To Name, or Not to Name

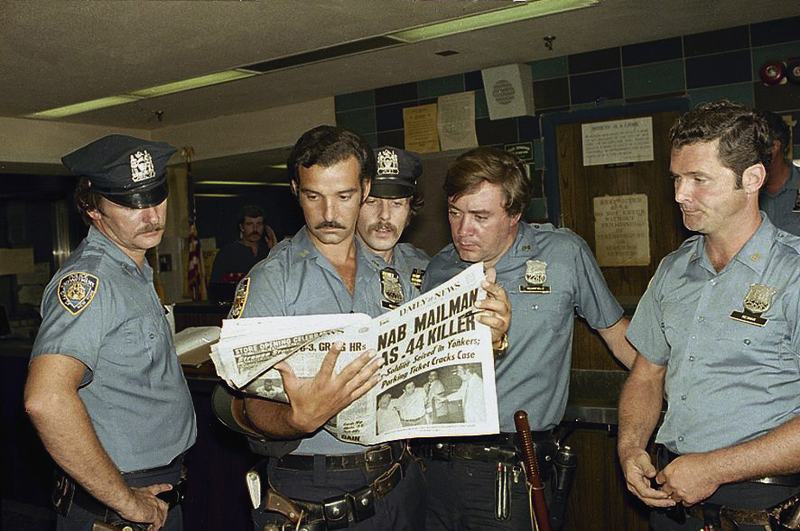

( Suzanne Vlamis / AP Images )

Bob Garfield: This is an On The Media podcast extra, I'm Bob Garfield. Journalism at its core has always been a matter of who what, when, where, why. Perhaps most particularly with crime reporting where journalists and reader alike are impelled following the what happened to discover who the victim is and who done it. It is an immutable principle of news coverage or is it? Across Europe and now sometimes here, news organizations are often withholding the who. The so-called right to be forgotten established seven years ago in the Spanish court case to prevent online searches from permanently unearthing an individual's worst moment, has in some cases been expanded to immediately protect criminals and alleged criminals from media shaming.

In other cases, it has been flipped to the society's right to never offer criminals notoriety in the first place. Romayne Smith Fullerton is a journalism professor at the University of Western Ontario. She and Duquesne University journalism professor Maggie Jones Patterson are authors of Murder in Our Midst: Comparing Crime Coverage Ethics in An Age of Globalized News. Hey, welcome to OTM.

Romayne: Thank you.

Maggie: Thank you.

Bob: As I understand it, you guys blundered upon this topic on a trip with students. Maggie, can you tell me about that?

Maggie: Sure. This was in 2009 and I was taking some students on a tour of newsrooms in Europe. When we were in the Netherlands we visited ANP their national news service, which would be the counterpart to the Associated Press in this country. A story that had just happened that was a big one the editor there talked to us about, was an attempt to assassinate the Royal Family on the Queen's birthday, a national holiday in the Netherlands. I knew this story because it was of international fame. I had heard it before we left the United States.

She was telling us about that coverage and said, "The man who had done this crime killed 7 people, injured 10. He never reached the Royal Family but he crashed into a monument and died the next day but told the police that his intention was to assassinate the royal family." Then she told me that they put his name in a separate file, but did not put it in the story. They identified him only as Karst.T. I was just astounded, and I said, "You what? Why would you do that?"

She was surprised by the question and said, "That's just the way we do things here. We generally name criminals although our clients, or news organizations who use our service can decide to and that's we do include it for the historic record and to give them the option to use it."

Bob: You said to yourself, " Ah, there is some scholarship to be done here." In due course, you and Romayne started scholaring in 10 countries mostly in Europe, but also Canada and the US of A. Romayne I gather it was a quite a variety pack of journalistic approaches that you discovered?

Romayne: Yes, we did find a variety of approaches, but basically we also ended up finding enough similarities that we created 3 different groupings of those 10 countries. 3 different media models that we aligned because of their largely similar approaches and underlying attitudes about naming or not naming.

Bob: What are they?

Romayne: The first grouping would be what we call the watchdog countries. Those are the ones that we're most familiar with here England and Ireland and then Canada and the United States. The second grouping we call the protectors. That's where by and large the practice is one of protecting accused and convicted persons and those under that media model were the Netherlands, Germany, and Sweden. Then in the third model, the ambivalence, is Spain, Italy, and Portugal.

Bob: Now wanting to know who done it or who allegedly done it is such a human thing. Putting aside what constitutes the public's right to know, there are whole genres of literature and TV and film not to mention centuries of newspapering built on that achingly compelling question. In these various buckets of practice, what rationales did you encounter for including or withholding full names?

Maggie: Well, we started with the Netherlands and Sweden. The most frequent answer given and the answer given with the most emphasis was that they felt that they should protect the families who were innocent and particularly children. Actually, the editor in the Netherlands that I talked to first, who launched this project, asked me what I taught students to do when crime reporting. I said, get first name, last name, middle, initial, address, a picture, or a mugshot. She put her hand over her mouth and gasped and said, "Why would you do that to someone?" They feel that they can tell about the person without identifying them. One ombudsman in the Netherlands, news ombudsman said he had never received any feedback from readers who ask for more information. They only protested that they got too much.

Bob: That's interesting because in the United States the imperative to get more not less information about the alleged culprit, includes giving us facts that almost don't matter but become embedded in the public consciousness. Lee Harvey Oswald, for example, John Wilkes Booth. We know Assassin's middle names because in a vacuum of actual information at the time that's what news organizations can give us. These European countries take entirely the opposite approach.

Maggie: Yes, although the information is there if they want it, their records are public, anybody could go to the courthouse and get the name. There are websites that do reveal the names and there are tabloids that reveal the names. It's what's standard practices, but not uniform practice.

Bob: In most cases, this isn't necessarily the law I gather, but it is codified in journalistic canon no?

Romayne: In the Netherlands and in Sweden, the practices are codified in ethics codes but those aren't laws. People follow them because they believe that's the right thing to do not because it's required that they do that. They have freedom of the press in the same sense of the word that we have it here in North America, but journalists routinely choose to protect names and identities because they believe that's the ethical thing to do. Because they believe that stories about crime can be told without naming a person and sometimes implicitly by shaming them. Naming implies a punishment.

Bob: Particularly when someone has been convicted of a crime, why protect them from the shame attached to it? What is the public's benefit in insulating criminals from the opprobrium about their acts?

Maggie: I think that's particularly hard for Americans to understand because we have very punitive attitudes toward criminals. The attitude that we encountered in the protector countries, Sweden, the Netherlands, and Germany was that one of us had committed a crime but he's still one of us. Their system is geared to rehabilitation and to being able to reintegrate this person when they're released from prison if their sentence-- Their sentences are much lighter than ours and many criminals are not imprisoned. But that he can resume a productive life and become a good citizen again.

Bob: I often know what the hell I'm doing when I do this show, but I have to say I completely misread the thrust of your work. Because I assumed that you guys are going to be talking about a fourth bucket altogether and that is the right of a society not to reveal the names of culprits less they turn the criminals into heroes or antiheroes. Particularly, for example, in New Zealand when the incel mass murderer became a symbol of the movement such that it is, thanks largely to the media and the prime minister said, no, don't do that.

New Zealand Prime Minister: He sought many things from his act of terror but one was notoriety and that is why you will never hear me mention his name.

Romayne: There's been a similar case although not quite as high profile here in Canada. In 2018 a man in his late twenties rented a van and then he drove it onto a sidewalk in downtown Toronto and he killed 10 people, and he severely injured 16 more. He was charged with murder and a variety of other charges. There was just a verdict announced in that case last week and the judge took the unprecedented step of not naming the accused in her reasons for finding him guilty.

She referred to him as John Doe for exactly the same reasons as the Prime Minister of New Zealand. That was because in the case of this man in Toronto, Ontario, he said he was setting out to make himself famous. The judge said she hoped that media outlets would observe her request not to name him, not to give him the very thing that he said he wanted. Broadcaster: In part, the judge refrained from naming the killer in her decision. It's a move that's being applauded by victim's advocates. We should note that CBC News will continue to use his name though sparingly, it is our job to provide facts and information for our audiences.

Bob: This murderer, the judge called him John Doe, I'll just call him AM because his name is widely available in public.

Maggie: Is widely circulated.

Bob: Yes, exactly. This sentence was just a week ago. I'm curious now you're from Canada, Romayne. I wonder if there's been any public reaction to the judge's decision to John Doe this monster instead of calling him by his name?

Romayne: I would say that the reaction has been mixed. One of our best known calling this is a woman named Rosie DiManno and she writes for the Toronto Star, it's the largest metropolitan daily in the country.

Rosie DiManno's lead after the judge's request to anonymize AM, was she led with his name written three times AM, AM, AM. You need to know who he is and we need to say it because he's the person guilty of murder, etcetera, etcetera. In the same newspaper that day, there was a column written by a victim's advocacy group thanking the judge and saying that this was a new and brave idea. Hoping that other media outlets would see the value in not playing to the sensational aspect of this and denying the murderer the infamy that he requests. Then there are all kinds of gradations in between.

In fact, I would say that the conversation has continued along those veins. I would also just point out that the reason why some journalists and columnist, and some people generally are willing to shield AM's name is not at all related to the reasons why they do so in the Netherlands. Here, they're shielding the name if they choose to do that out of deference to the victims, out of trying to re-focus coverage on those who lost their lives and those who continue to suffer. Which is a very different reason from the protectionist policies in places like the Netherlands, and Sweden, and in Germany.

Bob: This isn't just a theoretical formulation, when the crime happened in New Zealand the perpetrator in his so called manifesto gave a shout out to AM, as have others throughout the incelosphere, in those quarters he's not just a hero, he's a guiding light.

Romayne: Yes, he serves as an inspiration and that's precisely the reason why the judge and other advocates are not using perpetrators names in these particular instances in these kinds of crimes. It's not that there's any invocation of a law against it, it's a request to do so for what a lot of people would consider the right reasons.

Bob: I want to talk about the watchdog bucket the United States and England so far, seem to find this whole anonymity thing hard to swallow. What did American journalists tell you?

Maggie: American journalists were very articulate about why they do what they do. They felt that it was the public's right to know, it was a public record, and that they had no right to withhold that information. One Irish reporter was incensed and thought it was very unethical that the Dutch took information and treated it in this paternalistic way, by not giving it out to the public. They also felt that they would not trust government, they would worry about the police getting out of hand if they didn't say who was arrested and why they were arrested.

The head of the Dutch Journalist Union said to us, "Well, you don't trust your government and you have good reason not to." He was talking to me the American part of this team, "But we do trust our government." They don't have the same watchdog attitude. They don't feel that they are required to keep an eye on institutions and with quite the same vigilance and perhaps skepticism and even animosity that's frequently part of the English speaking world.

Bob: I want to ask you about the relationship with government, because the rationale for getting all of the details about alleged perpetrators and victims is all rooted in the public's right to know. Which is to say the government is compelled to tell us things that perhaps the government may wish to keep close to the vest, but they have to and it has become kind of muscle memory for us to grab whatever detail we can. Is it possible that the very distrust of government that is so core to our civil liberties is the wrong approach for a society when it comes to crime?

Maggie: That's not a judgement that we felt was warranted. Clearly for the protector countries, especially, because we have the highest contrast with them, this is right for their culture, this is right for their history. In the watchdog countries, even though we share so much common culture, this is a big difference among these countries. That's why we really felt it was important to write this book because very few journalists, and we talked to almost 200 knew that what they did was not what everybody did.

It's just an amazing ignorance that the technology has leapt way ahead of our knowledge of what these boundaries contain, and we feel should be preserved. That a country ought to be able to determine what its culture needs and doesn't need.

Bob: It wouldn't be too hard to imagine how a government under the pretext of protecting criminals from undue public exposure would twist that, abuse that, into secret arrests. Which is as illiberal an idea as you can imagine. Could that somehow become a problem in the most liberal democracies in Western Europe?

Maggie: It is a problem in Southern Europe. For example, in Portugal a case that we looked at there where the former Prime Minister was arrested, and arrest means different things in different countries, by the way. We have arrest in charge wedded to each other, in other countries, people can be arrested but not charged for some time, and it can be up to 10 months.

In Portugal, where this Prime Minister was imprisoned with no charge made, and no public release of what even the investigation was about, or if it had to do with the time that he had served as prime minister. As it turned out it did, but it was an interesting example of how police there leak information to select media, but don't necessarily make a public announcement because they're not required to by law.

Bob: Well, that's a slippery slope if ever there was one, how worried should we be?

Maggie: Well, the protection of innocence is a principle in every one of the 10 countries that we went to, but what people thought that meant was very different in different countries. Even though the protector countries put the protection of family first, they put the protection of innocence right after that. That was also an issue in southern Europe, in Spain, and Portugal, and Italy. Their laws enforce a protection of innocence by not releasing information about people who are arrested. Yes, it struck Romayne me as a very slippery slope and dangerous precedent in countries that had dictatorships not that long ago, but that's the way their legal system operates.

Bob: Now, here in the watchdog, United States, as a society we have spent a lot of time particularly in the last year of introspection. Looking into our justice system and the systemic racism that informs many dimensions of the society, but especially law enforcement and jurisprudence. In some ways, the press maybe deemed to be accessories during and after the fact to the injustices that are perpetrated by the system. Do you expect that these programs by The Boston Globe and the Cleveland Plain Dealer may find themselves becoming common practice throughout the American media?

Maggie: One of the theses of the book was that crime serves as a lens to understand deeper generally held cultural attitudes to aspects of justice. Crime practices that each country and each media model use are reflections of deeper attitudes held by the public and citizens individually. As citizens and as communities and countries come to revise those attitudes. It makes sense to me that crime coverage practices and journalism generally will change, because those values are changing. That makes sense to me.

Bob: Romayne, Maggie, thank you so much.

Maggie: Thank you, Bob.

Romayne: Thank you for having us.

Bob: Romayne Smith Fullerton is journalism professor at the University of Western Ontario. Maggie Jones Patterson is journalism professor at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. Their book is titled Murder in Our Midst: Comparing Crime Coverage Ethics in an Age of Globalized News. This has been an OTM podcast extra. Check back this week for the big show when we look at the most personal battlefront in the war against genuine climate action, your home. Meantime, if you aren't a subscriber to the OTM newsletter, you are missing an entire highly profound dimension of understanding of our world plus very funny. Go to onthemedia.org/newsletter and subscribe now. I'm Bob Garfield.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.