America’s Empire State of Mind

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: On this week's On The Media, how the map of the US we grew up with has never shown us our true selves.

Daniel Immerwahr: If you looked up at the end of 1945 and you saw a US flag flying overhead, it was more likely that you were living in a colony or occupied zone than you were actually living on the US mainland.

Brooke Gladstone: The origins of the American empire lie in the so-called guano islands in the Caribbean.

Daniel Immerwahr: I asked some historian friends, "What do you think is the worst job in the 19th century to have?" I think I can now say with confidence, guano mining is the worst.

Brooke Gladstone: America's holdings then expanded to include Samoa, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and elsewhere despite the claims of many a US president.

Truman: We do not seek for ourselves one inch of territory in any place in the world.

Brooke Gladstone: An Exploration of Empire after this. From WNYC in New York. This is On The Media. Micah Loewinger is out this week. I'm Brooke Gladstone. Donald Trump said last month on Meet the Press that given how much the US is "subsidizing Canada and Mexico" both nations should just become states. That was probably a joke, right? He seems dead serious about buying Greenland, ostensibly because of its location and resources.

Despite it definitely being not for sale, he also wants the Panama Canal, which belongs to Panama. We have this notion that the United States, being a republic and former colony, never was and never aspired to be a colonial power, but that is wrong. As you'll hear in this rebroadcast of one of our favorite shows, a conversation from 2019 with Northwestern University history professor, Daniel Immerwahr, author of How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States.

This masterwork was inspired by a trip he took some years earlier to the Philippines. He was stunned by what he found. Streets with American names, people speaking American English. Of course, he knew the Philippines had once been annexed by the United States, but until he saw it, he never understood what that really meant.

Daniel Immerwahr: I realized that the United States that I was teaching a history of was a truncated version. It was the contiguous United States, but that's not the whole country, and it's never been the whole country.

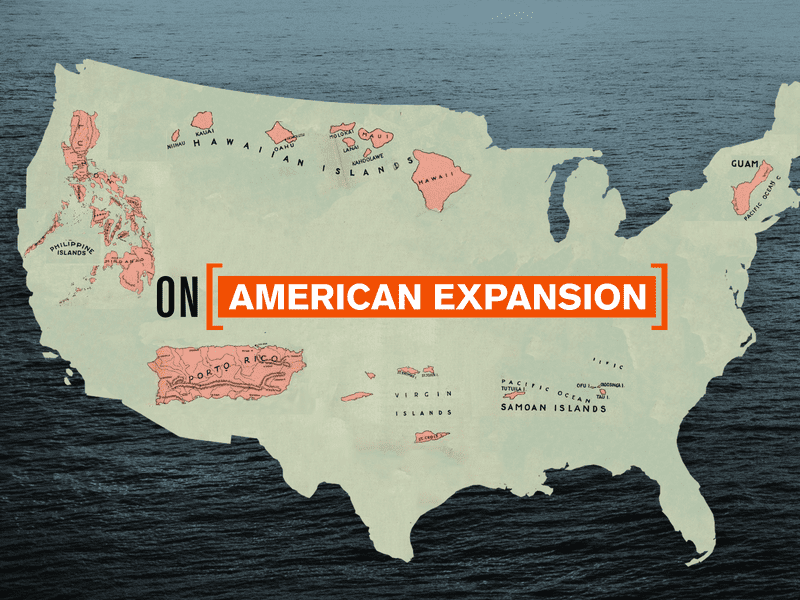

Brooke Gladstone: That whole country is almost always depicted by what he calls the logo map. The lower 48 spanning from coast to coast, jutting out in the southeast with a protrusion for Florida and a smaller one for Texas.

Daniel Immerwahr: That map, the contiguous blob with oceans on either side and Canada in the north and Mexico in the south, that's only been the borders of the United States for three years of its history.

Brooke Gladstone: Some of us never got past that truncated version of history we learned in primary school. To see the implications of that, we need only look back to October, when a comedian told this joke at a Trump rally in Madison Square Garden.

Tony Hinchcliffe: There's literally a floating island of garbage in the middle of the ocean right now. I think it's called Puerto Rico.

Reporter 1: Comedian and podcast host Tony Hinchcliffe made a so-called joke about Puerto Rico.

Reporter 2: This Puerto Rican has something to say about the island that I love. Where my family is from. Puerto Rico is trash. We are Americans, Donald Trump.

Donald Trump: I have no idea who he is. Somebody said there was a comedian that joked about Puerto Rico or something, and I have no idea who he was. Never saw him, never heard of them.

Brooke Gladstone: In 2018, Donald J. Trump drew criticism from many Puerto Ricans when he disputed the death toll of Hurricanes Maria and Irma and then--

Reporter 3: The White House spokesperson calls Puerto Rico that country while defending the President's treatment of the US Territory.

Brooke Gladstone: Puerto Rico's status as belonging to the United States seems to be thoroughly misunderstood by vast swaths of their fellow Americans. The path of how we arrived at this point starts in the 19th century when the population boomed and our soil was dangerously depleted. Turns out the best remedy for pasture that's pooped is nitrogen, and the best source of that is literal poop of the avian variety.

Daniel Immerwahr: In the 19th century, that bird poop, guano, was called white gold because it was seen as so valuable as fertilizer for farms that, once they'd converted to industrial farming, were losing a lot of their fertility. An acre of farmland that might formerly have grown 20 bushels of wheat was, by the mid and later 19th century, growing down to 10 bushels an acre. This was a serious crisis.

Brooke Gladstone: You need lots of usable nitrogen. There are whole islands basically made of this white gold.

Daniel Immerwahr: Islands in the Pacific and the Caribbean that don't get a lot of rain, but that do get a lot of visits from birds. Then they poop on the islands year after year after year and it piles higher and higher, bakes in the sun so that over centuries, you're looking at an island that is basically made out of fecal matter.

I asked some historian friends, "What do you think is the worst job in the 19th century to have?" I think I can now say with confidence, guano mining's the worst because it's like coal mining with all the pulmonary damage that you might suffer, except you essentially have to be marooned on a rainless island where there's only the food the ships can bring with them, very little water supply, where people are suffering from all kinds of intestinal illnesses as a result.

Guano entrepreneurs sell African American men in Baltimore a story about the tropical lives that they'll be able to live consorting with beautiful women, picking fruit, occasionally shoveling a little guano. Once the men step on that ship, their reality changes. Where else are you going to go? That ship takes you to the Guano Islands, deposits you there. You're under the supervision of a white overseer. You just have to work and they have to pay for their passage. The second they arrive, they are in debt to their employers and they have to shovel enough guano or blast it free from the island in order to pay for their return passage.

Brooke Gladstone: These workers were abused horribly, left tied up in the sun if they violated an order, and then something happens.

Daniel Immerwahr: To understand it, you have to understand the harsh regime of labor discipline on Navassa Island,

Brooke Gladstone: Off the coast of Haiti.

Daniel Immerwahr: Yes. This is an island that is full of Black men who've been deceived. They're not very enthusiastic about backbreaking work in the scorching sun on a jagged island. It's not a shock to me that these men mutiny, gather some rocks, weapons, and some dynamite, and they stage a full-out riot and they end up killing five of their white overseers. The papers all report it. Black men have butchered white men and they're hauled back to Baltimore for a trial.

Brooke Gladstone: Which becomes a milestone in America's legal history of imperialism. Ultimately, they win, but how?

Daniel Immerwahr: It's kind of incredible. The African American community in Baltimore rallies around them and their legal team make this extraordinary argument, which is to say Navassa Island isn't part of the United States. Because it's not part of the United States, federal law doesn't apply and if federal law doesn't apply, how can you try these men in US Courts? They're outside of the jurisdiction of the United States.

What this legal team does is it challenges the constitutionality of the idea that the United States can expand overseas. It goes all the way up to the Supreme Court and the Supreme Court has to decide, is the United States the kind of place that can expand overseas?

The court decides that, yes, it is constitutional right and proper that the United States should expand overseas. This minor incident on a place that had seemed very remote from the perspective of the mainland, suddenly lays the legal foundation for the United States territorial empire.

Brooke Gladstone: Also doesn't this decision thereby declare that what happens there is subject to American law? These companies that were mining the guano were also massively breaking the law.

Daniel Immerwahr: That's right. It cuts two ways. If these places are part of the United States, where do they go to appeal for justice? What are they supposed to do when they're being, as they are, clearly abused? Benjamin Harris concludes that, okay, yes, these places are indeed part of the United States, but that means that people working on them should have some appeal to all the institutions and courts of the United States.

He, as a result, takes this issue up and decides to commute the sentences so they're not sentenced to death. Then they have to spend the rest of their lives at hard labor.

Brooke Gladstone: It was the pursuit of guano that forced us as a nation to publicly acknowledge that we were going to expand beyond our manifestly destined borders into realms unknown. By 1898, most of America seems all in on this imperialism idea. Maps were redrawn and hung in classrooms across the country. Maps that we certainly didn't grow up with that showed us America in the world as it truly was.

Daniel Immerwahr: It's an extraordinary moment. In 1898 and 1899, the United States basically goes on a sort of imperial shopping spree. It fights a war with Spain, and as a result of that war, it takes the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico, and it briefly occupies Cuba. At the same time, almost in a fit of enthusiasm, the United States also annexes Hawaii and American Samoa. Cartographers see their opportunity and start publishing these extraordinary new maps. New maps that show the US Mainland surrounded by boxes, so Alaska, Hawaii, Guam, Puerto Rico, American Samoa. Why these are so extraordinary, at least for me, is when I saw them, I thought, "I've never seen a map like that." I had never seen a map of the United States that had Puerto Rico on it. I'd never seen a map of the United States that had that box for Guam. This is a moment when, and a lot of people in the US Mainland are so proud of this new facet of the United States that they are eager to see it differently.

I found books that have titles like The Greater United States, The Imperial Republic, the old way of referring to the country as the United States, the Republic, or the union in the 19th century, those don't really work anymore because it's now transparently not a republic and not a union. This new polity, quite transparently, has not been created by the voluntary entry of all parts. The Philippines fights a bloody war of independence that we think racks up more bodies than the US Civil War.

Brooke Gladstone: I remember there was a time when the US Was referred to as Columbia. In songs like Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean.

[MUSIC - Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean]

O Columbia the gem of the ocean,

The home of the brave and the free,

The shrine of each patriot's devotion,

A world offers homage to thee,

Daniel Immerwahr: Yes, because Columbia was in the way that we have the District of Columbia, Columbia was a literary name for the country. What's striking about this is the literary name that we all have in our heads that really wasn't that often used in the 19th century, America. A lot of people in the 19th century understood that if you were speaking of America, you were speaking of the Americas, the whole region. That changes in 1898, partly out of this desire to find a new way to describe the country, a new shorthand for it. America.

It's a vaguer, more expansive term. The President who takes office after the war with Spain. Teddy Roosevelt uses the word America in his inaugural address. There's a two-week period where he uses it in different speeches more times than every past president has used it collectively in the entire history of the country. Ever since then, it's off to the races.

Brooke Gladstone: Why was 1898 an Imperial shopping spree? What was going on?

Daniel Immerwahr: The United States bonked into the Pacific. The census in 1890 had issued a report suggesting that the frontier was no more. It inspired a few, such as Teddy Roosevelt, to try to make new frontiers, to find new places where the United States could restore its vigor.

Brooke Gladstone: Explain the Philippines.

Daniel Immerwahr: It partly has to do with Teddy Roosevelt. He's the assistant secretary of the Navy. His boss leaves the office for an afternoon to visit an osteopath and Roosevelt springs into action and orders the US Asiatic Fleet to prepare to invade Manila if the United States has a war with Spain and his boss doesn't countermand the order, possibly fearing looking weak. When the United States does go to war with Spain, it engages the Spanish fleet, defeats it, and suddenly the United States has the Philippines on its hands.

Brooke Gladstone: Not suddenly. Takes a while.

Daniel Immerwahr: Right. The actual conquest of the Philippines takes an enormous amount of time. Part of the reason the United States is in a good position vis a vis the Philippines is that the United States has allied itself with Filipino insurgents who've been fighting against Spanish colonialism for quite a long time. They think that they're doing so in the name of liberating their colony.

With the aid of the United States, they're able to conquer the archipelago. The United States ends the war by purchasing the Philippines from Spain but then it has to deal with these Philippine insurgents and ends up fighting a long and excruciatingly bloody war. The Philippine archipelago isn't restored to civilian rule until 1913 and was only recently surpassed by the Afghanistan War as the longest war in US history.

Brooke Gladstone: On what grounds did the US go to war for the Philippines? Because the US was still hesitant to say, "We do this for the sake of empire. "The US was never quite as frank about this as, say, the British were.

Daniel Immerwahr: Well, this is a really interesting and rare moment in US history where the leaders of the country will start talking like the British. The reason that the United States needs to fight the Philippines and fight to retain the Philippines is in order to civilize and uplift Filipinos. The most famous poem justifying empire, Rudyard Kipling's White Man's Burden, is written as advice to the United States about what to do in the Philippines.

Rudyard Kipling: Take up the white man's burden, send forth the best ye breed. Go bind your sons to exile, to serve your captives need to wait in heavy harness on fluttered folk and wild your new court sullen peoples half devil and half child.

Daniel Immerwahr: Teddy Roosevelt receives an advance copy, but a lot of politicians are deeply enthusiastic about this notion that the United States could achieve its adulthood by becoming like Britain, like France, a transparent and forthright empire that's taken on the white man's burden to uplift and to educate its colonial subjects. That's the rhetoric of the time.

Brooke Gladstone: You quote Mark Twain, who had been as ardently imperialistic as Rudyard Kipling, but then reversed himself, "There must be two Americas. One that sets the captive free and one that takes a once captive's new freedom away from him, picks a quarrel with him with nothing to found it on, and then kills him to get his land." For that second America, he proposed adding a few words to the Declaration of Independence. Governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed white men.

Daniel Immerwahr: That's right. Mark Twain and Kipling were friends. Initially, Mark Twain had been, as he described it, a red-hot imperialist. As he saw the war in the Philippines start to unfold, he came to be one of the most withering critics of the war, just as vociferously anti-imperialist as Kipling was pro-imperialist. For the rest of his life, he would chronicle with sarcasm, with outrage everything that the United States was doing in the Philippines. The massacres, the tortures, the hypocrisy.

Brooke Gladstone: Coming up, how the world's professed leading democracy learned to reconcile itself to imperial brutality. This is On The Media. This is On The Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. At the dawn of the last century, it wasn't just poets like Kipling and writers like Twain who are arguing about imperialism. In a world of shifting borders, the adolescent United States, big-headed about its democratic values, would grapple over how or even whether to grab other people's territory.

Back in 2019, historian Daniel Immerwahr told me that this debate blazed like a comet across America's consciousness and then vanished just as quickly, out of sight and out of mind. Here's presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan speaking out against imperialism during his campaign in 1900.

William Jennings Bryan: We do not want the Filipinos for our citizens. They cannot, without danger to us, share in the government of our nation. Moreover, we cannot afford to add another race question to the race questions which we already have. Neither can we hold the Filipinos as subjects, even if we could benefit them by so doing, for such an inconsistency would paralyze our influence as the world's teacher in the science of government.

Daniel Immerwahr: The racial logic here is totally transparent. Interestingly, a lot of the anti-imperialism was a racist anti-imperialism. The objection to empire was that it would extend the borders of the United States in such a way that it would include more non-white people in the country.

Brooke Gladstone: Even during our transcontinental land grab, Americans shied away from taking land that was populated by people who were not white.

Daniel Immerwahr: Yes, it's really extraordinary. The United States expands a lot as the borders go west, but was always operating a logic of the United States should seek to take land, land that would then be used for white settlers, but it should not seek to incorporate large non-white populations. After the United States fights a war with Mexico in the 1840s, militarily it could seize a lot of Mexico, but politicians debate how much of Mexico does the United States really seek to annex.

The southern border of the United States was carefully drawn in order to give the United States as much of Mexico as it could get with as few Mexicans.

Brooke Gladstone: People of color cannot be trusted with the vote. That seems to be the governing principle here.

Daniel Immerwahr: That's the operative logic, yes.

Brooke Gladstone: Yet didn't we in the Navassa decision that recognized that our off-the-mainland holdings were still subject to American law, mean that the people who lived there had constitutional rights?

Daniel Immerwahr: You might think so. The Supreme Court has to figure out what to do with this newly shaped United States. There are a series of contentious Supreme Court cases starting in 1901 called the Insular cases. Ultimately, what the court decides is that constitutional rights apply in the mainland United States, but they don't apply in Puerto Rico. Shockingly, this is still law today. You can have rights in Puerto Rico, but they're not guaranteed by the Constitution because Puerto Rico exists in an extra-constitutional zone.

That's one reason also why if you're born in American Samoa, you're not a US citizen. You're born in the United States, but you're not born in the United States that's covered by the Constitution. The 14th Amendment doesn't apply to you and therefore you're a US national.

Brooke Gladstone: You're not a citizen?

Daniel Immerwahr: That's right. The history of the United States colonial empire is the history of a lot of people who are US Nationals and either are not US Citizens have to push to become US Citizens. Even when they receive that citizenship, for example, Puerto Ricans have been citizens since 1917, the citizenship that they receive is statutory i.e. it's provided by law, not by the Constitution, which also suggests that it can be taken away.

Brooke Gladstone: One of the most clarifying things that you do in your book is to describe the trilemma that placed the central ideas of what the United States is in conflict with each other when confronted with its imperialist role.

Daniel Immerwahr: That's right. In the late 1890s, when many people in the United States are contemplating the future of the country, they realize that they can have an empire. They can have a country that's ruled by white people and they can have a country that has representative government but they can't get all three of them.

Brooke Gladstone: Why not?

Daniel Immerwahr: Well, think about it, because now the United States includes large non-white populations. If the United States is going to continue to be Republican, Filipinos should have some kind of representative government and should have some kind of voice in the federal government of the United States. Those are the principles of republicanism. They're taxed, they should be represented. That seemed like it was a founding and core principle of the country.

There are a lot of anti-imperialists, including William Jennings Bryan, who worry about what happens to the United States if suddenly non-white people have political power. Some people try to solve this one way by allowing the expansion of the United States, but by rejecting its republican principles. That's how Teddy Roosevelt thinks the United States should grow. It should have republicanism for the mainland, but not for the entire country.

Others, like William Jennings Bryan, seek to resolve this by not having empire, by limiting the growth of the country so that it doesn't have the problem of large non-white populations who otherwise might need political representation.

Brooke Gladstone: There's a really loud debate about this.

Daniel Immerwahr: It's in some ways a tragic debate because those are usually the two positions you hear. The United States should abandon republicanism, or the United States should limit itself to its contiguous borders. What you don't hear in the mainland debate is the third option. The United States should jettison white supremacy.

Brooke Gladstone: They never considered taking white supremacy off the table, and yet they manage to reconcile these three incompatible ideas.

Daniel Immerwahr: Largely this happens by not talking a lot about the territories. If you can brush it under the rug, the United States can still present itself to itself and to others as a republic, the distinctive and exceptional world power without being an empire.

Brooke Gladstone: The maps of greater America start to go away.

Daniel Immerwahr: Literally, you can see the boxes erased. If you look at textbooks that are published by 1920, it is really hard to find a map that shows any part of the United States beyond the mainland.

Brooke Gladstone: In terms of press coverage, let's talk about the invisibility of the people that the US had come to rule first, statistically.

Daniel Immerwahr: The census is the statistical self-portrait of the nation. If you look at the census from 1910, from 1920, from 1930, the first page in the population report will say, this is the population of the United States, and here's the population of its possession. Everything after that in the census, how rural or urban is the population? How long do people live? What kind of jobs do they have? All these ways in which the United States seeks to understand itself, those calculations are implicitly just about the mainland.

The argument is that people who live in the territories are just too different to be included in the calculation. Essentially, they are relegated to the shadows.

Brooke Gladstone: They're invisible in our numbers, more or less. They're also invisible in American popular culture. I was struck by your discussion of the films about the Long March in Bataan.

Daniel Immerwahr: That's right. One of the more dramatic events In World War II is the Japanese conquest of the Philippines. This becomes the single bloodiest thing ever to happen on US soil. World War II in the Philippines ultimately kills 1.5 million people, about 1 million of whom are Filipinos or US nationals. That's two civil wars. There is very little registering of that on the mainland during the war. Frankly, there's very little registering of that now. It's not the kind of thing you find in textbooks.

During the war, the thing that you see most about on the mainland is these wars about a fight in the Bataan Peninsula where Filipino soldiers and soldiers from the mainland were making a last-ditch defense of the Philippines against Japan right before the archipelago got occupied and conquered. What's so interesting about these films is that they focus with laser-like intensity on the white soldiers.

Speaker 11: Our club on Bataan took another rap on the chin last night.

Daniel Immerwahr: The tragedy of the loss of the United States largest colony. A tragedy that will lead to the single bloodiest thing that ever happens in US history, this is entirely understood as something that happens to characters who were played like people like John Wayne.

Speaker 11: By then, the Air Force will have won the war, I suppose. Only, where is the Air Force?

Daniel Immerwahr: The Filipino presence is almost completely erased from the reception of World War II even when it's taking place in the Philippines.

Brooke Gladstone: Obviously if people are viewed as lesser and if they are invisible, they're more vulnerable. Tell me the story of Cornelius Rhoads, who was sent by the Rockefeller Institute to Puerto Rico to study anemia.

Daniel Immerwahr: Cornelius Rhoads, Harvard-trained doctor, arrives in Puerto Rico in the '30s. He regards Puerto Rico as a sort of island-sized laboratory. Here's what we know. First of all, he intentionally refuses to treat some of his patients just to see what will happen. He also seeks to induce diseases in others by restricting their diets. He describes some of them to his colleagues as experimental animals. He sits down and he writes to a colleague in Boston, one of the most extraordinary letters that I've read in US history. He says, "I am here in Puerto Rico. It's beautiful except for the Puerto Ricans."

Speaker 12: They are beyond doubt the dirtiest, laziest, most degenerate, and thievish race of men ever inhabiting this sphere. It makes you sick to inhabit the same island with them. They're even lower than Italians.

Daniel Immerwahr: "This island would be great. But if something could be done to exterminate the population."

Speaker 12: I have done my best to further the process of extermination by killing off 8 and transplanting cancer into several more. The latter has not resulted in any fatalities so far. The matter of consideration for the patient's welfare plays no role here.

Daniel Immerwahr: He leaves the letter out. It's discovered by the Puerto Rican staff. It seems to conflict all of the fears that Puerto Ricans have about mainlanders and it becomes a scandal on the island.

Brooke Gladstone: This letter helps to fuel the nationalist movement of Pedro Albizu Campos.

Daniel Immerwahr: That's right. There's already a small nationalist movement in the 1920s. Pedro Albizu Campos is at the head of it but in the 1930s, economic depression and then the issue of this letter turn it into a major force in Puerto Rican politics. Albizu passes this letter around to anyone who will listen. He sends it to the Vatican. The appointed colonial governor, who's a mainlander, describes it as a confession of murder. There's an investigation, and how that investigation plays out is really telling. First of all, Rhoads just leaves and there's an investigation without him. Rhoads' defenders say a few contradictory things. He was drunk, he was joking, he was angry, but the point is that he didn't actually kill eight people.

The government, which is staffed by appointed mainlanders, runs an investigation, finds another letter that is, as the governor sees it, worse than the first, which is hard to imagine. We don't know what that letter says because the government suppresses it, destroys it, and decides that Cornelius Rhoads was crazy and intemperate, but that he didn't actually kill people.

Brooke Gladstone: Maybe he was intemperate, maybe he was a little out of his mind. He paid the consequences by being appointed the vice president of the New York Academy of Medicine and in the army During World War II, Chief Medical Officer in the Chemical Warfare Service.

Daniel Immerwahr: Yes, and he goes on to have this illustrious career in medicine and basically suffers no consequences. Then in the army, in the Chemical Warfare Service, he gets another go.

Brooke Gladstone: Meaning he gets to use people as experimental animals again.

Daniel Immerwahr: Exactly right. The United States government is seeking to develop chemical weapons in case World War II becomes a gas war, which it never really does. Overall, some 60,000 people are tested on. Sometimes that looks like having a mustard agent applied to your skin to see what kinds of blistering happen. Sometimes it's men are put in gas chambers with gas masks and are gassed to see how well their gas masks hold up. The largest scale tests are these tests on this island that the United States seizes off of Panama.

Speaker 13: After a survey of the Southwest Pacific theater and the Caribbean area, San Jose island in the Pearls Group was selected as the test ground. Since the climate and flora are similar to that which has been found in the Southwest Pacific--

Daniel Immerwahr: It uses those to stage field tests. Large groups of men are asked to stage mock battles. While they're doing this, planes fly over and gas them from the air and then the question is, how well do the men hold up?

Brooke Gladstone: Where did these soldiers come from? Who are they?

Daniel Immerwahr: The government is unwilling to send continental troops to be used as test subjects in San Jose island in this way, so Puerto Rican troops come. Many of them don't speak good English. They don't really understand what's happening. The men who are gassed, 60,000 men who are gassed, they experience long-standing effects, many of them emphysema, scarring, lung damage. These men were also supposed to be doing this secretly, and it only really came out in the '90s just how many of its own people, and a good number of them Puerto Ricans, the United States had tested chemical weapons on.

Brooke Gladstone: Cornelius Rhoads becomes the head of the Sloan Kettering Institute and one of the forefathers of chemotherapy. This is a supremely surreal twist.

Daniel Immerwahr: Some of the mustard agents that work as poison gases also work selectively in fighting certain kinds of cancers. A number of doctors figure that out during the war. They put a pin in it, and they say, "After the war, let's check this out." The government makes available its stock of surplus chemical weapons.

Cornelius Rhoads is in charge of deciding which hospitals get it. He gives it to three hospitals, and a good bunch of it goes to his own hospital. Then he has a Sloan Kettering Institute, of which he's the head. Then he has for the rest of his career this incredible chance, a hospital that is full of dying cancer patients who will submit to experimental treatments. He just goes for it and just test chemical after chemical after chemical, and in doing so, becomes one of the forefathers of chemotherapy.

Presenter 1: Dr. Cornelius P. Rhoads of the Memorial Hospital in New York.

[applause]

Daniel Immerwahr: He's on the cover of Time Magazine, able to cultivate this image of himself as a cancer fighter without anyone really acknowledging that he's had this back history in Puerto Rico.

Brooke Gladstone: Most people didn't know the informational segregation is so complete.

Daniel Immerwahr: After Rhoads dies, there's an award that's given out by the American Association of Cancer Research in his honor for promising young cancer researchers. This award is given for over 20 years before anyone who's involved, who's in the medical community and has a voice in that way, can say, "You might want to rethink the name of this award," because powerful people in the United States, not just politicians, doctors too, have basically been able to think of their country as a contiguous blob and haven't really had to grapple with the parts of US History that have taken place in the territories.

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: Coming up, why understanding America's history of empire is vital for making sense of everything from bin Laden to the Beatles. This is On The Media.

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: This is On The Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. We end this rebroadcast of our hour with his historian, Daniel Immerwahr by probing the hidden ways the pursuit of empire has changed our history and especially for our purposes, our view of our history, because that blinkered view has allowed us to see past human rights violations committed on our own soil, here or elsewhere.

Jim Moran: The reason we have Guantanamo is that this was set up to be above the law. It's extrajudicial.

Brooke Gladstone: Former Virginia Congressman Jim Moran.

Jim Moran: The rules don't apply. The rest of the world looks at this, and it undermines our credibility and our security as a nation.

Brooke Gladstone: We have people born on American territory who aren't legally citizens.

Speaker 16: The people of American Samoa are considered US nationals.

Speaker 17: You're born owing allegiance to the United States, but you're not a citizen. America doesn't owe its allegiance back.

Brooke Gladstone: Of course, this.

Speaker 18: President Trump tweeting, "The people of Puerto Rico are great, but the politicians are incompetent or corrupt. Their government can't do anything right."

Brooke Gladstone: Even during the height of American empire, even During World War II, even among soldiers fighting in US territories, there was confusion about what exactly the status of those territories was.

Presenter 2: From the United States of America, Uncle Sam presents--

Brooke Gladstone: In your book, you recount the story of a young Filipino boy, Oscar, who encounters a GI coming down the street handing out cigarettes and Hershey bars. Speaking slowly, the GI asks the boy's name, and when he replies easily in English, the soldier was startled and he said, "How'd you learn American?"

Daniel Immerwahr: That story slays me because you have to think of it from the perspective of the soldier. first. He's crossed the Pacific. He's been given maps. He's been told where to go, whom to shoot. He's arrived in the Philippines. He's seen some of the bloodiest fighting of the war, and he meets this kid, and when the kid speaks in English, he's totally confused why this kid should speak in English.

When Oscar explains, "Oh, the reason I speak English is that after the Philippines became a US colony, you guys sent a bunch of teachers and we all learned to speak English." The soldier just looks at him and says, "Oh, I didn't realize that the Philippines was a US colony." He doesn't actually realize that he's fighting on US soil. We usually think of the war as catapulting the United States into the position of global leadership with a larger military, a more bustling economy than anywhere else.

Actually, the war did something else, too. It gave the United States a lot of territory so much territory that there were more people living in its colonies and occupied zones like Japan, than were actually living in the States. If you looked up at the end of 1945 and you saw a US flag flying overhead, it was more likely that you were living in a colony or occupied zone than you were actually living on the US Mainland.

Brooke Gladstone: Truman saying--

Truman: We do not seek for ourselves 1 inch of territory in any place in the world.

Brooke Gladstone: FDR said it, Everyone said it, but people are like, "We're going to keep Micronesia, right?" Suddenly our borders are malleable.

Daniel Immerwahr: It's a moment when the United States has the ability to decide what its territorial destiny will be. It could take a lot of that territory. It could convert its occupations into annexations if it wanted to. When Truman says the thing that so many past presidents had said, "We covet no territory," there's a scandal about that. The State Department complains, the military complains, the public complaints. "Are you really saying that we're going to give up all the land that we fought so hard to get, the places where we've planted our flag?"

They're particularly concerned about Micronesia, which is a sort of buffer zone between Japan and the western parts of the United States, including Hawaii. That's where a lot of the bloody fighting had happened in World War II. The idea of the United States surrendering this strategically valuable space, that's hard for a lot of people to countenance. In fact, Truman amends his statement.

Truman: Outside the right to establish necessary basis for our own protection, we look for nothing.

Daniel Immerwahr: We're going to keep what we need to preserve our security. In that moment, right after World War II, when the United States has so many options territorially, the end of World War II brings a worldwide revolt centered in Asia, against empire. Formerly colonized people have often seen their empires dislodged, often by Japan. They have access to arms. They've heard the idealistic speeches of FDR that this war is not a war for empire.

This is a war for liberation, which produces a sense of shame, which makes it a lot harder for powerful countries to insist that empire is right and proper. That's just how civilization goes without fearing the kind of real on the ground and possibly violent resistance that they'll face in the colonies. The cost of colonialism has gone up.

Brooke Gladstone: That's one of the trends. The other one is that there are new ways to project power worldwide without controlling vast swathes of territory. A lot of these are technological. We can now produce a kind of nitrogen-based fertilizer that replaces guano. We needed rubber and we developed fake rubber. We got plastic. Then basically all we really needed were military bases.

Daniel Immerwahr: That's exactly right. On the one hand, the United States figures out how to generate synthetic substitutes for a lot of things that had formerly depended on colonies for. Rubber is a really good example. At the start of the war, the United States has a rubber crisis.

Speaker 21: Well, Charlie, this is one of the last rubber tracks we'll get. That's right. If we don't get rubber, we'll have to stop making good tanks.

Daniel Immerwahr: The reason it has a rubber crisis is that Japan has seized a number of European and US colonies in Southeast Asia in rich rubber-growing lands. It looks to a lot of people like the US economy is just going to fall flat on its face because you can't fight a war, it turns out, without rubber. What happens, and this is a surprise to a number of people who live through this and are watching it, is that the United States figures out how to make rubber not from rubber plantations, but from petroleum, from oil, of which it has a great deal.

Suddenly it's done a sort of colonies for chemistry swap that it allows it to no longer depend for strategic reasons on tropical colonies. Rubber is one example. Plastic, which is also honed during the war, replaces any number of tropical products and allows the United States to be immune to the desire to colonize large places so that it can control, for strategic reasons, their economies.

Brooke Gladstone: We got radio to facilitate communications.

Daniel Immerwahr: It used to be the case that if you wanted to send a secure message from one part of the planet to another, you had to send it through a wire. If you wanted that to be secure from sabotage, interruption, or espionage, you had to control all of the territory along that wire. The British Empire was obsessed with getting a large telegraphic network that went only through British-controlled territories, so its adversaries couldn't snip its cables or listen in. The world of radio brings something different.

With radio, you can just control one transceiver in one spot, another in another spot, and beam the message from one to another. Now, people can still listen in, but if you get really good at encrypting your messages, you can solve that problem as well.

Speaker 22: Roger six able. They're between hills two niner zero and three two six, south of the--

Daniel Immerwahr: A similar another thing happens in transportation as you see a world that goes from surface-hugging transportation, such as steamships, cars, trucks, and railroads, to a world where ultimately, if you need to get something from point A to point B and you don't control the territory in between, you can transport it by plane. The United States gets really good at using plane and radio and it figures out that ultimately when push comes to shove, what it really needs is just a series of well-situated points all across the planet.

Brooke Gladstone: That's what you call a pointillist empire, which still endures today.

Daniel Immerwahr: Yes, it's important to recognize that although the United States has distanced itself from colonialism, it no longer has the Philippines. Hawaii and Alaska have become states. Puerto Rico underwent a constitutional change, although it's still very much a US territory. From a strategic perspective, that's not the core of the US Empire today. What the United States has is hundreds of overseas bases. Places where it can land, places where it can detain people, places where it can repair, and places where it can store weapons. That is really the face of power today for the United States.

If you took all US overseas territory today and mashed it all together, you would have a land area that's less than the size of Connecticut. They may be small, but oh boy, are they important.

Brooke Gladstone: A lot of history turns on those places and a lot of culture. A lot of Americans may not know this country's colonial history, but people in Puerto Rico do, people in the Philippines do, and so do people who live near those bases all over the world.

Daniel Immerwahr: One really good example is the city of Liverpool. Before World War II, it hadn't been a particularly culturally inventive city. Then after the war, suddenly it lights up like a Christmas tree and there's just band after band after band and you know, hundreds of them and they're playing rock music.

[MUSIC - Chuck Berry: Roll Over Beethoven]

Daniel Immerwahr: Suddenly it's a sort of world center. It's not all of Britain that's doing it. It's particularly Liverpool.

[MUSIC - Chuck Berry: Roll Over Beethoven]

Gonna write a little letter

Gonna mail it to my local DJ

Daniel Immerwahr: Liverpool has right outside of it the largest US base in all of Europe. As a result, Liverpool is this sort of borderlands between this outpost of the United States and a still very much impoverished and war-torn Europe. Young people from Liverpool and from the area recognize that the men on the base are a great source of cash. At the same time they're receiving records from them, they're getting musical instruments from them.

It's not an accident that the Beatles come from Liverpool. Liverpool is the contact zone between the United States and Western Europe.

Brooke Gladstone: It isn't all sunny in Japan. There's a deep sense of resentment. Riots every 10 years or so. Two Japanese ministers forced to resign because they deferred to the US in matters related to the base. Then the Saudi Arabian bases, one could say that they had a role to play in 9/11.

Daniel Immerwahr: That's right. Often in areas where bases are stationed people are drawn into them because they're sources of income but they often find themselves resenting the bases, understandably and you can see that so well in Saudi Arabia. After the war, the United States establishes a military base in a place that had already been a company town for a set of oil companies, Dharan. It has to build up this base. It draws on a lot of local laborers to do so. One guy who's been working on this base for a while is a Yemeni bricklayer named Muhammad and he's really good.

The people he's working for are very encouraging of him. He starts his own firm and starts to get a lot of contracts. The firm is called Muhammad and Abdullah Sons of Awad bin Laden. The guy who builds that Base and who builds some other US Bases is Osama bin Laden's father. Osama bin Laden grows up around US bases in the Middle East, US-sponsored construction projects in the Middle East. On the one hand, he's part of this. That's where his money comes from. He gets really into construction. He's a construction guy. On the other hand, he gets deeply resentful and regards it as a form of imperialism.

It's this basing issue, particularly as the United States puts more troops in a formally closed base in the 1990s, that sets Osama bin Laden on his jihad against the United States. It's the issue of US Troops being stationed in Saudi Arabia, the land of Mecca and Medina, turning, as Osama bin Laden regards it, turning Saudi Arabia into a US colony. That's his main source of complaint about the United States.

Brooke Gladstone: How do we know that?

Daniel Immerwahr: The first thing that we know Osama bin Laden did is a bombing at that base.

Speaker 23: An explosion occurred this afternoon at the United States military housing complex near Dharan, Saudi Arabia.

Daniel Immerwahr: Precisely the base that his father helped to build. That bombing is timed so it is the eighth anniversary of the stationing of US troops there. He's communicating through the date exactly the thing that he is protesting.

Speaker 23: The explosion appears to be the work of terrorists. If that is the case, like all Americans, I am outraged by it. The cowards who committed this murderous act must not go unpunished.

Daniel Immerwahr: I think that the United States has to get right on empire. For too long it's been so easy from the mainland to not think about the overseas parts of the United States, despite the fact that mainlanders have been consistently affected by them. The overseas parts of the United States have too often been sacrifice zones, places where the full cost is paid for decisions made in Washington, World War II in the Philippines. That's where most US nationals die in World War II, and many of them die from the US military itself, which bombs and shells its own cities as it's trying to dislodge the Japanese.

My point is not that military strategy was wrong, but my point is that it was made in a kind of bubble without any real reckoning of who it is that lives in the United States. I think that can't keep going on.

Brooke Gladstone: Daniel, thank you so much.

Daniel Immerwahr: Brooke, it's been a pleasure.

Brooke Gladstone: Daniel Immerwahr is a historian at Northwestern University and author of How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States.

[MUSIC - The Odd Man Who Sings About Poop, Puke, and Pee: A Nice Song About Bird Poop]

Bird poop, Bird poop

Birdie, birdie, birdie,

Poop, poop, poop,

Bird turd, turd from a bird

Turd it, turd it, turd it,

Birdie, birdie, birdie

Tweet, tweet, tweet, tweet goes birdie

Brooke Gladstone: That's the show On The Media is produced by Molly Rosen, Rebecca Clark-Callender, Candice Wang, and Katerina Barton. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer is Brendan Dalton. Eloise Blondiau is our senior producer, and our executive producer is Katya Rogers. On The Media is a production of WNYC Studios. Micah Loewinger will be back next week. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

[MUSIC - The Odd Man Who Sings About Poop, Puke, and Pee: A Nice Song About Bird Poop]

Birdie turd, birdie turd,

Poop, poop, poop,

Bird turd.

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.