The Lasting Impact of the Library of Alexandria

( Pier Paolo Cito / Associated Press )

Brooke Gladstone: This is the On the Media midweek podcast. I'm Brooke Gladstone. In the first half of the last school year, PEN America has recorded almost 900 different books pulled from library shelves across the country.

News clip: The American Library Association are tracking more book bans than ever, and many of them are aimed at books with the LGBTQ+ themes.

News clip: As teachers in Florida had to cover up their bookshelves for fear of getting sanctioned or fired.

Brooke Gladstone: Mothers For Liberty, a Florida-based conservative political group has been campaigning fervently for book bans in US public schools with some success.

News clip: Not since the Daughters of the Confederacy has there been a conservative women's organization as influential as Moms for Liberty. They're taking the lead in getting books banned all over the country, are directly allied with governor, a noun, a verb, and fight the woke Ron DeSantis, and they're on a winning streak.

Brooke Gladstone: As long as libraries have existed, people have tried to police what goes in them, but for some, the ideal library is not one that excludes authors, but rather a place that comprises all of them. For centuries, scientists and inventors, philosophers, and programmers have been inspired to envision or even build a better library, a perfect library, one that stocks every book ever written, the kind of library that may have actually once existed. Late last year, On the Media producer Molly Schwartz went to her local library to meet some of the people trying to build a universal repository of human knowledge to learn what kind of progress they've made and what keeps the dream alive.

Molly Schwartz: It's a gorgeous fall Saturday in Brooklyn. Mild chill in the air, colorful leaves, general good vibes, and I'm on my way to a birthday party at the Brooklyn Public Library at 9:30 in the morning.

News clip: Welcome everyone to Wiki Data Day. Today is Wiki Data Day. It's the 10th anniversary of Wikidata. So Wikidata is the data science side of Wikipedia.

Molly Schwartz: You know Wikipedia, the free online encyclopedia with millions of articles and hundreds of languages all written by volunteers. Jim Henderson is one of them, and today he's wearing two hats. Literally.

Jim Henderson: This is the data hat, something I ordered when I was on the board of directors of the local club.

Molly Schwartz: The data hat says I heart Q60. Q60 is Wikidata for New York City. On top of it, he's wearing a beanie that says Wikimania Cape Town.

Jim Henderson: When we had our next to last Wikimania Worldwide convention.

James Forrester: So we have this kind of mission statement for the Wikimedia movement.

Molly Schwartz: James Forster is a software engineer at the Wikimedia Foundation.

James Forrester: Imagine a world in which all people have access to the sum of human knowledge.

Molly Schwartz: Providing everyone on the planet access to the sum of human knowledge. That's the prime objective of Wikipedia, as stated by co-founder Jimmy Wales.

James Forster: It's a mission statement. You're not meant to achieve them, you're meant to move towards them. Definitely, we've moved a huge amount towards them in the last 20 years. Pushed the ball along the road a little bit.

Molly Schwartz: As the day goes on, I learn about Wikidata properties and qualifiers. I also get in a little bit of trouble because On the Media's Wikipedia page isn't up to date.

James Forrester: Added Suzanne Gaber, publish the changes, and it's done.

Molly Schwartz: Thank you.

James Forrester: It needs some more links.

Molly Schwartz: I spoke with someone who thought a lot about universal libraries and how they work.

Richard Knipel: I grew up with the 1940s Britannica in the 1960s World Book, and I wanted to contribute to the sum of knowledge.

Molly Schwartz: Richard Knipel is the president of Wikimedia in New York City but in the world of Wikipedia. He's known by his username Pharos.

Richard Knipel: Named after the Pharos of Alexandria, the lighthouse of Alexandria. It's in homage sort of to the Library of Alexandria.

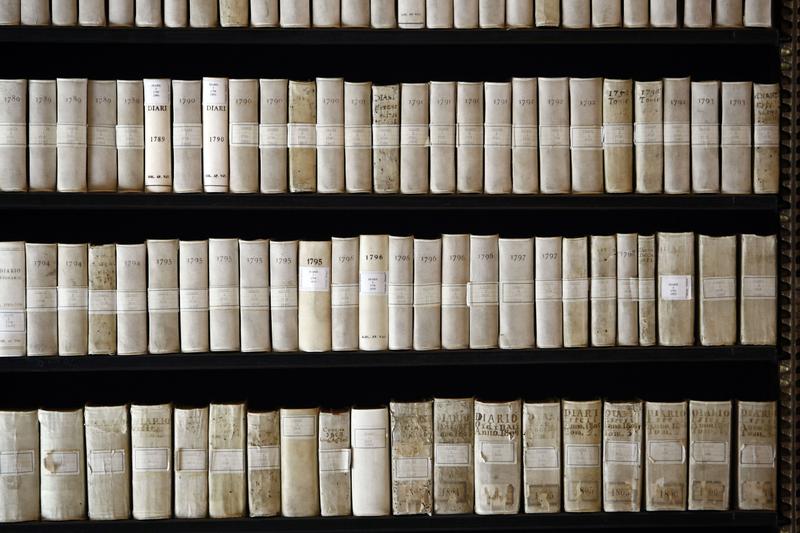

Molly Schwartz: Perhaps the closest thing there ever was to a universal library, a bastion of all the world's knowledge for all who seek it.

Richard Knipel: We actually had our international Wikimedia conference, we had Wikimania was in Alexandria a few years ago, and people do feel a strong cultural resonance with Library Alexandria and other universalizing attempts at knowledge.

Alex Wright: For some reason, the Library of Alexandria has captured people's imagination. It was certainly the largest library of its era.

Molly Schwartz: Alex Wright is the author of the book, Glut: Mastering Information Through The Ages. He says the Library of Alexandria was built in Egypt in the third century, BCE, likely by decree of the Pharaoh Ptolemy I.

Alex Wright: And he tried to attract as many notable scholars as he could to come and contribute to the collective enterprise of building not just a library, but a university and its center of learning.

Molly Schwartz: Ptolemy's mandate for the Library of Alexandria was as ambitious as it was simple, collect everything. Every papyrus scroll, every book, every manuscript, by force if necessary.

Alex Wright: When ships would come to Alexandria, officials would basically seize the books on the ship and add them to the library.

Molly Schwartz: They lifted books from private citizens, stole them from docked boats, and allegedly took books via subterfuge from Athens. But despite the Ptolemy's best efforts, Alexandria could never really compete with Athens. Athens was this organic center of culture and learning, whereas in Alexandria, all the scholars were entirely beholden to their employer, the Pharaoh. So as the Ptolemy empire crumbled, so did the library.

Alex Wright: There's this deeply intertwined relationship between libraries and state or governmental power, and you find that the great libraries of the world have not coincidentally emerged alongside powerful empires or civilization.

Molly Schwartz: What happened to the library is actually unclear. Some say Julius Caesar burned it down. Others say a conquering Muslim commander burned the books, and others say that the library never succumbed to a fire at all. But rather to years of neglect and changing empires.

Alex Wright: We don't know for sure exactly what happened. We do know for sure that the library no longer exists and that the 500,000-odd volumes of material there have for the most part been lost to posterity, and yet there's something apparently energizing about that ideal that has inspired a lot of people over the years to try to work towards some kind of universal repository of recorded information.

Molly Schwartz: Versions of universal libraries pepper science and speculative fiction from Jorge Luis Borges's magical Library of Babel.

News clip: The universe, which others call the library, is composed of an indefinite, perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries.

Molly Schwartz: To Isaac Asimov's Imperial Library in the Foundation Series.

News clip: I was just in the Imperial Library on Trantor. In the stacks. The ceiling was wooden, there were all these marble busts.

Molly Schwartz: To Douglas Adams's Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.

News clip: The Hitchhiker's Guide has already supplanted the great Encyclopedia Galactica as the standard repository of all knowledge and wisdom.

Molly Schwartz: To the TV show, Doctor Who.

News clip: The library, every book, ever written, whole continents of Jeffrey Archer, Bridget Jones, Monty Python's Big Red Book.

Molly Schwartz: There's even a universal library in the world of the occult, according to theosophists.

News clip: The Akashic records is a place within a different dimension. It's a higher dimensional energy that is like the library of the universe. It holds all the records of the universe. And anybody can tap into this energy, into this knowledge, and access it for themselves.

Molly Schwartz: Around the invention of Gutenberg's printing press, the Vatican Library was also founded. According to Pope Nicholas V, the goal was ensuring "for the common convenience of the learned, we may have a library of all books in both Latin and Greek that is worthy of the dignity of the Pope and the apostolic sea." Then in the late 19th century.

Alex Wright: Suddenly printing of books became a industrialized mechanized affair.

Molly Schwartz: Alex Wright.

Alex Wright: You started to see this explosion of popular literature, magazines, what they sometimes called penny dreadfuls, these cheap little precursors to tabloids.

Molly Schwartz: It was during this explosion of books that people started paying attention to how to organize and retrieve them using universal classification systems.

Alex Wright: That was when Melvil Dewey invented his decimal classification. There was another guy named Charles Cutter, working the Boston Athenæum, who developed a different classification system that's now used in a lot of academic libraries. In India, there was a librarian named Ranganathan who developed a really highly sophisticated method that he called faceted classification.

Molly Schwartz: Then in the 1930s, with huge leaps in technological progress following World War I, came another burst. This is when the visionary H.G. Wells published a series of short stories. In them, he explained a concept called the world brain.

Speaker 17: There is no practical obstacle whatever now to the creation of an efficient index to all human knowledge, ideas, and achievements. To the creation that is of a complete planetary memory for all mankind.

Molly Schwartz: Around the same time, Paul Otlet, a librarian in Belgium, envisioned the World Book.

News clip: Here, the workspace is no longer cluttered with any books. In their place, a screen and a telephone within reach. Over there, in an immense edifice, are all the books and information. Cinema, phonographs, radio, television: these instruments will in fact become the new book.

Molly Schwartz: Vannevar Bush, who worked for President Truman as what was effectively the nation's first science advisor, wrote about a memory supplement that he called the Memex.

News clip: The analytical machine which will supplement a man's thinking methods, which will think for him, will have as great an effect as the invention of the machine way back took the load off of men by giving them mechanical power instead of the power of their muscles.

Molly Schwartz: Basically, these imagined groundbreaking gizmos are proto-computers and proto-search engines. They were all invented, and more and better. With all of this came another round of optimism, starting in the '90s and picking up speed in the aughts and 2010s, that the dream of a universal library could be realized via the internet.

Brewster Kahle: I'm a librarian and the idea of using technology is perfect for us.

Molly Schwartz: That's Brewster Kahle again, the founder of the Internet Archive who we heard from earlier in the show.

Brewster Kahle: I think we can one-up the Greeks and achieve something. Yes, we could actually achieve the great vision of everything ever published. Everything that was ever meant for distribution available to anybody in the world that's ever wanted to have access to it.

Molly Schwartz: There was a host of these projects all at the same time because people all had the same vision, put books online. There was also the Universal Library Project, which was later largely supplanted by HathiTrust, which is this massive cache of digital content that's available to a group of research libraries. Then there are projects ranging from the World Digital Library to the Digital Public Library of America, and all kinds of smaller offshoots.

News clip: Walk into the Bexar County Digital Library in San Antonio, Texas, and you'll see plenty of screens, but zero books. This doesn't look like a library.

News clip: No.

News clip: That's the point.

News clip: That's the point.

Molly Schwartz: The one that probably had the grandest vision, the most top-down, the most completist, was the Google Books Project. Google transported truckloads of books to their massive scanning centers across America. They got their technology good enough that they were scanning about 1,000 pages an hour. Since 2004, they've digitized over 20 million books, and they have plans to literally digitize every book in the world. Google Books was a huge deal, the company's first moonshot, the first salvo in a revolution.

News clip: What is being discussed tonight, is not your ordinary kind of revolution, like cars and jets. It is a super revolution like writing and printing and computers.

Molly Schwartz: Google Books was sued by the Author's Guild for violating copyright. Ultimately, Google won, but only because they only show snippets of most books, a far cry from the initial vision of universal access.

Gyula Lakatos: Unfortunately, I'm still using a mobile internet plan.

Molly Schwartz: Gyula Lakatos is a software engineering consultant. He lives in a house on a hill in a small town in Hungary, on the banks of the Danube, too far from Budapest to get high-speed internet. That's a problem because he's working on a very large project housed in two servers stashed behind him.

Gyula Lakatos: One of them is running 20 hard drives, the other one is 10.

Molly Schwartz: Lakatos is using those servers to save just a little bit of today's digital flood for posterity, inspired by deep admiration for the ancient empires of Greece and Rome, and fearful that modern civilization will suffer the same fate as those lost knowledge centers.

Gyula Lakatos: As far as I know, only like around 1% of books and documents survive from classical antiquity.

Molly Schwartz: Which made him wonder what's going to be left from life today.

Gyula Lakatos: I created an application suite. It's not just one, it's seven applications. You can deploy these applications to crawl the web.

Molly Schwartz: He spent about $6,000 on equipment that ran his applications for two years, amassing over 90 million documents onto the servers in his house. His application suite is open source and available on GitHub. You'll never guess what it's called.

Gyula Lakatos: It's called Library of Alexandria.

Molly Schwartz: At this point, he's collecting around two million documents a week. They include everything from interesting complex doctoral dissertations to the kind of ephemera of restaurant menus to a weird collection of Russian passports. It's a mishmash of the valuable and long-forgotten, all hoovered up and stored in the hills of Hungary. Lakatos wants to open up his treasure trove to the public. For now, it all just lives on his servers because he's afraid about copyright laws, and navigating copyright laws for 90 million documents, that's a job for more than just one person.

Gyula Lakatos: I don't really want to host it to be honest. I'm a lazy person. I just want to search in that library. That would be a lot of fun.

Molly Schwartz: I came across Lakatos's project on the subreddit called data hoarder. It's a forum for people with a kind of unusual hobby, trying to preserve things they find on the internet. They hoard this data in their living rooms and corners of the web and sometimes on places where a lot of the web is hosted, Amazon Web Services, or AWS. It's all to try to preserve a first draft of history for the future.

Gyula Lakatos: Humanity in general can lose a lot of knowledge out of nowhere for no reason. Imagine that, for example, a fire is starting in one of the AWS warehouses where a lot of things are hosted and people just lose their data. The whole data hoarder subreddit is very concerned about this. I just wanted to notify people with this name a little bit, or warn them a little bit more.

Molly Schwartz: I appreciate these data hoarders. I got my degree in library science because when I stood in the rare books room at my university, I felt a sense of awe. Like I'm part of a story that began long before I was born and will go on long after I'm gone, I hope. In the glut of information, more gets lost than saved. That's not always a bad thing. One of the first things an archivist learns is that the best way to save things is to know what to throw away.

Have you ever noticed that the material on which knowledge is stored has gotten more ephemeral with time, from carved stone to parchment to paper, to tape and floppy disks, to drives for outdated devices, to everything stored in a cloud, prey to all kinds of terrestrial and cosmic events? The fact is preserving all the world's knowledge is like building a dam against the unyielding torrents of time. It's impossible, but if we don't keep trying, how will anyone know we were ever here? For On the Media, I'm Molly Schwartz.

Brooke Gladstone: Thanks for listening to this week's midweek podcast. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.