Using Conspiracy Theories to Make Sense of a Loss

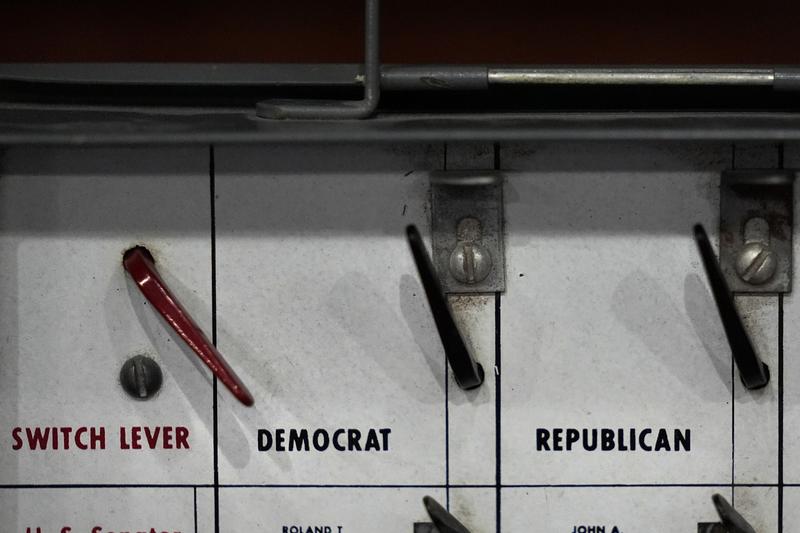

( Charles Krupa / AP Images )

Micah Loewinger: Hey, you're listening to the On the Media midweek podcast. I'm Michael Loewinger.

On election night, when things started looking not so great for Kamala Harris, and then when Donald Trump was declared the clear winner of the presidential election early Wednesday, there were the expected social media posts questioning the election results. This time, many were coming from Democratic voters.

Speaker 2: Not to be a conspiracy theorist, but there's a couple things that I've been seeing on TikTok over the last couple of days, and I want to just put it all in one video of the things that are suspicious. You can do with this information what you want, but I think when you look at it all together, it's--

Speaker 3: How could all of the swing states voted in Democratic governors, senators, and President Trump? Where are all of the votes if there was record voter turnout that didn't end up turning into votes?

Speaker 4: I wasn't going to chime in on all the math, not math, and stuff, but remember this data breach that happened three months ago that was massive? Did anything ever happen with that? I wonder what someone could do with a whole bunch of names, Social Security numbers, phone numbers.

Micah Loewinger: Some of the posts went viral, but without boosts from election officials like in 2020, these bogus stories of election fraud will likely or hopefully fizzle out. Anna Merlan is a senior reporter at Mother Jones covering disinformation, technology, and extremism. She says it's to be expected that people will turn to conspiracy theories to try to make sense of a loss they weren't prepared for.

Anna Merlan: The best example is the 2004 election. John Kerry lost to George W Bush, and a big thing that happened in that election was that the exit polls were super, super wrong. Pretty much every exit poll seemed to predict a Kerry victory, and there was a lot of postmortem devoted to this, why were the exit polls so wrong. Some people turned to an explanation of fraud, including, ironically enough, Robert F Kennedy, Jr.

Micah Loewinger: He wrote a piece in Rolling Stone to this effect, right?

Anna Merlan: He did, yes. It was very widely viewed and discussed, but, in fairness, he was not alone. Now, of course, Robert F Kennedy, Jr. is serving on Trump's transition team and expected to play a role in a second Trump administration.

Micah Loewinger: In 2024, what kinds of conspiracy theories from Kamala Harris supporters are you seeing, either from election night or in the days following?

Anna Merlan: There's been a disconnected set of concerns that center around essentially some of the same things that happened in 2004, like how could the pollsters be so wrong, how could this massive Democratic turnout among youth voters and women not count. Then there are people who are very specifically, explicitly saying, "I believe the election was hacked and stolen by Elon Musk through Starlink," a company that's owned by SpaceX, or, "I believe that Putin somehow stole the election." I would say that that one is a little bit less common.

It's this general sense of something not being right. Another big one is this idea that votes are missing. The number that's often [unintelligible 00:03:17] around is 20 million votes. All of it is essentially adding up to Harris supporters saying, "This doesn't make any sense to me. I think the Harris campaign needs to demand a recount." That's essentially broadly what I'm seeing.

Micah Loewinger: Was the polling wrong in this election? It seemed like much of it was within the margin of error and predicted an extremely tight race. That's what we got.

Anna Merlan: Yes, exactly. The polling was conflicted, but most of it, the overwhelming majority, showed that these candidates were going to be in a dead heat, and that is indeed what happened. I think that some polls had a slightly more optimistic outlook for Kamala Harris, and I think those are the ones that her supporters are looking at when they're saying that these results don't make sense to them.

Micah Loewinger: You quoted one man named Wayne Madsen, who you describe in your piece as a former journalist and documented conspiracy theorist who posted on Threads, the social media site, writing, "I'm beginning to believe our election was massively hacked. Think Elon Musk, Starlink, Peter Thiel, Bannon, Flynn, and Putin. 20 million Democratic votes don't disappear on their own."

Anna Merlan: I'm not completely clear on exactly what the theory is here, but generally, there seemed to be an impression among some Harris supporters that Starlink was in some way being used to tabulate votes, which is not correct. It's not used that way. Thus, in some way, Elon Musk would be able to use Starlink to change voting results. Again, too, he's not pulling together one unified theory here. He's just throwing out the names of people whom he believes would have caused to engage in election interference.

Micah Loewinger: There was a viral TikTok video, which has since been taken down, that I think helped fuel the Starlink conspiracy theory.

Speaker 6: Number 1, why in the flying freaking flap were voting ballot boxes or whatever, the places where you go to vote, why were they connected to the Internet? There is absolutely zero, zero reasons as to why those systems were connected to the Internet.

Anna Merlan: The two main flavors of videos on TikTok have been stuff from people identifying themselves as experts in tech in some way, or working in IT in some capacity, and then, weirdly enough, psychics and people in the psychic community saying that something is just not adding up from an astrological perspective. I don't mean to make light of it, but that's what's going on.

Speaker 7: Will Kamala Harris be President of the United States? I'm not just going to tell you, I'm going to show you. This is Harris's birth chart. This is what was promised at the time of her birth. Kamala Harris is a Gemini rising, making Mercury the lord of her chart. Mercury is placed in Scorpio in the sixth house.

Micah Loewinger: You could hop onto Twitter threads, TikTok, Instagram, any day of the week and find people saying unsubstantiated stuff about current events. How popular is this, really?

Anna Merlan: I don't think that it is an overwhelming point of view among Harris supporters, or people on the left, or Democrats. That is not the sense that I get. It is a substantial and vocal minority, and certainly enough that the AP, for instance, has had to put out a fact checking piece on the fact that some rural communities use Starlink as an Internet provider, but their voting equipment is not connected to Starlink. Election officials in multiple swing states have had to reassure people that this didn't happen.

While I would say that there is a substantial minority of Harris voters who are engaging in this general conspiracy theorizing sense of something doesn't add up, what I think is important to note is that it's not driving official policy or an official response from the Harris campaign from the Democratic Party, that's not happening. There is no one that I can find who is in any position of power whatsoever in the Democratic Party or the Harris campaign who's taking this seriously or suggesting that they believe that there's any kind of fraud that took place.

Short of that, election officials and officials at CISA, which is the federal agency responsible for cyber defense, have said that they believe this was an incredibly secure election.

Micah Loewinger: To your point, Kamala Harris conceded quite quickly after she lost the election. Donald Trump never conceded after he lost the election in 2020, and used the big lie to justify a violent mob storming the Capitol to block certification. Certainly we don't want to draw a false equivalency here.

Although from some of the media coverage I've read, it would seem that this is a small but growing phenomenon among Democrats. So much so that the Internet and a growing number of media outlets are reviving an old term to describe this kind of conspiratorial thinking.

Speaker 8: Is the left starting to go partial or full QAnon? BlueAnon, if you will?

Speaker 9: BlueAnon? What are y'all doing? I'm not coming down there with y'all. How y'all get way over there?

Micah Loewinger: Where does that term come from, and how do you feel about it?

Anna Merlan: The term BlueAnon, it first started being used in 2016 to refer to a loose collection of conspiracy theories about Donald Trump, conspiracy theories that he was a literal Manchurian candidate or a Russian agent who was acting solely at the behest of Putin. It's recurred several times since then in different forms as a reference to crackpot theories from the left. I think actually, Marjorie Taylor Greene was one of the first people to use it in public life.

I don't know how I feel about it. I don't think it's a very descriptive term. I understand what it's trying to do, but I don't know. Unless we can all agree on exactly what it's referring to, I'm not sure it's super helpful.

Micah Loewinger: Yet members of the press are using it. I saw it used to describe conspiracy theories about the attempted assassination attempt on Donald Trump in Butler, Pennsylvania, basically saying it was a false flag operation where he engineered this attack to boost his standing in the polls. I also saw it used to describe conspiracy theories on Election Day that Donald Trump was walking around with a fake Melania Trump. Do you think members of the media should use the term?

Anna Merlan: I think if people want to use terms like that, they should explain what they mean. In the same way that if you are talking about QAnon or you are accusing someone on the right of being a conspiracy theorist, then you should explain what you mean. This points at a larger and more important point, which is that, as I've written about 1 million times and as many political and social scientists talk about, conspiracy theories really are for everyone. People engage in conspiratorial thinking on the left, on the right, and in politically undefined places. In this case, we see a really clear example of the ways that people, when they are facing a moment of loss, a moment of confusion, a loss of power, they engage in conspiratorial thinking.

Micah Loewinger: Beyond simply documenting the spread of conspiracy theories, which is worth doing in and of itself, I'm sure we both agree-

Anna Merlan: Sure.

Micah Loewinger: -do you buy into the narrative that an increasing number of Democrats are losing it online?

Anna Merlan: I don't think that the immediate aftermath of an election is a good place to determine that. I would want to see how it affects people's sentiments long term, people's voting patterns long term, whether folks are still, as is the case actually with some 2004 election conspiracy theorists, whether they're still clinging to this months or years later. What I do think is happening is that these theories are more visible for a couple of reasons. One is that everybody has access to social media and hashtags, and they can make their views known. The other is that these kinds of claims draw eyeballs. They draw attention. I've seen a number of TikTok videos that, to me, feel, not to be cynical, but a little bit like engagement bait.

Micah Loewinger: They're just phoning it in because the algorithm will deliver in turn.

Anna Merlan: I think it's more like it's encouraging their worst impulses. If you want to engage in a suspicion mindset and you'll be rewarded, you'll be agreed with, you'll get views. If you are monetizing your social media in some way, you might literally make money. It's not a bad deal.

Micah Loewinger: There are clear incentives.

Anna Merlan: Yes.

Micah Loewinger: I want to focus on some of the election conspiracy theories we have seen from the right. In Arizona, Trump won the vote, but down ballot, it took a few days for the race to be called for the Senate race between Democrat Ruben Gallego over Republican Kari Lake. What did you see in terms of conspiracy theories here?

Anna Merlan: I saw this especially on Truth Social and Twitter, where folks were starting to suggest that voter fraud was occurring, first of all, against Donald Trump, because it took Arizona, I believe, a few days to call the election. In those few days, I saw sentiments starting to circulate on Truth Social and Twitter that the fix was in and that there was an effort underway to steal Arizona from Donald Trump, which doesn't make any sense. He had already won the election by that point. Arizona was not necessary to his victory.

Then we also started to see this sense that maybe there had been voter fraud in down ballot races in Arizona and also elsewhere. One of the big examples was Democrat Ruben Gallego triumphed over Kari Lake in Arizona's Senate race. A number of prominent conservative commentators said that this was maybe evidence of down ballot fraud. Somehow, the fraud had succeeded in the Senate races, but not in the presidential race.

Micah Loewinger: I love how the claims have gotten narrower and narrower. We saw, for instance, Elon Musk's Election Integrity Community, a sort of clearinghouse of yet to be proven or disproven claims of irregularities in the vote on X, just a place for people to just dump rumors so that they could go viral. After the election, Donald Trump's supporters were relatively silent, and the explanation I've seen over and over is that I guess somehow people are paying more attention to the vote this time around, and so Democrats didn't think they could steal it or something. It was too big to rig or something like that, and yet we still see conspiracy theories applied selectively to races where Republicans didn't win a clear majority.

Anna Merlan: Yes, it's actually important to note that too big to rig is a phrase that Donald Trump coined to explain why he managed to win. Yes, two things are happening here. One is, as my colleague, Julianne McShane, wrote about, the Election Integrity Community, following the presidential election being called, was very, very focused on Arizona and on that Senate race between Ruben Gallego and Kari Lake, basically saying that the election was suspiciously close for a red state, and thus it must be in the process of being stolen.

The second thing that happened is that folks like Donald Trump and Alex Jones also made this claim that the margin of victory for Donald Trump was simply too overwhelming, and so while the Democrats attempted voter fraud, this time they did not succeed because it was, as Trump put it, too big to rig.

Micah Loewinger: Tell me about pro-Trump and left wing conspiracy theories that were focused on Pennsylvania.

Anna Merlan: Pennsylvania was super interesting because this was obviously the main battleground state that folks were watching. There were reports from multiple conspiracy peddlers that trucks full of blank ballots were being brought to Pennsylvania overnight. I saw this circulating pretty widely on Telegram, a kind of major force in the conspiracy universe who runs a conspiracy site called Natural News, made this claim trucks of ballots were seen unloading in Pennsylvania. Trump actually also made this claim. He said there was massive cheating underway in Philadelphia, and that law enforcement was on the way. Then he won Pennsylvania and he never repeated it.

Micah Loewinger: Maybe he just forgot.

Anna Merlan: Not to be flippant about this, but yes, in a very real sense, it didn't serve him to talk about massive cheating anymore after he won Pennsylvania. It's not not helpful. It would not make any sense to return to that claim, to try to tie it up, to try to make it make sense. Again, we've seen this over and over and over with Donald Trump. He's made rigged voting and voter fraud a main tenet of his campaigns, of his public presence, the idea that he's constantly being plotted against, and that it requires a great deal of public support, and more importantly, donations to keep this fraud from taking place.

Micah Loewinger: It will be interesting to see whether his administration turns to voter fraud as a pretense for changing election laws.

Anna Merlan: Yes, it's entirely possible. Obviously, a lot of election reforms happen at the state level, so we will see what happens there. I think one important point to make is that throughout this election, the Department of Justice was publicizing attempted election interference, especially foreign interference. We heard a lot about, for instance, Russian state actors who were engaging in various attempted forms of fraud. We'll never know if those had any effect on the election, which is a separate question, but certainly the DOJ was talking about it. For me, one question will be the extent to which the Trump DOJ focuses on that stuff, or talks about it.

Micah Loewinger: I do want to look at Wisconsin. Republican Senate candidate, Eric Hovde, has yet to concede to Democratic incumbent, Tammy Baldwin. He posted a video on social media about how, among other things, Baldwin received a big push in absentee ballots, which were counted late on election night.

Eric Hovde: At 1:00 AM, I was receiving calls of congratulations, and based on the models, it appeared I would win the Senate race. Then at 4:00 AM, Milwaukee reported approximately 108,000 absentee ballots, with Senator Baldwin receiving nearly 90% of those ballots. Statistically, this outcome seems improbable as it didn't match the patterns from same day voting in Milwaukee, where I received 22% of the votes.

Micah Loewinger: He said that he's considering asking for a recount, but that, "There are meaningful limits of a recount because they don't look at the integrity of a ballot." What's the point of this play?

Anna Merlan: He's saying that a recount would not fully address what he called 'voting inconsistencies' and, what he said, the 'the integrity of the ballot.' Often when folks are making these claims, it is a fundraising effort, but it also really speaks to how deeply allegations of voter fraud and electoral misconduct are embedded in the way that many Republican candidates now talk about elections and election security. Again, I think it can be possible to grow numb to it, but Donald Trump has really pioneered this way of talking about elections and voter fraud by national candidates in the way that he does, making these very, very bald allegations of fraud. Now we're seeing it play out in a down ballot race.

Micah Loewinger: What kind of response have you seen from social media companies? Have they tried to keep this in check in any way? Have some been better than others?

Anna Merlan: There are a couple of things that happen. Some individual statements from some individual folks get subject to, for instance, community notes on Twitter. On TikTok, largely what I'm seeing is, in videos that discuss the need for a recount or talk about fishiness, or just videos that talk generally about the election, there is a link to look at real-time certified election results. It's not a commentary on the video per se or the truth or untruth of the video, it is just a link to election results so you can see for yourself.

Broadly, social media companies really threw in the towel on policing disinformation. This has been written about quite a bit, including by myself talking about things like Covid misinformation on Twitter. That has also, to a certain extent, applied to election stuff. There is simply so much of it, it's happening in so many different forms, and social media companies have really lost their appetite for policing this stuff in an aggressive way. I would say that a lot more of it is circulating than maybe we would have seen in 2020.

Micah Loewinger: Hopefully we put some of the so called BlueAnon conspiracy theories in context. I guess ultimately, are you concerned that election denialism is becoming an increasingly bipartisan problem?

Anna Merlan: I think in the short term, yes, I am a bit concerned that this is happening. We wrote about this Marist Poll that came out in October where I believe a majority of voters said that they were concerned about fraud or interference. A slim majority, it was 58% of Americans. I worry about that on a couple of levels. One obviously is folks not accepting the results of free and fair elections, I think would be just generally bad for the country. The other is that we have evidence that these types of conspiracy theories can actually dissuade people from voting and from other forms of civic engagement. People can decide, "If the system is rigged, why should I bother?" I think it would be a real loss if folks get disillusioned and disenfranchised out of civic participation.

Micah Loewinger: Anna, thank you very much.

Anna Merlan: Thanks for having me.

Micah Loewinger: Anna Merlan is a senior reporter at Mother Jones covering disinformation, technology and extremism.

Thanks for listening to the midweek podcast. Check us out on Bluesky, the Twitter/X clone that's received a huge number of new users since Election Day. It's a pretty nice place to read and discuss articles or whatever. Just search on the media to find our account. Oh, and don't forget to tune into this week's big show on Friday. We'll be discussing the FOX News to White House revolving door, and the past and future of the humble fact check. See you Friday. I'm Michael Loewinger.

[END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.