'We've Sort of Become Friends': The Original Tapes from David Foster Wallace's '96 Book Tour

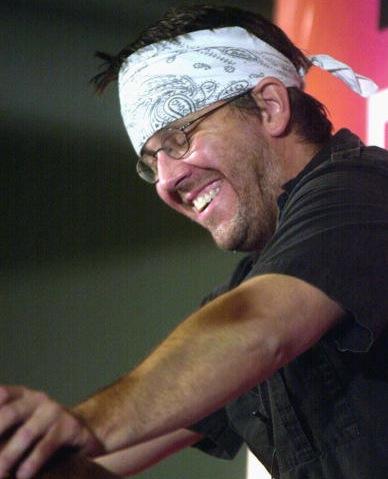

( Getty Images )

BROOKE: This week, the film "The End of The Tour" came out in wide release. It follows Rolling Stone writer David Lipsky as he travels with David Foster Wallace during the last leg of the 1996 book tour for his masterwork, "Infinite Jest." Over many hours in flight and smoke-filled cars around the frozen Midwest, Lispky recorded their wide-ranging conversations. They discuss everything from the role of fiction in modern society to the seductions of sudden celebrity to well, Baywatch.

TAPE:

DAVID FOSTER WALLACE: I don’t think writers are any smarter than other people, I think they’re maybe more compelling in their stupidity or confusion.

BROOKE: But when Lipsky returned, Rolling Stone quickly redirected him to a breaking story, so his tapes gathered dust for 12 years. Until David Foster Wallace committed suicide in 2008. Rolling Stone then pressed for the piece, which Lipsky wrote and it won a National Magazine Award, and then he followed up with a book called "Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself," composed largely of the tape transcripts. "The End of The Tour" is based on that book. Jason Segel plays Wallace and Jesse Eisenberg, Lipsky.

TAPE:

SEGEL as WALLACE: You’re like a nervous guy, huh?

EISENBERG as LIPSKY: No no no no, I’m okay, how are you?

SEGEL as WALLACE: 'Cause I’m terrified.

EISENBERG as LIPSKY: Are you?

SEGEL as WALLACE: Yeah, so you’re not alone in this. We’ll do this together.

EISENBERG as LIPSKY: I think it’s gonna be a lot of fun.

BROOKE: David Lipsky, welcome to On the Media.

LIPSKY: It's great to be here, Brooke, thank you.

BROOKE: So, let's go back to 1996. Wallace's thousand page "Infinite Jest" has just made him an instant literary rock star, New York Magazine's Walter Kirn says it's locked up the National Book Awards. Now, Rolling Stone hadn't done a profile of an author in 10 years, the movie shows you pushing for the assignment.

LIPSKY: But in real life, Jann Wenner saw a review in the New York Times and he saw that David Wallace had a bandana and long hair and he said, Ah, he's one of us and Lipsky.

BROOKE: (laughs) You arrive and one of the major themes of your talks together is trust. He seems painfully concerned about how he's coming across, and how you'll ultimately depict him. And we have a clip of it from the movie.

TAPE:

SEGEL as WALLACE: I'm sorry, man.

EISENBERG as LIPSKY: What's wrong?

SEGEL as WALLACE: It's just, you're gonna go back to New York and like, sit at your desk and shape this thing however you want and that, I mean, to me it's just extremely disturbing.

EISENBERG as LIPSKY: (laughs) Why is it disturbing?

SEGEL as WALLACE: 'Cause I think I would like to shape the impression of me that's coming across. I don't even know if I like you yet. So nervous about whether you like me.

LIPSKY: When I hear it in my ears, which is the way that I listened to the tapes, it always sounds like him. Which --

BROOKE: Jason Segel.

LIPSKY: Yeah. When I came across that sentence in the transcript, after his death, when he was saying that he wanted to be in control of how he was coming across, that was how I decided to do the book and it's kind of the way they decided to do the movie, too, which is: just let him tell his own story.

BROOKE: And yet, in a book, you have to read it. Wallace says that a quote is different when it's transmuted onto the page.

TAPE:

DAVID FOSTER WALLACE: stuff said out loud on the page doesn't look said out loud, it just looks crazy.

(Both laugh)

BROOKE: Stuff said out loud on the page doesn't look said out loud, it just looks crazy.

LIPSKY: He is one of the only writers that I've ever talked to who, when he talks, talks in his prose.

BROOKE: So --

LIPSKY: He was wrong. I mean, he's extremely smart, but he was wrong about that.

BROOKE (laughs)

LIPSKY: It was a great thing. Rather than having to say, here's what I thought he was thinking during high school, just to have him tell his story.

BROOKE: I'm wondering, now that you're watching yourself adapted and depicted on film, how does that feel? Jason Segel and Jesse Eisenberg, tense, wary, depicting you and Wallace in a ring, dancing around each other, not necessarily trying to land punches but trying to avoid them.

LIPSKY: Jesse and Jason in the movie, they're both young men and they're trying to decide what they want their lives to be about. And they have different perspectives on that. I think that you have two people who are writers and they're trying to get a sense of who the other person is. And so, there are a lot of ___ ideas you'll throw out to see which one the other person will respond to. So what you're seeing there is reporter tennis.

BROOKE: (laughs) There's another anxiety of his that fills the transcripts: how his sudden success threatens his fragile equilibrium.

TAPE:

DAVID FOSTER WALLACE: I wouldn't be so careful about this kind of stuff if I felt very much confidence that I could handle it well. And I'm aware that this makes very good copy and this will be a neat part of the article, but it's also really, like....you know...I feel like we've sort of become friends and....understand that. I mean, this stuff...it's great, but it's also really scary at the same time. Because I've got what I hope is like 40 more years of work ahead of me.

BROOKE: Pretty heartbreaking, that last line. But, when Wallace says, we've sort of become friends, did you think that was a manipulation?

LIPSKY: No, I mean, when you've talked about "Die Hard" with somebody and its sequels, I think you become friends. And I also think that if you're driving with somebody it's just something that happens after mile 41. Up to mile 40, you can be strangers, or you can be considerate, or seatmates, but at mile 41 you become friends.

BROOKE: (laughs) But there's that scene in the movie where Lipsky -- your character -- goes into Wallace's bathroom, makes notes of what's in the medicine cabinet, and later your Rolling Stone editor asks you to press him on his rumored heroin addiction and you say -- well, here's a clip.

TAPE:

EISENBERG as LIPSKY: Well, what, what am I supposed to say? Is it, is it true you are a heroin addict?

EDITOR: Yes. That's your story.

EISENBERG as LIPSKY: (laughs) Okay well that's, it's, it's hard.

EDITOR: Why? Because you like him?

EISENBERG as LIPSKY: Well, (laughs) yeah. Yes.

EDITOR: David, you gotta press him.

EISENBERG as LIPSKY: Ok.

EDITOR: Be a prick if you have to. You're not his best buddy.

EISENBERG as LIPSKY: I know.

EDITOR: You're a reporter.

EISENBERG as LIPSKY: All right.

BROOKE: How did you thread that needle?

LIPSKY: Um...

BROOKE: At one point he gets incredibly testy. Almost scary. He's a big guy.

LIPSKY: (laughs) He is a big guy. Um, in the book I write that he looks like someone who might invite you to play hackysack and then if you didn't he might consider (laughs) he might consider persuading you.

Brooke laughs

LIPSKY: But, uh, for him to get the attention of Rolling Stone, part of the deal was getting these questions that might be unpleasant, and for me getting the chance to travel with him for five days. The bargain on my side was asking questions that were not fun to ask.

BROOKE: Tell me about that weird conflict over his ex-girlfriend. Now, that's not in the book. I know that as Donald Margulies, the scriptwriter, was reading your book, he noticed an enormous change in the tone. It got quite frosty. But he couldn't find a reason for it.

LIPSKY: Donald's a very smart writer, so he said, When you're coming back from Minneapolis, the tone is very different. Did something happen there? We had been traveling at that point for three days. I think we'd both kind of forgotten what I was doing there, so when I go to talk to a former girlfriend of his, trying to get secondary sources, you know, he just saw a tall person talking to his ex-girlfriend and said, Hey, don't do that.

TAPE:

SEGEL as WALLACE: I saw you hitting on Betsy... You got her to give you her address.

EISENBERG as LIPSKY: (laughs) No no no, I got her to give me her email address in case I had questions about the piece that I am writing about you. Yeah, really.

SEGEL as WALLACE: Well, tell you what. Um -

EISENBERG as LIPSKY: What?

SEGEL as WALLACE: I don't want her talking to you.

EISENBERG as LIPSKY: I will contact her

SEGEL as WALLACE: Look, I told you that Betsy and I dated during grad school. The least -- look at me -- the least you could -- no, you're not -- the least you could do is show me the respect of not coming on to her right in front of me.

LIPSKY: I remember that Jason was talking about the times they shot that and he said that the first time, when he stood up very tall, and Jason's a big man, that when he made that speech, Jesse started crying. So that he had to redo it and do it in a softer way that's in the movie.

BROOKE: Now, prior to that, Wallace spoke to your girlfriend on the phone. You called her, she'd been reading Infinite Jest, he says, Let me talk to her. They talk for 30 minutes, you're watching, it's kind of excruciating.

LIPSKY: She loved his work and so, it's great to be able to call and say, Hey, here he is on the phone. And then there's that other thing which is, when someone you really care about is having more fun talking to someone else, But then it's a mixed thing because it's like, Yes, this guy's great, as I told you, but don't think he's that great.

Both laugh

LIPSKY: Actually I suppose it must have been like, um, his watching me talk to Betsy.

BROOKE: You and Wallace have amazing conversations about pop culture: Alanis Morissette, Steven Spielberg, Greenday, REM, Hansen. There's a moment when Wallace discusses the seductions of entertainment.

TAPE:

DAVID FOSTER WALLACE: We were making jokes about Love Boat and Baywatch and these really, really commercial, really reductive shows that we so love to sneer at are also tremendously compelling because the predictability in popular art, the really formulaic stuff, is so profoundly soothing. it gives you a sense of order, that everything's going to be alright. That this is a narrative that will take care of you and won't in any way challenge you. It's like being wrapped in a shammy blanket and nestled against a big generous tit.

BROOKE: He goes on to say that despite the comforts of popular culture, serious art eventually will out. It's an optimistic thought, he seemed to swing precipitously between two poles.

LIPSKY: I think what he was saying was how I think a lot of people, listeners to this show, will listen to NPR and then when they're in their car they'll also be listening to some great music that puts them in a good mood and that takes care of them. And --

BROOKE: (laughs) Because NPR certainly won't.

LIPSKY: (laughs) It will but NPR will require something of you. It will require that you engage, it will require that you think about your opinion, it will require you to change your opinion. Whereas the other stuff, it allows you to relax. And what he was saying is, you have to do both.

BROOKE: But he tells you that he's a TV addict. In fact, he says it's his only addiction, and then he takes the idea to its logical conclusion. And we have a clip of it from the movie.

TAPE:

SEGEL as WALLACE: So look, as the internet grows in the next 10, 15 years, and virtual reality pornography becomes a reality --

EISENBERG as LIPSKY: Mhm

SEGEL as WALLACE: We're gonna have to develop some real machinery inside our guts to turn off pure, unalloyed pleasure or I don't know about you, I'm gonna have to leave the planet.

EISENBERG as LIPSKY: Why?

LIPSKY (over clip): I love this clip.

SEGEL as WALLACE: 'Cause the technology is just gonna get better and better and it's gonna get easier and easier and more and more convenient and more and more pleasurable to sit alone with images on a screen given to us by people who do not love us but want our money and that's fine in low doses but if it's the basic main staple of your diet you're gonna die.

LIPSKY: At the same time that he was saying that TV can take care of you. He also doesn't have a TV in his house because he doesn't want to be taken care of all the time. What he said was that the basic message you keep getting from TV is that you're stupid. And that there are parts of us that are a lot more ambitious than that. His idea of a challenging book like Infinite Jest is that it would nourish that part of you, too.

BROOKE: Have you any idea how many people who bought Infinite Jest actually finished it?

LIPSKY: I think there's an idea that it's difficult to read, but it's as difficult as reading five 200-page books back to back.

BROOKE: Yeah, but that's how long all the collected works of Douglas Adams' Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy is, but it doesn't scare me.

(both laugh)

LIPSKY: Well, Brooke, was does scare you about Infinite Jest?

BROOKE: (laughs) Ah, I guess because I've spoken to so many people who said they couldn't get through it.

LIPSKY: I think with David's work, one of the things, when you look at his syllabuses, you know, he would teach Stephen King and Mary Higgins Clark. His diet wasn't only the serious stuff. It was also the book equivalent of shows like Baywatch and the old Love Boat. And so the book is written by somebody who knows how to construct a really cool, involving story. So I think it's just length. Books like David Wallace's wake you up. And that's the reason to read them. Because you walk in asleep and then when you talk out, the world is in color.

BROOKE: You two really seem to get each other, and that seemed to create a space for some real candor. Like at one point in the tapes, he says, I've decided that I really need to find a few things that I believe in order to stay alive.

TAPE:

DAVID FOSTER WALLACE: Which means that I have to structure my life, you know, sort of like anybody who's dedicated to something, to maximize my ability to do good stuff...And it doesn't make me a great person, it just makes me a person who's really exhausted a couple other ways to live. And really taken them to their conclusion, which for me was a pink room with no furniture and a drain in the center floor, which is where they put me for an entire day when they thought I was gonna kill myself. Where you don't have anything on and somebody's observing you through a slot in the wall. And when that happens to you, you get tremendous--you get unprecedentedly willing to examine other alternatives for how to live.

BROOKE: One thing that's playing through every viewer's mind when they see "The End of The Tour," and every reader's mind as they read your book, is that he's going to kill himself. How does that not inform every thought we have about David Foster Wallace? And how do you combat that?

LIPSKY: He is the most alive writer of the last 2 or 3 decades. And when you're reading him it sounds the way we flatter ourselves that our brains sound to us. He said a great thing about writing, he said that he didn't thik that writers were smarter than other people. But what they're able to do was sit and clench their fists and think very hard about the stuff that we only think about occasionally in our daily lives. When the writer does her job write, she wakes the reader up to stuff the reader was aware of all along. That is what he was like as a writer. When someone is a suicide, we often will begin to read their work entirely through that grey lens. And when I sat down to think about this book, what I wanted to show is, hey he is not just a very alive writer, he is the most alive person that I spent time with, and that's who he was. He's not just someone who, when he was 46, ended his own life.

BROOKE: Thank you very much.

LIPSKY: It's been great to be on, Brooke. I wanted to hear more clips. (laughs)

BROOKE: Well, we have --

LIPSKY: No, I didn't, no

BROOKE: Well, we have one more.

LIPSKY: Okay, please, yeah.

BROOKE: Let's play it.

TAPE:

SEGEL as WALLACE: I'm not so sure you want to be me.

EISENBERG as LIPSKY: I don't?

SEGEL as WALLACE: Give my best to Jann.

LIPSKY: (laughs) That's great.

BROOKE: Did he say that?

LIPSKY: No, he didn't say that.

BROOKE: Mhm.

LIPSKY: What he said before we left was that ambitions for ourselves can be great, they can be motivating, they can be a flamethrower held to our ass, but past a certain point they can be toxic. You know, what he was saying was, that that actually is what happens when you get what you want.

BROOKE: Did any of that stuff stick with you?

LIPSKY: We never saw each other again. And part of it was that he was a much more successful writer than I was, and I was always afraid that if I went and emailed him or tried to call him or talk to him that that would always be there. And one of the things he had said was that it'd be interesting to talk to me again in a few years when I'd had some of the experiences he'd had. And so I'd always waited. And then when that time came, um, you know, I would write emails saying, I would like to have that conversation now. And there's a thing that I do when I'm unsure about an email, is I take the actual address off and I email it to myself to see how it looks, and I would get these emails and I would think, that looks like a crazy person wrote it. So I never sent them.

BROOKE: David, thank you very much.

LIPSKY: It's been great being here, Brooke. Thanks for having me.

BROOKE: David Lipsky is a contributing editor to Rolling Stone and the author of "Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself," among many other books, including "The Art Fair."