[music sound effect]

TERRANCE MCKNIGHT: This is the Open Ears Project.

Ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five, four, three, two, one. Peter Piper picking pepper-pickles.

[MUSIC PLAYING: Perotin’s Viderunt Omnes]

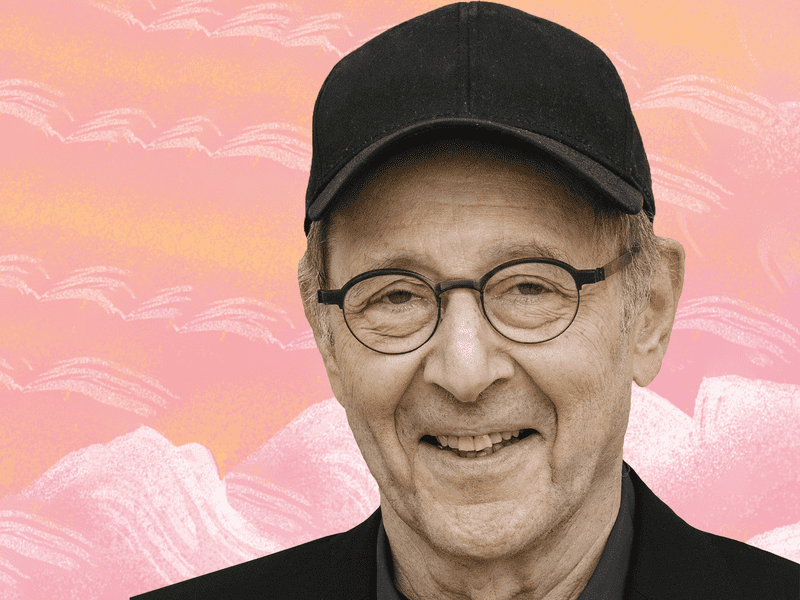

Steve Reich, here. I'm a composer. We're listening to Viderunt Omnes by Perotin written in the 12th century.

How did I first discover this music?

I was at Cornell, I think it was 1954 and I was studying music history with William Austin, and he played this gorgeous music and I didn't quite get the name of the composer and I-I, it would seem completely different than anything I'd ever heard before.

So he had a reserve shelf of books that we could find out what it was, and it was a book called Masterpieces of Music before 1750. And there was this little chunk of Perotin.

Now, Perotin, what kind of name is that? Some people say, well, maybe his name was Pierre. It was more like a title.

There's an anonymity to the whole thing, this entire organum, it's called, was discovered by an English man who named himself Anonymous 4 and brought this music in a kind of rotation which we can barely read, but it's another mentality.

People are working for the church. There's a religious sensibility there which is following rules, following traditions.

I mean, Perton is making enormous changes. He's writing the first four part music that we have… We now have soprano, alto, tenor bass. This is a big deal.

The music is written in this rather narrow compass. You don't have big expressive melodies, as you find in the romantic period, they're tighter.

Working within a fifth, you just, you would feel cramped-no, you feel like there's a certain tension there.

When you have a dam in front of a body of water, it's a very tense situation. But you can cut little holes in the dam and you have hydroelectric power.

The techniques of retrograde- playing something backwards - or inversion - when the music goes up, you go down, but you use the same intervals and the same notes - produces variation within a tight restricted area, which is nevertheless, it's been around forever.

Perotin actually doesn't deal with that directly, but he is working with Dee-Da-da dee-dee – basically, he’s in three. Nobody really had any measured rhythm before, too. So you had a series of rhythms and you could pick which one you wanted to use. You didn't invent them, you chose from the existing menu.

So it's a very different kind of innovation which he does through the use of this restricted menu. And I find that very, very, very attractive especially, but of course, but it's just beautiful music.

What’s happening that really is amazing is that there's these long held tones that are not drones because they are really part of a melody which is being augmented, made enormously long.

And then if you had a (sings) that for the could go on and I'm running out of breath (sings) while the other tenor picks it up. Meanwhile the other tenors are playing (sings) whatever they're doing.

So, this is an idea which has had an enormous effect on me. The most obvious piece is a piece I wrote in 1970, Four Organs, which is all about short chord gets long.

I wrote that in my music notebook - I woke up in the middle of the night: “short chord goes long,” back to bed. And then I spent several months working out the piece. It never would have happened if I hadn't heard Perotin.

I think also the kind of music that I do and that Riley has done and Phil Glass has done and many other people are doing.

One of the hallmarks of it is that the amount of harmonic change which is now growing, but originally was compressed. There were not so many changes of harmony and the changes happened further apart, what they call harmonic rhythm was very slow.

Perotin is the master of slow, enormously elongated harmonic rhythm. And there's no bass but the tenor becomes the anchor of the tone that you're going to be in.

So it's very, very markedly contemporary sounding but people find it attractive and they can, you know, they don't have to think about why but it's just beautiful music.

It's interesting that all this music does grow out of religious traditions. I'm a religious person… and I haven't written… I mean, I wrote Tehillim. Tehillim is the setting of the Psalms.

The church encourages and has commissioned enormous amounts of music for the mass and for other functions for the church where the music can be performed as part of the service.

In Jewish tradition, Synagogue is not that way at all. Basically, there's a man reading from the Torah in a chant and that's the only music that's there and the rest of the service is just, you know, without, without music.

There have been various changes in that, but the traditional way is that way.

So with Tehillim, it really belongs, you know, in Carnegie or Zankel or Lincoln Center or the kitchen.

So I think, in the case of Perotin, is it a religious piece of music? I would say, no, it's a piece of concert music written on a religious text.

Those are distinctions that are interesting. But the most important part is that this is in the air, this is in the air and people gravitate towards it.

Gravitating on, on musical magnetism. Magnetism is different. There are some people who say, “How can you listen to that?” And they mean it, you don't argue with that, you just, you know, make an observation.

I mean, you know, I don't really wanna sit through a lot of romantic music. Does that mean it's not good? No, certainly not. And that means, other people are, are also…. Ridiculous. Absurd.

We vary, you know, it's cliche but it's true.

[OPEN EARS THEME MUSIC: Philip Glass’s Piano Etude No. 2]

TERRANCE MCKNIGHT: That was composer Steve Reich sharing the music of the French medieval composer Perotin. Viderunt Omnes is coming up right after the break. Stay with us.

[MUSIC PLAYING: Perotin’s Viderunt Omnes]

TERRANCE MCKNIGHT: This is The Open Ears Project.

Join us next week. Martha Lane Fox is bringing us a little bit of Beethoven

MARTHA LANE FOX: Those kinds of moments when people say, oh, you are so brave or they’re generously kind about how I did it. But I don't think it's a choice. I think you either do it or you don't in those moments of extremis, and if you don't, you die and if you do, you don't.

TERRANCE MCKNIGHT: The Open Ears Project was conceived and created by Clemency Burton-Hill. I’m Terrance McKnight. I’m so pleased to present season two of this podcast to you.

If you like what you hear, please leave us a rating and a review on your favorite podcast platform. And if you’ve got a story about a piece of classical music, we want to know. Email us at openears@wqxr.org.

You can also head to our website, WQXR.org, to check out our other podcasts about classical music and playlists for this and past seasons.

Season two of The Open Ears Project was produced by Clemency Burton-Hill and Rosa Gollan. Our technical director is Sapir Rosenblatt, and our project manager is Natalia Ramirez. Elizabeth Nonemaker is the executive producer of podcasts at WQXR, and Ed Yim is our chief content officer.

I’m Terrance McKnight. Thanks for listening.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.