"Busted" #2: Who Deserves To Be Poor?

( AP Photo )

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I'm Brooke Gladstone, with Part 2 in our series, “Busted: America’s Poverty Myths.”

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

This time, the theme is personal responsibility. So, to get you situated, how about a thought experiment? Think about a really bad decision you made. Now imagine having to pay dearly for every mistake you ever made. Now, imagine living on a margin of error so slim that a dead car battery throws your life into chaos and ruin, how much would you plan for the future? And finally, consider the famous 1972 Stanford Marshmallow Experiment in which a series of kids were faced with a choice, one treat now or two treats later. The kids who opted to wait ended up doing better in life. They had will power. You’ve done okay, so you must have it too. Poor people, maybe they just don’t have it, right?

[UNIV. OF ROCHESTER CLIP]:

EVELYN: Do you know what? It is snack time now.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Well, 40 years later, the University of Rochester redid the experiment, with fewer kids but with an intriguing twist. Before posing the marshmallow question, a researcher told each kid that he or she could play with a jar of blunt and broken crayons now or hold out for a big fresh set later. After a pretty lengthy wait, half of the kids got the big fresh set. Their expectations proved reliable, so they were dubbed “the reliables.” The other half, “the unreliables,” got, - oops, don’t have it, just use the crappy crayons. Then, the researcher sprung the marshmallow test.

[CLIP]:

HOLLY PALMERI, ROCHESTER BABY LAB MANAGER: Look what I’ve got.

EVELYN: A marshmallow!

HOLLY PALMERI: Yeah. So wait, just a second, let me explain. So you can either eat this one marshmallow right now or, if you can wait for me to go get it from the other room, you can have two marshmallows, instead.

EVELYN: I want two marshmallows.

PROF. RICHARD ASLIN: And what we found, which was an incredibly large effect, the children who were in the unreliable group were more likely to fairly quickly pick up the marshmallow and eat it. So, on average, they waited about three minutes.

EVELYN: And did you know that I did not eat this marshmallow yet?

PROF. RICHARD ASLIN: The children who were in the “reliable” group waited four times longer

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The unreliables instantly internalized the idea that one bum steer begets another. That's what poverty does to you. As Linda Tirado wrote in Hand to Mouth: Living in Bootstrap America, “We don't plan long-term because if we do we'll just get our hearts broken. It's best not to hope. You just take what you can get as you spot it.”

So why tell you this now? Because researchers find that middle-class people assume that poor people lack personal responsibility. It's a very old idea.

[CLIP]:

LEONARD GOODWIN: In my study, it shows that middle-class people tend to misperceive the work ethic of the poor.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Leonard Goodwin of the Brookings Institution interviewed thousands of poor and middle-class people and discussed his findings on CBS in 1972.

[CLIP]:

LEONARD GOODWIN: And the basic finding is that the poor are as strong in the work ethic as the middle class. They identify their self-esteem, their self-respect with work to the same extent as the middle class.

WOMAN: Well, there are a lot of people that are saying that one of the reasons that they fail is because either they don't want to work or because they’re lazy.

LEONARD GOODWIN: Well, this just isn't so. These people do want to work and many of them have worked. And what’s really stacked against them are the odds of being able to obtain good jobs and have the health facilities and other things that can keep them in the job.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In fact, nearly three-quarters of the people enrolled in America's big public support programs are members of Working Families, including roughly half the people who work in fast food, home care and child care. As for the jobless, many can’t began to pay for the training, the day care, the transportation, the clothes that work demands. And, oh yeah, there are still more applicants than jobs. But I get ahead of myself. I need to talk to someone in that situation.

So where's poverty central? Kathy Edin, Johns Hopkins University sociologist and co-author of $2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America, gave us directions.

KATHY EDIN: If you sit outside the plasma clinic on West 25th Street in Cleveland, you’ll see busload after busload of people get off at that stop.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Our producer Eve went in February. It was freezing. People weren’t eager to talk, but she found a room in a church nearby, offered a bus voucher – yes, we did that - for a talk, and she found Carla, who needed the bus voucher and, it turned out, also needed to talk.

CARLA SCOTT: Well, my name is Carla Renee Scott. I'm 30 years old and I’ve been a resident of Cleveland, Ohio all of my life.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: She was trying to sell her plasma for bus fare to the hospital, where she spends each day with her severely premature baby, Kaylee.

CARLA SCOTT: She’s been through four surgeries already. At 23 weeks, she's only one pound and she had two perforated holes in her bowel. She now has two stomas on the side of her stomach that’s out with colostomy bags. But she's doing better. She's a fighter but thinking about doctors for her once she – she’s actually able to come home, setting up the Social Security and things like that, those are the things that I have to deal with long term. I’ve been doing a lot of footwork with that, still looking for a job.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Eve kept prodding, gently, for details about Carla’s day-to-day life and it started to get to her a little.

CARLA SCOTT: I can’t, I can’t even – it’s – there are so many days like that. Every day, all you think about is the safety of your child. You know, you worry every day. It’s just so weird to even be able to express it because I’ve been like robotic. I just keep going and I don't talk about it. So I'm sorry that I'm a little bit emotional. I’m just finally being able to process it. I’ve always been the type of person when put [SNIFFLES] in a situation I try to champion through it, but this one right here is just - it’s very difficult. And – the last thing I ever wanted to do was sell my plasma, but if I have to go to a plasma center to at least have fare to go back and forth and change my clothes or just to eat, then that’s what I’m gonna do to be there for her.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It’s 20 to 50 bucks per donation, depending on your weight, and takes about 90 minutes. After that, you can feel pretty weak. Plasma’s a $14 billion business this year, growing fast. And the US provides 65% of the world’s supply, with clinics proliferating where poverty prevails – too metaphorical, right?

CARLA SCOTT: I can't stand needles. To have a needle in you taking the nutrients and everything that you have in your body and then pushing blood back into you and repeating the cycle, sucking all of this life out of you and, you know, you’re looking at it like, wow, this is a big container. I’m not that big of a person. Ugh, it, it’s so many different feelings from it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: When Carly got pregnant, she had a plan, a job and a steady boyfriend. But with Kaylee born so early, so fragile, so needy, he just couldn't stick. How upsetting was that?

CARLA SCOTT: My whole everything changed. I have never had a problem with unemployment, finding a position. And here is the thing. Does it upset me? Yeah, it upsets me but I am that person that takes responsibility for their actions. Are you responsible for me being pregnant? Absolutely not. So it is within my realm to ask for help, if I can receive help momentarily, and then get up on my feet and continue to go. I mean, yes, you’ve just seen me sad about it because it was unexpected; it was not in the plan. But feeling sad and feeling sorry for myself is not gonna help the situation, is it? I mean, if I seen you guys out there and walked up to you and asked you for a couple of bucks just to get on the bus, I have to have the expectation that you might say no. That’s just everyday life. So would I sit up there and feel sorry for myself and look for a handout or do I advocate for myself and be proactive and go sell my plasma, like I did?

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So how did we get to this point? Where, you might ask, is welfare? Well, $2.00 a Day co-author Kathy Edin would say that welfare is dead, 20 years dead, with the passage of Bill Clinton's Welfare Reform Act. We’ll get to that later. But first, to understand how welfare died, we have to go back to its birth 150 years ago, which Edin says was a bit of an accident.

KATHY EDIN: In the aftermath of the Civil War, there were a lot of widows and various states set up mothers’ aid programs to keep children with their mothers so mothers didn't have to send them to orphanages.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: These mothers’ aid programs puttered along until the Great Depression, when states couldn't afford to pay for them anymore. Enter FDR.

KATHY EDIN: As part of the Social Security Act of 1935, the federal government took over responsibility for these widows through a little program called Aid to Dependent Children.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This was the nation's first federal cash assistance program for parents, borne of the belief that widows should be able to stay home with their kids. It was supposed to be small, a stopgap measure. Instead, it grew. Divorced and never-married women signed on. In the late 1930s, there were just a few hundred thousand recipients. By 1962, there were 3.6 million. And meanwhile, states drew their own distinctions between the deserving and the undeserving poor.

[MUSIC OUT]

KATHY EDIN: So oftentimes, they would engage in practices that essentially capped black women, people of color and never- married mothers from receiving benefits. Sometimes caseworkers would don white gloves, for example, and they would impose good housekeeping tests by running their fingers across the fireplace mantel to see if they picked up any dust.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So people could be disqualified for being black or unmarried with children or having a dusty house.

KATHY EDIN: They gave caseworkers a huge amount of discretion. They initiated midnight raids of single mothers’ houses and if they found evidence of a man - a razor on the sink or a belt in the bathroom - they would disqualify the family. So these were discretionary tools that states used to include certain groups and exclude other groups. It was a sort of social redlining.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But quietly. During the long postwar boom, the media barely covered poverty, black or otherwise, In fact, historian Martin Gilens found that Time, Newsweek and US News & World Report each ran only about 16 stories about poverty for the entire decade of the ‘50s. But in 1958, John Kenneth Galbraith wrote a scathing critique of the oblivious upper class in The Affluent Society, followed in 1962 by Michael Harrington's The Other America: Poverty in the US, a kind of exposé.

KATHY EDIN: About these hidden groups of people who had been left out of the economic expansion - the elderly, Native Americans, both rural and inner-city African-Americans, the Appalachian region, and so on. Harrington showed up to 50 million Americans were poor.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Nearly a quarter of the population.

KATHY EDIN: How could it be? You know, it was almost like the nation's conscience was pricked. And it really says a lot about who we thought we were then.

[CLIPS]:

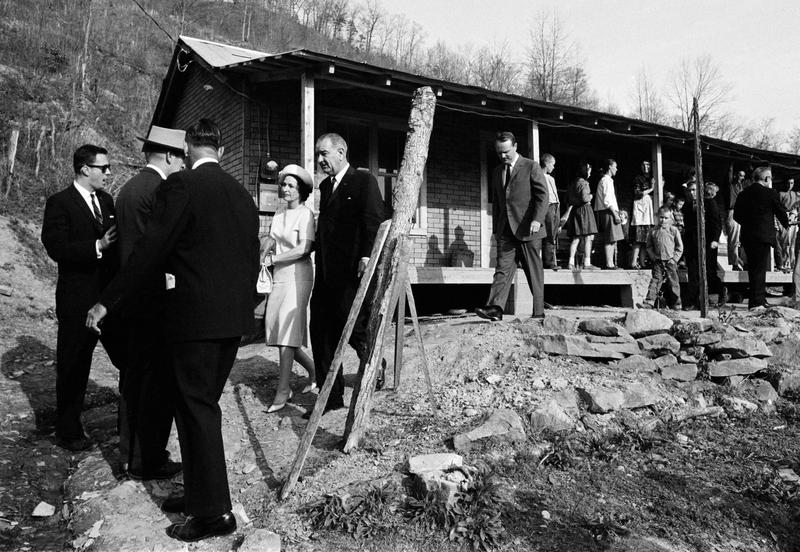

PRES. LYNDON B. JOHNSON: Our task is to help replace their despair with opportunity.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: President Lyndon Johnson's 1964 State of the Union address.

PRES. JOHNSON: And this administration today, here and now, declares unconditional war on poverty in America.

[AUDIENCE APPLAUSE]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It would be his legacy and the crowning achievement within the American century.

PRES. JOHNSON: The richest nation on earth can afford to win it. We cannot afford to lose it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Johnson's efforts resulted in improvements to Social Security, a permanent food stamp program, increased federal funds for free breakfasts and lunches for poor schoolchildren, the Head Start Program, Medicaid, Medicare, and the number of people receiving cash assistance, now called AFDC, grew from 4.2 million in 1964 to 11.3 million in 1976. As welfare swelled, so did our aversion to it.

KATHY EDIN: Even Franklin Delano Roosevelt called welfare a narcotic, a subtle destroyer of the human spirit. So welfare and America just have never gone together. But these fears about welfare sapping people of their initiative and creating a permanent dependent class really began to be stoked when white middle-class moms went to work. You had a whole group of people on welfare and their claim to legitimacy is that they were mothers and mothers ought to stay home with their children. That's why the program was invented. So suddenly, white middle-class women start working and poor women no longer have a moral claim that government should pay them to stay home with their kids.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I never would have expected a woman's choice to work outside the home would disrupt public opinion about the benefits of poor women who have no choice because there isn’t anyone to take care of their kids.

KATHY EDIN: Yeah, very interesting. Americans really became convinced that the very programs that we had invented to care for the poor were actually making poverty worse.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Ronald Reagan campaigned against welfare in 1976 on the notion that taxpayers were well-meaning chumps to pay for it, and his Exhibit A was an infamous reprobate the Chicago Tribune had dubbed “the welfare queen.”

[CLIP]:

RONALD REAGAN: She used 80 names, 30 addresses, 15 telephone numbers to collect food stamps, Social Security, veterans’ benefits for four nonexistent deceased veterans’ husbands, as well as welfare. Her tax-free cash income alone has been running $150,000 a year.

[AUDIENCE RESPONSE]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Reagan's “welfare queen” was modeled on Linda Taylor, a suspected kidnapper, baby trafficker and murderer who eventually was sent up the river, a distinctly atypical welfare recipient who, by the way, was typically white.

[AUDIENCE APPLAUSE]

RONALD REAGON: My friends, some years ago the federal government declared war on poverty and poverty won.

[END CLIP][MUSIC UP & UNDER]

So, marching from the Civil War to FDR, to Johnson, to Reagan, the next, actually, the last stop on the welfare parade is Bill Clinton who, in a 1991 campaign speech sounded like many who’d preceded him.

BILL CLINTON: In my administration, we’re going to put an end to welfare as we have come to know it. I want to erase the stigma of welfare for good by restoring a simple dignified principle. No one who can work can stay on welfare forever.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Clinton was skilled at co-opting the right by embracing some of its precepts, and welfare was ripe for reform. The ranks were growing and poverty deepening. Moreover, it didn’t encourage mothers to seek work, since their already stingy benefits shrank with every low-wage dollar they earned. So Clinton tapped the ideas of Harvard Professor David Ellwood, who had access to the first big data set that could determine how long most people actually did stay on welfare.

KATHY EDIN: The vast majority of welfare recipients were really moving in and out of the labor market and on and off of welfare. The average spell was only two years. So he went on The Oprah Winfrey Show. He wanted to tell this story, hey, it’s not as bad as we think. You know, we think of welfare as creating this long-term dependency, but, but, look folks, it really is, for most people, a hand up and not just a hand out. The show sort of erupted in mayhem. There was actually a fight offstage, caught on camera. Ellwood concluded that it was the world's worst job to be a defender of welfare, [LAUGHS] so he went back to his office and he said to himself, how can we sustain a program that is obviously so fundamentally unmoored from American values?

He determined that welfare had to be replaced, not just reformed, and he said to himself, what group of people are really poor and are playing by the rules but are not getting any kind of government support? The working poor. So he said, what can we do for the working poor because what we really want to do is drew more welfare recipients into the workforce? How can we make the lives of the working poor better?

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So Ellwood came up with a plan, 1) radically expand a little-known program called the earned income tax credit, which was basically a pay raise for the working poor, and 2) impose time limits requiring recipients to work after a few years of receiving cash assistance. If you couldn't find a minimum wage job before your time limit expired, the government would provide one. Presto, welfare was thus melded to the American work ethic.

KATHY EDIN: Clinton heard him give this paper at a conference. Reportedly, he rushed the stage.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Clinton brought Ellwood into the White House to write up his plan, but then?

[CLIP]:

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Republicans are now the majority party, both in the Congress and in the governors’ mansions across the nation. The only powerbase the Democrats still have is the one that was not at stake yesterday, the presidency itself.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Having swept both houses in the midterms of 1994, Republicans started passing their own versions of welfare reform. Ellwood, horrified, resigned in 1995. Clinton vetoed two of the Republican bills and finally, in an election year bow, signed one, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, Clinton's welfare legacy.

KATHY EDIN: The Clinton version of the program had all kinds of protections to make sure people wouldn't fall through the cracks - guaranteed jobs, support in, in finding work, childcare, and so on. What the Republicans did is sort of strip all of those protections away. Both plans had time limits and work requirements, but there was no sort of guarantee of a job, no protection if you couldn't find work, let’s say, in an economic downturn.

The other thing that was really different about the Republicans’ approach is that the program got block granted to states, with very little oversight.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: States can use those block grants, called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF, any way they like, to pay for a program the state is already funding or to subsidize private businesses, like daycare centers. Some states just hoarded the money. And the fact is the law offers states incentives to make sure that those funds, called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, never actually make it into the pockets of needy families. Here's how.

The law says that states must ensure that half of their TANF recipients are working, which takes effort, you know, training programs, and so on. But the law also says that states don't have to meet that 50% target, if they shrink their welfare caseloads. So many states just take the simplest route and erect elaborate barriers to keep families from being enrolled. Many are simply told, falsely, that they’re not eligible, and that's why fewer than a quarter of America's impoverished families receive cash benefits, according to the Progressive Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. In Texas, it's only five poor families out of a hundred. In Louisiana, it's four.

One more thing, the $16.5 billion allotted for cash assistance in the 1996 act was not tied to inflation. It's still 16-1/2 billion, but it's worth less and less each year. And the principle that FDR cited, that Johnson worked on, that America has a moral obligation to ensure that no one goes without food or shelter, that died.

[CLIP]:

PRES. BILL CLINTON: After I sign my name to this bill, welfare will no longer be a political issue. The two parties cannot attack each other over it. Politicians cannot attack poor people over it. There are no encrusted habits, systems and failures that can be laid at the foot of someone else. We have to begin again. This is not the end of welfare reform, this is the beginning. And we have to all assume responsibility.

[AUDIENCE APPLAUSE][END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Initially, Clinton's reform bill was cheered. Child poverty rates fell, single mothers left welfare for work in huge numbers. But ultimately, many have left or lost those jobs because without sufficient support for training or rent or child care or medical care, they can't make it. And yet, many are not on welfare, either because their time limit – in Arizona it’s just 12 months - expired and they can't reapply, or they can’t make it through the arduous application process, or they don't even know it exists, or, says Kathy Edin, because of the stigma.

KATHY EDIN: Once moms went to work in the formal economy, they liked it. There was a sense that rather than being a stigmatized welfare recipient who politicians mocked and ordinary citizens shunned, you were suddenly a, a worker, a taxpayer. You were part of society in an entirely different way. To go on assistance when you saw yourself as a worker was an anathema to people and people really actively began to shun the rolls.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Hence, what Edin calls the $2.00 a day poor. Many dispute that $2 number because it doesn't account for non-cash benefits, like health and housing assistance and food stamps and the fact that many poor people underreport their earnings. But the fact remains that with TANF funds so often diverted or withheld by states, the poor often have no access to cash. So they scavenge at scrap yards, sell food stamps or sex or plasma.

That said, when Clinton arrived, welfare desperately needed reform and his did work, for some. The earned income tax credit gave many of the working poor a crucial boost.

KATHY EDIN: What has changed about the poor is how different they are from one another, some capitalizing on changes to the safety net, which really lift them out of poverty, and others falling through a hole in the safety net that has been created by this block grant system which siphoned money away from the poor and made the promise of cash aid an illusion.

[MUSIC/MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Coming up, what Carla’s 90-year-old grandmother Grace thinks about welfare.

GRACE SCOTT: I worked 12-1/2 years, seven days a week to pay for this house. You can keep welfare, as far as I was concerned.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media.

[PROMOS][MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I’m Brooke Gladstone. Continuing with “Busted: America's Poverty Myths.”

A recent poll conducted by the LA Times and the conservative American Enterprise Institute finds that roughly 87% of Americans, including 81% of those below the poverty line, believe that requiring poor people to seek work or training in return for benefits is better than providing aid without asking for anything in return. And that’s pretty much what we found as we hopped from Cleveland to Appalachia to Columbus on our poverty tour.

Obviously, the poor are no more monolithic than the rest of us, and we didn't talk to anyone who didn't want to talk to us. But we did get a multigenerational take when we followed up with Carla a few months after that meeting at the plasma center. And she invited us to the home of her grandma, Grace, who’s 90.

CARLA SCOTT: Oh, we should close the front door.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It’s a dicey neighborhood, lots of gunfire, says Grace, and very little that’s green. But it's a comfortable old house, with good bones, purchased long ago with the help of a Federal Housing Administration loan. Our conversation was both meandering and illuminating. I asked Grace why she thought people were poor, and she took a very hard line on the people around her.

GRACE SCOTT: I think a lot of it is laziness. If they don’t make $15 or more an hour, they really don’t work. I worked 12-1/2 years, seven days a week to pay for this house. You can keep welfare as far as I was concerned. [LAUGHS]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But you were grateful to Roosevelt. Were you grateful to –

GRACE SCOTT: Well, my Social Security is what I’m working for, my 22 years of working, thank you. [LAUGHS] That’s my money. They’re now givin’ me only my money back that they’d take out of my check every time I worked. It’s not a gift. I’m proud of myself. Well, I was always taught if you’ve got a job, you have more in your pocket than you had before you went and got that job. Why sit at home and grumble ‘cause you ain’t got nothing but you don’t want to work for low wa – for low pay?

CARLA SCOTT: If I had a choice to not be on welfare, would I be on welfare? No. But now it’s definitely a help. Now, do I agree with the fact that they should pay more? Yes. I was a aide and being a home health aide, well, you’re going to someone and you’re cleaning their bottoms. You’re basically doing the same functions that you do for yourself and you’re only getting paid $8, 9 an hour. I think that's a little bit terrible. Who will w - be motivated to go to work, knowing that you have to literally pick someone up, feed them, bathe them, clothe them, wash them, move them, give them their medication. You do a lot. You should be compensated for that, especially if it's a trade or especially if is something that you went to school for. You’re working 10, 12 hours a day at a place that’s paying you 8.10 an hour, biweekly. You don't even have gas money to make it, and by the time you get paid, all your bills that come, comes out of that, and you don’t have enough gas money. This is why people are gonna sell their plasma.

And another thing, back in those times, you had more family- oriented people that would help out with watching children. Now, some women do have to sit at home ‘cause they don’t have that anymore, and then you have that fear of taking your child to put ‘em in daycare and not knowing what's gonna happen to ‘em. So I do understand a lot of mothers wanting to work from home, ‘cause I want to do that.

KATHY EDIN: You know, there are a lot of studies that suggest that most people would prefer to work.

GRACE SCOTT: They’re taking care of people that’s on drugs.

KATHY EDIN: Do they not deserve to live?

GRACE SCOTT: But nobody force you to take drugs. If they can stay out – take their drugs and get a check every month, they buy more drugs. I see it around here, so I know what I’m talking about.

CARLA SCOTT: And what is disheartening is people that do work hard, we don't have the programs to assist anyone to get back on their feet. Knowing that I have to come home with my daughter, the only programs I come into is the programs to help and assist people on drugs and things like that. But there’s not a lot of single mothers’ programs, you know?

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What kind of programs do you think would help you get back on your feet?

CARLA SCOTT: Educational programs, so they can just further themselves, even if it's a trade. There’s no programs out there, like transitional housing. I know they have Section 8 programs, but the Section 8 program in Ohio has been backed up for over five years. And if you do win the lottery, you have to wait another five years. But some people are homeless now. But there’s people that’s been on food stamps for generations and generations and they go stand outside of grocery stores to try to sell the food stamps to you, and that’s wrong when there’s people who really, really need the food and they’re just going through a pivotal moment in their life. Even if I say, okay, can I be on there for a month or receive services for a month, I’m on seasonal break from my job or I just lost my job, it doesn't have to be that long, just for some type of assistance – there’s people that’s been on there since birth.

GRACE SCOTT: That’s the thing of it, is you see so many people using the system for their own personal get-high habits, and I don’t feel like -- the way I worked out, me working two jobs a day for 12-1/2 years -- I don’t feel sorry for ‘em.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: How do you feel about Carla being on public assistance?

GRACE SCOTT: Well, Carla has been to college but Carla didn’t stay in college. That’s the thing of it is.

CARLA SCOTT: Well, I would never lie and say I wasn’t depressed, extremely depressed due to a lot of loss.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Tell me when things started going south.

CARLA SCOTT: Well, everything went south when my mom passed.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: How old were you?

CARLA SCOTT: Twelve years old.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Can you tell me about that?

CARLA SCOTT: Well, I –

GRACE SCOTT: She went through a lot. And when her mother died, she found her mother, and she ain’t got over it yet.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Was she sick?

CARLA SCOTT: No. She was born with a heart murmur and she died of a massive heart attack. When I came in that morning, I had a, a softball game, went to go wake her up for her to take me and she was unresponsive. Tried to do CPR multiple times, and once we called EMS they came, got her and she died in the hospital, so –

GRACE SCOTT: Then her older sister was in charge of her.

CARLA SCOTT: But I was a ward of the state. I stayed with my sister. She was my guardian and then something happened. Well, I’m – I, I – she went to jail and then I was sent to my aunt. I was sent to another aunt, and then I eventually ended up with my grandmother. And then, at that point, because she was older, they decided to emancipate me and give me my own apartment. So they gave me enough time to graduate from high school and as soon as I graduated I had to resume the bills myself.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So here you are, on your own, and you manage to get to college?

CARLA SCOTT: When I graduated from high school, I did go to Tri-C and I accumulated some credits. You have to understand that the program that I was in, Independent Living, were paying the bills. So, you know, I was just used to not paying bills. So having a support system getting through college or going to work plays a very pivotal role. Now, granted, I started working when I was 15 years old, so I did have a job. I have several trades up under my belt.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What is the skill that you have under your belt?

CARLA SCOTT: I am a certified nursing assistant, I'm also a certified medical secretary, and then also I'm certified in bartending.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Why can’t you get a job?

CARLA SCOTT: Now, here’s the thing, it’s not that I can't get a job, it’s the fact that I just had a premature baby [LAUGHS] that requires a lot. And she had over nine surgeries. And when I go to apply for a job, I’m terrified ‘cause I have been called to come back in to consent to surgeries or consent to something that's going on. That's when I decided to get day-to-day money, because it’s not an obligation. And once I get hired on somewhere, it’s 90 days before you even get vacation time or sick leave or things like that. And when I have to leave, I have to leave for her. And I'm in a pivotal moment ‘cause when she getting ready to come home within the next month or two, I’m beating the streets trying to find programs that’ll help me. I mean, the most that I've learned is I would have to literally go to a homeless shelter and then see if they have a program that’ll help assist to pay my rent up because I can't even put her in daycare because she has a high risk of catching infections. She has E. coli now and I don’t even understand how she got that in the hospital.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You’re too young, way too young, to remember Ronald Reagan and the, the welfare queen concept, but do you remember it, been -

GRACE SCOTT: I wasn’t paying too much attention to Ronald Reagan. I’ll tell you my presidents I love. There’s Carter down in Georgia. And I liked Clinton, though he was a little flakey. [LAUGHS] I like him. I didn’t care for Reagan ‘cause of what he did to his wife.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What Ronald Reagan did to his wife?

GRACE SCOTT: He left his wife to marry Miss – the one that just died about –

CARLA SCOTT: Oh, Nancy.

GRACE SCOTT: He was a snake in the grass.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Hey, what about what Clinton did to his wife?

CARLA SCOTT: She’s still with him, isn’t she? She, she must like for him to play around. [LAUGHS]

[LAUGHTER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What about Kennedy?

GRACE SCOTT: I liked the Kennedys. But I know he made his money on bootleg liquor from Ireland. You know, I know [LAUGHS] ‘cause I follow the Kennedys. But the Roosevelts was always rich. I liked them too. I like people with money. [LAUGHS]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You don’t remember Hoover, do you?

GRACE SCOTT: You better believe it. I couldn’t stand the guy, [LAUGHS] ‘cause I’ve seen men, whole lines of men standing in the churches for food. Rich people was killing theirself because of their money. Nnh-nhn [NEGATIVE], no, I don’t like Hoover. He made the rich poor.

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

CARLA SCOTT: Okay, but what about the poor people?

GRACE SCOTT: They were poor too.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Do you care more about the rick people than the poor people?

GRACE SCOTT: No, I’m just telling what they lost. We didn’t have nothin’ to lose, didn’t have nothin’ to lose.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But with 12 children, Grace did have a lot to lose. And now Carla, left on her own for so much of her life, feels she has everything to lose.

Jack Frech, who spent more than three decades as a welfare director in Appalachia, says that is what the comfortable seem determined not to comprehend.

JACK FRECH: I think the most heinous thing, the most heinous thing that we do about poor people is that we don’t accept that they love their children every bit as much as we do. They start talking about poor people being lazy, poor people not wanting to work, poor people not taking care of their kids. Poor people love their children every bit as much as you love your children and I love my children, every bit as much. And they suffer greatly to watch their kids do without.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Okay, so let's address the issue of personal responsibility head on. Why did Carla, so smart, so practical, choose to have a child? Why do some young single mothers on welfare keep having children? Where’s personal responsibility? There are a lot of studies on this.

For one thing, they find that marriage is declining across all income levels and that, in fact, it doesn’t really help the poorest families much if their income keeps them mired in poverty. But as far as babies are concerned, women who can see ahead to college and a future have fewer kids and wait longer to have them because they are primed to wait and to plan. Remember that Marshmallow Test? Here it is, kids. Take it now, a little sweetness in a bitter life.

But there's another reason poverty impedes long-term planning, lack of bandwidth, same reason drivers on cell phones crash more. The Journal of Science found that the stress of poverty imposes a massive cognitive load on the brain. You miss things. You make more mistakes. It’s not about IQ, one researcher told The Atlantic. It’s the context you inhabit. In other words, it could happen to any of us.

[CLIP]:

CARLA SCOTT: My Kaylee is premature.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Carla showed me a video of her baby Kaylee.

CARLA SCOTT: Yeah!

[END CLIP]

I mean, why do any of us have babies? Unconditional love, fulfillment, maybe a chance to provide what you yourself were denied.

CARLA SCOTT: I’m there each and every day, helping with her hands-on care and I’m talking to her. I’m reading books, playing lullabies, just for the mental development of her, reading as much as I can. She is what keeps me going. I can say, hey, your momma’s here, can you smile for your mama? She’ll just smile. What does it mean? It, it means that I can be someone's role model. I can be someone’s protector. I can teach someone. I can love someone. I can teach someone how to love. Oh my goodness, just – the things that I've been through in life, I have the capability of providing something to help this young person grow into whomever they want to be.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Grace told me approvingly that Carla, at 30, waited the longest of any of her granddaughters to have a child. Grace herself had 12. She was married when she had them but seems to have raised them on her own, working day and night, with the help of extended family, stable neighbors and, let’s face it, low expectations. Carla has none of those things but, if her mother’s death derailed her ambitions, Kaylee has put them back on track. She knows she can do this. She’s aching to do this.

CARLA SCOTT: I was happy that she came out of Martin Luther King's birthday. I said, hey, maybe she has a dream, you know? I could be raising the next president, you never know, so – [LAUGHS] you never know. The, the things that I think about is, is just limitless.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Before the 1996 Welfare Reform Act, federal programs supported more than 600,000 welfare recipients working toward four-year degrees. Now, it's only about 35,000. For most, there's, at best, fleeting support for training and then you must get a job, any job. And even if that weren’t so, most colleges can’t cope with poor students - their food stamps, childcare, homelessness. All that almost ensures you will stay poor and your kids will be poor too. Failure appears to be wired into the system. In such an affluent nation, it seems like there’s plenty of personal responsibility to go around, no?

[MUSIC/MUSIC UP & UNDER]

Next week, we take on a myth that goes all the way back to Benjamin Franklin who made a fortune making paper out of rags.

WOMAN: Franklin gets the license in Pennsylvania to print paper currency, so Franklin [LAUGHS] literally turns rags to riches.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: From Benjamin Franklin to Horatio Alger, the enduring ideal of upward mobility is scrutinized and the fateful role of luck revealed.

MAN: So if you come to America with nothing and you play by the rules, you work hard, you get discipline inside yourself –

MAN: Right.

MAN: - you marry and have children, in that order, okay, you do all of those things, you play by the rules, you will make it in America, and luck has nothing to do with it.

MAN: That’s not true, sir,

MAN: I am insulted by what you said.

MAN: Well, that’s [ ? ]

MAN: You are going against the American dream.

MAN: I’m not!

BROOKE GLADSTONE: A wake-up call on the next On the Media.

“Busted: America’s Poverty Myths” is produced by Meara Sharma and Eve Claxton and edited by Katya Rogers, with special thanks to Nina Chaudry and WNYC’s archivist Andy Lanset. This series is produced in collaboration with WNET in New York as part of “Chasing the Dream: Poverty and Opportunity in America.” Major funding for “Chasing the Dream” is provided by the JPB Foundation, with additional funding from the Ford Foundation.

BOB GARFIELD: That’s it for this week’s show. On The Media is produced by Alana Casanova-Burgess, Jesse Brenneman, Paige Cowett, Micah Loewinger and Sara Qari. We had more help from Leah Feder, and our show was edited – by Brooke. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Casey Holford.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Katya Rogers is our executive producer. Jim Schachter is WNYC’s vice-president for news. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: And I’m Bob Garfield.