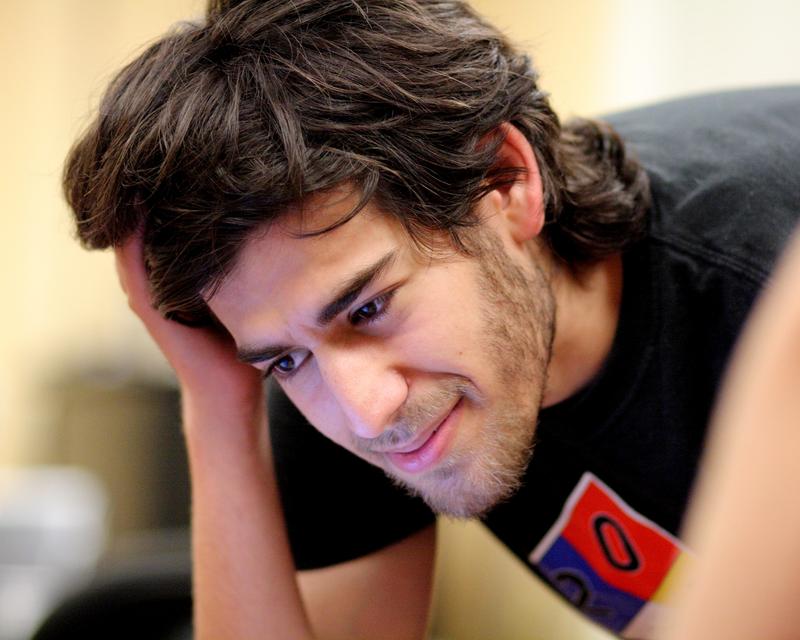

Aaron Swartz: The Wunderkind of the Free Culture Movement

( Sage Ross/flickr )

Brooke Gladstone: This is on the Media's midweek Podcast. I'm Brooke Gladstone. January 11th, will mark the 9th anniversary of the death of Aaron Swartz. The 26 year old software developer and political activist killed himself in his Brooklyn Apartment. He'd been indicted on federal charges after illegally downloading 4.8 million articles from JSTOR, a database of academic journals, and he potentially faced a million dollar fine and decades in jail. These are the basics of the Swartz story, facts that made headlines and introduced much of the world to a computer programming prodigy, a fierce advocate for the free exchange of information, a long time internet folk hero. Here's Swartz in a 2011 interview.

Aaron Swartz: I slowly had this process of realizing that all the things around me that people had told me were just the natural way the were, the way things always would be. They weren't natural at all. They were things that could be changed, and they were things that more importantly, were wrong and should change. Once I realized that, there was really no going back.

Justin Peters: That is a pretty accurate distillation of the way he seemed to have lived his life.

Brooke: I spoke to author Justin Peters in 2016, after he'd written his book, The Idealist: Aaron Swartz and the Rise of Free Culture on the Internet. The book recount Swartz's prolific, but often troubled life and his tragic death, but it's much more than a biography. Peters places Swartz on the long fraught history of copyright in America alongside other so-called data moralists with whom Swartz shared key qualities and an unshakable commitment to the idea memorably sloganized by Whole Earth Catalog founder Stewart Brand. That information wants to be free.

Justin: Information wants to be free is only half of it. The full statement was information wants to be free because it has becomes so cheap to distribute, copy and recombine, too cheap to meter. It wants to be expensive because it can be immeasurably valuable to the recipient, and that tension will not go away, because each round of new devices makes the tension worse, not better. The thing that I found so fascinating when I started researching it is that this is not a new problem. This paradox that Brand described in the early 1980s, goes back all the way to the 18th century.

Brooke: In fact, you launched the book with Noah Webster, famous for his Dictionary, but apparently kind of an insufferable prick.

Justin: That is about describes it. He's a very difficult dude, alternately insecure and very strident, very upsettable and upsetting to people.

Brooke: He's in your book because he's essentially the founding father of copyright in the US.

Justin: He was perhaps the first American to actually try to make the case to the broader public that authors should have the ability to control their own work so that they can profit from it, and make sure that it is being distributed and reproduced in the way that they want.

Brooke: What was he trying to copyright?

Justin: It was a speller, a grammar book that you would use for schoolchildren to teach them how to read and write and speak. It's super interesting because the revolutionary was over, and now it becomes a much more extended battle for America's cultural independence. The primary text to that children were using to learn to read and write was this book called of A new guide to the English tongue. This is a very dull book by a deceased British schoolmaster named Thomas Dilworth. Webster eventually came to think, "Why is it that we are using this book that glorifies British customs and devotes dozens of pages to proper pronunciation of the names of Welsh towns, when we literally just expelled these dudes." Webster started writing his own speller that he thought would help bring the nation together and create a distinctly American language.

Brooke: It was a wild success.

Justin: It was a wild success. It was published in the mid-1780s, and by 1800, it was selling about 200,000 copies a year, which made it by far the most popular American book that had ever been written.

Brooke: We didn't have a literature.

Justin: No. It was also one of the only American books that had ever been written. There was no American literature. For about the first hundred years of American history, authorship was a hobby. It was something that rich men did, rich women did.

Brooke: Come on, how many rich women?

Justin: There was at least three. At least three rich women. The whole notion of copyright was Webster and some other authors saying, "Look, in order for there to be a sustainable literary middle class in America, for the situation to be such that author can write their own books and profit from their sale and not have to worry about obtaining the patronage of wealthy people in America or doing this in odd hours, then we need a copyright. We need it to last long enough that authors of books can actually find some sustainable profit from the things that they write."

Brooke: In order to push this law through Congress, you note this trail that he makes across the country assembling letters of recommendation from famous people, not least of whom was George Washington.

Justin: He showed up at Mount Vernon completely unannounced. That in a itself was not particularly weird. It was a thing that Americans did in that postwar pre-presidency era to just show up and shake George Washington's hand. Washington invited him over for dinner and started talking about, "Well, I want to hire a secretary who can be a schoolmaster to my wife's grandchildren. I'm thinking of hiring a gentleman from Scotland." Webster just got super offended.

Now, picture this, it's George Washington's dinner table, and Noah Webster, this 27-year-old writer of a book that no one had actually read yet, a school teacher stands up and starts lecturing George Washington about the nature of patriotism. He says something like, "What do you think, sir, that the British would think if they found that after we had obtained our independence, we had to send away to Scotland for appropriate instructor? What rubbish. There are plenty of men trained in Northern in colleges who could suit your purpose." Noah Webster was a prolific diarist and he closed off this story by saying, and then there was silence at table.

Brooke: [laughs] Eventually, he does collect a very tepid letter of recommendation.

Justin: Washington reads something like, "I cannot speak to the book's merits. The book will have to speak for itself. Goodbye." That was enough. All that he needed were George Washington's name and the names of all these other famous people whose doorsteps he had darkened. One by one, he went to America's various state legislatures and he gradually persuaded them all to pass their own individual state copyright laws.

Then in 1790, the first federal Copyright Act came about. It allowed for a 14-year initial copyright term, and the copyright could be renewed for 14 more years. Then the work fell into the public domain, which meant that you or I or anyone was free to reprint it, distribute it. The term was limited because Congress was trying to strike a balance. They said, "Okay, yes, it will be good for America to germinate a literary class here. It is also good for America to allow knowledge to spread unfettered."

Brooke: The copyright act that Webster helped get through also means that American books become expensive, but because there's no international copyright, foreign books which America has always ripped off, aren't very cheap, and they sell by the ton.

Justin: There had been effectively a century in American history in which overseas books could be bootlegged and distributed for free in the United States. Publisher did not have to pay a dime. That was basically how the American publishing industry was built, on the backs of these overseas authors who had no legal right to any compensation. Charles Dickens came to America in 1841 and spent the bulk of his lecture tour repeatedly be rating his hosts for their bad manners in taking his books and pirating them and not giving him a dime. The Americans just basically shrug their shoulders saying, "Thanks for coming."

[laughter]

Justin: Then they went on doing it. American writers hated the lack of international copyright, because why would anyone publish a homegrown book and take a chance on a new author, when they could take a book that had already been established, overseas and sell that for free? The American publishers and some American authors got together and said, "We need to change this." For a period of about 10 years preceding 1891, they embarked on this extended lobbying campaign in which they attempted to make the case that it was morally wrong to purchase cheap books, and that it was morally right to allow authors to benefit from the sale of the fruits of their labor.

Brooke: Where would be the best place to present a moral argument?

Justin: In church. This is literally one of those things that they did. They would convince preachers across the country to work pro-international copyright messages into their Sunday sermons. They're really ludicrously excessive. This one minister Henry Van Dyke, I think he was something like "My neighbor might love the light, but that gives him no right to steal my candles." It's just stuff like that. Future copyright campaigns would do the same thing. They're like, "Look, we need to establish that stealing other people's literary property is wrong."

Brooke: You make the point that in every era, every new piece of legislation renders copyright more and more stringent, more in favor of the keepers of the knowledge than the public interest. Before we get to Aaron Swartz, and we are getting their listeners, tell me about what happened to the idea of the public domain?

Justin: The goalposts shifted as members of the public got excluded from the conversations around new copyright legislation. The interests of authors and the interests of the public gradually began to conflate until the framers of the new copyright acts were all basically in accord that what was good for authors and publishers, was good for the public. They started saying, "Look what is the good of having the public domain?" That just means that nobody cares about it. It's like the equivalent of a weedy vacant lot. Whereas where the public really benefits is in having these strong, robust copyright terms that encourage creators to create more books in music, in film. That became the argument because there were very few people around to take the opposing viewpoint.

[music]

Brooke: We'll hear more from Justin Peters after the break when he tracks the rise of the Free-Culture Movement and the loss of its Wunderkind. When we left off with Justin Peters, Noah Webster's copyright campaign had paved the way for laws that would protect the creators of information, literature, music, film with robust copyright terms. The idea that the nation needed a public domain rich with free and freely available information was receding, but the advent of the internet created an opportunity for some fervent free culture advocates to step in. In the late '70s, for instance, we encounter Michael Hart, Swartz's spiritual progenitor. Peters suggests that people like Swartz like Hart, people passionate about information, share certain traits.

Justin: Absolutely. I think these data moralists, to use a term that I may or may not have coined, they live these lives free from ambiguity of the rightness of their causes, how either expanding or restricting access to information is not just good for readers and writers but for the country as a whole. Michael Hart is definitely in that line. He's a critical bridge figure between the old guard publishing world and the burgeoning world of the internet.

Brooke: You call him the beginning of the story of the Free-Culture Movement.

Justin: Michael Hart created the first eBook. It was on July 4th, 1971. He was doing a sleepover in this computer lab at the The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and he had this flash of inspiration that people have. I've never had one, but one of these days. He had this flash of inspiration. He announces to the people sitting beside him sidebar Michael Hart seems to have spent a good portion of his life announcing things to people who might not have cared to hear it. He announced that the greatest value created by computers would not be computing, but the storage, retrieval and searching of what was stored in our libraries.

Brooke: Think about when he said that. This was when computers were still for crunching numbers.

Justin: They were basically all used for mathematical and scientific purposes, and here's this guy. This guy who had dropped out of college twice, who had been in the army, had left early, had spent year hitchhiking across the country and trying to make it as a folk singer, who finally has this flash of inspiration when he's in his early 20s, that he's like, "This is what I'm going to do with the rest of my life. I'm going to devote my life to typing up public domain texts and storing them in computers for the benefit of humanity." That's exactly what he did.

Brooke: He created what may be familiar to many listeners, something called Project Gutenberg.

Justin: Project Gutenberg was the first general interest online library. He spent the first 20 years of his project toiling in obscurity, bouncing from job to job during the day. He spent the entire 1980s transcribing the King James Bible. It's a very long book.

Brooke: He was basically camping out at a university computer.

Justin: Exactly.

Brooke: They just let him basically couch surf.

Justin: Because no one else really knew what they were for. Then the worldwide web comes along and people start discovering this project, and then start typing up public domain text that they find and sending them to Hart and gradually this becomes an actual online library. In the 1990s when the commercial potential of the worldwide web finally becomes apparent to people, Michael Hart had put 250 eTexts online, which might not sound like a lot, but if you think about the amount of labor required to sit and literally transcribe an entire book on early software programs, then you get some sense of the hugeness of this accomplishment.

Brooke: He gets kicked off that computer.

Justin: Yes. By that point right around the 20th anniversary of Project Gutenberg, the University of Illinois and indeed the rest of the world is starting to learn what computers are for and what they're not for. They're beginning to realize they're not for people like Hart. They revoke his access, and the project maintains. He finds a new home for it, but the fact that this happened right when by all rights the world should be looking at this great, beautiful thing and saying, "More please. How can we help?" Just illuminates the initial dichotomy that we were discussing earlier of information wants to be free, information wants to be expensive, and there's this endless tension between the two.

Brooke: Aaron Swartz. Swartz is growing up a precocious kid in the suburbs of Chicago at which time he creates a precursor to Wikipedia, and then at 14 he helps develop RSS, which helps people syndicate information online. Then he meets Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig when he's 15, and he gets himself involved with Lessig's effort to create a way to provide information for free under certain circumstances.

Justin: It was a project called Creative Commons, an attempt to create a middle ground for copyright in the digital era, where you could go on to Creative Commons and register your content with a Creative Commons a license which was basically just a sign post you'd put up to say, "If you are using this for example for nonprofit purposes, just give me credit." Or you could say, "Anybody can use this photograph or this song or this short story." It was basically an attempt to say, "Our copyright law at this point needs to adapt to the realities of the digital age, but if it's not going to adapt on its own then we'll find a workaround."

Brooke: As we follow Swartz, he drops out of high school. He then applies to Stanford, gets in, drops out of there. He's involved with the founding of Reddit, and somewhere along the line you write about Swartz reading Noam Chomsky's book Understanding Power.

Justin: On his blog he wrote that after he read Understanding Power, he was literally struck down to the floor. I think he said something like, "I couldn't stand up. I couldn't think straight. I had to grasp the doorknob to keep myself upright." Anyway after reading that book something seems to have switched, and he seems to have realized, "Now that I've seen this, I can't unsee it. Now that I've seen how power works and accumulates, I can't pretend that I don't know how the web works."

Brooke: We're still talking about a kid here.

Justin: He was 14 or 15 when he started working with Creative Commons. By the time he's writing about Noam Chomsky, he's barely 20 years old, going across the country speaking to groups about the moral necessity of liberating pieces of culture and information that are held as literary property.

Brooke: In fact, he embraces revolution.

Justin: Of a kind, yes.

Brooke: He drafts the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto. He starts the content liberation front. These are phrases at least designed to evoke revolution. I have a quote here from the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto. "It's time to come into the light and in the grand tradition of civil disobedience, declare our opposition to this private theft of public culture. We need to take information wherever it is stored, make our copies and share them with the world. We need to buy secret databases and put them on the web. We need to download scientific journals and upload them to file sharing network. We need to fight for Guerilla Open Access. With enough of us around the world we will not just send a strong message opposing the privatization of knowledge. We'll make it a thing of the past. Will you join us?"

Justin: Then two and a half years later, he's arrested at MIT after having downloaded 4.8 million academic journal articles. He never admitted or said what he was planning to do with all of the material he had acquired. The federal government certainly took the Guerilla Open Access Manifesto to heart, and they said, "He wrote about taking these gigantic datasets and freeing them to the world, then he downloaded all of this material." It was clear to them at least what they thought that he wanted to do with it.

Brooke: Tell me how the case unfurled?

Justin: It's the beginning of January 2011 when he's first arrested, and at first they bring him up on state breaking and entering charges.

Brooke: Because he did it from MIT.

Justin: He did it from MIT where he was not enrolled and he wasn't employed there. Then federal prosecutors get involved, this joint computer crime task force that was working the case with MIT cops, Cambridge cops, and the Secret Service.

Brooke: Basically, JSTOR, this repository of academic journals that you have to subscribe to, probably wouldn't have cared, except that he was doing it on such a massive scale that it slowed down and crashed their servers initially.

Justin: Yes, he was making hundreds of download requests per second. That was a big strain on the JSTOR servers. The JSTOR staff looks at this activity and thinks, "Whoa, someone is trying to siphon our entire archives." They start telling MIT, "Hey, you got to find the guy who did this." When they found him, and they found out that it was Aaron, not some malicious hacker, but a guy who had in many ways established himself as, if not the conscience of the internet, at least one of them, no one really knew what to do with him.

Brooke: Except the prosecutor.

Justin: Oh, they knew exactly what to do with him. They wanted to put him in jail, and they would not budge from that stance. They charged Aaron under something called the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, the CFAA, which is America's omnibus computer crimes legislation that serves to prosecute malicious hackers who are trying to tap into government computers to find state secrets. It can also be used to prosecute you or I, if we violate a website's terms of service. It's an incredibly broad piece of legislation.

Swartz returned all the documents he had taken. He gave them back to JSTOR, and then JSTOR called the prosecutors and said, "We've gotten what we wanted. We have no interest in seeing him go to jail. We have no interest in seeing this case proceed." The prosecutors said, "Thank you very much. Duly noted." Then they delivered an indictment that could have theoretically landed him 35 years in a federal prison. Then they delivered a superseding indictment that upped that to a potential 90 years. He never would have received the maximum sentence. That was just there for scare value, but still, the lead prosecutor in the case made clear that if they went to trial, and if Swartz lost, that the prosecutor would ask that he be sentenced to around seven years in federal prison.

Brooke: The boy and the man you describe, Aaron Swartz, couldn't handle any confinement. He couldn't make it through high school. He couldn't make it through college. He couldn't even work at a cozy comfy job at Reddit.

Justin: He was a very sensitive kid who couldn't stand having to play by someone else's rules. By which I mean he was a product of the internet, where this collaborative digital world in which you advanced by the strength of your own ideas and your contributions to the group. If there was a better way of doing something, a better way of solving a problem, then everyone said, "Great, you've found a new way. Let's do that." That dynamic just is very hard to find in the real world. You can't go to high school and say, "All right, we've got this four-year structure here. I've got this better way that is better suited for me." He tried to do that. They said, "Duly noted?" No. He left. He was in the first class of Y Combinator startups. Y Combinator is the big startup incubator that's relatively famous. He couldn't take that. He did not like being forced to work on one thing. That was not his thing.

Brooke: If it didn't have the potential to change the world, he lost interest. One of his friends said that he always felt like they were disappointing Aaron that they couldn't live up to his standards.

Justin: Well, he was the sort of person who was a great friend but could be a difficult collaborator because his mind was working on a different frequency than everyone else. I think that was partially why he ended up starting so many projects and then leaving them because they couldn't live up to his own standards.

Brooke: How did he die?

Justin: It was January 2013. It was becoming more and more clear that this case wasn't going to go away. He got new lawyers. They were very good lawyers, and they were going to try to convince a judge to exclude a bunch of evidence that the government was planning to use. That's the thing that kills me, that I just don't understand after living with the story for so long, it felt like things were looking up for him after living under the strain of an extended indictment for two years at that point. The case was looking like it might resolve in his favor.

He had a girlfriend whom he loved, and their relationship had never been stronger, and everything seemed to be going so well. Then one day his girlfriend comes home from work to find him hanging by his own belt, and the entire world sat up and asked why.

Brooke: There have been basically two competing narratives about Aaron Swartz since he died. One is that he was a restless, frustrated young man, a high school college dropout, a social misfit, a difficult colleague. Then there's the narrative that asserts he was smarter than all of us, possessed with more commitment and integrity, and generally just too good for this world. Actually, those narratives don't preclude each other. Both could be true.

Justin: He's an idealist. Someone who has a very clear idea about how the world should be and about what he can do to bring the world to that point, and yet he was ill equipped to deal with how the world actually was.

Brooke: Did your opinion of him change as you reported the story?

Justin: It did. Honestly, at first, I came at this story on the side of stringent copyright. I'm a journalist. I've seen a lot of my friends lose their jobs in this last decade because no one's paying for content anymore. The more I learned about this story, the more I'm like, "This is an extraordinary guy." You know what he was? He was a herald. This is near the end of my book where I try to sum it all up. It says, "Three years on, the story of his life and death serves as a necessary reminder that there is a fundamental disconnect between our laws and our habits, between the way we are supposed to conduct ourselves online the way we actually do. We can amend the bad laws. We can promote better culture. We can choose to create systems that can be opened without breaking, that tolerate deviance without it collapsing. That regard the unfamiliar not as a threat but as an opportunity."

Who Aaron Swartz is to me, he's the living manifestation of those ideas. Those ideas are supremely important today, tomorrow, in the future. As information continues this paradoxical need to be free and expensive you know what it ends up as? It's up to us.

[music]

Brooke: Justin, thank you very much.

Justin: It's such a pleasure, Brooke.

Brooke: Justin Peters is author of the book, The Idealist: Aaron Swartz and the Rise of Free Culture on the Internet.

[music]

Brooke: Hey, thanks for checking out our midweek podcast. Remember, the big show is posted on Friday around suppertime.

[music]

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.