[sound effect]

TERRANCE MCKNIGHT: This is the Open Ears Project.

HANNAH ARIE-GAIFMAN: Art is always important. It's the freedom. Art, music, literature, that's the real freedom. That's where we find our real expression.

People often don't realize that this is the only thing that survives, ultimately.

[MUSIC PLAYING: Sarabande from Bach’s English Suite No. 5]

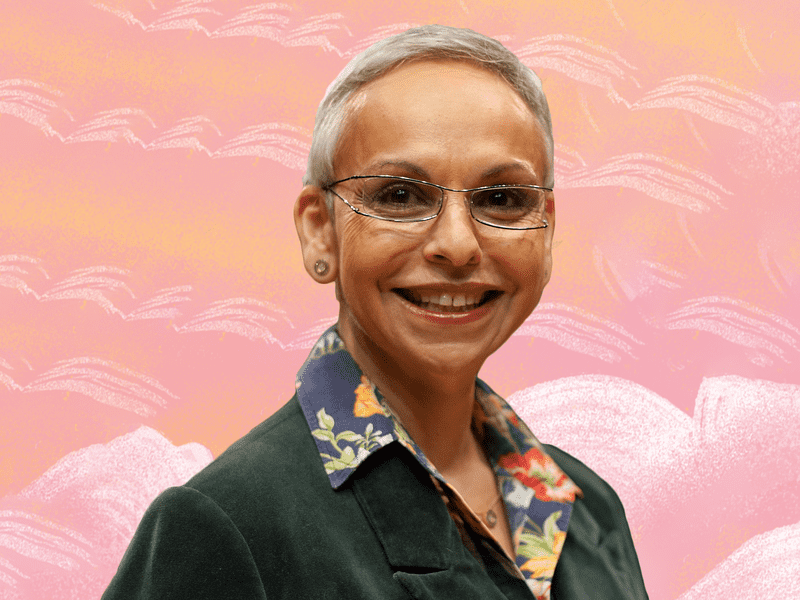

I'm Hannah Arie Geifman. I was the director of the Tisch Center for the Arts at 92nd Street Y in New York City. We are listening to the Sarabande from Bach's English Suite Number 5, which reminds me of my very beloved cousin, Zuzana Ruzickova. Holocaust survivor of Auschwitz, Terezin, Bergenbelsen, and my role model of my whole life. And this Sarabande accompanied her, her whole life.

Susanna, since I remember her, was both a great musician and never a self -pity person. At 14, she was called up for deportation to Terezin. She went to see her piano teacher, and that was apparently the last lesson she had with this teacher.

And they played the Saraband together as a duet. And she came home and transcribed it. She wrote down this Sarabande for herself from memory and held to this piece of paper of her transcription. She held this paper. When they were deported from Terezin to Auschwitz, she still had that paper.

And then she was to be sent on a truck to hard labor. And she's on the truck and drops the paper. Her mother was supposed to stay behind. And she saw that she was going to be sent on a truck. after it and caught it and ran after the truck.

And the women helped her to get on the truck. And they stayed together. The guard didn't pull her down. And in that way, the Saraband kept them together.

[MUSIC PLAYING: Sarabande from Bach’s English Suite No. 5]

Auschwitz and everything that came after was much worse because she very quickly learned what was happening.

She had to be... 16 in order to be sent for hard labor. She was just 15 when she arrived in Auschwitz. And somebody told her, "Don't give them your right age. Say you're two years older, otherwise they'll send you to gas immediately." So that saved her. And had she not had that information, she would be gone.

Towards the end, she actually told me that in Bergenbelsen she was praying to be sent into a gas chamber because they were making people dig big holes and threw the prisoners into those holes and they're pouring gasoline over them to burn them. So for her, it was like, to die in a gas chamber would have been a relief. Luckily, they got liberated in time.

But I know that by then, this Sarabande was so deeply inscribed in her mind, heart, ears, everything that the paper, as symbolic as it was, was not an absolute necessity.

She used to sing it for herself to keep structure to her life. And Bach in general was the point of reference of meaning and structure in life.

I had her playing it, the Sarabande. I must have been eight, nine.

[MUSIC PLAYING: Sarabande from Bach’s English Suite No. 5 on harpsichord]

And then I went home and learned it. When I feel I'm confused or things are getting really difficult, the Saraband is the go-to piece. It's always there. It doesn't know time boundaries, no limits, just beauty. Absolute beauty.

There's nothing pretentious about it. And at the same time there is so much and you can listen to it, no end, and there are so many layers and so much. It doesn't pretend to be complicated or sophisticated and at the same time it has it all and it has a solution, even musically you have a solution there.

Susanna was much older than me. We would spend hours and hours in conversation about music, about literature, about her life. But I didn't know the whole story at that time.

I loved her, but I knew relatively little about her difficulties. I knew she survived, I knew it was horribly difficult. Coming back from all the camps being told to never play a piano or anything else again.

She overcame all these challenges and in 1956 won the Munich competition and became one of the great harpsichord players of her generation.

But she basically won her battle against the limitations through her music, through the quality of her music. And she told me when her father was dying in Theresienstadt, he said, "Don't hate. Hate poisons your soul. Leave revenge to God."

And she lived that way. She really found joy, whether it was a good piece of food, cake, a nice walk, her absolute love of nature, and we would take walks in Southern Bohemia, go swimming together. She had her joy of music making, her joy of teaching, and she was never tired. She said, "How can you be tired if you play Bach?"

She died in 2017, just a few months after her 90th birthday. And she claimed that the biggest accomplishment was that she lived 90 years. I think the way Susanna absorbed music, expressed music, she had something to say through music. And there was nothing that could stop her.

It's the miracle of survival and the miracle of music.

TERRANCE MCKNIGHT: That was Hanna Arie-Gaifman, sharing a story about the Sarabande from Bach’s English Suite No. 5. Stay with us. After the break, we’re going to play you a version performed by Hanna’s cousin, the acclaimed harpsichordist, Zuzana Ruzickova.

[MUSIC PLAYING: Sarabande from Bach’s English Suite No. 5 on harpsichord]

TERRANCE MCKNIGHT: This is The Open Ears Project.

Folks, this season of The Open Ears Project is coming to a close. I want to extend a huge thank you from the whole show team for listening and following us. Thanks to everybody who’s left ratings and reviews — it really does help the show — and thanks so much to the folks that have written in to share their stories about the pieces of classical music that have meant a lot to them. Be sure to follow WQXR on Facebook and Instagram, where we’ve been sharing excerpts from some of those stories. And if you’ve been thinking about reaching out, there’s still time! You can email us at openears@WQXR.org. We’d love to hear from you.

But we’re not done with the season just yet. Next week we’re going to be joined by cosmologist Janna Levin. She’s talking space, science …. And Mozart.

JANNA LEVIN: It's a piece that's always appealed to me both for its extreme ambition and loftiness, but also the sort of bittersweet fact that it was never finished.

I find that that resonates with my impression of what life will ultimately always be like: the striving for something absolutely unattainable and that it will never be finished.

TERRANCE: Season two of The Open Ears Project was produced by Clemency Burton-Hill and Rosa Gollan. Our technical director is Sapir Rosenblatt, and our project manager is Natalia Ramirez. Elizabeth Nonemaker is the executive producer of podcasts at WQXR, and Ed Yim is our chief content officer.

I’m Terrance McKnight. Thanks for listening.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.