The Privacy Show

Brooke: From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. Coming up this hour: surveillance and privacy. How do you balance convenience, security, and the discomforting feeling... no, certainty... that you're being watched?

Daniel: If people are asked to give up their privacy, they better get more security in return.

Hasan Elahi: And then I basically turned my phone into something similar to an ankle bracelet, so everyone... including the FBI... would know where I was at any given moment.

Eva: The wishful thinking is that if you do this fairly simple thing you will not have to do the hard work of protecting your privacy or protecting your data.

Jacob Appelbaum: Does it matter if Google knows that you're gay? I don't know. Do they have any homophobic engineers with access to that database?

Ryan: The internet is a giant copy machine. Anything you put on the internet can be copied and sent around. I just hope you have nice friends.

Brooke: An hour on privacy, or the lack thereof, coming up.

Bob: From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Bob Garfield.

Brooke: And I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Brooke: At no point in history have civilians been more vulnerable to government surveillance or prying by private companies. And what a curious trio of factors have brought us here: fear of terrorism on the one hand, the profit motive on the other, and on both hands the fun and convenience of life online. Whether for utility or security, loss of privacy is a trade off, sometimes conscious and sometimes not, and perhaps the defining bargain of our times.

Bob: But is it a bargain as in a good deal or a bargain as in Faustian? We're devoting this hour to considering the issues of privacy and surveillance. We'll review some of the latest refinements in snooping online, on the phone, and even on the road. But we'll begin by examining our own illusions.

Bob: In the next report, OTM producer Sarah Abdurrahman may be telling the savvier among us what we already know, but most of us still cling to the notion that we... with a few simple precautions... can handle our own security when we venture online.

Speaker: In response to the new Facebook guidelines, I hereby declare that my copyright is attached to all of my personal details, illustrations, graphics, comics, paintings, photos, and videos. Anyone can copy this text and paste it on their Facebook wall. This will place them under the protection of copyright laws.

Sarah Abdurrahman: If you're on Facebook, chances are that you've recently seen that statement on the walls of your Facebook friends. You might've even copied and posted it yourself. It went viral. But as the Electronic Frontier Foundation's Eva Galperin observes, it was all a hoax.

Eva Galperin: This sort of wishful thinking that powers this hoax is if you do this fairly simply thing you will not have to do the hard work of protecting your privacy or protecting your data. Often it stems from a misunderstanding about how the internet works or how privacy works.

Sarah Abdurrahman: A lot of behavior springs from that misunderstanding. We take some measures to protect our data, but they're often the wrong measures. It's like ordering a Big Mac, large fries, and a diet Coke. The intentions might be good, but we won't get the results we're looking for. Same with that viral Facebook meme. Within hours, countless people wasted time posting it to their walls, but according to Sarah Fineberg director of policy communications at Facebook, when they actually offered their users a real chance to vote on how the site is governed...

Very few users were engaged in the vote. Far less than one percent of users. My sense is that many more people were focused on the copyright meme.

Alessandro Acquisiti: Our privacy attitudes and our behavior are much less rational and stable than what we may like to believe.

Sarah Abdurrahman: Alessandro Acquisti co-directs the Center for Behavioral Decision Research at Carnegie Mellon University. He says the more you believe yourself to be in control, the more likely you are to act. The people who posted that bogus copyright notice on their Facebook wall felt like they were in control.

Alessandro Acquisti: On the other hand, in the Facebook election, I can express my preferences but really I have no guarantee that these preferences will be satisfied.

Sarah Abdurrahman: Of course, it's not just Facebook. Any time you use a service from what's known as a third party provider you are subject to its terms, and that usually means it owns your data and do what it wants with it.

Eva Galperin: If you're using Gmail, your mail essentially belongs to Google, and Google can decide what they want to do with it. Google has a terms of service and a privacy policy that says they will not give it up, but they're not required to do so.

Sarah Abdurrahman: Galfren says people don't really grasp the lowly legal status of their emails.

Eva Galperin: And they don't have the same 4th Amendment protections that they would if the mail was sitting in their house. Governments and law enforcement agencies... even people involved in civil cases... could possibly come to the webmail provider and get that information with a warrant.

Sarah Abdurrahman: In fact, even without a warrant if your email is older than six months.

Sarah Abdurrahman: Ryan Singel, former editor of wired.com's Threat Level Blog, says that's a by-product of an outdated law.

Ryan Singel: When they originally set up electronic privacy law in the 1980s, everybody always downloaded their email. You didn't leave it on the server. Anything over six months was considered abandoned, whereas these days you leave stuff up on the internet forever in your accounts.

Sarah Abdurrahman: But what if you don't actually send your electronic correspondence? Remember that affair between David Petraeus and Paula Broadwell? The couple reportedly used a tactic favored by terrorist and teenagers to keep their communications secret. They left their messages as drafts in a shared email account.

Ryan Singel: The idea is that if you write a draft to someone and you leave it there the email never gets sent to that person, so there's one less hop, which means one less place for somebody to see something.

Sarah Abdurrahman: But Petraeus and his mistress were found out, so a perfect plan it is not. And if the director of the CIA can't cover his tracks online what hope is there for the rest of us?

Ryan Singel: People often think if throw something in the trash and delete that it's therefore off of their computer. That is not the case. People that if they erase their browser history that nobody is going to be able to figure out where they went online. It does make it a lot harder, but it's not impossible to get. Skype is one. People think things are encrypted. It is encrypted, but most of the time Skype saves chats on your computer. People make mistakes about using open wifi or neighbor's wifi to do things that aren't legal. The other one I love is that businesses put those little disclaimers down at the bottom of their email: "This email is only for the intended recipient and you can't forward it on." That has absolutely no meaning whatsoever.

Sarah Abdurrahman: So why do people do it?

Ryan Singel: Because it can't hurt to add it and it might scare people. But every lawyer I talk to has said, "No, that's not true." If you get an email that's not intended for you and it's got some crazy secret, send it on to the New York Times. You're not going to get prosecuted.

If you want to say something to someone that's very personal, pick up the phone and call them or say it in person. The internet is a giant copy machine. Anything you put on the internet can be copied and sent around. I just hope you have nice friends.

Sarah Abdurrahman: The reality is that once you release an email into world or post a Facebook status or even send an off-the-record chat, you have no control over what happens to it on the other end. Even though many companies that you store private information with online promise not to disclose any of it...

Jacob Appelbaum: Those promises are no good when the rule of law comes into play.

Sarah Abdurrahman: Computer security researcher Jacob Appelbaum says even the most well-intentioned company has to comply with the law.

Jacob Appelbaum: That's happened to me with my Gmail account. The US government took my Gmail with less probable cause than a search warrant would've required by far. That is an example where privacy by policy is an utter failure.

Sarah Abdurrahman: He says the only way to keep companies from divulging your personal information is to encrypt it... all of it... so they can't collect it in the first place.

Jacob Appelbaum: The trick is to change it from a dynamic where you basically say, "Please promise not to take this data. Please promise not to exploit me," but they do anyway... or they've been compromised so they don't know they're doing it... and take it to a place where they can log it all they want, but whatever they log is worthless because it's encrypted.

Sarah Abdurrahman: So now it's on you. What a pain. You might think, "Who cares if my information isn't private? I've got nothing to hide."

Jacob Appelbaum: Does it matter if Google knows that you're gay? I don't know. Do they have any homophobic engineers with access to that database? For example, in Uganda right now they're trying to pass what people call the kill-the-gays bill and that's a great example where today the information about you, which can be found by your social network, is a life or death issue.

Sarah Abdurrahman: Your online life can be targeted for any number of unexpected reasons. Just ask Wired Magazine writer Mat Honan, who recently had his whole life digital life destroyed by hackers. They wanted something he had.

Mat Honan: They had gone after me because they saw that I had a three character Twitter handle, which was valuable real estate. Everything they did was all collateral damage to get that Twitter account.

Sarah Abdurrahman: Collateral damage including wiping away years of messages, documents, and every photo he had ever taken of his 18 month old daughter. Honen's sobering experience taught him that the one thing we all use every day to shield ourselves online... the thing that makes us feel protected and in control... the password, is actually a dangerous illusion.

Mat Honan: The password is just a string of data and there are all kinds of ways to either get around it or get it and copy it.

Sarah Abdurrahman: Honen says a password is especially vulnerable because it is a singular point of entry that can be attacked from multiple fronts: through malware on your devices, large password dumps online, phishing, brute force, or the strategy used to get into Honen's stuff, password resets. A person trying to get into your online accounts can often reset your password using information already available online.

Mat Honan: If I call up tech support and I happen to know your mother maiden's name, which I've gotten from Ancestry, or your high school mascot, which I've gotten from classmates, or date of birth that I've gotten from Facebook, I'm most of the way there to getting a password reset.

Sarah Abdurrahman: And you know that password trick we're always told to use, replacing letters with other symbols?

Mat Honan: A five for an S, a dollar sign for an S, a four for an A... If you can think of it, there's a computer program that can do it.

Sarah Abdurrahman: And go ahead, keep trying to make your passwords longer and more complicated. There are computer programs that can figure those out, too.

Mat Honan: It's an arms race between how many characters you're willing to enter in and how good our computers... and the programs we run on them... are going to get.

Sarah Abdurrahman: We all know we're not supposed to reuse passwords in multiple places, but repeating password patterns is no good either.

Mat Honan: Some people will do this thing where they'll have a password that can be, say, 123google, and they'll think, "Okay, that's my Google password. My Facebook password is 123facebook, so it's totally different," but it's not. People reuse passwords because they don't know how else to remember a good password. This has been the longtime problem with security. People won't take steps to secure their information unless it's convenient.

Sarah Abdurrahman: It's precisely that trade off of convenience over security that keeps people online.

Mat Honan: We can walk down the street and ask Google what's the best place for sushi within three blocks. Facebook has been really great at keeping people connected. If you want to have a party and you want to invite people, or share photos with all of your friends, that's pretty cool. So it's hard when you balance the things that you get with it with the things that you don't want. Like, you don't know, if you put that picture up, who's going to see it. How do you keep a stalker from coming after you? How do you keep an ex-boyfriend from keeping tabs on you on Twitter.

Speaker: Anyone can copy this text and paste it on their Facebook wall. This will place them under the protection of copyright laws.

Sarah Abdurrahman: I, for one, did not post that Facebook disclaimer on my wall, because I don't have a Facebook wall. Staying off the social networking site is my way of asserting control over my digital identity. Then again, I'm also guilty of using a diet Coke to wash down my metaphorical Big Mac. I may be off Facebook, but I use Gmail, have a smartphone, communicate over Skype, pay bills online. It's all just too convenient.

For On the Media, I'm Sarah Abdurrahman.

Bob: Coming up, government surveillance is on the rise, but if you've done nothing wrong what have you to hide?

Brooke: Or is that even the right question?

Brooke: This is On the Media.

Brooke: This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Bob: And I'm Bob Garfield.

Recently, the Wall Street Journal uncovered a privacy story reminiscent of the days immediately after September 11. Here's Fox News.

News Announcer: A disturbing new report claiming that the Obama Administration has launched a counterterrorism plan to gather information on millions of innocent Americans, including people not suspected of any crime.

Bob: Since March, a little known government agency called the National Counterterrorism Center has been allowed to gather information about you from any government database that it deems, quote, "Reasonably believed to have," quote, "terrorism information": data like flight records, casino employee lists, or the names of Americans hosting foreign exchange students. While programs like this have been suggested before, they've never been implemented because privacy advocates have persuasively argued against surveillance of citizens who are not under suspicion. Now that that data can be collected and retained for up to five years, that argument no longer prevails.

Also, now such data can be shared with foreign governments. Wall Street Journal reporter Julia Angwin explained why this represents a dramatic shift in how the US intelligence community looks at its own citizens.

Julia Angwin: The general guiding principle in the intelligence community has been that surveillance abroad is fine. That's part of their job. But inside of the US, you'd generally want some reasonable suspicion before you started pulling somebody's file. But the National Counterterrorism made a successful argument that they should have that authority: to pull entire databases from other federal government agencies, copy them in their entirety, and keep them at the National Counterrorism Center to look for clues. They used to be prohibited from doing general searches. Now they've got an allowance to do pattern-based queries, meaning that if they feel that a pattern is that your name is Bob and you wear pink shirts then they'll pull all those people and that might be enough to put you on a terrorist lineup.

Bob:

I should observe at this point for our listeners that I'm wearing pink shirt, so that didn't come entirely from nowhere. It's a data point.

If this program had been revealed in the Wall Street Journal five years ago, when George W Bush was the president, there would've been marching in the streets. It would've been, "Aha, once again this administration has overreached. There will have to hearings. This must stop." And yet, we have a different administration now and there's scarcely a whimper. What's going on?

Julia Angwin: One things is that by the time the public learned about this program it was already signed into law and was in effect, so there was a feeling of "What can we do?" Also, politically there hasn't been a huge will to push back against the war on terror.

Bob: You've made what I think is a very trenchant comparison: the digital revolution versus the industrial revolution.

Julia Angwin: Yes. My hero of all time is Ida Tarbell, who was the leading muckraker in the post-industrial era, and at the turn of the century was writing these stories about Standard Oil and their incredible monopoly over oil and the extreme price gauging they were engaging in. Her series of muckraking articles led to the creation of anti-trust laws. At the same time, Upton Sinclair was writing about the factories and the abuses that were happening in slaughterhouses. They were really the watchdogs for this era, because at that time there was no OSHA and there were no anti-trust laws and there was great change going on in the economy, but there wasn't a regulatory structure to police it.

We're at this great moment where the information revolution has come. We've never been more connected. But we're just awakening to the dark side of it, which is this idea that we're going to live under total surveillance all the time and that our speech will be chilled by the fact that we're always worried about who's watching us. Right now, the role we're playing... at least I see myself and my colleagues at the Journal playing... is we're trying to police that. We're not saying that the internet is bad or that any of this information economy is bad, but here are the edge cases that we should consider. Where do we want the boundaries to be?

Bob: Have we had the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire yet?

Julia Angwin: I think we probably have not. The Cuyahoga River caught fire 12 times before the Clean Air Act was passed, so I think it takes a lot of repeated abuses before things change.

Bob: Julia, thank you very much.

Julia Angwin: Thanks for having me.

Bob: Julia Angwin covers privacy for the Wall Street Journal.

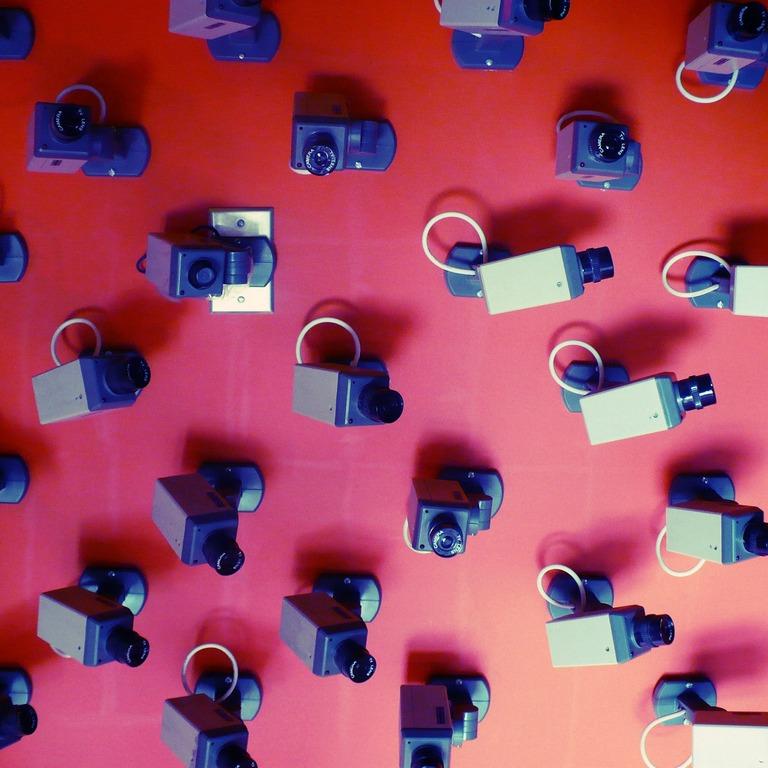

Brooke: In the ongoing debate over privacy, there's a common refrain that one side loves to repeat: "If you've got nothing to hide, you've got nothing to fear." The phrase was often invoked when the British government decided to install millions of public surveillance cameras across the country. And it's not only the refrain of government organizations. In 2009, Google's then CEO Eric Schmidt famously had this to say about your privacy on CNBC.

Eric Schmidt: If you have something that you don't want anyone to know maybe you shouldn't be doing it in the first place.

Brooke: But George Washington University law professor Daniel Solove says that this argument misunderstands privacy entirely.

Daniel Solove: People that privacy is just about keeping secrets when it's about a lot more. It's about basic control over very important information that could have an impact on whether or not you get credit or a loan. You might receive, for instance, different pricing on certain things. At the airport you might be subject to extra screening and you don't know if it's random or if you're on some list or what the reason is. Things can happen to you based on your information and you have no idea what data is being used why and how. You have very little recourse to do anything about it.

Brooke: Okay, but what about the classic and persuasive rejoinder that it protects us?

Daniel Solove: I hear this argument a lot; "Any security measure that's privacy-invasive must be really good." I don't think that's true. One example is the random searches in the New York subway. Out of about two million daily riders, they searched a handful of people. This program was an amazing waste of money and time that was largely symbolic. There's a term that Bruce Schneier,a famous security expert, uses called security theater.

Brooke: Security theater?

Daniel Solove: Yes: making it look like you're doing something that's really helpful, but it's not. It often leads to policy makers and others not really putting to the test various security measures and seeing if they're really effective. I don't believe in privacy at all costs, but I do believe that if people are asked to give up their privacy, they better get more security in return.

Brooke: Do you think we could resolve this issue if we were more transparent about our invasions of privacy?

Daniel Solove: Yes. I think more transparency and letting people in the know will help. And yet, one of the challenges when it comes to data mining for terrorism... which involves trying to determine whether people are engaged in patterns of activity that look suspicious... is that when you have that greater transparency you also tip off the terrorists as to what patterns people are looking for, and that's a tension. I'm not quite sure how you resolve this tension.

There are certain patterns we don't want to have the government using. What if the government uses things that you might say or read? What if they use religion? What if they use race? Certain things could be put into the profile that we as a society might think is not fair and not appropriate or even prejudiced to put in the profile.

Brooke: We don't live in China or Iran, North Korea. This isn't a surveillance society. Or do you think it is a surveillance society?

Daniel Solove: This is a surveillance society. The difference between us and China is that the government there is much more totalitarian. But the tools of surveillance that they have at their disposal are the same things that our government is using.

Brooke: Really? We don't block people from getting to certain websites.

Daniel Solove: We don't block. That's the difference. China blocks and China censors and China arrests in the middle of the night and throws you in a prison somewhere unknown. Actually, we do that too, we just don't do in the same extreme way that China does. But we do have all the tools of surveillance. We have drones that patrol the skies. We have tracking of the internet. We have the NSA surveillance program listening in on people's phone calls. I don't think that there's a very high risk that our government is going to become totalitarian in the sense that China's government is totalitarian, but what I do think is that it could affect certain groups, certain types of activities, and it's hidden. That has some totalitarian implications, but just for those people. So hey, if you're not on list, great for you. But if you happen to be on that list, now you're in a different world.

Brooke: You said that you're not a privacy absolutist. How would you resolve this issue?

Daniel Solove: By having real balancing between privacy and security. If we understood privacy better and didn't reject it out of hand and we actually had real scrutiny over the surveillance we could have our security and our privacy, too.

Brooke: Daniel, thank you very much.

Daniel Solove: Thank you.

Brooke: Daniel Solove, law professor at George Washington University, is author of Nothing to Hide: the False Trade Off Between Privacy and Security.

Brooke: Phillip C. Bobbitt is a former director for intelligence programs at the National Security Council. In his 2008 book Terror and Consent: the Wars for the 21st Century, he argues that data collection is an incredibly useful tool that's fundamentally misunderstood by the public. Take, for example, the alarm over warrantless wire tapping.

Phillip C. Bobbitt: There seems to be an assumption in the public debate that warrantless surveillance is lawless surveillance: that the 4th Amendment requires warrants before you can intercept a conversation or surveil somebody. The court has held that searches in public schools don't require warrants. Government offices can be searched for evidence of misconduct without warrants. Searches can be conducted at the border. Searches can be undertaken as a condition of parole without warrants.

Brooke: Many legal scholars have found there is 4th Amendment support for their position that it's illegal. Many have noted that the president has neatly resolved this issue by simply proposing and passing bills that made legally dubious practices legal.

Phillip C. Bobbitt: We have a way of resolving these things. We don't put it in the hands of the president. As you say, this is an act of Congress, so majorities in both houses thought it was constitutional. It will doubtless be challenged in the courts and judges will rule on whether or not they think it's constitutional. This is a statute and it's either lawful or it's not.

Brooke: You've also said that the need for warrants reflects an outdated criminal justice paradigm for building a case, and that's not what the NSA and the other government surveillance agencies are doing.

Phillip C. Bobbitt: That's exactly right. The warrant requirement is for criminal prosecutions, and that is a law enforcement paradigm that has served us very well. The problem is that if you're trying to preclude and attack, then you're not trying to punish someone for something they have done; you're trying to anticipate an act that has not yet taken place. I think it reminds you of the fact that we knew the identity of two terrorists: Al Madar, whose name was on a watch list... we had photographs of him leaving a terrorist meeting in Kuala Lumpur... and Al Hamsie. If we had simply taken their home addresses, their credit card accounts for the purchase of airline tickets, their frequent flier numbers, and their cellphone numbers, we would've picked up all 19 other hijackers and the fact they were all flying within an hour and a half period on September 11.

Now, it's not a crime to buy an airline ticket, but we would've prevented that atrocity just by cross-hatching the information we had on these other 17 with the two men we did believe were terrorists.

Brooke: But those people were already flagged. One of them had left a terrorist meeting. Looking up his associates would seem to make perfect sense, even if the rules prohibited it. But we're talking about a massive sweeping of information. The Wall Street Journal has just reported on another set of rules recently implemented that allows the National Counterterrorism Center to examine the government files of US citizens for possible criminal behavior even if there's no reason to suspect them, and that's apparently new.

Phillip C. Bobbitt: I don't see what the National Counterterrorism Center would be doing with these... as you say... hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of data points if they were not trying to connect it to known terrorist activity. How would they get a start? How would they ever navigate through this incredible maze of information? The only way that that kind of data mining makes sense is if you already have some strong lead.

Brooke: A few minutes ago we heard from George Washington University law professor Daniel Solove who's worried that information that's collected about us for one reason could be applied to some other unrelated purpose and that we'd never know.

Phillip C. Bobbitt: He makes a excellent point. I'd go one step further. I'd say that we ought to be using these very sophisticated techniques of automatic data mining and cross-hatching to protect privacy. The cross-hatching initial looking for patterns ought to be done by machines so that no one knows anything about any particular person. The retrieval of that information with an identity ought to go before some exterior tribunal to show that there really is a hard data point that justifies that.

Brooke: You would advocate anonymizing the data until a suspicious pattern emerges, and not putting a name to the data until there's some oversight from a different body?

Phillip C. Bobbitt: Absolutely.

Brooke: He's also concerned that the government might use criteria to build profiles that we as a people have deemed inappropriate, like a person's race or religion, and that it could be used to target certain groups.

Phillip C. Bobbitt: In light of some of our past abuses of power, that also is not an unrealistic fear, and I think we have to address those fears the way we have in the past: by building in legal processes and now building in technological processes that prevent that.

Brooke: I guess it all comes down to trust in government. When this data exists it can be abused.

Phillip C. Bobbitt: That's right. Now, the question is do you decide that there's nothing we can do other than not use these data mining techniques? I think that's very unrealistic and not a very helpful way to manage the security of our people.

Brooke: Do you believe that it's essential?

Phillip C. Bobbitt: I certainly do. Abdulmutallab was the underwear bomber. A subsequent Senate investigation into his plot showed that the National Counterterrorism Center did have hard information about it... that the problem wasn't a failure to share intelligence among the various entities... but that the National Counterterrorism Center was not organized adequately to fulfill that mission, because it did not query other government databases. Remember, this is not information that is collected by the government without your consent.

Brooke: Casino employee lists, the names of Americans hosting foreign students?

Phillip C. Bobbitt: That's right. This is information that we have provided the US government, not information that they went out and surveilled us to find out, and that is... I believe... the political impetus for this most recent round of trying to integrate government information.

Unless you're prepared to say that data mining is useless in these areas, when it so clearly could've prevented 9/11 with the most rudimentary techniques, then I think you've got to move on to those other questions: what can we do to give our people confidence that it's not being abused? What I sense is bewilderment as to why the Congress would pass this statute in the first place. They get a barrage of hysterical attacks from our major newspapers, perhaps even on programs like this one. Remember, the statute was passed by big majorities in both houses. It was a bipartisan act. And the persons who supported, for example, the FISA reform are among the most respected people in American life.

Brooke: Some say that it's just political death to appear to be pulling your punches on terrorism: the majority would rather vote for somebody who would stop at nothing to prevent terrorist acts, even if it seemed to roll back assumptions of privacy that Americans have.

Phillip C. Bobbitt: If the public wants to be more secure by changing their expectations of the data that is now brought to all of us across these new technologies, that seems to me to be a pretty sophisticated decision.

Brooke: Okay. Thank you very much.

Phillip:

Thank you.

Brooke:

Phillip Bobbitt, law professor at Columbia University, is author most recently of The Garment of Court and Palace: Machiavelli and the World that He Made.

Bob: Coming up, why one man's response to undo government surveillance has been to surveil himself.

Brooke: This is On the Media. This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Bob: And I'm Bob Garfield.

There is a legal device that is used by the US government to obtain personal information about citizens called the national security letter. These are essentially subpoenas with a lifetime gag order attached: a serious gag. You can't tell your lawyer, you can't tell your business partners, or even your family. Out of hundreds of thousands of recipients, only three people have ever won the right to disclose that they got a national security letter, chief among Nicholas Merrill, the owner of a small internet service provider called Calyx in New York.

I spoke to Merrill in 2011 and asked him to tell me about being on the receiving end of a national security letter.

Bob: So paint me a picture here. Is this like a Law and Order episode where someone says your name in a locker room or something and you turn around and he throws you an envelope and says, "You've been served"?

Nicholas Merrill: It was a little more formal than that. I was at my office. It was 2004. And I got a telephone call. The caller told me that they were with the FBI and that somebody would be coming by my office with a letter for me. Soon enough, I found out that it wasn't a joke when an actual agent did arrive and handed me an envelope. Inside there was a three-page letter. You can actually view it at aclu.org/nsl. Basically, the letter ordered me to produce information about one of the clients of my ISP.

Bob: What did you do next?

Nicholas Merrill: What I did right at that very moment was simply read the letter. A number of things lept out at me. The first thing was completely absolute commandment that I was never to tell anyone.

Bob: Not even your lawyer?

Nicholas Merrill: Your reaction just now is very close to my reaction. I looked at the agent and I said, "Not even my lawyer? Not even my business partners?" The agent just kind of shrugged.

Bob: What happened next?

Nicholas Merrill: The agent left. I tried to make sense of it all. One of the first things that I was looking for was a judge's signature or which court this supposed subpoena had come from, and there was none. So I called my attorney, my feeling being I'm an American and I can always talk to an attorney and no one can tell me that I can't. He was a bit taken aback. Coincidentally, one of the clients of my internet service provider was the New York branch of the ACLU, so we got in touch with them.

Bob: So not only are you not telling anybody, now you're telling everybody. You go to the ACLU and they advise you what?

Nicholas Merrill: They told me they had never seen one before. At that point, I knew this was really serious and I started to wonder what had I gotten myself into.

Bob: Did you comply with the other parts of the order to turn over the information to the FBI that they were seeking?

Nicholas Merrill: No, I never did.

Bob:

And the court ruled in your favor but not entirely. What was the gist of its decision?

Nicholas:

It was the first time anyone had ever challenged any of the powers from the USA Patriot Act. The court ruled two separate times that the national security letters provision is unconstitutional and a violation of the 1st Amendment, the 4th Amendment, and the 5th Amendment.

Bob: Before we get to the current legal disposition of your national security letter, let's talk about the government's concerns. Let's say one of your internet clients at the time was a terrorist. You would not want to tip such a person off that the feds were on the trail. If not a secret subpoena, what is the solution?

Nicholas Merrill: It seems to me that the existing tools, such as normal subpoenas from a judge, are workable. Numerous terrorism plots have been broken up using those types of tools. If we don't have checks and balances, then we're really going down a dangerous path. The purpose of having a judge listen to the evidence from law enforcement is to provide a check on their power.

Bob: Okay, so back to your disposition. You ultimately won the right to disclose that you had received this letter, but you didn't win the right to disclose everything. In fact, even as we speak you are holding in your lap a laptop with a six page single-spaced checklist of things you are or are not allowed to say, lest you wind up in Leavenworth. How ungagged are you at this point?

Nicholas Merrill: The way I try to explain it to people is that if before I was partially released from the gag there were 100 things I couldn't talk about, right now there are probably 97 things that I can't talk about. The main things that I won the right to say are that I was the plaintiff in this case and that I received a national security letter. During the six years when I couldn't say anything, I couldn't tell my family, I couldn't tell my fiance, I couldn't speak to my elected representatives. It sometimes forced me to even lie to people. That was a real problem for me.

Now that I can least say that I was the plaintiff in this case, it's somewhat of a relief. But at the same time, people ask me things that I can't answer. I've been warned that I should be really careful because anything I say is probably being listened to, particularly public statements. I respect that even within the privacy of my own home because it's a huge risk.

Bob: It turns out that you're kind of a poster child for a very large group of people. Do you feel a burden of responsibility that you're speaking for this gigantic cohort of the gagged?

Nicholas Merrill: Between 2003 and 2006, around 200,000 of these letters went out. That works out to be nearly one letter per 1,000 Americans. Although you're allowed to challenge the gag every year now under the new revised law, the last time I did it the government prevented secret evidence that only they and the judge could see, and my attorneys could not see and therefore could not challenge. It does add up to a lot of responsibility and that's part of what motivated me to start my nonprofit organization, the Calyx Institute. Part of it is to defend people who are gagged, part of it is also to promote best practices among telecommunication companies in regards to the privacy of customer data.

Bob: Nick, thank you so much.

Nicholas Merrill: All right. Thank you very much for having me on the show.

Bob: Nicholas Merrill is the founder of the Calyx Internet Access Corporation and of the nonprofit Calyx Institute, which works to put encryption tools solely in the hands of ISP users. Thus, an ISP would have no access to readable client data that a national security letter might demand.

We move from the most secret of secrets to what may be too much information. Increasingly, law enforcement agencies all over the country are using license plate readers... car-mounted infrared cameras that capture the license plate numbers and the date, time, and location information of every car they pass... in order to catch violators in real time. But even if you obey the law, your whereabouts at any moment in time could well be being logged by these cameras.

In August of this year, I spoke with Eric Roper of the Minneapolis Star Tribune who filed a couple of Freedom of Information Act requests for license plate reader information. It turns out... never mind the cops... anyone and everyone has access.

Eric Roper: What we found is that 4.9 million plates have been scanned in Minneapolis just in 2012. The vast amount of the data is on people who have not violated any laws but are just driving around the city. You can make a request of what now happens to be public information. The information on my car, which I requested... We received a number of data points that the police had kept over the course of a year, but also the information of the mayor of Minneapolis. His information was also public. There isn't a state law... and this is the case in most states... governing how we keep this data, how long, so it's left up to local law enforcement agencies who can use it as they see fit.

Bob: Now, the principal use of this is to find people without outstanding warrants and stolen car reports and so forth. To your knowledge, have the police used the data to investigate an individual who they are interested in for perhaps something more significant than traffic fines?

Eric Roper: The police have said that they do use what's stored in that database to help them with investigations. An example that they provided to me was that they were looking for a suspect and looked at his license plate reader data and found that he was parked at a certain location repeatedly. That gave them a place to begin in trying to find him.

Bob: Hence tbe impulse to keep the data for a year instead of two days.

Eric Roper: Exactly.

Bob: On this program, we are almost reflexively in favor of sunshine: that whatever the government is collecting the public should have access to. But it frankly terrifies me that as a private citizen I have access to essentially the tracking records of other private citizens.

Eric Roper: And that's what's so ironic about this program. It's not something that people generally know about. But here in Minnesota that data is public. Now, each state... it will depend on record requests there to find out whether the state open records preclude any of that, but you find that there's almost too much transparency when it comes to license plate data on a program that we haven't known much about up until now.

Bob: I mentioned the availability of this data to third parties. Now, that might mean a reporter interested in where the mayor has been, and it could be someone whose business has an interest in where your car is at any given time. You know of one such case.

Eric Roper: There was one car dealership that sells cars to people with bad credit. Those people had stopped paying for those cars and now it was trying to repossess those cars. Some repo men were looking for their cars and figured this was a perfect opportunity to do that.

Bob: What's troubling is that there may be people even more sinister than repo men... people operating outside the law... who might have an interest in my driving patterns.

Eric Roper: Right. One of the most prominent voices on this, who is a chief information officer for our public defender service, he brought up the examples of ex-spouses and stalkers and people who are looking to burglarize people. He really feels like there are some major public safety implications here.

Bob: So which of On the Media's hobbyhorses should rise to the fore here? Should it be our sense that personal privacy is sacrosanct and that nobody should surrender it by accident, especially to the government? Or should it be that government transparency should be the overriding social good, and therefore if we surrender a little privacy in the bargain it's no big deal? Or is there some middle ground here?

Eric Roper: I think the first step with regard to transparency is having a public discussion at legislatures, at city councils, at the federal government level, perhaps, about this technology. That at least allows people to understand what's out there and how it's being used. From there, decisions can be made about whether it's private or public and how it can be shared. I think transparency start with having a public discussion. That seems to be just beginning.

Bob: Eric, many thanks.

Eric Roper: Thank you very much, Bob.

Bob: Eric Roper is a report for the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

Brooke: And now we move from what may be too much information to what definitely is too much information, by design. In 2002, artist and Professor Hasan Elahi was detained at Detroit Metro Airport by the Immigration and Naturalization Service. Somehow, his passport had triggered a terrorism alert and he spent the next six months in and out of interrogation rooms sharing every detail of his life, which as a compulsive record keeper he had. Thanks to that wealth of personal information he was cleared, whereupon Elahi began trackingtransience.net. He calls it an experiment in self-surveillance. Essentially, he inundates the FBI and the rest of the world with his personal data.

When I spoke to him in 2011, I asked him to start by telling me what happened when he got off that airplane at Detroit Metro.

Hasan Elahi: It was absolutely something out of a movie. I come out of the airport, I hand my passport over to this guy, and he blinks and takes me through this rat maze at the Detroit Airport and I'm in an INS detention facility. It was there I was met by an FBI and the FBI agent asked me all sorts of details about who I was with, why I was there, who pays for my trips. Every little detail. Then he asks me out of nowhere, "Where were you September 12?"

Brooke: 2001?

Hasan Elahi: Exactly. This was in June of 2002, so it was shortly after. They had received an erroneous report that an Arab man had fled on September 12 who was hoarding explosives. Nevermind I'm not Arab. Nevermind it wasn't the 12th. Nevermind there were no explosives there. But we're going under this approach that if you have a Muslim name then you must be Arab and if you're Arab then you must have explosives.

I think he realized that I was no threat and he let me go. He said, "I'm going to pass this along to the Tampa office. They're the ones that imitated this. They'll follow up with you and we'll get this cleared up."

Brooke: And you asked him for a letter stating that you weren't guilty of any crimes but the FBI wouldn't give it to you.

Hasan Elahi: I travel a lot. As an artist, you go wherever there's work. So I said to them, "Guys, all we need is the last guy at the last airport not to get the last memo and here we go all over again."

Brooke: Why wouldn't he give it to you?

Hasan Elahi: The problem is in order to be formally cleared you have to be formally charged. As Americans we tend to think that we have these rights and these proper legal procedures, but when it comes to terrorism and national security frankly all that goes out the window. In this case there was no law, so at that time they couldn't really issue a statement of any kind. So they said, "If you get into trouble, here's some phone numbers. Give us a call. We'll take care of it."

I would call the FBI and I would tell them, "This is where I'm going," not because I had to but because I chose to. I started creating this little device that would share everything about me, and then I basically turned my phone into a tracking device, into something similar to an ankle bracelet, so everyone... including the FBI... would know where I was at any given moment.

Brooke: Let's talk about the sort of stuff you sent. Random hotel beds you'd slept in. Parking lots you've parked in. Photos of tacos you ate in Mexico City between July 5 and July 7. Pictures of the toilets you use.

Hasan Elahi: I've come to the realization... "Guys, you want to watch me? That's fine. I'm okay with that. But you know what? I can watch myself better than you guys ever could." That's what was really exciting about this project, is that it turns the surveillance upside down on its head. Intelligence agencies... and it doesn't matter who are they are... all operate in an industry where their currency is information and it's the restricted access to the information that makes that information valuable. By me borrowing the simplest of all economics principles and flooding the market, the information that the FBI has about me has no value whatsoever.

There are so many different databases that go up there. I'm hoping that the viewer has to through the role of playing the FBI agent and cross-referencing this database with that database and in that detective work coming to the realization, "Wait a minute. This could be me."

Brooke: And then what are you supposed to conclude?

Hasan Elahi: Hopefully we'll come to the idea that we're in such an absurd age... the way we think of government surveillance, the way we think of wire taps... and the only way you can counter such an absurd system is by going even further absurd with this. I mean, when you're looking my photos and you're seeing all the toilets and all the food and all the beds, there is a sarcastic, comedic side to it, but at the same time I'm talking about something incredibly serious. Instead of fighting this, I can comply, maybe even to the point of aggressive compliance. By doing that, it actually neutralizes this whole situation.

Brooke: And yet, you've written that your server logs indicate repeated visits from the Department of Homeland Security, the CIA, the National Reconnaissance Office, and the Executive Office of the President. You have everything out there, so what are they looking for?

Hasan Elahi: This baffles me. Maybe it's just someone being curious. Maybe it's just, "Hey, check out this guy that's doing this wacky project." On the other hand, what if it's not? The hits are frequent enough to make me concerned. It's hard to say you're paranoid when you actually have proof that they are watching.

Brooke: Hasan, thank you very much.

Hasan Elahi: Thanks for having me.

Brooke: Hasan Elahi is an associate professor and interdisciplinary artist at the University of Maryland.

Bob: That's it for this week's show. On the Media was produced by Jamie York, Alex Goldman, PJ Vogt, Sarah Abdurrahman, Chris Neary, and Doug Anderson, with more help from Krista Ripple and Annie Russel. It was edited by Brooke. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Ken Feldman.

Brooke: Katya Rogers is our senior producer. Ellen Horn is WNYC's senior director of national programs. Bassist composer Ben Allison wrote our theme. On the Media is produced by WNYC and distributed by NPR.

Brooke: I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Bob: And I'm Bob Garfield, but don't tell anybody.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.