On the Inside Looking Out

( AP Photo/Rick Bowmer, Pool, File )

Brooke Gladstone: Now, it's really spring. With the change of the seasons come rituals that remind us of what matters in each of our lives. That is when we come to you, except in summer, we don't usually come then, to ask for your support because we matter to you. At least, we hope we do. If you've never supported us with a donation anyway, would you now? It doesn't matter how much. If you have, would you please do it again? If you're a sustaining member, would you consider giving a little more? Our show is ongoing, 20 years so far, and so is the need. Not just for us, I'm thinking also for you.

Our world never ceases to be interesting and challenging. Pandemics, injustice, leaders to be held accountable, entire systems falling in on themselves, riddled with rot, that need to change. An ever-shifting reality, lots of them in fact, that cry out to be explored. That's what we do every week, and we need you, really need you to keep going. Want to be part of this weird project called On the Media? Just text OTM to 70101. That's OTM to 70101, or go to onthemedia.org and click on "Donate." Thank you.

[music]

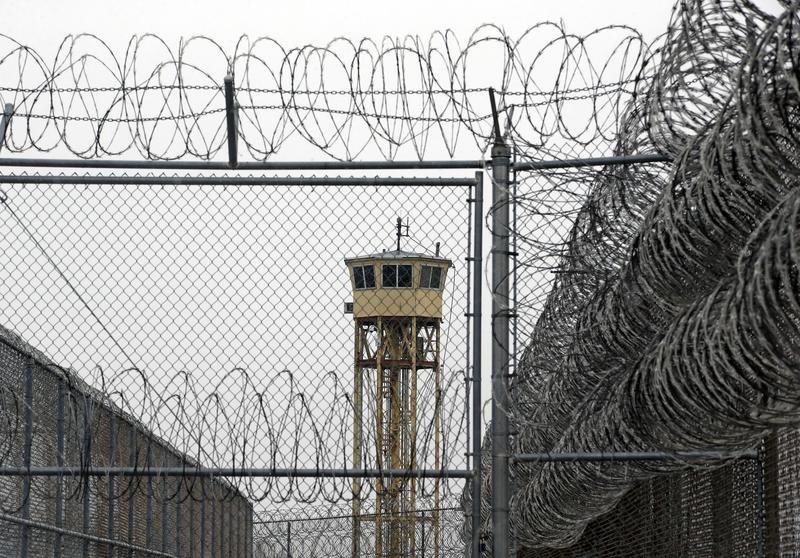

Brooke: This past year, most of us were awash in a news cycle driven by the pandemic. Daily, we grappled with infection data, vaccine updates, social restrictions and public officials trying to balance fatigue, facts, and safety. There are some in the country cut off from the deluge, offered instead merely a trickle. Obviously, the American prison system wasn't built with the pandemic in mind, with inadequate spacing for quarantine, cleaning supplies, and access to healthcare. The pandemic has focused a brighter light on decades-old issues surrounding incarceration, including access to information about news and policies that could be matters of life and death.

John J. Lennon has been especially concerned. He's written about prison life under COVID in The New York Times Magazine. He's a contributing writer for The Marshall Project, contributing editor at Esquire, and an advisor to the Prison Journalism Project. He's also serving an aggregate sentence of 28 years to life at Sullivan Correctional Facility in New York. That accounts for the quality of the line.

John J. Lennon: I am in the belly of the cell block, and I'm calling you on one of four phones.

Brooke: You've been at the Sullivan Correctional Facility in New York for 19 years, right?

John: That's correct. For a couple of years around Rikers Island, fighting the case, and now convicted and sent up for 28 years to life.

Brooke: Have you challenged the verdict?

John: No, I'm guilty. I killed the man. I was in drug dealer. I was in my early 20s. I take full responsibility for what I did.

Brooke: When did you start writing?

John: I learned how to write in a creative writing workshop in Attica. In about 2010, this professor came in from Hamilton College and he volunteered to teach a creative writing class. I just stumbled into the class and just took to it.

Brooke: There's a scene in an article you wrote in February about getting the Sunday edition of The New York Times. You subscribed to the actual print edition. You say you loved the texture and the smell but it's expensive, and so there's a literal line in your cell block to read it after you're through?

John: Well, I'm one of the fortunate ones that actually get The New York Times. New York Times is pricey when you subscribe to it. A lot of folks can't afford that. We don't get online as most people do so I pass it on when I'm done. There's just a line of guys. "Let me get it after you. Let me get it after you," that kind of thing. Some guys get a little disgruntled when I pass it to somebody before. It goes by seniority, who's been here. I try to let them work that out amongst themselves, but there are several people that want to read it, yes.

Brooke: Could you describe what news consumption is like for people in prison?

John: There is a kiosk and there's an online Associated Press they have. Mainly, depending on what prison you're in, some prisons have TVs in their cells. Currently, Sullivan Correctional Facility where I'm at does not have TVs in their cell so we mostly get our news from NPR or periodicals, subscribe to periodicals. This is a big radio jail. If we're going to get news, we're going to get it from NPR.

Brooke: [chuckles] NPR is popular?

John: It is. Brooke, I'm a big fan of yours. [chuckles] I was telling your producers, I was like, "I love Brooke Gladstone." I enjoy the show.

Brooke: Can you talk to me a little bit about misinformation? One of your cellmates thought Hank Aaron died from taking the coronavirus vaccine. How do ideas like that get around?

John: It's the same way it gets around on the outside. There's a lot of misinformation on the internet. We call home, and depending on who we're calling, it's where we're getting the information from. It's pretty much like the same misinformation that's out there. I'm dealing with it right now. They approved Johnson & Johnson and there's been some unfortunate news about blood clotting. Everyone's saying, "See, they had us all lined up. They're going to give us the Johnson & Johnson and we're all going to die."

You have to sift through that, and it's difficult for individuals. It's difficult for me as a journalist, I just try to report the story. I try not to convince people of what they should or shouldn't do.

Brooke: Now, public radio, obviously, is not always right. It hasn't always been right about the pandemic but there's a serious effort to try to be right. I just wonder whether people consuming different news sources within the prison have debates over, say, the efficacy of vaccines. Is anybody's mind ever changed or is it exactly how it is on the outside, and it's very difficult to get anybody to change their mind?

John: It's a good question. The administrators could perhaps do a better job with informing folks. I think people on the outside want to know what's going to happen with their travel restrictions, what's going to happen with their local gym. They want to know what their life's going to look like. I think the same goes with folks in prison. They want to know are they going to be able to hug their family on a visit. They want to know are they going to be able to attend their family reunion program, which is a conjugal visit where wives can come up. If I don't get the vaccine, am I going to be prevented from seeing my family?

That's really not being conveyed. To be fair to corrections also, the judge just ruled that we're all getting vaccines and they're still trying to sort that out. Hopefully, there'll be a campaign where they can give us some information so we could see what our life would look like and make informed decisions as to whether to take or not take the vaccine.

Brooke: You had mentioned that The Final Call, the newspaper of Louis Farrakhan's Nation of Islam, has been very skeptical of vaccines. That view's gotten around.

John: Yes, some of the fellows do subscribe to that.

Brooke: Do you remember what the headlines were?

John: Yes. "We don't want your vaccine." "Big Pharma. Big money. Big fears." Understandably, the African American community have good reason to be skeptical about government studies. There's good reason for that.

Brooke: How about your family on the outside? Are they skeptical?

John: Everyone's talking about the vaccine. My mom lives down in Florida. Look, I'm not out there. My presence is not felt. I'd be pretty persuasive if I was with my mom, but I'm not, I'm over a prison phone. People are in a hurry here. She doesn't want to take it. My mom, she's like, "I don't want it. They should give it to you." She's saying, "I think they shot water in that Joe Biden's arm." Then my aunt comes to visit her. It's a cast to character, when I'm calling home. My aunt's a fan of Trump. I'm trying to navigate this over prison phones, and I'm like, "Stop it. Don't listen to Mary Ann." I'm saying, "Just take it." It's difficult.

Brooke: You mentioned how expensive The New York Times is. What is the cost of information, good or bad? Family and friends can serve us links to the outside world, but even talking to them isn't free. In your article, you highlighted a prison communications firm. This is a private firm called Securus Technologies.

John: Look, you have to understand. It's a controversial issue. It's a private contractor, it comes and makes deals with the state. It has deals with plenty of states. They have phones and now they have this new technology. They own the company JPay where they have these tablets, and there's a tablet program now. Basically, on those tablets we can send emails, 30 second videos from family. I haven't seen my mother, she has Parkinson's. I really enjoy those videos. I can cut and paste on an email, I was never able to cut and paste, and I could use email. I'm a journalist, this helps me. I'm a fan of the program-

Brooke: But there's no internet?

John: No internet, correct. They charge you for each email. They've come under scrutiny for this, but when you are using Walkman and a typewriter for my whole 20 years I've been in prison, close to it, you're grateful when you get some technology. I thumb tapped much of this piece of The New York Times Magazine using JPay.

Brooke: Securus Technologies provides JPay, this access to the tablets. It also owns phone contracts for a lot of prisons and county jails, and charges can go as high as $14 for a 15 minute call, but downloading your mom's 30 second video only costs a buck, right?

John: Yes. The thing about it is, those contracts, certain states and certain counties, they allow that. The public sector is culpable here. New York State prisoners won a lawsuit, so they can't really charge us that much but other counties and states, they do. There's probably just as much culpability on the elected officials of those counties and their states.

Brooke: Securus, when it comes to phone service, is really cashing in. I thought it was surprising, though, that you argued that these tablets are actually a reason, at least for now, to keep for-profit companies invested in the prison system.

John: I did argue that. I was looking at both sides. I appreciate the tablets. Of course, I don't appreciate other incarcerated people being charged $14 for a 15 minute phone call. I think it's absurd, and I think it needs to stop. In terms of the tablets here in New York, I think the program has some issues, but in totality it is an added benefit and it enriches the quality of our lives.

Brooke: Tom Gores, the business man whose private equity firm own Securus, was called upon by an advocacy group called Worth Rises to divest from the company. Worth Rises opposes any private companies profiting from incarceration, and it put an ad in the New York Times saying, "If Black Lives Matter, what are you doing about Detroit Pistons owner Tom Gores?" The ad called him a prison profiteer. Has Mr. Gores ever responded to the controversy?

John: He acknowledged that it's a controversial thing, and it probably should be taken up by nonprofits. Guess what? Nonprofits don't have the infrastructure to do it. If big, bad Tom Gores is not coming in here offering us technology, I'm still typing on my typewriter. I'm still listening to my Walkman. I'm in the '80s over here. The government's not doing it.

Brooke: You're saying there's no operating alternative to JPay right now?

John: No, there's not. Look, I wish I could read the New Yorker online, the Atlantic online. You know how I forget that stuff? People take snapshots of great articles. When I have to do research for an article, people take snapshots of those articles, and then send them as pictures on JPay so I could get the message in real time. Alternatively, they can make a copy and put it in the mail if I want to read a great article online. Also, I just subscribe to the print edition, but not everything online, as you know, appears in print.

Brooke: You're lucky because you have family and friends who can support you in this way and materially?

John: Yes, I'm self sufficient. I don't depend on my family, but they have been very nice over the years. I earn my own income with journalism, I'm very grateful for that. I think it's a nuanced situation. You really can't have a bank account. This law in New York says you cannot profit from your crime in writing about your crime. The exception to the Son of Sam Law is earned income though. I earn my income through journalism. Anytime that I extensively write about my crime, I've donated that money to nonprofits, usually doing criminal justice work.

Brooke: Beyond JPay, is there another best step, maybe something advocates or lawmakers should be considering when figuring out the access to information that inmates can and should have?

John: Who's it on? Is it on the public sector or the private sector to offer that? I wish that, instead of AP that I could download online, Atlantic articles or online New Yorker articles. I think that's on the provider, but that's also on some of the magazines that sort of get past, let's be honest, they've rough reputation that Securus has. Who wants to make a deal with them when they're sort of scrutinized like that? hen guess what? We don't have that information to your point. It's a really, really thorny issue.

Brooke: What are the stakes here? I began with the anecdote in your piece in the Times about people lining up for the Times, but does there seem to really be a hunger? Would it help them in prison? Is it something that is really worth paying attention to, among so many other things?

John: Absolutely, absolutely. I am where I am today because of access to the articles and the magazines that I mentioned. I learned how to write in that creative writing workshop in Attica, but I would spill over these feature magazine articles and reverse engineer them and really, really wonder how these writers do what they do. That's because my mom subscribed to these magazines. I was privileged to have a mother that had. Unfortunately, a lot of folks don't have that extra money. To answer your question, of course it's important, but these are private corporations too, these media companies. I think the question is, how important is it to them to get us the information?

They have a lot of gorgeous writing online that I wish my peers can read. Sometimes I don't want to give up my New Yorker Magazine because I have these gorgeous sentences underlined. I don't want to give up my Esquire, magazine. I don't want to pass that on. We started this interview, we went down a road of questioning the ethics of Securus, about a lot of money being made in media in America, and maybe it's a question we need to put on these companies. Some of them are colleagues of national editors and chiefs at these places.

I actually thought about writing an open letter to Jeffrey Goldberg and David Remnick and saying, "Hey, make a deal with Securus. Let us read The New Yorker, let us read the Atlantic, because it really helps me as a human being to read such gorgeous writing, an important reporting.

Brooke: In a piece earlier this month, you wrote about skepticism of the vaccine being pretty widespread. Is there a source of information that is trusted enough by the skeptics to open them up to taking a vaccine?

John: They came in a couple of days ago after the court ordered that all New York incarcerated people in jails and prisons get the vaccine. They said, "Yes or no, you're getting it or not? Let's go, yes or no?" There are officers coming around, "Yes or no?" That was inappropriate. I think we need to be a little nuanced about how we approach this. There's a lot of influential prisoners, and if administrators don't lean into relationships with influential prisoners, like, for example, during this crisis, and they don't look to work with them, say, "Hey, we have this problem here. We are looking to get as many people vaccinated as we can."

We don't want to tell you to press the population, just to inform the population within candid conversations about some of the things I mentioned earlier, "This is what's going to happen." We won't be able to use this, or go on this visit, or attend that." There needs to be more communication, Brooke, and you need to tap into your resources. We're not liabilities, some of us are assets. Many of us are assets.

Brooke: John, thank you very much.

John: Thank you so much.

[music]

Brooke: Thanks for checking out our midweek podcast. You can hear the big show on Friday. We usually posted around dinner time, and it's going to be good.

[music]

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.