Too Ornery to Die

( Mike Hill / Getty )

Julia Longoria: Rob?

Rob de la Noval: Hey!

JL: Hey! How you doing?

Mary Harris: This is our producer Julia Longoria. She’s talking to Rob de La Noval, a friend of hers from high school.

JL: So we’re going to talk about a lot of things. In like this direct way we would only do over several beers. But I want to talk to you because you’re like the starting point for this story we’ve been working on. And I’ve been thinking about the last time that you were in New York.

RD: Yeah, I think it was two years ago.

JL: So my friend Rob was visiting from Indiana. He’s actually a grad student at Notre Dame. And the plan was he was going to be here for a week. Have Pizza. Catch up about life. We hadn’t seen each other for a while

MH: Do all the New York things.

JL: Exactly. And things didn’t go as planned.

RD: The day that I got there, I began coughing up copious amounts of blood that evening.

JL: This isn’t the first time this has happened.

RD: I knew when it was coming.

JL: He always talks about like there’s this faucet of blood.

RD: I felt like ohp, the faucet’s been opened, and I could feel the blood rising up my throat and I knew I have to get out of wherever I am and get to a toilet because I’m about to cough up a ton of blood.

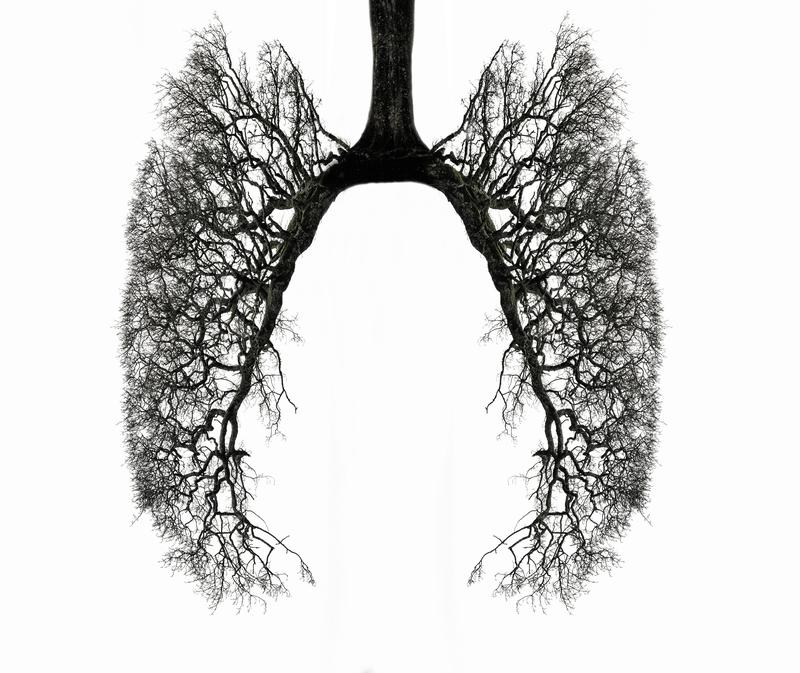

JL: So we rushed to the hospital. Growing up, this would happen every four months, like clockwork. Because Rob has this disease called cystic fibrosis -- he was born with it.

RD: The problem with us who have CF is that we don’t produce mucus at the right consistency. It’s extremely attractive to the ladies

JL: His mucus is thicker and stickier than our mucus. It’s almost like an Elmer’s glue consistency.

RD: And this ends up clogging our lungs or our other organs which eventually leads to all kinds of complications.

JL: And when he coughs up blood, it’s kind of like this sign that something got complicated.

RD: I mean at that point I recognized you know, the vacation’s probably over.

JL: And I didn’t know it then, because this was so routine while we were growing up. But Rob, when we were sitting there in that hospital, he was thinking this was the beginning of the end for him.

RD: You know growing up I really expected to lead a short life. Hmm, I expected probably to die in my 30s.

JL: So he thought he was dying. You have to understand the effect cystic fibrosis has had on Rob’s life. He’s studying theology at Notre Dame, where he thinks a lot about those big questions we all avoid.

RD: What’s the meaning of life? What’s the meaning of my life? Why was I created?

JL: Those life or death questions…

RD: Why do people suffer? Why am I suffering?

JL: Rob leans in to them.

RD: What about the fact that I already know people with CF who died before me. Why am I still alive? CF’s not as bad as leukemia. Why am I complaining in the first place?

JL: But in the last year… Rob’s thinking has totally changed. Because for the first time in his life, he’s getting better.

RD: I haven’t coughed up blood in an entire year. Of any kind. And that is just basically unbelievable.

JL: He’s on this new kind of drug, that treats the root cause of cystic fibrosis.

RD: And I think now I have to change how I think, and I think a lot about, okay, maybe you can chill out a little bit. Maybe you can take...

JL: That’s amazing.

RD: Maybe you can take on some projects that might take ten years. You know. Think about that. You know. And that’s a new and weird thought.

Or you know who knows, I could be hospitalized tomorrow and then this will just take on new degrees of irony. But hmm, but as of yet - that’s a side effect of CF right there, that kind of mentality.

JL: Historically, a rare genetic disease like CF just wouldn’t get a breakthrough therapy like this. There are so few people who have it, and for years, the science just wasn’t there. So this drug is a huge deal.

(( MUSIC ))

MH: So Julia came to us with this story of an amazing drug that has changed her friend’s life. In a lot of ways, this drug is the first of its kind. It’s proof that we can precisely target rare genetic defects, like Rob’s, and fix them. But when we started looking into it, we found some of the key scientists behind this drug had serious problems with how it got made.

Today on Only Human, we’re going to tell you the story of Rob’s new drug, from start to finish. Because this drug is being called a model for the future of medicine -- it could change things for all of us: who gets treated, for what, and at what cost.

((music fades))

One of the loudest voices against this drug is a researcher named Paul Quinton.

MH: Hi, is this Professor Quinton?

Paul Quinton: Yes, it is.

MH: Hi, it’s Mary….((fades))

MH: Which is surprising, because he made some of the key discoveries that made this drug possible. Before Paul came along, scientists didn’t have any idea what caused this disease.

PQ: Well I’m about as old as cystic fibrosis in fact.

MH: Paul was born in 1944, around the time the CF first patient was diagnosed. He’s been so dedicated to this disease because he has cystic fibrosis.

MH: What’s the average life expectancy for cystic fibrosis?

PQ: Now it’s about 41 or 42, something on the order of 40 years.

MH: How old are you?

PQ: I’m almost 72. So I have - most of my life I have been twice as old as I was supposed to be. So….

MH: Why do you think you've lasted as long as you have?

PQ: Well, my mother used to say it was because I’m too damned ornery to die. [laughing] But, she might be right.

MH: Growing up, his family just knew that he coughed a lot. So his mom would slather him with Vick’s Vapor rub

PQ: And sent me off to school if I wasn’t too sick, smelling like what I called a eucalyptus tree.

MH: And there was this one other weird thing… that turned out to be the tell-tale sign for cystic fibrosis.

PQ: I grew up in east Texas - southeast Texas - and we have lots of hot weather and big mosquitoes. And when I would sweat and the sweat would dry it would leave salt stains on my my clothes. So that was considered to be kind of unusual and interesting, but nobody made a big deal out of it.

MH: But when he started coughing up blood, he knew it was something serious. So as a college sophomore, he started to investigate.

PQ: So I went to the university library and started reading about it. And I noticed a footnote, that said, “see with reference to cystic fibrosis.” I came away with the rather stark conclusion that this disease fit me pretty well.

MH: The doctors confirmed the diagnosis with what’s called a sweat test. And Paul dedicated his life to understanding what was going wrong in his body.

PQ: My curiosity was set to see if I could figure out what the problem in cystic fibrosis is.

MH: If you’re looking for the root problem of CF, it makes sense to look at the lungs because most patients die of lung failure. But Paul kept wondering why the one thing every cystic fibrosis patient had in common was that salty sweat.

PQ: We decided after some futzing around for several years to look at the sweat glands directly.

MH: He actually carved out samples of his own sweat glands to study.

PQ: And the reason we did that is because the other organs of the body are really kind of, if you will, torn up. They’re wrecked by the disease. And so I decided that we should try to do it on the sweat glands because sweat glands had - were not destroyed. They just produced this high concentration of salt in the sweat.

MH: And sure enough, he found a problem. It has to do with how we move salt in and out of our bodies. All cells have these doors on them. They let molecules flow in and out. When we sweat, we release salt molecules and then absorb them back into the body using those doors.

PQ: In cystic fibrosis, that door is not working properly and so you can't get the salt back in.

MH: This was huge. Because salt molecules are really important. In other parts of the body, they help loosen mucus. In CF patients, that doesn’t happen. The mucus just builds up inside them, especially in the lungs. And then their organs gradually start shutting down.

PQ: And so that way we knew now what the basic problem was, at least at the cellular level. It wasn't the whole, whole thing by any means but it was an insight.

(( MUSIC ))

MH: Paul’s discovery meant scientists were able to trace the origins of cystic fibrosis to one faulty gene.

So in just fifty years, this disease went from not even having a name to being incredibly well understood, at the molecular level.

And that meant, for the first time - there was this hope.

PQ: There might be a compound or a drug out there that you could put on cells that have this defect and correct it.

MH: This approach is called precision medicine. Coming up with personalized treatment based on a patient’s genetics.

PQ: If that were possible then what we should do is look at as many compounds as we can.

(( MUSIC CONTINUES))

MH: To understand what happened next, we have to leave the lab for a minute and talk about how drugs get made in this country. Because finding a new treatment isn’t just about science - it’s about business.

And with cystic fibrosis, there’s a problem. It is really rare. It mostly affects Caucasians. Only 70,000 people have it, worldwide.

That’s a really small market.

So how can developing a drug for this tiny population make financial sense?

Barry Werth: Well, at the time no one really thought that it did.

MH: This is Barry Werth. He’s a journalist who followed the development of this cystic fibrosis drug from inside the company that makes it, Vertex pharmaceuticals.

He says with a disease this rare, a drug company would never think to take it on -- not by themselves --

BW: So you need an agency or a group that is so committed to an indiv disease that they are willing to put everything on the line for that disease.

MH: Enter the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation - a charity.

They decided to create an unusual partnership with Vertex, using money they’d raised as a non-profit to fund the very for-profit search for a new kind of drug. Barry Werth says it makes sense --

BW: -- that the people who are most passionate and most concerned and most in touch with the damage that the disease has done, are the ones who come up with the original seed money.

MH: In all, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation gave Vertex more than 120 million dollars. It’s called “venture philanthropy.”

And it paid off. After 15 years of searching, Vertex found a drug that worked in the lab. So they wanted to try it out on patients.

BW: And the question really was if you're twenty-five years-old or thirty years-old. And if you suddenly introduce an activating agent, would it actually work the way it was supposed to or would the body have done some kind of work around on its own or - you know what it. Well. It worked

People who had struggled all their lives to breathe better suddenly felt they had more breath, more stamina. They started to see they were developing fewer and fewer infections. They didn’t have to go to the hospital nearly as much.

((MUSIC))

MH: The FDA called it a breakthrough therapy -- this first drug was approved two years ago.

BW: Everybody was ecstatic. I remember going to a CF national meeting in Anaheim, California.

MH: He saw the president of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, a guy named Robert Beall --

BW: And Bob Beall, who is a very kind of stern and dour character came out dancing to James Brown’s “I Feel Good.”

MH: It wasn’t just a scientific marvel, it proved that pharmaceutical companies could do business in a whole new way.

And then…

Vertex announced how much it would cost. Researcher Paul Quinton still remembers when he read the list price. About 300,000 dollars a year.

PQ: And yes I was - I was stunned.

MH: Why.

PQ: Well wouldn't you be stunned if someone told you that you were going to have to take a drug that cost three hundred thousand dollars a year for the rest of your life. I mean how many times can you sell your house.

MH: Well, some people might hear this interview and think: Why shouldn't a drug like this be expensive it took a lot of work to make it a reality?

PQ: Um. If you have cystic fibrosis, do you think it should be expensive, more expensive than you can afford? So that you have to live with the contingency that you may not be able to have the drug. Or that you may have to lose everything you've got in order to get it.

MH: We tried to find out if the high cost of this drug is keeping patients from getting it here in the US. Three girls in Arkansas did have to sue Medicaid to get their treatment paid for. That was two years ago. Most insurance companies seem to be paying. They usually negotiate a discount on that list price.

MH: But in practice, aren't most most patients getting it from their insurers?

PQ: Probably most patients are, but now we've - we're entering into a new era here of what's called precision medicine. And this system is not sustainable because all of us have some kind of a disease or we're going to wind up with some kind of disease is going to need medication. And if those -- if those medications are priced like this, the system can't sustain it.

And it's not a drug that cures you it's a drug that you have to continue to - to to take and so there's a whole host of, of work and monies that were put into understanding the disease so that we could have a drug.

And all of these people are ... I think I can speak for.. probably all of them are so astounded that our work has led to a drug that has been priced so high.

MH: After conducting years of research that lead to this drug, Paul Quinton and a handful of other scientists say they felt betrayed. They didn’t keep quiet about it.

PQ: We had lunch with the CEO and we expressed our concern over how high the price was and his response was that, “Well it has to be that high because we have to recoup our investment.”

MH: Well, what do you say I mean you're also saying they're eating salads or whatever...

PQ: Yeah, at his expense. [laughs]

We said that we were stunned by this price, and we didn't understand why it had to be that high. And… we have constantly asked for transparency and how is this money spent, what is it going for. At that meeting, there was agreement that they were going to give us some kind of a statement as - to explain all this but it never happened. What did happen was that we were admonished not to give Vertex a difficult time by complaining too much because it would drive their stock prices down.

And that if their stock prices went down, they would be at risk of a takeover. And if they were taken over by another company, we would lose the only company that was going to develop a drug to cure cystic fibrosis

MH: But you... I mean okay, but let me just say... You bled for this. Literally. You took your own biopsy of your own skin. And the guy is saying, “Just wait, we’ll get back to you.”

PQ: Yeah. We're going to fix you for good.

MH: We called Vertex. They wouldn’t talk on tape. But they said 83% of their revenues go right back into research. And that research is paying off. They’ve released a second cystic fibrosis drug. Now almost half of all CF patients are eligible for these targeted therapies, and Vertex is working on more.

PQ: No, you know it is a difficult position. It really is ...I've had friends tell me that they would shake hands with the devil, if it meant that we would get a cure for this disease.

MH: Part of what makes Paul Quinton so uncomfortable is that these drugs wouldn’t have been possible without support from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. And that foundation has benefitted from this astronomical price tag. At the end of last year, they cashed out their investment in Vertex and made 3.3 BILLION dollars.

After the break, who has responsibility to keep drugs like this one affordable? And if pricey personalized medicine is the future, what does that mean for the rest of us?

*******************************************

** MIDROLL **

MH: Paul Quinton had to come to terms with his body -- and its limitations -- a long time ago. But even if you don’t have a chronic disease, I’m sure you’ve had that kind of moment. An injury that stopped you from running. Maybe your body changing after pregnancy. Or maybe it was way before that.

Lionel Shriver: I think my body betrayed me as soon as I went through puberty.

MH: That’s the writer Lionel Shriver. She spent her North Carolina childhood chasing after her brothers...and chafing against femininity. She was born Margaret Ann. But she never felt the name fit.

LS: I just didn’t think that was my name, I didn’t know how else to say it.

By the time I was 8 years old, I tried to change my name to Tony. T-O-N-Y, not I. So that was my first male pseudonym.

MH: And at 15, she permanently changed her name to Lionel. As for her body, she did learn to accept it.

LS: I’ve resigned myself, that I was born female. I’m not going to spend my life fighting having been female. I think that would’ve been a waste of my energies.

MH: Next month, we’re doing a show all about not feeling at home in our own skin. And we want to hear your stories: when did your body betray you - and how did you learn to live with it? Tell us about it. Call us and leave a message at 803-820-WNYC. That’s 803-820-9692. Or find us on Facebook - we’re at Only Human podcast.

************************************************

MH: This is Only Human. I’m Mary Harris.

Five years before these new cystic fibrosis drugs hit the market, patients were doubting they would ever get a treatment.

Francis Collins: And this is a song about CF and a song about the hopes that we all have.

MH: That’s when Dr. Francis Collins, who discovered the gene for this disease, got in front of the crowd at a meeting of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation… with his guitar.

FC: *Strum guitar* So uh let me teach you this.

MH: He is not a professional musician. He’s the director of the National Institutes of Health. The NIH is the largest public funder of biomedical research in the world. But at this meeting, he seems more like a camp counselor, convincing the crowd to sing along.

FC: *Strum* Dare to dream. Dare to dream. All our brothers and sisters breathing free.

MH: He was in a room full of the Foundation supporters… families and patients and scientists.

Can you describe that moment for me and what's going on?

FC: I do remember feeling like, not only do we have a group here of people who are intellectually committed to this. They are personally committed to this and there are families in the room as well who came to that meeting to hear what the latest science was. And so I wrote that song called, “Dare to Dream,” about what we were all doing, we were daring to dream of a day when cystic fibrosis would be written about in the history books.

MH: It’s Dr. Collins’s job to think about the big picture: What research gets funded? What diseases take priority? I asked him if he felt like the CF Foundation made the wrong call… by collecting 3.3. Billion dollars on an investment made by some of the folks in that room.

Do you see a conflict of interest here?

FC: I think it was actually a pretty creative scheme. Originally the CF foundation seeing that there was a need and recognizing that few companies, if any, were going to plunge in and take this on, they decided to make a deal to try to get them to work on it.

MH: He says the deal is done, and now the foundation has money to reinvest in the disease.

FC: I think that puts them in a pretty good position actually now not to be in a conflict of interest, where they can advocate -- and I hope they are -- for this drug to be widely available at an affordable cost.

MH: But The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation wouldn’t speak to us on tape. In a statement they told us the royalties they made are being plowed directly back into their mission to find a cure for CF. But they wouldn’t break down how they’re spending their windfall or whether they’re pushing for drug costs to come down.

The relationship seems very tangled.

FC: Well, I suppose you could look at it as tangled or you could look at it as, this is a desperate situation where people are dying of a terrible disease and you've got to be creative.

I think the bottom line is people with cystic fibrosis have a lot more hope -- and a lot more of a future --than they did before this very bold, and rather unprecedented initiative got underway.

MH: But if venture philanthropy is the future of drug development, do you ever worry about who decides what diseases will get treated in which won't?

FC: Yeah, I do worry a lot about that and I think people who look at the CF Foundation example and say, “Well, we can do that too,” have not really appreciated just how unique this one might have been. I don't know of any other rare disease foundation that had quite the same level of funding available, to put into this risky endeavor.

MH: But you know when I think of this though and, I keep thinking of, sickle cell anemia because it shares a lot with cystic fibrosis: it's a disease that's rare, and it's genetic, and it shortens life spans. But it's also a disease of primarily black people and CF is a disease that affects white people. It just doesn't feel like a coincidence. It feels like there's this privilege at work. And I don't know how you prevent that.

FC: Yeah, Mary, I'm deeply troubled about that as well. Sickle cell disease does have about the same frequency. The amount of research that's gone into that in terms of private foundation support compared to CF is really very small. The government has funded sickle cell disease research, but without that special push that the CF Foundation has provided.

And again as much as I also deeply regret that we're not working as hard on every other disease as we are on cystic fibrosis, I'm really glad the cystic fibrosis has made progress, and we shouldn't in any way say, “Well that was a bad thing,” they did some amazing work.

MH: I can hear in your voice you are such an optimist.

FC: I am. [laughs]

MH: But there’s still this price tag. And even Francis Collins calls those 300,000 dollars daunting.

FC: Well, it's certainly not something that the NIH that I now direct has the right levers to pull to change. That really comes down to kind of a negotiation between those who are going to pay the bills, which largely these days is health insurance companies or the government through Medicare and Medicaid, and the companies that make the drug that basically set the price not on the basis necessarily of what it cost them to develop the drug but what they think the market will bear.

(( MUSIC ))

MH: This is the problem. Negotiations in the U.S. for price are different from anywhere else in the world. Barry Werth, who followed Vertex for so many years, describes it really well.

BW: The government cannot -- because of terms negotiated by the drug makers -- bargain over price in this country.

MH: In the UK, the government has refused to pay full price for Vertex’s latest CF drug. They say it’s just not cost effective.

BW: The United States has the highest drug prices in the world, and other countries can negotiate on price. So that we in effect subsidize the rest of the world.

MH: But as drug companies find more treatments that rely on expensive precision medicine, this will get tricky.

BW: People have not thought this all through. This is our free market system marching on as it always does. And this is the result.

MH: What’s the solution here though?

BW: I don’t think anyone’s given this a lot of thought, unfortunately.

MH: Really? No one.

BW: Have you found anyone?

MH: No, I thought you were the guy.

Meanwhile, Paul Quinton has started taking the very drugs whose price tag he finds so outrageous. He says it’s making him feel better, and his insurance foots most of the bill. But --

PQ: I’m not sure I’m worth 330,000 dollars a year to society.

MH: Well I guess, you're a patient taking the drug, and you're a researcher who needs funding from places like the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. So how do you protest what happened here?

PQ: I'm not, I'm not sure that I'm protesting. What I would rather say is that I’m really questioning. And it's it's - I think this is something that really changes the course this is a new prec--. This is a precedent for a nonprofit organization because now, this is what I guess is called venture philanthropy, but it’s mixed with venture capitalism. And so as I look at this. I think on the one hand that. You know it's terrific that we have all this money that we can probably pursue. But on the other hand I think in so doing that, we have to be very very careful about how that — how that's treated. And I think it demands the ultimate in transparency, which is a lot of responsibility for a foundation that's nonprofit and altruistic.

((MUSIC))

MH: This whole story started with our producer’s good friend Rob.

Rob: If you have to have a disease, CF is not a bad one to be born with right now.

MH: He told her that now, this handicap he’s always had - that’s totally shaped his life - suddenly feels like this strange kind of ...privilege.

JL: When you saw that price, what was going through your mind. Were you worried about access?

RD: I was worried about access. I worry more about it now a sense. I worry what would happen if it went away?

MH: He feels really vulnerable. Rob gets his drugs through Medicaid.

RD: Because the standard and the quality of life has changed so much for me that it’s almost hard to imagine going back now to the hospitalizations, worrying again about this. That I wonder you know what happens if lawmakers decide, “You know what? This is too expensive.” And I understand too but this gets at some very serious questions about who we are as an American society.

MH: Rob is 27 years old now. And he anticipates taking these drugs for the rest of his life. He’s hoping that will be a very long time.

--

Only Human is a production of WNYC Studios. This episode was produced by Julia Longoria.

Our team includes Elaine Chen, Paige Cowett, Jillian Weinberger, Kenny Malone, Fred Mogul, Ariana Tobin, Ankita Rao, and Amanda Aronczyk. Our technical director is Michael Raphael. Our executive producer is Leital Molad.

Special thanks to Megan Cunnane and Eleni Murphy.

Jim Schachter is the Vice President for news at WNYC.

I’m Mary Harris. Talk to you next week.