Great White Lies

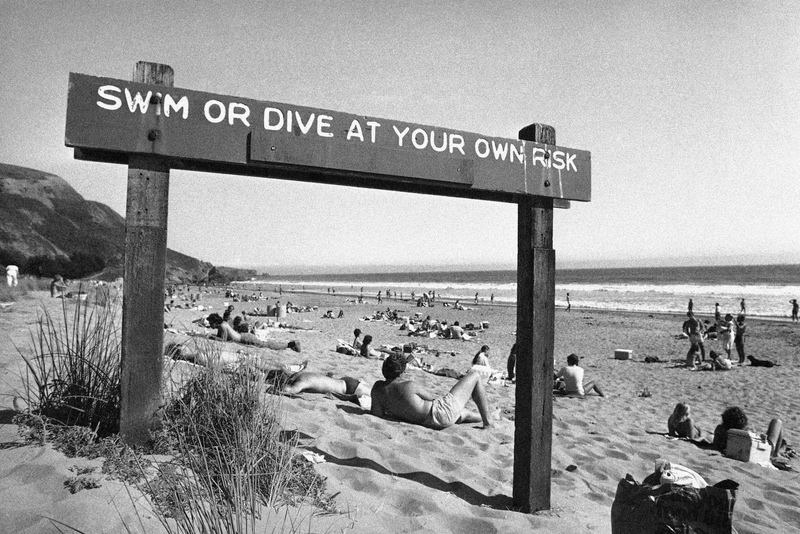

( Paul Sakuma / AP Photo )

Micah: Hey, it's OTM correspondent Micah Loewinger. I'll be filling in for Brooke on Friday's episode. First, for this week's pod extra, we decided to take a cue from Discovery Channel because it's shark week and you know what that means.

Speaker 1: The mako shark, the ocean's king of speed.

Speaker 2: Take it off.

Speaker 1: A vicious hunter.

Micah: This year's program boast flashy titles like Stranger Sharks, Air Jaws, Great White Serial Killer, Rise of the Monster Hammerheads, featuring sharks writhing through murky water, jaws clenched on dead fish bate, snapping at divers.

Speaker 3: There is a creature alive today who has survived millions of years of evolution.

Micah: Of course, sharks first splashed into Hollywood and widespread infamy with the 1975 blockbuster Jaws.

Speaker 3: It lives to kill, a mindless eating machine. It will attack and devour anything.

Micah: It's the type of horror film that sticks with you, especially when you go for a little swim at the beach, and you float in there, looking out over the waves, you start to think to yourself, "What's out there, what's underneath me?" That video was captured just last weekend on the New York Coast. According to experts, there's been a slight rise in shark sightings and incidents over the last three decades.

Speaker 4: Experts are warning that sharks will be out and about in force along both the east and west coast over the July 4th weekend.

Micah: Even as these predators shut down beaches and send local news crews into a frenzy, many marine biologists have waged a counter PR campaign for sharks, arguing that popular media have far overstated their danger. Chris Pepin-Neff is a senior lecturer at the University of Sydney and author of the book Flaws: Shark Bites and Emotional Public Policymaking. He says that a half a century before Jaws, sharks first received their brutal reputation from a handful of researchers, including Horace Mazette, a writer and big game hunter.

Chris: Horace Mazette, from New York, writes these books about sharks in the Great Barrier Reef. He is convinced that sharks get shark rabies and sharks get a taste for human flesh, and so he starts writing letters to an Australian, a shark researcher named Victor Coppleson, who is writing to people to contemplate shark behavior. Mazette, he tells Victor Coppleson, "You have to convince people that sharks attack people." Victor Coppleson writes the authoritative journal article of its day in the Australian Medical Journal, stating that the evidence that sharks attack is complete and that changes the paradigm, and shark attack becomes much more prominent in the literature.

Micah: Is the idea that prior to this discourse, people weren't afraid of sharks, like there just wasn't a kind of a popular imagination of the menacing shark at the beach?

Chris: That's exactly right because beach-going was seen very differently. In a lot of communities, there were propriety laws in the 1800s that kept people in onesies. What you end up with is a total change in the culture post-1911, 1912. The laws start changing, become more progressive, more liberal, people start swimming.

Micah: You said there's a couple of other human factors that changed how we came to perceive sharks. One of them had to do with shark bites and what happened to people after they were bitten.

Chris: Sharks' teeth are really bacteria-laden and create real problems for humans when we get bitten. Most people who were bitten by sharks in the '20s and '30s, really received very minor bites but died as a result of it, from sepsis or from some other bacteria-based infection.

Micah: The assumption was man dies from shark bite, a ginormous hulk of flesh was removed from their body, when it may have been an actual infection from a smaller bite that took their life.

Chris: That's correct, that's predominantly what happened.

Micah: Speaking of human behavior, there were also different environmental factors that led to an increase of interactions with sharks as well.

Chris: As communities got developed, let's use New Jersey, 1916 as the example, they set up resorts, and they didn't have the sewage capability to manage it without flushing the sewage out into the open ocean. That's what happened in lots of areas, and so you had construction waste, you had sewage that was flowing, and that would attract bull sharks, other sharks, other bait fish that sharks follow to come into shore. We're going into the water, the sewage is going into the water, and the sharks are coming into the shore, and the combination of those three things is a fundamental shift in the dynamic between humans and sharks.

Micah: You mentioned, 1916, in New Jersey, there was actually something remembered as the New Jersey Massacre on the Jersey Shore. This was like an early media frenzy that did a lot to kick-start the public perception of sharks. Four people died, one person was injured. Newspapers reported there was a man-eating shark. I saw a picture of it. That is like the biggest, baddest thing, I'm sure, many people had seen. It was said that it was a single malicious shark, I'm paraphrasing here, that was on a killing frenzy.

Chris: There's one researcher who notes and I think correctly, that it's kind of the Titanic of shark attack cases because previously, you've got this belief that sharks don't bite North of the Caribbean, that jaws aren't strong enough. Now, you've got four fatalities. You've got a shark in a river inlet going up the Jersey Shore. President Woodrow Wilson is paying attention to the concerns of high-dollar donors who are based on the Jersey Shore, who are living at this resort. Woodrow Wilson has shark attacks put on the war cabinet agenda and deploys the coast guard to go assist in finding the shark.

Micah: Were they successful in tracking the shark down?

Chris: There was a shark that was caught and killed and there were remains that were found in the shark, so it was believed that this was the shark. Basically, after this occurred, the shark bite stopped so everyone thought the problem is solved.

Micah: It's fascinating to me that the area that I'm speaking to you from the New York, New Jersey area is so crucial to the origin of our modern perceptions around sharks because there have been shark sightings on New York beaches this summer. According to the Australian Shark Incident Database, shark bites have actually been on the rise over the past four decades. What do you think are some explanations for this?

Chris: Population is on the rise. The population of people who use the ocean is on the rise, the amount of time we spend in the ocean is on the rise, the number of things we do on the ocean is on the rise. We go to more areas to go in the water, we pick more remote areas, surfers are in search of the barren beach, the places that would be most opportunistic to sharks, and you've got to think about sharks as these opportunistic apex predators, we're a big thing where we don't belong, and that makes us a target.

Micah: Just to drill down on the language a little bit, do all of the bites that have been reported, do those count as attacks, how should we make sense of those two words?

Chris: Usually, shark bites count as shark attacks, which is unfair because I did a study with Bob Hueter who used to run the Mote Marine Lab. What we found is that in a government report, about 38% of reported shark attacks had no injury. The narrative is much more complicated, whether it's a surf ski that gets bitten or a surfboard that gets bitten or someone knocked off a boogie board or something. All of this is usually getting counted as a shark attack. What we find is that that's not actually an accurate reflection of what's going on in the water.

Micah: A recent article in Hellgate, which is a local New York online publication, noted that there is a distinct hysteria associated with a shark attack that isn't representative of the likelihood of the threat. For instance, it's very arresting to see shark attack in a headline or on tv, see a deserted beach, but the odds of being attacked by a shark are like 1 in 3.7 million, but the chances of dying in a car crash, writes Hell Gate, are around 1 in 101.

Chris: There's a reason why they say it, "If it bleeds, it leads." Shark bites sell. Shark attack is a visceral concept. We have an idea of it, we know what sharks look like, we know what a shark bite is, and we know that a shark attack would be a terrible thing to have happen to someone.

Micah: That idea that we have in our head really feels like it comes from one particular moment in media history. Do you want to just say it?

Chris: Jaws.

Micah: Yes. Which is an awesome movie. I don't want to dunk on Jaws as a film, but you think that it's had an adverse effect on how we think about sharks.

Chris: Peter Benchley, who wrote Jaws, said it had an adverse effect on sharks. He said, "I never should have written it."

Micah: It was pure fiction, right? He wasn't a shark expert.

Chris: He wasn't a shark expert, but he had read, this is another New York connection, he had read about a large shark that was caught off the coast of Montauk. He got the idea in his head. "What if the shark that was caught off Montauk terrorized the community off that beach?" That was what precipitated the writing of the novel, Jaws.

Micah: What's your experience when you watched this 1975 film directed by Steven Spielberg?

Chris: I love Jaws. Who doesn't like a murder mystery who done it starring a killer fish? That's got all the elements you want.

Micah: [chuckles] what do you think about the Sharknado series?

Chris: I think Sharknado actually has done a ton of good because--

Micah: Really?

Chris: Yes, because sharks flying through tornadoes is not a normal meteorological event. The fact that people can distinguish between normal shark behavior, like shark bites is mistaken identity, right? You look like a seal. I think the movie characterization of sharks as characters has helped to distinguish between actual real shark behavior and movie monsters. The problem with Jaws was that people thought that it was a movie monster that was a real shark and that that could really happen.

Micah: You alluded to Woodrow Wilson calling out the New Jersey shark massacre and drawing attention to it and helping shape the public perception around sharks. There seems to be this funny part of American presidential history where American politicians have looked to sharks to prove their own masculinity. Tell me a little bit about how JFK looked to sharks.

Chris: JFK is on this boat, PT109 in World War II. There are stories about how PT109 crashes and JFK then has to swim through shark-infested waters to survive. That story builds a legacy and an iconic picture of JFK as having the character and the strength of purpose because sharks are depicted as so menacing. If JFK has swung through dolphin-infested waters, that would not be a story.

Micah: It would be a different story, that's for sure.

Chris: It'd be a Disney story.

Micah: JFK wasn't the only president to use the shark as a foil for their own masculinity.

Chris: Exactly. FDR uses that as a foil in 1938 in a fight with a 235-pound shark that he spent 90 minutes reeling in and brings the board the ship and takes a picture of the shark hanging by its business on the boat. That's a picture of strength for FDR that's an important narrative about masculinity that is being conveyed.

Micah: Nixon also flirted with the imagery of sharks. Donald Trump in 2018 gave a speech in which he mentioned sharks.

Donald Trump: I'm not a big fan of sharks. I don't know how many votes am I going to lose. I have people calling me up, "Sir, We have a fund to save the shark. It's called Save The Shark." I say, "No, thank you. I have other things I can contribute to."

Chris: Anyone who helps a shark is no friend of mine or the only good shark is a dead shark, kind of thing.

Micah: You've been on the front lines of a movement to change how people in the media and other researchers talk about interactions between humans and sharks. I've certainly seen some coverage of this reexamination of the term shark attack. There was a piece last year in the New York Times, Stephen Colbert quoted you, the global shark attack file changed its name to the global shark accident file. The Australian shark attack file also changed its name to the Australian shark incident file, but not everyone has been so receptive to this reexamination. For instance, Tucker Carlson wasn't a big fan.

Tucker Carlson: Officials are referring to shark attacks as we're quoting now, "Negative interactions," like when a great white choose off your leg, it's a negative interaction. One university of Sydney researcher said, "The move is appropriate because most shark attacks are more like small bites than actual attacks." How to assess this? Well, Dave Portnoy is most famous for starting these sports site.

Micah: According to him, you're like a social justice warrior who's one incident in a larger culture war of the left trying to change every little bit about how we speak.

Chris: I'd say to Tucker, I did a study and found that 66% of people thought shark attack was overhyped. The public doesn't want it. It's not an accurate of reflection of what's going on. We should change the language to something closer to shark encounters when there's no injury and shark bite when there is an injury. It is not my position that shark attacks should be retired completely. It is just that unless the intent of the shark, which is awfully hard to know, you shouldn't be calling it a shark attack.

Micah: Can you give me some examples of counterproductive public policy responses that are rooted in ignorance of sharks?

Chris: The New Jersey shark Fisher was started in the '60s because of the 1916 shark bites. You ended up with having a fisheries policy that was directed by shark bite policy.

Micah: The idea was if you see a shark, kill it?

Chris: Yes. Any good shark is a good shark. That becomes a public policy of the United States. After Jaws, sharks are seen as waste fish, and they increase shark tournaments where you go and have big game hunting. Again, building on the machismo thing of going and conquering the ocean, catching kill as many sharks as you can, as often as you can.

Micah: There are real stakes here because sharks are crucial to the health of our oceans, and their population has decreased by about 70% since the 1970s, largely from overfishing and human destruction of their environment. If we don't reassess our relationship to sharks and how we talk and write about them, what do you fear will happen?

Chris: If you start killing apex predators in marine ecosystems, really bad things happen. Any marine scientist will tell you that eliminating the top of the food chain creates more problems, not less problems. There was an incident where they were overfishing for white sharks off Durban, South Africa, and dusky sharks moved in. Well, dusky sharks have a bite radius that is harder than a white shark. When they introduced people into those scenarios and they ended up being dusky shark bites on humans, they were more severe because you were introduced, what's called a Mesopredator, which is the one below the apex predator, into that situation. When humans metal, good things do not happen.

Micah: Chris, thank you very much.

Chris: Thanks so much for having me.

Micah: Chris Pepin-Neff is a senior lecturer in Public Policy at the University of Sydney and author of the book Flaws: Shark Bites and Emotional Public Policymaking.

[music]

Micah: That's it for this week's pod extra. Don't let Brooke's absence deter you. I think we got a nice show plan this week. See you on Friday.

[music]

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.