered his approval ratings overnight by 20 points. And for many Americans, it really seemed to suggest that the system didn't work, that presidents were above the law. But time passed. The interpretation of for its actions really kind of made 180 degree reverse among members of the media elite. The political elite.

ILYA MARRITZ You point out in a piece you wrote for Salon in 2014, quote, After Ford died in 2006, Wall Street Journal columnist Peggy Noonan went so far as to say that President Ford, and now I'm quoting her, threw himself on a grenade to protect the country from shame. And he did it because he thought it would help America to move on. And in some sense, it did. No?

RICK PERLSTEIN Well, here we are. Is America healed? I mean, you know, kind of the proof is in the pudding, right? I think that one of the problems with that reasoning is that future bad actors in the White House realized that they could get away with crimes. The very next Republican president and his White House decided that they could break the laws with impunity. That's Iran-Contra.

ILYA MARRITZ Can you just recap for us what we know happened in Iran-Contra and what the illegal activity was?

RICK PERLSTEIN Yeah, sure. Congress passed a law it's called the Boland Amendment, and Ronald Reagan signed it that America could not pass on money to this underground army that was trying to overthrow the Nicaraguan government. And basically, a group of people led by a gentleman named Oliver North, who was a revered and respected figure on the right, now set up an operation in which they basically raised money by arranging to sell missile parts to Iran. Basically, their proxies in Lebanon, where there was a civil war going on, had taken a series of American hostages. And it was often the case that after we sold them the missiles they wanted, they would just keep the hostages anyway or take more hostages.

ILYA MARRITZ I mean, it's sort of like a breathtaking foreign policy Rube Goldberg machine. Do this thing over here to make this thing happen over there. I'm actually astonished they were able to carry it out.

RICK PERLSTEIN And Ronald Reagan actually testified that he didn't have anything to do with the planning of this, he claimed. But he said when he heard it, he thought it was a neat idea, quote unquote. Killing two birds with one stone, getting hostages out, supposedly, and fighting communism. Because, you know, his public policy was that Russia was going to use Nicaragua as a base to invade America. It was quite explicit about that.

ILYA MARRITZ So Reagan said he had nothing to do with this. Was there ever good enough evidence to really link him to Iran-Contra?

RICK PERLSTEIN Well, the real wackiness of this story, you know, people of a certain age will remember this, was that this guy, Oliver North, received immunity to testify. And in one of the most astonishing spectacles, he testified in his Marine dress uniform, made no apologies whatsoever, said he was just a loyal soldier fighting for freedom. And in fact, there was one incident where the actual Justice Department investigators went into his office while he was shredding and asked for documents. And they're like, what are you doing? We're from the Justice Department. And he said something like, Look, you're doing your job and I'm doing mine.

[CLIP]

PROSECUTOR So you shredded some documents because the attorney general's people were coming in over the weekend.

OLIVER NORTH I do not preclude that. Part of what was shredded. I do not preclude that as being a possibility. Not at all. [END CLIP]

RICK PERLSTEIN And the fascinating thing about his explanation was that he didn't think he was admitting to wrongdoing. He thought he was admitting to this great stride for freedom and dignity and liberty, you know, fighting the Soviet empire. That's kind of a cognitive pattern on the right that they're fighting for a transcendent good against a transcendent evil. We see this pattern repeating again and again. Richard Nixon saying if the president does it, it's not illegal. Or, you know, Dick Cheney saying that the vice president's office is a fourth branch of government and the Constitution doesn't quite apply to it in the same way.

ILYA MARRITZ Let's zoom in on the role of Dick Cheney. In the Ford administration, he's the chief of staff. By the time Iran-Contra rolls around, he is a member of Congress. He is part of the committee that's investigating Iran-Contra.

RICK PERLSTEIN The conclusion reached by the majority is that basically the Reagan White House was guilty, guilty, guilty. And the committee that the minority, the Republicans put together said he was innocent, innocent, innocent. Cheney basically moved along this theory that had been kind of long in the gestation that later became described by legal scholars as the unitary executive theory.

ILYA MARRITZ So here's that quote from the report that Dick Cheney helped to author. This is a quote that you sent me. Quote, Chief executives are given the responsibility for acting to respond to crises or emergencies to the extent that the Constitution and laws are read narrowly as Jefferson wished, the chief executive will on occasion feel duty bound to assert monarchical notions of prerogative that will permit him to exceed the law.

RICK PERLSTEIN You will almost expect a trumpet fanfare as the King arrives in his raiment, you know, yeah.

ILYA MARRITZ Monarchical notions of prerogative. Translate that for me.

RICK PERLSTEIN It's a bit of a gaslight because it comes from Jefferson in the most anti monarchical, most democratic of the founders. I mean, it basically means how dare you tell the president that he couldn't defy laws about who the United States could fund when it came to military aid?

ILYA MARRITZ Do you happen to remember where you were or what you were doing when you first read that quote?

RICK PERLSTEIN Yeah, I saw it a couple of years ago and I was like, How the heck did I not know that Dick Cheney was responsible for this utterance? I mean, in a way, it indicts the media for not digging up this astonishing thing. Although people know about this Minority Report and people have written at length about the evolution of Cheney's ideas about the unitary executive. The word monarchical should raise anyone's hackles when it has anything to do with the United States Constitution.

ILYA MARRITZ And we see this idea emerge again in the 2000s when Dick Cheney is the vice president. There's all kinds of questions about the conduct of the CIA around the war on terror.

RICK PERLSTEIN The National Security Agency spying on Americans, the use of what they called enhanced interrogation, which normal people call torture in order to supposedly investigate 9/11. All sorts of very clever lawyering around the idea that Congress did not have an oversight role in any of this.

ILYA MARRITZ We're talking about, at this point, about five decades of sort of building this conservative ideology surrounding the powers of the presidency. What about the Democrats? In this period, what's their view of the president and the law?

RICK PERLSTEIN And the years of Watergate and the Ford administration, the idea was that it was the responsibility of Congress, especially to effect this national housecleaning. You know, both when it came to laws like the first serious campaign finance reform or the laws requiring a judge to approve warrants from the NSA, the FISA courts, or new laws about open meetings in Congress. The Democrats held that to restore kind of the nobility of the constitutional raiment, we had to have reform and beginning kind of in the second half of 1970s was a certain failure of will around that. I think that the Democrats, after losing three presidential elections in a row by these, you know, kind of tough, swaggering guys, the Republicans began kind of losing faith in that reform impulse. This is the basic attitude.

We saw Barack Obama, who after he was elected with quite a striking mandate in 2008 by people who thought in a lot of cases that they were voting to call the Bush administration to account, said, no, we're going to be looking forward, not looking backwards. You know, there were no investigations of, for example, NSA spying by Congress. There was an investigation of torture. And it reached conclusions that were shocking. So it's it's kind of this combined an uneven development where, you know, we do have these reform energies, you know, kind of like now. How the January 6 committee represents, you know, this really kind of strong voice for accountability, whereas a lot of people are questioning how far we can push this again out of this fear that somehow justice can only be achieved at the expense of unity.

ILYA MARRITZ So for this episode of On the Media, we have been looking a lot at other countries, other democracies in particular that have charged their leaders or former leaders with crimes. And the thing that I didn't really appreciate before we started to look at this is just how common this is. South Korea, Italy, Israel, France, South Africa, Brazil. The list goes on. Some of those countries have charged their former leaders more than once. I know this is not your area. America is your thing. But do you think an aversion to holding former presidents to account is in its way, a form of American exceptionalism?

RICK PERLSTEIN I think actually this is very much in the wheelhouse of what's behind all my writing, whether it's my journalism or my history. Is that America often has this almost unique aversion to conflict, precisely because the depths of the division that are just very real in the very conception of the country, which was, of course founded, on this tarnished compromise between the forces of slavery and the forces of freedom are just so deep and people are afraid to open Pandora's box. And the fact that so many other democracies have proven themselves to be kind of more stalwart, more mature shows that maybe, you know, we're not the city on the hill that we like to imagine ourselves as. That we're just far too afraid of our own contradictions, really, to privilege justice over this false and sentimental vision of what we like to call a unity, which might be just a form of cultural repression.

ILYA MARRITZ Rick Perlstein, thank you very much.

RICK PERLSTEIN Thanks Ilya.

ILYA MARRITZ Rick Perlstein is a journalist, historian and author of The Invisible Bridge The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan. Coming up, some media outlets rediscover impartiality – whatever that is. This is On the Media.

[BREAK]

ILYA MARRITZ This is On the Media, I'm Ilya Marritz, filling in this week for Brooke Gladstone. Late last week, reporter John Harwood announced his departure from CNN on Twitter just hours after what turned out to be his last television broadcast for the network in which he commented on President Biden's recent primetime speech in Philadelphia.

[CLIP]

JOHN HARWOOD The core point he made in that political speech about a threat to democracy is true. Now, that's something that's not easy for us as journalists to say. We're brought up to believe there's two different political parties with different points of view, and we don't take sides in honest disagreements between them. But that's not what we're talking about. These are not honest disagreements. The Republican Party right now is led by a dishonest demagogue... [END CLIP]

ILYA MARRITZ In August, CNN also pulled the plug on its Sunday morning media show Reliable Sources and fired the host, Brian Stelter.

[CLIP]

BRIAN STELTER I want CNN to be strong. I believe America needs CNN to be strong. And it will continue to be because all of us are going to help make that happen. For Reliable Sources, for the last time, I'm Brian Stelter. [END CLIP]

ILYA MARRITZ The departure of these two big name journalists raises questions about the direction being set by the new CEO, Chris Licht, who became the boss at CNN in April this year. Licht stepped into the position after former CEO Jeff Zucker was forced out over an undisclosed romantic relationship with a colleague. Licht, the new guy, described it as his mission to, quote, reset CNN. That's the word he used in a meeting with staff in May.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT CEO Chris Licht announced today he has plans to steer CNN away from years of overtly liberal leanings. More towards the middle – groundbreaking, right? [END CLIP]

ILYA MARRITZ In June, Licht banned use of the phrase the big lie in CNN programing. Fox News applauded that polic1y.

[CLIP]

FOX NEWS He wants more objectivity, something CNN has been sorely missing. [END CLIP]

ILYA MARRITZ Jon Allsop writes a daily newsletter for Columbia Journalism Review titled The Media Today. He described a possible best case scenario for what Licht is planning.

JON ALLSOP I think that's part of what Chris Licht is trying to do. If you read the reporting on his intentions is to make the network quieter and more nuanced and give it more room for reporting as opposed to punditry.

ILYA MARRITZ That sounds like something to cheer for.

JON ALLSOP Yeah. And I think in isolation, that is definitely something to cheer for. The problem is there is a very fine line between aspiring to make your network have more hard reporting and less punditry and be a bit more nuanced. And when you're covering politics, retreating to a place where you're treating both sides equally, even though they're not the same in terms of the truthfulness or value of what they're saying, because very simply, there is often this perception that telling hard truths about the behavior of one political party that the other is not doing is partisan. And if it seemed to be partisan, it seemed to be part of that loud punditry thing. Based on the direction of CNN since Licht came in. I think that the concerns that he is trying to take away voices who have spoken difficult and unvarnished truths about the Republican Party, I think that's at least a legitimate concern.

ILYA MARRITZ So that's the reset at CNN. This week, we learned that changes are also afoot at Politico. In the pages of The Washington Post, reporter Sarah Ellison profiled the CEO of Politico's parent company. His name is Matthias Dufner. He's German. And he told Alison, quote, We want to prove that being nonpartisan is actually the more successful positioning. Sounds like he and Chris Licht are both talking the same kind of language about a more centrist approach to the news. Did you see it that way?

JON ALLSOP Yeah, Dufner was actually very explicit, more explicit than Licht has been in saying that he thinks that The New York Times and The Washington Post have ventured too far to the left, and the sources on the right are in thrall to Trump and alternative facts, and that he sees Politico as therefore having this unique market opportunity to position themselves in the center as nonpartisan adjudicators. It's also interesting that story in The Washington Post revealed that he sent an email to executives at his company saying that he would ask them to pray for Donald Trump's reelection in 2020 or something like that. And when the reporter from The Washington Post asked him about it, he said he never sent email, and then she showed him the email and he acknowledged that actually he had sent it, but it was just ironic. So there are some questions about nonpartisanship there, although he denies that, he tells the journalists in his company what to say. The people who think that they could position that news organization as being this completely neutral, nonpartisan thing are actually engaged in something that's much more fraught and difficult than that.

ILYA MARRITZ This kind of discussion about both-sides journalism and even notions of objectivity and impartiality, this is not new. It's been around for decades. We've talked about it on this show for many years. What do you think it says about this moment in time that it's flaring up again in this way?

JON ALLSOP This is obviously something of a hinge moment for US politics. Really the kind of basic rules of the game and just the basic concept of the truth is being challenged by forces of significant political strength in a way that hasn't been seen in a very, very long time. And so naturally, it's going to be a huge question how journalists cover that. And I think you see media critics and just people who consume media getting very frustrated and worried because while there is a lot of good reporting out there that is covering these efforts to erode democracy, we see time and again so much kind of top line political coverage of coverage of elections or coverage of Biden is rooted in these comparatively very trivial routines of optics and who's going to win the next election. And, you know, is this speech good for Biden politically as opposed to sort of hearing the message he's saying in assessing whether it's true or not.

ILYA MARRITZ There are media companies adopting what media critic Jay Rosen calls value-based reporting. There are quite a few newsrooms that are doing democracy beats. The New York Times and The Washington Post both have their versions of this. Public radio stations KUNR and Boston's WGBH. I –this week – joined ProPublica to report on their democracy team.

JON ALLSOP Congrats.

ILYA MARRITZ Thank you. So full disclosure, I think that's a worthwhile thing to do. What do you make of these efforts so far to create democracy itself as a beat?

JON ALLSOP I think those are fantastic efforts. It's great that national news organizations are sending reporters into local areas to report on threats to democracy at that grassroots level. At the same time, I worry about the idea that democracy is a beat. Because the idea of repeats in journalism is that it's discrete areas of interest that specialist reporters at a given news organization will focus on.

ILYA MARRITZ Like the school system, the city hall, whatever–

JON ALLSOP Right! And the problem with treating democracy as a beat is democracy is the precondition underpinning free journalism in America and elsewhere. It's not something that you can sign off as a topic within the broader coverage of politics. It fundamentally restructures everything that politics is. And I worry that you see this kind of great burgeoning reporting on threats to democracy. And then the next page or the next segment, we'll talk about the electoral horse race in a given midterms election. And it's like this analysis that sort of stuck in the 1990s where it seems that the votes will be counted fairly. And the fact that one of the candidates said they don't believe the 2020 election was real. That's sort of treated as a political position. That might be an electoral liability for them rather than a threat. I guess I just don't think you can see democracy in a silo. It's great to have that reporting being expanded, but it's not enough.

ILYA MARRITZ So I want to ask you about the theme of this whole hour of On the Media, which is looking at the idea of prosecuting presidents now that really for the first time the US Justice Department has laid out a lot of the elements of a potential criminal case against former President Trump. Do we have the press corps that we would want to cover a former president being charged with crimes for the first time?

JON ALLSOP I guess what I would say is that while I personally strongly believe that prosecuting a former president, if you follow the facts and the facts lead to that as the course of action that would happen to anyone else is the only game in town here. There is probably a debate that the media should convene about the second order consequences of that. But I do think that a lot of political journalism that I consume is sort of rooted in this view that American government is a collection of norms that shouldn't be breached. There's also, in addition to that respect for norms, this kind of broader American media culture of American exceptionalism, that prosecuting former presidents is not something we do here. That's something they do elsewhere in the world. That's not an American way to do things.

ILYA MARRITZ We spent the past five or six years, we in the journalism community debating and discussing how to cover a norm breaking president and the movement attached to him, that that really threatened a lot of the basis of the way our country works and how to cover it accurately and responsibly. And it seemed to me that horse race journalism and both sides journalism were either on the way out or at least partly discredited. And I guess my question for you is, have we learned nothing?

JON ALLSOP I think there are days where I feel like some lessons have been learned in the news business and then probably many more days where I feel like nothing has been learned. And I would put the coverage that immediately followed the search of Mar a Lago in the "we have learned nothing." bracket. A lot of the coverage seemed to jump to political considerations. Oh, this is a huge risk for Merrick Garland. This is a huge risk for the Justice Department. And there's a ton of commentary, including in mainstream news organizations, that this was great for Trump because the Republican Party had rallied around him and saying this was outrageous and it's super frustrating because you can see the seeds there of, for example, January 6 having been a huge wake up call about the perilous condition of American democracy, that something like that could happen in the U.S. And then you see so much horse race chatter and optics obsessed coverage and punditry, just so much trivial guff that you'd think we'd have learned to leave by the wayside by now. There still seem to be institutional incentive barriers to fully learning the lessons, and I think some recent trends in the news business would suggest maybe actually that what we're seeing in some areas is a retrenchment back towards more old school journalistic practices that the Trump era showed not to work. Rather than taking bold explorative steps in the opposite direction of working out how we can cover this moment more urgently and more honestly.

ILYA MARRITZ Jon Allsop, thank you very much.

JON ALLSOP Thank you for having me.

ILYA MARRITZ Jon Allsop writes a newsletter for Columbia Journalism Review titled The Media Today.

That's it for this week's show. On the Media is produced by Micah Loewinger, Eloise Blondiau, Molly Schwartz, Rebecca Clark-Callender, Candice Wong and Suzanne Gaber. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineers this week were Andrew Nerviano and Adriene Lily. Katya Rodgers is our executive producer. On the media is a production of WNYC Studios. Brooke Gladstone will be back next week. I'm Ilya Marritz.