[music sound effect]

TERRANCE MCKNIGHT: This is the Open Ears Project.

[Harmonica]

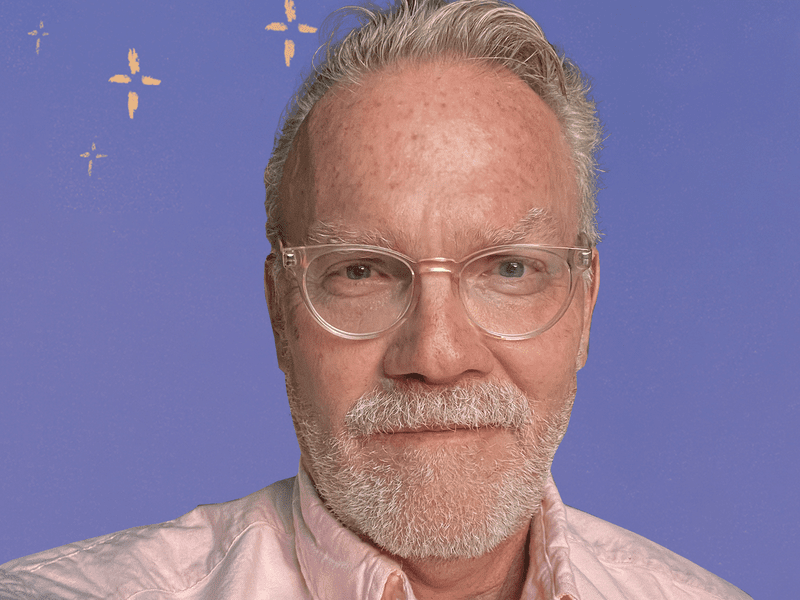

NICK FERRONE: My name is Nick Ferrone, I live in Brooklyn and by day, I'm a real estate agent, and by night, I'm a harmonica player. You can often find me playing at Sunny's in Red Hook on Saturday nights.

[MUSIC PLAYING: Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings]

I've chosen Samuel Barber's adagio for strings. It's a piece that I've always loved since I first heard it.

It was in Platoon back, I think, in 1986. I saw the film in Brooklyn. there was a theater on Flatbush, right off of Seventh Avenue, right above the Q train station… some people will know that.

And, I was really moved by that piece of music and I got it pretty much straight away and started listening to it.

The first few times I heard that piece, I thought, wow, this composer is so interesting. He actually added some voices near the crescendo. I swore there was, there was a chorus behind the strings.

It turns out it's either just the violas or it's an overtone, I-I still haven't figured it out. I still like to pretend I'm hearing those voices.

It's the pace. It's simple. The theme is pretty basic, it's sort of a stepping up and stepping down and the tempo is part of what makes it – it's very slow.

He also, he leads with the violins, but during the piece, sometimes the violas take the lead and sometimes the cellos take the lead, it sort of mixes in and out.

So the cellos are starting to take over. It almost becomes like a conversation between the string sections and when it resolves so well at the end of each phrase.

I'm the seventh of eight kids, so I benefited from having older brothers and sisters who are playing records that my friends weren't getting to hear.

So we were listening to the Grateful Dead and the Allman brothers and Joni Mitchell, James Taylor. I was like, what, 12 or 13 and I was listening to Wake of the Flood over and over again in our family library.

But then one of my brothers brought home an album called Giant Step by Taj Mahal and he plays harmonica on that album.

He's an amazing musician and kind of a hero of mine. He's great on all of his instruments, but I especially liked his harmonica playing.

So I've been playing harp since I was maybe 13 or 14 years old.

It's sort of an overused expression or term these days, But I'm a very ADD person. That's why I'm good at real estate. It's a good job for that kind of character.

But the harmonica is… as someone who's got ADD, I’ve tried a few times in my life to learn to play the piano, for instance, I love the piano, but there's just something about getting beyond those basic lessons that I just can't do… unless you experience it, it's hard to explain.

If you are studying a lesson, the ADD brain will want to just sort of see what those notes down there sound like and, “oh, that's interesting. Let's play over there.”

And all of a sudden you're not doing the lesson, you're just sort of fooling around and you never quite get over that hump of learning the instrument.

Harmonica, on the other hand, they're very simple. I often have one with me. I play a lot of harmonica in the car when I'm in traffic. It's a great way to practice and also remain calm among the frustrated drivers of New York.

You know, when I'm playing harmonica, I try to create something original and beautiful and Barber sort of hit on a formula of instruments and tempo and theme that just resonate with people. It just works. And I'm fascinated by the chemistry of it, I suppose. there's a technical part to it, but then you get past that and it's just a thing of beauty really.

And a lot of people say it's sad and it is. It was used after JFK's death, it was used after 911.

It's often considered a song of mourning. But I like to say it's more melancholy, sort of a thoughtful sadness.

And I also think it's a beautiful thing, so how can that be just sad?

you could be on a beautiful lake in the mountains and have it on your headphones and you could just splendor at nature with this incredible music in your head.

I-I think it's almost unfair to the music that it's been adopted as sort of a funereal piece.

Just in thinking about, what is it like when you go to a funeral? You sort of have this deep conversation with your friends and family about this person you've lost and it kind of crescendos at this very moving moment where you, you're thinking so much about this person and then you walk away and you're sort of conducting your own life again.

That said, I definitely tapped into it when my daughter was going to the hospital for open heart surgery. And I definitely remember listening to this piece when she was in the hospital and we weren't able to be with her all the time, that was pretty difficult.

She had a condition called a patent ductus, which umm, is usually pretty minor and typically they wait until a child is two or three to do this corrective surgery, but hers was so on the extreme end that she was essentially bleeding internally, the term is failure to thrive.

I remember, after the surgery, the first time we saw her, she was on an adult bed in the ICU with lots of tubes going in and out of her. And she looks so vulnerable and injured, but better. You know, she was operating normally and that was a relief.

She thankfully had a fairly minor thing to repair, but when she was four months old, that was pretty tough to handle and leaving your baby in the hospital overnight is not fun. So… I certainly remember listening to it then.

But this is where I don't find it to be a sad piece always. There's something so humanly connected about it, and I think that's why people respond to it so deeply.

It's, oh, gosh, it's, I-I don't know how it does it, how this music does it but, sort of the continuum of the human experience of just being a person here on this planet and surviving its ups and downs.

[Theme music]

TERRANCE MCKNIGHT: That was Nick Ferrone. He’s a real estate agent and harmonica player. You might’ve heard him refer to it as the “harp” – that’s a nickname that blues musicians often use for the harmonica. He was talking to us about Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings.” It’s coming up right after this break. Stay with us.

[MUSIC PLAYING: Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings]

[Theme music]

TERRANCE MCKNIGHT: This is The Open Ears Project.

Be sure to listen in next week. We’ve got composer, violinist, and vocalist Caroline Shaw joining us. Fun fact, Caroline and Kendrick Lamar are the youngest people ever to win the Pulitzer Prize in Music. They were both 30 years old when they got it. But before all that … she was just a kid at music camp, hearing the music of Felix Mendelssohn for the first time.

CAROLINE SHAW: The memory of being 15 is very much a part of this piece for me. [Laughs] I think it’s important for us all to have music that we remember from a time when maybe we had this sense that anything is possible, and, as we get older, the world becomes more complicated and there's more friction in the air. But, I think it's really important to remember that feeling of possibility.

TERRANCE MCKNIGHT: The Open Ears Project was conceived and created by Clemency Burton-Hill. I’m Terrance McKnight. I’m so pleased to present season two of this podcast to you.

If you like what you hear, please leave us a rating and a review on your favorite podcast platform. You can also head to our website, WQXR.org, to check out our other podcasts about classical music and playlists for this and past seasons.

This episode of The Open Ears Project was produced by Clemency Burton-Hill and Rosa Gollan. Our technical director is Sapir Rosenblatt, and our project manager is Natalia Ramirez. Elizabeth Nonemaker is the executive producer of podcasts at WQXR, and Ed Yim is our chief content officer.

I’m Terrance McKnight. Thanks for listening.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.