Man of the Left

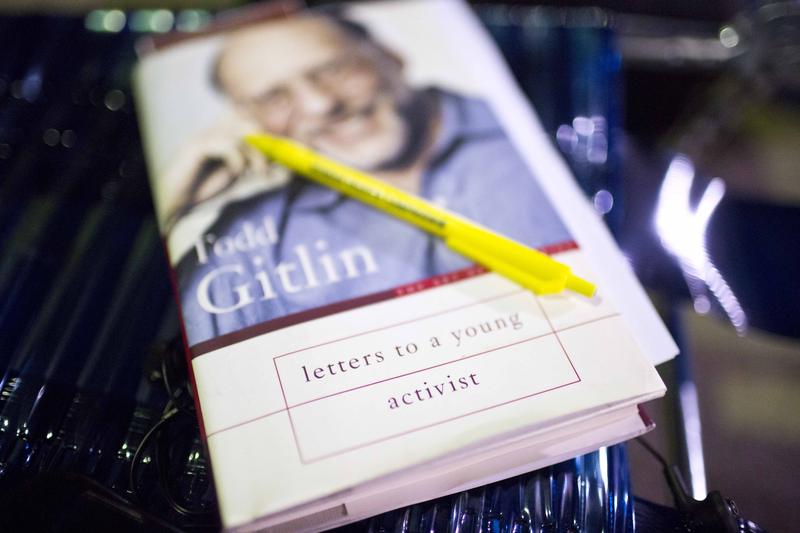

( Brynn Anderson / AP Photo )

Brooke Gladstone: I'm Brooke Gladstone. This is On the Media's Midweek Podcast. Todd Gitlin writer, media analyst, sociologist, and lifelong activist died on February 5th. In his youth, he helped organize the first national demonstration against the Vietnam war held in Washington in 1965. He organized rallies against South African apartheid and four civil rights in America. Later as an educator and author and media critic of the right and the left.

He worked as an observer and shaper of thoughts about our media narratives until the end of his life. Gitlin was also a mentor to many and a huge influence on many more, especially those who came to the nascent field of media criticism after him. Among them, New York University journalism professor and media critic, Jay Rosen, writer of the oft-quoted PressThink blog and a regular here on our show.

Jay Rosen: I met him in the early '90s in and around Tikkun magazine, which was a Jewish magazine of the left, then headquartered in New York. Then he began to help me establish myself as a media critic and started inviting me to things and giving me things to do well before I had earned them. Maybe on some hunch that I could develop into something someday. That's how I knew him.

Brooke: There are an abundance of media critics in the world. I asked Jay what he thought made Gitlin unique.

Jay: Several things. First of all, he started out as an activist, not as a media observer or critic. He was president of students for a democratic society. The most important organization of the new left in the early '60s. He had a lot of experience in activism and organizing people. In fact, he kept that up throughout his life. I don't think anyone would even try to count the number of open letters that he circulated and got people to add their names to.

He was an activist throughout his entire life, and he was very self consciously and openly excuse the expression, man of the left. He never stopped being of the left. Yet he developed critiques of the media that many people could benefit from. There were hundreds, maybe even thousands of journalists who learned the benefits of giving Todd a call when they were doing stories about the media. You might be one of them.

Brooke: Yes.

Jay: All of those things combined, I think to make him a unique voice.

Brooke: He was a man of the left as you say. In his very influential book from 1987 called The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage, he wrote the quote, "He and other student organizers were living in a bubble talking to ourselves like a narcissist admiring himself in a TV screen." Do you think that self-consciousness influenced his perspective on activism and his perspective on the media?

Jay: Well, I think what influenced both was the fact that the left did not triumph. His hopes for the new left did not come true. Not that he thought his activism was wasted or pointless, but I think he was always trying to answer the question, why aren't we getting through, why aren't we making the kind of change we want to see? He never stopped asking those questions even as the answers became more complicated. That was one reason he had such tension with others on the left is he was constantly warning his fellow liberals or left-wingers that they could be self-defeating. That was a major theme of his work as well.

Brooke: He saw the political landscape and the media change dramatically in his lifetime. Long after his time as a "freelance agitator," as he called it, he became more critical of the party he'd embraced as you suggest. Why do you think it has something to do with falling into the same rhetorical traps? Both progressives and conservatives or maybe not. What do you think?

Jay: Well, I think one of the things that was really unusual about Todd was he never stopped being a man on the left, but he was critical of his own people as a world, but he never gravitated to the right either, nor did he take comfort in just being more radical than thou. So in a lot of ways, he was a pragmatic critic of American society and he never lost that even though he had to live through what for him, incredibly disappointing events, enraging events. That's one reason that he had such an influence on me is that he had a temperament and a balance to his views that was really inspiring because he always had a view from somewhere.

Brooke: You wrote the view from nowhere. In other words, he didn't pretend to be one of those passionless priests of journalism on the hill.

Jay: Right. Nor did he pretend to be a social scientist who just dealt with the data and tried to divine social patterns from the evidence of their quantitative studies, which was a point of view in sociology that he critiqued as well. He was the political, intellectual, public intellectual who never overly politicized his subject, but also never pretended not to have politics hit the forefront of his views.

Brooke: That's what makes his pragmatism so interesting. He once wrote, "The only people available to change the world are the people now living in it with all the beliefs they bring along, however, retrograde those beliefs may appear to those of us who see ourselves as enlightened."

Jay: He said to recognize diversity, more than diversity is needed. The commons is needed. To affirm the rights of minorities, majorities must be formed. This was the point of view that he brought to the left. As in his mind, it began to splinter into identity politics, which is a contestable term, of course.

Brooke: What did he mean by that? I'm not sure I understand it.

Jay: It means that you can't just be a collection of minorities and form a powerful force. You can't have a movement that is all about recognizing the rights of the groups within that movement. You need a common world, you need a common set of demands.

Brooke: That's the pragmatism, right?

Jay: Yes. Also, Todd was very aware of something about American history, which is that it's the big institutions that ultimately have to make the changes. Stereotypically, Congress has to pass the Civil Rights Act, but it never happens because of Congress. It happens because of movements, social movements that force those actions, and he never escaped into valorizing one or the other. I think he held both in tension in his mind.

That's another reason for his pragmatism is he believed in the power of institutions. He also thought a lot of them were corrupt. He believed in the power of movements, but he also knew that movements could go awry. This is one of the reasons he influenced me is that I wanted to avoid some of the excesses that he took on his shoulders to critique.

Brooke: This is one of the reasons why I wanted to call you. We find you a wonderfully bracing critic, partly because you have suggestions for how to fix things. Not that anyone is inevitably going to pay attention, but they're really good suggestions. You posted a thread about Gitlin's ideas, the ones that particularly influenced you. We've had you on the show talking about some of those very ideas. I think they offer a great summary of some of his best insights about the media. First, you mentioned a 1990 essay for dissent, blips, bites, and savvy talk.

Jay: Well, I developed this critique of the savvy style in journalism, which I think is the actual ideology of the American press. Meaning the press isn't really left. It's not right. It believes in its own savvy and it identifies with the professionals in politics who also try to have a savvy outlook on what moves voters, what wins campaigns.

Brooke: Savvy, is that kind of a word that in your context means a kind of cynicism?

Jay: In the way that I try to develop it, savvy means you admire what's effective and what wins even if it shades the truth, even if it's slightly corrupt, even if it makes things worse. It's the people who know how to maneuver the system and win that journalists admire. I'm very suspicious of the admiration that political journalists have for the savvy minds in politics. I don't trust that instinct.

That critique emerged out of my reading of this article in 1990 in descent, in which he has this amazing phrase where he describes the objects of the savvy style as inviting people to become connoisseurs of their own bamboozlement. You can see if you read a lot of media criticism, if you'll read a lot of political journalism, you can see how inviting people to become the connoisseurs of their own bamboozlement is very much what the savvy style is about. I trace the rise of that style of criticism in my own work to my encounter with this essay in dissent by Todd Gitlin in 1990.

Brooke: Then in his 1983 book, Inside Prime Time, which was based on interviews with 200 makers of commercial TV, you were introduced to the concept of audience lore.

Jay: This is a really important moment for me in learning how to be a media critic. Inside Prime Time was the result of 200 interviews with people who make commercial television, producers primarily. The people who run shows, the people who make the decisions about what gets on prime time. As he talked to them, they would, of course, base their decision-making and what they thought the audience would go for or want to see.

The more he talked to them, the more he realized that very often they were commanding a story about the audience, what he called audience lore, which wasn't necessarily grounded in data. Rather, it was a sign of status when you could be the one to interpret the audience, be the one within the company who knew what the audience wanted. It was as much a mark of rank within the corporation, as it was of any certain knowledge about the audience and its tendencies.

I still use this insight all the time every day on Twitter when, for example, people explain to me that this is happening to CNN because of ratings. I even have a pet name for rating zoo idiot, which is something that is said to me like 25 times a day, as if I never heard of ratings or knew nothing about it. Of course, everybody knows ratings are important and that they're a religion and that they arrive in people's desks every day and everybody knows what they say.

Even when the ratings are like hard numbers that nobody can ignore, the interpretation of those ratings still requires human beings. Very often that is done by people who have the most status or the most power in the organization not necessarily because they know the most about the audience. I drew from Inside Prime Time, a much more subtle understanding of decision-making in commercial environments. That book remains one of my favorites that he wrote.

Brooke: You also said that he had an effect on your language as a writer.

Jay: Yes. The effect that Todd had was similar to the effect that Neil postman had. I did my dissertation with Neil Postman and studied with him for many years at NYU. He was like a God to me as he was to many other people. Both Neil and Todd had this ability to write in a very learned way without devolving into jargon. They were learned writers, but not academic writers.

They could do academic argument if they needed to and they had read and absorbed the great works of the 20th century in social theory and social criticism but they never allowed that to become a specialized language that only other experts or others in the discipline could master. I think the biggest achievement of Todd as a writer throughout his long career is that he never oversimplified, but he also didn't overcomplicate. He believed, I think, in the importance of a common language, just as he believed in the importance of having a common agenda and having the commons itself as a place where people could meet despite their differences.

As an academic myself who didn't want to write just for quarterly journal articles [unintelligible 00:15:18] and other professors, but who wanted a public voice, I watched everything that he did as a pro stylist, just as I watched everything Neil did as a book writer and as a public commentator and tried to work out my own version of that so that I could write at the intersection of academics interested in the media, journalists who have to improve their practices, and members of the public who are dissatisfied with the journalism they're getting. In order to do that, you can't speak the language of any one of those three groups, you have to find one that works for all three. In trying to do that, learning how to do that, I took my cues from Neil and from Todd and they were both masters of it.

Brooke: I was going to ask you what of Gitlin's commentaries you think feels the most relevant to our current precarious position politics. You mentioned that he co-wrote or wrote many open letters and got people across the political spectrum to sign them and that your last missive from him was this open letter in defensive democracy, calling for people to "protect the very practice of free and fair elections in which winners and losers respect the peaceful transfer of power." That was in late October, his final act, I guess.

Jay: In a way, yes, or one of them. In that note, you'll notice that he's collaborating there with William Kristol, a Neoconservative that Todd would've been very much in disagreement with for many years in American politics.

Brooke: Not only that, John McWhorter, the Columbia University professor of linguistics has run up against many progressives and Charlie Sykes and other anti-Trump Republican who seems to sign on all of these things, but also Sean Wilentz, Michael Tomasky, [unintelligible 00:17:23], Dahlia Lithwick, really a very impressive list and mostly from the left, but definitely not entirely, it was also published in William Kristol's, The Bulwark, which is definitely not a progressive publication.

Jay: Keep in mind that Todd was not only a man of the left, but he started out as part of the radical left. He wanted radical change. The SDS, Students for Democratic Society saw itself as radical in the sense of going to the root of the nation's problems. For him to organize this open letter, people crossing the ideological divides is no small matter. This is another thing that I really admired about Todd.

He taught you if you watched his moves carefully that it's not enough just to have politics, you have to be good at politics. You have to be smart about it. You have to make the right choices. His record over the years was really good at that even though he got in lots of arguments and lots of people got very mad at him as well. Just the importance of showing good judgment of not overreacting, but not underreacting either, those are the kinds of things that impressed me.

Brooke: Did you read Michelle Goldberg's column in the New York times?

Jay: I did.

Brooke: I thought it was really moving. She describes his looking back on encountering Irving Howe, an old man on the left, when he was a young radical one, and how he pretty much dismissed the elder Mr. Howe's irrelevant. I think it proved a cautionary tale for him in some ways that he didn't want to retreat into a kind of senescence. Michelle quotes the end of the book, The Sixties. It ends with a quote from Rabbi Tarfon who lived around the first century AD, "It was not granted you to complete the task and yet you may not give it up." Michelle Goldberg concludes, Gitlin never did.

Jay: That's an amazing quote. In some ways, he became the Irving Howe for the next generation of people on the left. As his colleague, Mitchell Cohen, said, also a dissent writer, "It could be said that Todd Gitlin believed in the left that learns, and I thought that was a really good way of capturing what was really great about Todd. That's another reason he was so influential to me, because as professors, we have to be the ones who are really good at continually learning not just teaching but learning, and he was a model for that in many ways.

Brooke: Jay, thank you very much.

Jay: My pleasure. Thank you, Brooke.

Brooke: Jay Rosen is an associate professor at NYU's Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute and the founder of pressthink.org. Thanks for listening to this week's podcast. On the big show available Friday evening, we'll be trying to answer a whole bunch of questions about this Joe Rogan story. Join us for what we hope is an illuminating hour. Also if you need another fix of OTM in the week, sign up for our newsletter written by the incomparable Xandra Ellin. Just go to onthemedia.org.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.