Your Brain On Sound

( Mary Harris / WNYC )

MARY HARRIS: When she looks back, Rose says she can see these little clues… that she she wasn't hearing the world the way other people were.

ROSE: When I was six or seven years old I started noticing a pattern…

MH: She’d hear her name being called.

ROSE: Usually my mom or dad, for the first time in like a, you know, like a yelling “Aghhh! Where are you?” And I’d say “I’m right here.”

MH: And she’d look up, surprised that they were shouting at her. They’d been calling and calling, but Rose would only “hear” that last, exasperated yell. Her parents joked about it. They called it “selective hearing”. But it was a big enough problem that every year or two, they would take her for a hearing test.

ROSE: I’d be in a booth, I’d have the headphones on...

MH: She’d ace them — every time.

ROSE: I’d have to like press a button when I heard a tone…

(tone)

ROSE: Yup, I heard that…

ROSE: I’d always hear things at past an average level, you know, I had healthy ears.

MH: It was the mystery of Rose’s childhood. The tests said she could hear. But Rose knew she couldn’t.

I’m Mary Harris and this is Only Human. A show about how our bodies work, and what happens when they do things we can’t explain, and send us on a search for answers.

A quick warning here at the top — this episode mentions a sex act.

I should tell you: Rose isn’t her real name. Because this problem: it’s been hard. Sure, she could pass those tests in a quiet doctor’s office. But in the real world, Rose missed things. And if you put her in a noisy place, even if it was just a little noisy -- it was almost like she heard too much.

Say, she was in a classroom: she heard the buzz of electricity, and the hum of an air conditioner, and the sound of kids whispering. The noises all piled up, one on top of the other. And they drowned out whatever she was trying to pay attention to. Other times, she says it was like she was cut off from sound by an imaginary wall.

For most of her childhood, Rose handled her hearing problem the only way she knew how: she tried to ignore it. But when she got to high school —

ROSE: I started to feel like something was wrong. I knew I was happy and strong and smart and all these things, but there was something that was different. In certain situations I couldn’t keep up.

MH: So she developed workarounds.

ROSE: People get frustrated when you say “what” a lot. And I started being sensitive to that, and I had this rule, I called it my ‘max what.”

MH: That’s the maximum number of times she’d let herself ask “what?” in a conversation.

ROSE: And it just started dwindling down, like it went from 4 to 2. And after so many “what’s” and if I still didn’t hear, I’d just take a stab at it.

MH: So you would go into a conversation and you’d get to four “what’s” or two “what’s,” and then what?

ROSE: And then I would take a chance and either smile and nod, or shake my head. Because I didn’t realize the extent that I was listening through all of these other signals. Body language, facial expression, hand movements. Like I was doing that all along, so I was most often right when I took a chance on my reaction. And people would look at me and kind of continue with the conversation, and I knew I had reacted sufficiently, or something.

MH: Was there a time where it was like, “Oh, that didn’t work.”

ROSE: Yes. I was I was 17 or 18, I was actually traveling, I was in Australia and I was with family. I was at this restaurant that also had a dance floor, a night club, and this guy asked me to dance. He kept leaning in, you know, just talking to me, and I just kept smiling and nodding

MH: Remember--it’s the middle of a dance floor. It’s noisy. Rose couldn’t hear much of anything.

ROSE: And I guess I agreed to something I did not really agree to because then he kind of took led me to back of bar, and when I pulled back and asked “where are we going?”

MH: He made a really crude gesture. The universal sign for a blowjob. And Rose freaked out.

ROSE: I could see he was offended and confused and that’s when I realized this could be dangerous. And then it was just like – “No more ‘what’s,’ no more smiling and nodding. Let’s figure this out.”

MH: That was when Rose decided: she had to figure out why her world seemed to sound so different than everyone else’s. She went to see a neurologist, and that doctor began to suspect Rose’s problem wasn’t with her ears — it was with her brain.

That’s how Rose...

NINA KRAUS: I’m Nina, Nina Kraus

MH: ...Found Nina Kraus. Kraus runs a lab at Northwestern University.

NINA KRAUS: The auditory neuroscience lab is where I do science.

MH: She specializes in how the brain perceives sound. She’s nicknamed this place the Brain Volts Lab.

NINA KRAUS: This is all about sound being this fabulous and invisible yet very powerful force.

MH: And let me just set the scene here, because if you had a favorite professor in college, it would probably be someone a lot like Nina Kraus. She has a Grateful Dead sticker on her office door. She bikes to work, even in the Chicago winters. And she loves playing the electric guitar.

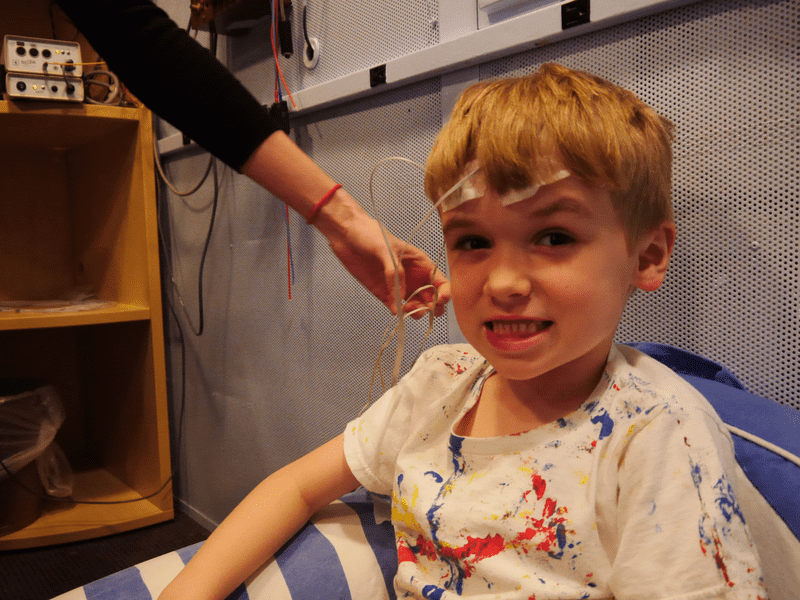

In her lab, Kraus uses EEGs — electroencephalograms — to study how the brain responds to sound. And to really tell you what was happening with Rose, I need to explain how this test works. So, I asked Kraus to give me one.

One of her lab assistants sticks electrodes to my head with a special glue

LAB ASSISTANT: I’m also going to be putting electrodes on your right and left earlobes – so we’re creating a circuit.

MH: And stuffs my ears with earbuds that play a series of tones. Those electrodes record my brain activity. It looks like a lot of squiggles moving across a computer screen. A technician in a separate room watches as these peaks and valleys scroll by...

LAB ASST: Then we average that together and you can actually see her brain response emerge as the background activity sort of washes out in the averaging process. It’s nerdy, but I kind of find it peaceful, to like see the waves emerge.

MH: These waves are the proof that our brains are listening. Think of the neurons firing in your brain like an audience clapping.

It’s a chaos of signals responding to all kinds of sensory inputs. But when you hear a sound, neurons in in the brain begin to clap in unison. It’s called neural synchrony.

And that’s what this test is measuring: the speed and accuracy of the brain’s response to sound. This clapping happens within microseconds of a sound being heard — and as cells fire in unison, waves appear on the EEG.

These waves — it turns out they look an awful lot like sound waves. Which is how Kraus and some colleagues got an idea: Could they could play an EEG waveform over a speaker? And what would it sound like?

They found that when a normal brain — a brain like mine — processes sound, that EEG I’m getting sounds like the audio I’m listening to.

That’s a hard idea to get the hang of, so here’s an example.

Say I was listening to a simple scale.

(scale)

MH: The EEG of my brain would sound like this…

(scale)

MH: Yeah, you heard that right. These are the sounds of actual brain waves, from actual test subjects in Kraus’s lab. That fuzzy noise you hear is the crackle of neural activity in the background. And this happens whether you’re listening to Mozart… or “Smoke on the Water”...

And that brings us back to Rose. Her brain waves would have sounded like this.

(static)

MH: Rose didn’t have neural synchrony — remember, that’s the super-fast brain cell coordination that this EEG is looking for. Rose remembers how confusing it was to hear that news:

ROSE: The results to that test came out completely different than what a normal functioning person’s results should be. They came back continuously as if I’d been in a car accident or born severely autistic, or… like it just didn’t make sense.

MH: Actually, this test showed that Rose’s brain looked deaf. Her condition didn’t have a name yet. But Kraus had seen it before.

When we come back: How Rose helped Kraus understand something new the brain. And how Kraus helped Rose understand herself. This is Only Human.

--

MH: Hey, and thanks for listening to the show. If this is your first time hearing Only Human, go back and check out our earlier episodes. We’d love to hear what you think. Leave a comment for us at onlyhuman.org, or find us on Facebook and Twitter. We’re @OnlyHuman.

Also, if you haven’t yet, subscribe to the show! You can do that in iTunes, or wherever you get your podcasts. And while you’re there, think about leaving a review. It helps other people find us.

--

MH: I’m Mary Harris and this is Only Human. I’ve been telling the story of Rose, who was a teenager when a test showed that her brain’s response to sound was almost entirely absent. It was a kind of brain deafness. Her ears could hear sound, but, most of the time, her brain couldn’t make sense of it.

Nina Kraus, the researcher who spotted Rose’s problem, had seen it before.

NINA KRAUS: We had called these kids “these kids.” “Oh, we saw another one of ‘those kids’ because there wasn’t a diagnosis. When I said “those kids” we knew we were talking about somebody who had normal hearing thresholds and not very measurable brain responses.

MH: “Those kids” were rare. Kraus would come across them just once or twice a year. And they often had other diagnoses: They had behavior problems, or Attention Deficit Disorders, or learning disabilities. But they’d found their way to Kraus because all of them were deaf in noise. When they were somewhere quiet, they might be able to hear well. But in a noisy place, hearing became all but impossible. Rose was different: being deaf in noise was her only symptom, so she was a perfect subject for Kraus. She became almost a partner in her research.

NINA KRAUS: Really I was learning as much from her as her from me.

MH: Rose told Kraus that understanding the world around her took a huge amount of effort —

ROSE: Because if I hear it that’s one step. But then I have to like process it.

NINA KRAUS: She said how fatiguing it is to be making sense of sound, or trying to make sense of sound.

MH: Rose helped Kraus understand this: neural synchrony is the key to actually making sense of everything we hear. And that’s important for people with all kinds of problems.

NINA: You know, when people have concussions, when we get older, we have difficulty hearing in noise. And we really rely on this neural synchrony, we really rely on the brain’s ability to make these fine, fast timing computations.

MH: Nina Kraus also thinks that poor neural synchrony could be a kind of early warning system.

LAB ASST: Do you remember wearing the buttons from last year?

PARKER: Yes.

MH: That’s one of Kraus’s assistants. And Parker.

LAB ASST: Do they feel funny?

PARKER: Yeah they feel funny. Ooh it started. I think it’s starting.

MH: These days, Kraus’s lab spends a lot of time testing kids like him.

LAB ASST: Do you remember where the next two buttons go?

PARKER: You’re going to put them on this ear.

MH: Parker’s part of a sample of children Kraus will follow for years. He’s getting that same EEG test Kraus did on Rose, and on me. Kraus wants to see if she can predict how the kids’ brains will function as they get older. The test measures how the children process not just clicks and tones, but syllables and word fragments.

(DA DA DA DA DA… )

MH: The kids will listen to these sounds over and over again, so Kraus can get an accurate picture of how their brains respond. She’s found that differences in the way we process sound can be a marker for problems that seem to have nothing to do with hearing. Take, for instance, people with autism.

NINA KRAUS: A child or a person on the autism spectrum, typically does not have difficulty understanding what words were said - what the difficulty is, is understanding how do you mean it.

MH: Kraus’s test shows that some autistic children don’t encode pitch well. And that’s important because your tone of voice carries a lot of information.

NINA KRAUS: Am I mad? Am I sad? Am I asking a question?

MH: Kraus sees other kinds of processing differences in other people she’s studied. Just this summer, she published research showing she could actually predict which children would develop reading disorders simply by analyzing their EEGs when they’re preschoolers. Kids with reading difficulties often have brain cells that don’t fire in sync.

It’s actually a less extreme version of what Rose had.

MH: Hi nice to meet you.

ROSE: Nice to meet you, welcome!

MH: Thanks for having me over...

MH: I met Rose recently in her stylish townhouse in Chicago. Everything here is picture perfect, including Rose herself, in a crisp white shirt and black trousers. You’d never guess she’s keeping a secret about how she hears the world. Though, she has a name for her disorder now — Auditory Neuropathy.

Rose is 42 now, and two decades after her diagnosis, she still has trouble making out what’s going on around her.

MH: When do you tell people about it, or do you tell people about it?

ROSE: I don’t. It’s only when I get close to someone that it’s even mentioned -you - good friend, after being friends for a while will say like, “You have a hearing problem right - are you deaf in the left ear or right ear?”

MH: Do you feel at peace with it?

ROSE: No I don’t. I’m always on my toes with my ears, you know? And if someone kind and interesting is engaging me in conversation, I’m not relaxed, ever. And I lose a part of myself because I’m really myself when I’m relaxed.

MH: At work, she relies on the same coping mechanisms she used in high school. She takes lots of notes. Instead of making phone calls, she uses email and texts. Her close friends know she misses things in conversation, and they’ve learned to fill in the gaps.

Rose says even her preschool aged daughter, who was trying on princess outfits during my visit, knows she has to help her mom.

ROSE: When we’re upstairs playing and the downstairs phone — the landline rings — she knows at this point. She’s already becoming my ears - I’m like “Thank you babe.” She knows that she needs to tell me - or that someone’s at the door. If I’m playing with her and I’m focused on her, someone could call all they want, and I would not hear it.

MH: You can hear that Rose sounds wistful. She tells me about a daydream she has. It’s about something completely mundane: She just wants to be able to walk down a busy street with a friend and… talk. And then she tells me: “I’m lucky I can hear so well. I just wish I could hear well.”

This is the final episode in our series of stories about hearing, listening and understanding. We kicked it off by partnering with the Mimi app, which lets you test your hearing using an iPhone. More than four thousand of you took the test. And for most of you, this was the first time as an adult that you checked your hearing.

Zach, a linguistics grad student from Chicago, wrote to say that he took the test because he’s “interested not just in spoken languages but sign languages, too. It’s important for me to be able to hear and see what I’m investigating,” he said.

Rudi from Manhattan was diagnosed with nerve damage in both ears when he was 19. He wrote to say, “I’m 39 years old, and according to this test I have the hearing of someone between the ages of 58 and 63.” He calls his hearing loss “a struggle.” “If you want my undivided attention,” he says, “sit on my left. If I’m in a car with the window open, radio on and conversation between more than two people, I’m out.”

And Ruth from Ann Arbor told us, “I found closing my eyes helps me hear better. Maybe I should do that more often.”

You can get in touch with Only Human on Facebook and Twitter. We’re at onlyhuman. And we’d love to hear your feedback on this show and any of our earlier episodes.

Only Human is a production of WNYC Studios. This piece was edited by Molly Messick. Our team is Amanda Aronczyk, Paige Cowett, Elaine Chen, Kenny Malone, Fred Mogul, and Kathryn Tam. Our technical director is Michael Raphael. Our executive producer is Leital Molad. Special thanks to Lena Walker and Winn Periyasamy. Jim Schachter is the Vice President for news at WNYC.

And I’m Mary Harris. Talk to you soon.