Alex Jones Doesn't Care About You

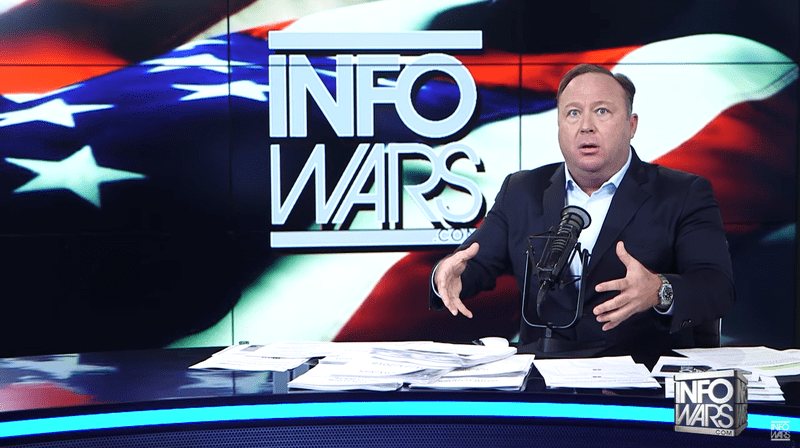

( InfoWars )

Micah Loewinger: Hey, this is OTM correspondent, Micah Loewinger. Our team this week has been glued to the January 6th select committee's hearings. On Monday, the focus was the big lie and the selling thereof. Historians tell us that the seeds of the January 6th insurrection were sewn well before the election. In fact, historian Richard Hofstadter coined his famous phrase, The Paranoid Style in American Politics, in the 1960s.

The fires have been fueled ever since by growing income inequality, immigration, a country confronting its past and building a different future, all those things and more, supercharged by a far-right media machine. The previous president just normalized fear and loathing while, as we've heard in this week's hearings, profiting mightily. While he may be the leading paranoia profiteer, he's certainly not the only one.

Owen Shroyer: It's my honor to introduce a man, who was the genesis, in many ways, of this second American revolution.

Micah: That's InfoWars host, Owen Shroyer, introducing Alex Jones at an event on the eve of January 6th.

Alex Jones: They are trying to steal this election in front of everyone. As I told them 20 years ago, I tell them again. I don't know how else this is going to end, but if they want to fight, they better believe they found one.

Micah: Alex Jones also helped plan and finance the Stop the Steal rally that preceded the insurrection, though he's yet to be charged. Despite the subpoena that put him face-to-face with federal investigators, the conspiracy theorist hasn't been particularly forthcoming.

Chris Hayes: In fact, Alex Jones sat down before the bipartisan House committee investigating January 6th, and oh, to be a fly on the wall. He pleaded the Fifth nearly 100 times instead of answering questions.

Drew Griffin: His own employees face criminal charges from an InfoWars editor who streamed the riot.

InfoWars Editor: It feels good to be in the Capitol, right?

Drew: To InfoWars host, Own Shroyer, who was right by Jones' side.

Owen: 1776. 1776.

Drew: At least 20 of those arrested either worked under Alex Jones appeared on his show or followed his content.

Micah: The scrutiny from federal prosecutors comes at an especially difficult time from the Austin-based host, who's in the midst of yet another high-profile case.

Female Newscaster: Families of those killed in the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in 2012 have now rejected a settlement offer from radio host Alex Jones. Jones offered to pay $120,000 per plaintiff to settle a lawsuit stemming from his claim. Jones has been found liable for damages and faces a trial to determine how much he should pay.

Micah: After begging his viewers to bail him out last month, the Southern Poverty Law Center discovered that Jones received $8 million worth of bitcoin from an anonymous supporter, demonstrating the power of a largely invisible network of donors and staff that have so far managed to keep the host on air. Josh Owens was one such InfoWars employee from 2013 to 2017. In an essay published on CNN.com this week, Owens described his deep regret over the past five years as he's grappled with the damage his work caused. Josh, welcome to the show.

Josh Owens: Thank you for having me.

Micah: You said you first started listening to Alex Jones in 2008 when you were 19. You wrote that you fell into "an alluring trap." Who were you at that age and what do you think you heard that spoke to you?

Josh: It's hard to say in retrospect, but I think that on some level, I was primed for Jones' world. I had never heard of Jones. It actually started, funny enough, with the film Dr. Strangelove. The friend was in town and we were watching that scene with Sterling Hayden and Peter Sellers. He's talking about water fluoride and my buddy paused it. He was like, "You know that's real, right?" I had no idea what he was talking about.

He jumps up, runs to the bathroom, grabs the tube of toothpaste, and he's like, "Look, swallow more than a pea-sized amount, but they put it in water?" Logically, I guess in my brain at that time, I was like, "Okay, I guess that makes sense." He told me to watch this documentary about this place called Bohemian Grove that I've never heard of before. I watched that documentary and it was Jones traipsing through the California redwoods, exposing this secretive group of powerful men.

It just hooked me. At the end of high school, I was directionless. I was raised in an evangelical household in the South. I was just questioning my beliefs and rebelling, I guess, against that upbringing, and there Jones was. It took me a while to see the irony of how similar he was to that upbringing. At first, it seemed diametrically opposed. It seemed like a completely different world that he was opening up. There seemed to be a lot of simple answers to a lot of complicated questions, so I was drawn in.

Micah: What was it about the fluoride documentary that felt liberating or that offered a different way of thinking from the way you'd been raised?

Josh: Well, first off, I think I lived my life through movies at the time. That was what I spent my time doing. Jones very much so, does a similar thing. He's almost living in a fantasy land and he attributes-- he uses the same-- he references movies a lot. The world is complicated. Politics, it's all complicated. Jones condensed it into this very simple version of-- It was binary. It was good and bad. There were bad people who wanted to do bad things and it was nefarious.

There were plots and conspiracies. I didn't have to think too hard. Not to say that people who believed in conspiracy theories aren't intelligent, but I think there's a difference between intelligence and education. I just don't think I had the tools at the time to discern what Jones was saying. The simplified version of the world he was portraying was appealing. I didn't see the negativity in it at the time.

Micah: Five years later, how did you go from just being a fan to actually joining his staff as a cameraman and editor?

Josh: I graduated high school. I had no intention of going to college. I was in a band and that was what my life was going to be. I decided to enroll in film school because, like I said, growing up, that was my language. That's how I saw the world. That's how I made sense of things and stories. Jones posted a reporter contest online. I was becoming a little disillusioned with film school. It wasn't really giving me the answers that I was looking for.

It wasn't as clear-cut as I thought it was going to be. I think I was foundering and I just thought, "Well, let me give this a shot." I went out to the Jekyll Island Club, where the idea of the Federal Reserve supposedly was thought up. I filed this report, submitted it, and I got in the top 10 of that contest. Through that, Jones offered me a job. I had no other prospects, so I decided to give it a shot.

Micah: When you started working with him, what did you glean about his philosophy and methods of filming, of telling stories, of conveying ideas? What was the secret sauce that you were taught?

Josh: I'm not sure if I was taught that much. I was thrown in the deep end. There is no training program there. You just copy what's been done before. The goal is just to meet Jones' expectations. It's up to you to figure out what those expectations are.

Micah: What were some memorable projects because he sent you out with reporters all over the country, right?

Josh: Maybe the second week I was there. Jones came in and he told me to get camera equipment together. We're going to interview Mike Judge, the filmmaker. I loved his movies and I was like, "Okay, great." I quit film school to go live a movie, I guess, and be around people like that. That was immediate. I think it was the second week. A couple of months after that, he started putting out his supplements. The first one was an iodine supplement called Survival Shield. I cut together the ad for that. He sent me and a couple of other guys out to Utah to the manufacturing facility, but his real goal sending us out there was to infiltrate the NSA Data Center. I just remember--

Micah: Did you know that when you went out there?

Josh: No, I didn't. No, I found that out once I got there.

Micah: What a ridiculous bait-and-switch.

Josh: Yes, I thought it was going to be a simple trip, and then it turned out-- I think Jones wanted us to get arrested.

Micah: Because if you got arrested, then it would seem like the government was targeting these intrepid InfoWars investigative reporters, and is that the idea?

Josh: Exactly, it's all performance.

Micah: Did you go to the NSA Data Center?

Josh: Yes, we did. We pulled into the parking lot. There are signs everywhere. "Do not film," "Turn around if you're not--" "No unauthorized vehicles." The cops came out. They were very angry. We live-streamed the whole thing to Jones' show and they wanted us to delete the footage. Long story short, I pulled out the card, pretended like I didn't know how to work the camera. I left with the footage and I was able to upload it.

I think from that experience, I earned Jones' trust. Before that, maybe he's a little skeptical. I'm just this guy from Georgia. He had no idea who I was, but I got what he wanted. That seemed to change things quite a bit. That's when he started sending me out on the road. Funny enough talking about Dr. Strangelove, six months after I started working for him, it was the 50th anniversary of JFK's assassination in Dallas.

Jones wanted everyone to go out there and he wanted to make it a big event. He got into a big altercation with the police and he was very aggressive, very confrontational. It turned out that Stanley Kubrick's daughter was in the audience, Vivian Kubrick. We had dinner with her that night. We sat with her and talked about her and she wrote music for Full Metal Jacket and was on the set of The Shining.

It was surreal. Jones had provided this world that I don't think I would've had access to otherwise. I think that was confusing because it felt like an opportunity instead of getting pulled into a world that was going to alter me personally. There was a lot of fear. Jones, that's his schtick, fear-based information. That's how he gets attention. In the office, it was very unhinged, very chaotic. Jones was a very manic person.

He would be laughing, joking around one second. The next second, he would be filled with rage and it was terrifying. There were two things happening, I think. I think a lot of my brain was just focused on moment to moment. It was, "Go do this trip. Let's file this report. This is a problem. This is great." There was so much going on that I don't think the forest for the trees. I wasn't able to step back to see what was really happening and what we were doing.

It also escalated. Not to jump forward too much, but when Trump announced he was running for president and then Jones got on board with Trump, which was something that I think it was a slow progression to that because I started in 2013 and I left in 2017, so I saw where Jones was on the fringe. Jones wasn't in the news really. Nobody was really covering Jones. Then when Trump came on his show, everything changed.

Micah: It seems like they helped each other.

Josh: Yes, why would Trump come on his show? I think he was trying to tap into a certain audience that Jones had. I was on the floor at the RNC when Trump said, "Americanism, not globalism, will be our credo." Jones was right next to me with tears running down his face.

Micah: You wrote, "Over time as I stood behind the camera and watched Jones ignore, conflate, misrepresent, and fabricate information, my critical thinking skills improved. Unfortunately, my education in media literacy came from learning how to circumvent it in others." What did you mean by that?

Josh: Well, I was standing behind a camera most of the time. I wasn't an on-air personality. I got to see, out on the road, Jones would say we had intel that this was going on. We had a source.

Micah: Could you give an example?

Josh: Yes, so it was the beginning of 2015. We went to El Paso and Jones claimed on the air that we had a source telling us that there was a terrorist training center over the border in Juarez. That wasn't true. That was just a complete lie. When you're there, you're on the ground and you're saying, "Well, we just got in El Paso. There's nothing to report." There was a judicial watch report that had been put out, but I think it was baseless. I don't think it was founded on anything credible. We ourselves didn't have any information and Jones was leading his listeners to believe that we did. There were a lot of examples like that.

Micah: Where he would use the language of broadcast journalism to sound credible, to sound like that reporting had been done?

Josh: Yes, it was almost like he was protecting sources and that was his excuse of saying, "Well, we have intel that this is going on," but we didn't and it wasn't true. That happened a lot.

Micah: Speaking of fabrications, you joined in 2013. That would've been shortly after the Sandy Hook massacre in which a gunman killed 20 children and 6 school staff in Newtown, Connecticut. What did you make of the Sandy Hook massacre, the story that Alex Jones told?

Josh: At the time, I wasn't fully aware of what Jones' story was. On some level, it feels like I'm making an excuse. I think that I am to a degree because I should have been. I should have had the discernment to see the damage that could cause the danger that that would cause. I didn't because Jones said that about everything. Everything was a false flag. Everything there was an ulterior motive. Everything was crisis actors. It didn't really happen. I'm just asking questions.

I think in retrospect now, when you can see the videos of Jones saying multiple times that it was a complete fabrication. It never happened. Then walking that back and then coming back around and saying it didn't happen again. It's all over the place. It wasn't until I heard some of those families speak out that I realized the impact of that, that there were people that were just maliciously going after them, them having to move multiple times, them not being able to go to the graveside of their children.

They suffered probably one of the most horrific things that a person can have to go through. Then on top of that, they had to deal with Jones' rhetoric leading to more things that they had to endure. It's almost worse that it didn't register to me because I didn't work on any reports of Sandy Hook. It wasn't really in my purview day to day. Like I said, it was like taking a fire hose straight into your mouth. It was just nonstop chaos, but that's no excuse. That's a guilt that I've had to carry with me that that didn't register.

Micah: Help me with the timeline a little bit. You started to hear what the parents were going through while you were still working there.

Josh: I really started to hear what the parents were going through after I left. It was the Megyn Kelly interview. There was a This American Life piece that I was somewhat involved with through the writer, Jon Ronson. When I started to hear the stories that those families were telling and the courage that they had to talk openly about what they were going through, that's when I feel like I really became aware of it.

Now, after Trump came on Jones' show, I know that when I worked there, there was a Hillary Clinton speech where she said something like Jones had a dark heart because he had used Sandy Hook as an opportunity basically to boost his own audience by pushing these conspiracy theories about it out. That was, I feel like, the first realization I had to like, "Oh, okay, well, this is real. I was also around the Pizzagate time."

It was Jones pushing these baseless conspiracy theories and people were taking action. Like that guy going to the Comet Ping Pong pizza place with a gun, it was learning about what these families had to endure, but that was after the fact. I can't say that that was the reason that I left or anything, but I definitely became acutely aware of the dangers and the repercussions of some of those ideas.

Micah: I'm wary of blaming too much on a single source. Even somebody who lies as prolifically as Alex Jones, some have credited him with helping Donald Trump win his election in 2016. In your opinion, what effect did he have on his viewers and on our politics at large?

Josh: It's hard to say because there are so many different types of people that listen to Jones. I think the majority of his audience, they get pieces of what he says. The word Jones would use all the time is a gestalt of his political theories. A lot of it would just align with their biases, their preconceptions, or prejudices. Jones almost gave people permission to believe the things that they already were inclined to believe.

Then there are people where they, like myself, are questioning things and Jones provides this simple explanation. It's horrific, the things that Jones says. It's not easy to hear, but it's an answer. For complex problems, sometimes it can be appealing. It can lead you down, what people call a rabbit hole. Then there are people who listen to Jones because they think he's almost like South Park. They think that Jones is funny.

As far as his effect on politics, it's hard to say. I think it's clear that Jones endorsing a political candidate, which is something that, on a scale like that, he hadn't really done before, especially a presidential candidate that had any chance of winning, which, at the time, I don't think many of us thought that Donald Trump had any chance of winning. I certainly didn't. That's not, I feel like, an answer that I can give because I haven't studied that, but-

Micah: Sure.

Josh: -I think the correlation is there.

Micah: In your New York Times magazine piece, you've said your coverage of Islamberg was a turning point for you. What was different about that particular assignment when you went to travel to this Muslim town in Upstate New York? Do you mind telling the story of that trip?

Josh: After this California trip that I've talked about publicly where we went to the West Coast, we drove all along the West Coast. Jones was looking for high radiation levels, send us out there with a Geiger counter. We did not find high radiation levels. He got very upset because we were reporting what we found. I think at that point, I started to realize that we weren't out there looking for the truth.

We were just out there to validate what Jones already believed, really didn't matter what we had found. After that, we started having meetings, where Jones could give us directives for what the goal was, what we were hoping to get out of a trip. Islamberg, Jones brought us in a room, and he was, "We're going to have this. We're going to send you guys to Muslim-majority communities."

The first stop was Islamberg. That was the main one. He wanted to call it an investigation into the American caliphate. There were some baseless claims circling the internet that this mostly African-American group of Muslims, who was just families living in a community, that they were somehow terrorists, that there was potentially a terrorist cell. Jones was like, "Go there and check it out. That's what we're looking for. That's what we're hoping to find."

Micah: How did you feel about the assignment?

Josh: I don't really know if I had a feeling about it at all. If I'm being completely honest with you, it was, "Oh, I have to go out on the road again? I have to be gone again. I have to be away from my partner and my dogs, and I really don't want to." I was very selfish. That's what my perspective was at the time. When we got there, we found none of the things that Jones said we were going to find. He said we were going to talk to people and they were going to say that they had heard gunshots.

Jones is a big Second Amendment guy, so gunshots anywhere else would be a sound of freedom to him. For some reason, if this Muslim community, if they were shooting guns, well, that was something to be suspicious of. We got there. There was nothing. We spoke to the sheriff. We spoke to the mayor of Deposit, New York, and all they had to say were positive things, that the people were kind, that they had interacted with them in their schools.

Their children went to school together, that they never had an issue. They never had suspicions. There was no reason to be concerned about anything. When we were there, I saw that Reuters had sent a team out to, I guess, "investigate" what was going on, so they spoke to some of the families and there was nothing. They found nothing, but that's not what Jones wanted. Jones didn't want us to report that there was nothing because that's not creating content. That's not what we're there to do. The reporter filed reports.

I filmed them and posted them online that were just blatant lies, that there was an Islamic training center, and that they were promoting Sharia law, which is a dog whistle. It was the intention of saying that was, "There's danger here." On the flight back, I was seated next to a Muslim woman and her young child. I can't explain it other than there was just something that kind of clicked in my head. It was like, "These are just human beings. These are just people and there are repercussions to what we're talking about."

Between that and being at the border and seeing that there are families that are having to deal with this stuff, going from the macro to the micro of seeing real human experience and just putting a face on it, I feel like I started to shift my perspective. I started to stop thinking about these big, grand ideas that Jones had been pushing for so long that were not about the people. It was about a political agenda.

Micah: After your New York Times piece came out in which you chronicled many of the things you've described to me here, there were all kinds of responses. People wrote pieces in response. The New York Times article had over a thousand comments. I did recently come across the response from some Muslim Americans, who had written about how they felt about what you wrote. They said that in a couple of cases that what you wrote was too little, too late, and that the damage in what you had participated in had already been done to these communities. I guess I want to know what you would say to some of these communities who feel your acknowledgment fell short.

Josh: I think that's a completely valid response and I understand it. I think it's fair to have that reaction because, on some level, it is too little, too late. Consciously, I just felt like it was my responsibility. I had been there, I had done these things, and I felt like that a lot of the responsibility fell on my shoulders too. I don't want to say, "Correct it," because I don't think you can. I think the damage has been done, but I do think that there is a culture of fear at InfoWars. A lot of people are afraid to talk about their experiences and a lot of people, when they leave, want to forget it. I was carrying a lot of guilt and I was carrying a lot of shame and it just felt like the right thing to do.

Micah: To speak up?

Josh: To talk about my experience and how that experience changed me because, look, I'm not an expert on Alex Jones. I'm not a social psychologist. I'm not someone that can look at these statistics and say, "Look, this is who listens to conspiracy theories." All I can do is talk about my experience. Someone asked me, "What led you to write that piece?" It was my conscience.

I felt bad about the things that I had done. I felt it was wrong. I had made mistakes and I wanted to, on some level, own those mistakes publicly. I wanted to have a platform to talk about my own complicity in that world because, sure, you can leave. You can walk away from it. I wasn't on camera much, so people didn't think of me connected to Jones. Like I said, I wasn't hired as a reporter.

Micah: I just noticed that the tone of the piece is full of sorrow and is regretful, but I noticed that you didn't use the words "apology" or "forgiveness." I guess I want to know if you feel like you have had the chance to apologize, if that was the point of the piece.

Josh: I don't know if it's fair of me to expect someone to give forgiveness. I don't think that I have the right to ask for that. I am wholly apologetic. I am incredibly sorry that I was a part of those things, that I didn't speak up when I was there, that it took me so long to work through my stuff afterwards to speak up. I didn't feel those things when I left. I was very angry when I left.

I wasn't angry at Jones. I was angry at myself. It was difficult to trust my own thoughts. It was difficult to work through, "Why had I done these things?" When I looked back at the person I had been, I didn't recognize that person. I had to do a lot of work to get to that place where I could understand it. I certainly didn't want it to come off as if I was some acrimonious employee who was looking for revenge. I chose to quit. Jones begged me to stay. I left that job because I had done things that I was ashamed of.

I was trying to be a better person. I will say this now and I've said it before, but I'm incredibly sorry for the things that I had done and I take full responsibility. I'm also not here to say that Jones is responsible for the things that I did because, ultimately, that responsibility falls on me. I don't think that it's fair of me or right of me to sit and ask for someone's forgiveness because those people, there's no expectation that anyone will give me forgiveness.

Micah: In 2018, Alex Jones saw his podcast and social media accounts kicked off of Spotify, Facebook, YouTube, Apple. I think that was the moment that a lot of people who are listening to this stopped thinking about him, but you don't think that deplatforming him hurt his show and his cult of personality quite as much as it seemed then.

Josh: Well, look, Jones has spent 20-plus years cultivating this audience. I do think it hurt him in that it's more difficult for him to reach new people. I don't want to say that it hasn't affected him. I just think that Jones has this knack for-- I don't want to be trite, but Jones is like a cockroach. I don't think he's ever going to go away. I don't know if he sees some of the repercussions he's facing as repercussions or just unfair attacks from what he sees as "the enemy." Jones was publicly diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder.

Micah: This was from doctors who hadn't seen him personally as a patient, is that correct, or was this something that came out of one of the lawsuits?

Josh: I believe it was in his custody trial.

Micah: Okay, that's right.

Josh: It's futile to try and understand why Jones does what he does and who Jones is really. I'm not going to sit here and claim to know Jones and know why he does the things that he does. I do think that on some level, it seems, at least this is how it seems to me, being around him for four years, that there is an inability to take ownership of his own mistakes. There is an inability to show remorse, it seems. He doesn't seem to take responsibility for his hand in a lot of the things that he's having to answer for now.

Micah: Do you remember where you were when you learned that there was an insurrection happening on January 6th? Did you think of Alex Jones on that day?

Josh: I thought of him on that day because he was there. Yes, of course, I thought of that because it was all kind of baked into Jones' ideology. Jones was having people chant 1776, I believe, the night before. Yes, I don't think with my experience being in that world, I could have looked at January 6 and not seen Jones. Also, separately, he was there.

Micah: [laughs] I'm curious what you think January 6 meant, and to what extent did it align with what Alex Jones had espoused?

Josh: What it meant was that a culmination of things where that's the worst it's going to be, or is that the beginning of something? Did that open up this space for this new ideology to spread to different types of people? I don't even want to speculate because I don't think I'm the person to answer that question.

Micah: As the January 6 committee continues to reveal its findings, at least for me, it's hard not to feel a bit pessimistic. You have that feeling watching it that the people who need to be watching it aren't or are getting some sanitized spun version from Fox or other right-wing media outlets. Reading your recent CNN piece, it seems like you really do believe that reaching across the divide is not only important but is possible.

Josh: I have to believe that it's possible because, on some level, it worked for me. Not everyone can go spend four years working for Jones, and I certainly don't want them to. Yes, I have to believe that there is hope in having conversations and people talking to each other. Maybe that's being idealistic to say that simply having conversations can change people's minds because I think, in some cases, that's just not true, but what else do we have? Deplatforming people like Jones is a start, but I think there is false comfort found in that deplatforming because those messages still spread. Those people are still out there. They're still saying the same things. Are more people listening? I don't know. It seems like maybe. Maybe they are. I don't know.

Micah: Based on what you've learned what worked for you, what would you say to somebody who is deeply convinced of the big lie or entrenched in any number of this constellation of beliefs in conspiracy theories?

Josh: Well, I think it all comes down to people. I think if we stop taking these politically-motivated ideas and we just look at, how does overturning Roe v Wade affect real people? What are the real effects that that has on people? You see that at the border. I saw it in Islamberg. I saw this hate-filled rhetoric have a real-world impact on individuals.

Micah: We've been talking for a while. I guess I'm just trying to figure out, where do you think this conversation ends?

Josh: Let me ask you this. What was your point in having me on?

Micah: That's a great question. Well, we have been talking about the hearings, 2000 Mules, which is a film that received a nationwide in-theater release that has presented some very dubious and debunked claims about how the election was allegedly stolen, which it was not. We're coming to you, somebody who worked to help furnish the machine that amplifies and creates disinformation and harmful conspiracy theories, someone who's come out the other side. What you might have learned about why the Alex Joneses of the world are as effective as they are, and what can be done to help the people who are being hurt by him?

Josh: Well, I don't think there's a one-size-fits-all. I think everyone's circumstances are different, but what I can sit here and say is that I was part of that machine. I was part of putting out various mis and disinformation. We lied. We did not represent circumstances accurately. It was intentional. Alex Jones doesn't care about the people that he speaks to on a regular basis. I don't know if a lot of those people are looking for that community that I was looking for. They're looking for that validation, but all I can say is I can promise you, you aren't going to find it there.

Micah: Josh, thank you very much.

Josh: Thank you very much.

Micah: Josh Owens wrote about his experience working for InfoWars for CNN.com in an article titled I escaped Alex Jones' world. This is what I learned. Thanks for listening to this week's podcast extra. On the big show this week, Brooke and I are exploring the disinformation business. See you then. I'm Micah Loewinger.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record