Garth Greenwell on Finding Refuge in the Music of Britten and Pears

[Sound effect]

Terrance McKnight: This is the Open Ears Project

Garth Greenwell: When I hear these opening chords

[MUSIC PLAYING: Britten’s Before Life and After from Winter Words Op. 52]

I'm in the bedroom of my house in Louisville, Kentucky. I'm 14 years old. I'm listening on my headphones and I'm feeling like... what this music shows me is real life, a life that I feel determined to find somewhere in the world.

My name is Garth Greenwell. I'm an American novelist and I've chosen music by the 20th century English composer, Benjamin Britten.

I grew up in a household that was not very engaged with the arts. I was first generation raised off the farm in Kentucky. The tobacco farm was still very much part of our lives. The rhythms of the farm felt like my life. At the same time, my father... it was so important to him that he had escaped that world.

My father had a very brutal childhood. He wouldn't talk about it often. I know that it was dirt poor. I know that he lived exposed to violence. It was crucial to him that he had become something that felt to him bigger than his childhood.

He was the first person in his family to go to college. He became an attorney and then he wanted to flaunt that, and part of flaunting that was the fact that his children had not grown up on the farm. It was so important to him that we sounded different. I remember, after the summers when my brother and sister and I would come back and we would have country accents because we had been hanging out with our cousins. And the rage my father would feel when he heard us say “ain't”.

There was a kind of ferocity I didn't understand, and the only time I heard my father's childhood voice, his accent, was when he was enraged. It was actually how I knew he was enraged, because he would speak with his country voice, not with the sort of refined voice he had adopted through his education.

[MUSIC PLAYING: Britten’s Prologue from The Turn of the Screw]

SUNG: “It is a curious story. I have it written in faded ink…”

Garth Greenwell: I became aware of music because in a public high school in Kentucky, the choir teacher heard something in my voice and started giving me voice lessons after school for free. And, um, when I met him, my father had just discovered I was gay and kicked me out of the house and disowned me.

SUNG: “... a young man, bold, offhand and gay… the children’s only relative”

Garth Greenwell: And he was the first adult to treat me as though my life might have value. His name is David Brown and he was the first person to show me opera.

SUNG: “...The children were in the country…”

Garth Greenwell: He gave me art, he gave me opera videos, he gave me tickets to the Kentucky Opera. The second opera I saw was the Turn of the Screw by Britten, and it blew me away.

SUNG FROM SONG PROLOGUE: “...but there was the girl and the holidays now begun…”

Garth Greenwell: I had an experience of feeling that the world was so much bigger than I had thought it could. It felt to me like the opposite of Kentucky, but it also felt to me like a world where I might have a place, and it was very clear to me that in the world of my childhood, I did no.

SUNG: “...always something, no time at all for the poor little things…”

Garth Greenwell: I became obsessed with Benjamin Britten. Um, I became obsessed with his music and I became obsessed with his life and the fact that he was gay and the fact that in a world that was bitterly repressive, in which homosexuality was punished by incarceration, or worse, he created a space in the world in which he could publicly celebrate his lifelong love for the tenor Peter Pears.

[MUSIC PLAYING: Britten’s The Choirmaster’s Burial from Winter Words Op. 52]

SUNG FROM THE CHOIRMASTER’S BURIAL: “But t’was said that, when

At the dead of next night, The vicar looked out, There struck on his ken…”

Garth Greenwell: Discovering their relationship, discovering their story was extraordinary for me. Their bravery, but also their innovativeness, the way that they managed to sort of force the world into letting them live more openly than the world thought they had any right to live.

I remember, I mean, I really just…. I bought every CD I could buy. Um, I read every book about Britten I could find.

SUNG: “Singing and playing…”

Garth Greenwell: Listening to the recordings between him and Peter Pears was for me really… My first experience of the possibility of queer love.

And then in Britten's own music… I think Britten's music is really the most astonishing act of love I know.

SUNG: “Such the tenor man told, When he had grown old.”

Garth Greenwell: Peter Pears has a voice that is not the kind of voice that is usually praised in opera. He often sings a little under the pitch. He has a wobble. It sounds strained. Britten's music is, to me, the ideal act of love because what it does, it constructs a world in which what seems like flaws become sources of beauty.

Britten's music is a world in which his beloved is beautiful, and so you hear how the world he makes doesn't just accommodate, doesn't just set off in a way that makes it shine, but also does something more. You know, when you listen to Pears sing it, you hear music that is at once accommodating his limitations and also challenging him beyond them.

[MUSIC PLAYING: Britten’s Before Life and After from Winter Words Op. 52]

SUNG: “A time there was—as one may guess, And as, indeed, earth’s testimonies tell…”

Garth Greenwell: This is a song called “Before Life and After”. It's the last movement of the cycle, Winter Words, in which Britten sets poems by Thomas Hardy.

SUNG: “...When all went well.”

Garth Greenwell: There's an exquisite, glorious duet between the tenor and the melodic line in the piano. I think one reason I wanted to listen to this song again and again and again is because it does sound to me like a love song, even though there's only one voice, but the piano is a voice and it's so beautifully counterpointed.

SUNG: “None cared whatever crash or cross”

Garth Greenwell: The poem by Thomas Hardy is a fascinating poem. It's an extremely dark poem. It's the poem of someone longing not to be. It's someone who is suffering great pain, wanting to be made incapable of suffering, pain.

SUNG: “If something winced and waned…”

Garth Greenwell: And then in that last stanza, something happens. We're no longer in a single harmonic universe, the feeling is that the ground has fallen out from beneath us. The line is: “Ere nescience shall be reaffirmed… How long, how long?”

This profound utterance of longing for this negative thing and yet, what happens in the music… what happens in Pears' voice and in the vocal line, where somehow this statement of utter negation… has the sound to me of affirmation.

SUNG: “Ere nescience shall be reaffirmed… How long…”

GG: As Pears sings, how long, how long, how long

SUNG: “How long, how long, how long…”

Garth Greenwell: That's what I hear in Pears' voice. That's what I hear in the remarkable changes the song undergoes. So that what is actually, I think, a poem in Hardy, of despondency, becomes something much richer, much stranger. Something that to me, as a 14 year old in Kentucky, convinced me that I could live.

[MUSIC PLAYING: Britten’s Before Life and After from Winter Words Op. 52]

Garth Greenwell: My father found out I was gay because my stepmother opened a letter. I was the kind of kid who had pen pals because I didn't have friends. I had just begun to realize that I was queer, or I had just begun to put that into words. And to one of these pen pals I wrote something along those lines: “I think I might be gay.”

When my stepmother finally decided to push that to its crisis. My father was out of town, he was in New York on a business trip. My stepmother and I, for a totally unrelated reason, had a big fight and she kicked me outta the house and told me to go to my mother's house. And so I called my father and I said, tell her to let me back into the house.

And he said, if what you say about yourself is true, you're not welcome in my house. Which are words that I will never forget, or the sound of his voice saying them, which was the sound of his childhood and the last thing I said to my father, which was the last thing I would say to him for years, was: “but I'm your son.”

And he said, in that country voice: “the hell you are.”

And he said, “if I had known you were going to be a faggot, you would never have been born.”

[MUSIC PLAYING: Britten’s Before Life and After from Winter Words Op. 52]

To turn from that sound to this sound, to the sound of Pears and Britten.

This music and indeed this song, which I remember listening to again and again and again and again… was something that allowed me to survive.

SUNG: “Before the birth of consciousness when all went well. None suffered sickness, love, or loss. None knew regret…”

[OPEN EARS THEME MUSIC: Philip Glass’s Piano Etude No. 2]

Terrance McKnight: Writer Garth Greenwell on vocal music by Benjamin Britten as performed by Britten’s partner Peter Pears. We heard a few pieces in that episode, including selections from the song cycle “Winter Words” and the prologue to “The Turn of the Screw.”

Stay with us. We’ll be playing “Before Life and After,” which is the last movement from “Winter Words,” just after this break.

Terrance McKnight: This is The Open Ears Project.

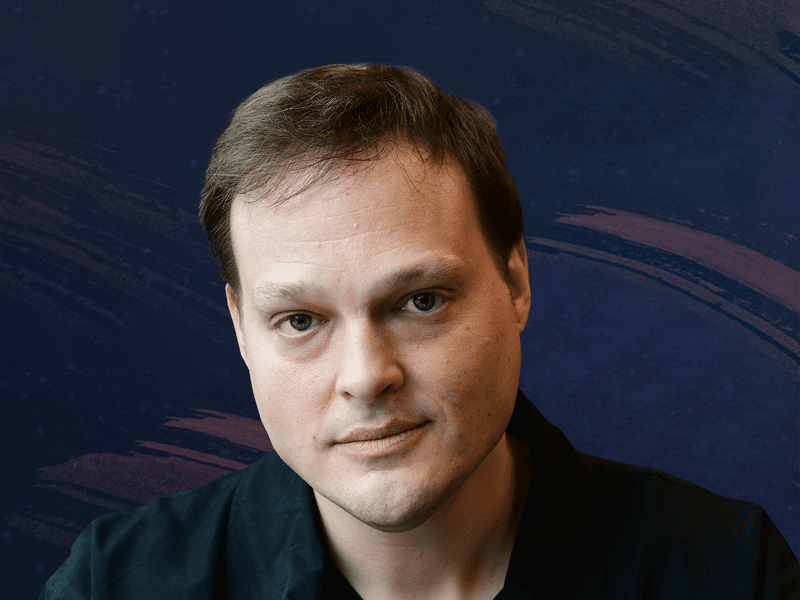

Pianist Víkingur Ólafsson is our guest for next week’s episode. He’s gonna talk to us about Rameau.

Víkingur Ólafsson: So this is the piece that sort of changed my, my life a little bit.

And it led me to, you know, much later now to really go into this kind of Rameau period where I just basically learned more or less every single piece that he wrote for the keyboard. I mean, nothing in the world sounds like this music.

Terrance McKnight: The Open Ears project was conceived and created by Clemency Burton Hill. I’m Terrance McKnight and I'm so pleased to present season two of this podcast to you.

If you like what you hear, please leave us a rating and a review on your favorite podcast platform and, if you’ve got a story about a piece of classical music, we want to know. Email us at openears@wqxr.org. You can also head to our website, wqxr.org, to check out our other podcasts about classical music and playlists for this and past seasons.

Season two of The Open Ears Project was produced by Clemency Burton-Hill and Rosa Gollan. Our technical director is Sapir Rosenblatt, and our project manager is Natalia Ramirez. Elizabeth Nonemaker is the executive producer of podcasts at WQXR, and Ed Yim is our chief content officer. I’m Terrance McKnight. Thanks so much for listening.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.