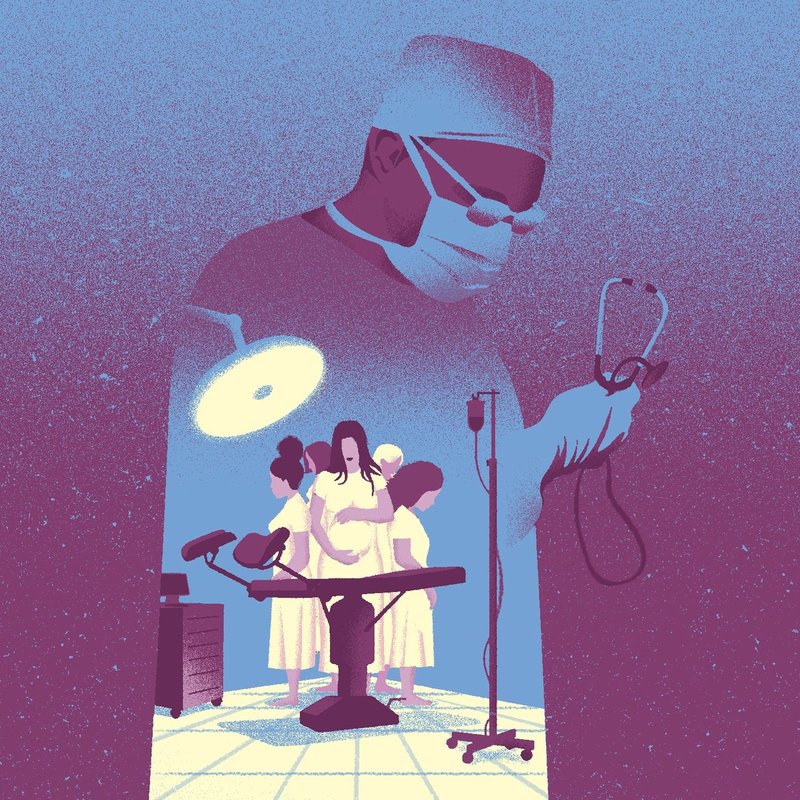

Imminent Danger Ep 3: One Doctor and a Trail of Injured Women

Janae Pierre: Good morning. It's Saturday, October 21st. Welcome to NYC NOW. I'm Janae Pierre. Every Saturday for the last few weeks, we've been releasing a new episode of our five-part series called Imminent Danger: One Doctor and a Trail of Injured Women. Produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center. Today, we have the third episode. If you haven't checked out the first two, we highly suggest you do that. Here's Christopher Werth, the investigative editor at WNYC and Gothamist.

Christopher Werth: Previously on Imminent Danger, we heard how an OB-GYN named Thomas Byrne lost his medical license in New York in the early '90s after being found negligent by state authorities.

Speaker 5: I remember saying to the nurses who were there, my peers, saying, "Do you all understand that this did not have to happen? This was preventable?"

Speaker 6: If you're a physician and lose your license, nobody wants you. The lawyers will say, "We don't want the liability of dealing with someone who was a physician and lost their license."

Christopher Werth: In this episode, The Gatekeepers. Our reporter, Karen Shakerdge, takes a close look at what happened after Byrne left New York to continue practicing in other states, New Mexico, and then Oklahoma, where more malpractice suits were filed against him. Just a heads up, this episode includes a detailed description of medical injuries. Here's Karen.

Karen Shakerdge: As part of my attempt to learn more about Dr. Thomas Byrne, I've reached out to all kinds of people, ex-wives, former colleagues, office assistants, doctors who spoke out about him decades ago. I've also tried to track down every single patient who filed a lawsuit against him, 23 cases, claims that span from 1989 to 2021, because every time I talked to someone who knew him or interacted with him, I learned something more, something new that gives me some insight into how Byrne has continued practicing. There was one patient in particular, Marquita Baird, who helped me start to see a pattern forming. She got back to me right away when I reached out, the day my letter arrived at her house.

Marquita Baird: Oh, I stood up and went, "Yes."

Karen Shakerdge: Even though it has been more than 20 years since Dr. Byrne did surgery on Marquita, it was almost like she'd been waiting for someone to call her up and ask, "What happened that day in 1999?"

Marquita Baird: I don't want to see this happen to a young woman who's got the rest of her life to have been able to enjoy. I'm doing this for the benefit of female humanity, I guess.

Karen Shakerdge: Marquita lives in a small city in Oklahoma called Shawnee. It's about an hour's drive from Oklahoma City, surrounded by open fields, casinos, churches, and reservations. About six years after New York took away Byrne's medical license, he started practicing there at a rural hospital nearby called Seminole Medical Center. Marquita has kept records in a boot box up on the top shelf of a closet in her guest room, 590 pages, doctor's notes, court records, detailed nurse logs. What I'm about to tell you is based on those documents.

Marquita Baird: I held on to these records all this time. I always knew somebody somewhere was going to get in touch with me someday because of what he did to me.

Karen Shakerdge: The whole thing started back when Marquita was 37 years old. She went to see Dr. Byrne because she had something called polycystic ovarian syndrome.

Marquita Baird: My ovaries and fallopian tubes were just covered in cysts. I did not intend to have any more children, ever. The only answer they had was to do a hysterectomy.

Karen Shakerdge: Dr. Byrne removed her uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries, and he kept pretty detailed notes including that he was "concerned about injury to the bladder or ureters," but he also noted that her urine eventually cleared up and was totally normal. Ureters, by the way, are the tubes that carry urine from the kidneys to the bladder. Three days after the surgery, he discharged Marquita.

In her records, he wrote, "There were no operative complications." She went back to the hospital the very next day. Her medical records say her abdominal wall was swelling, and by her account, a lot.

Marquita Baird: Everything was swollen. I was in so much pain and bleeding, and I couldn't pee.

Karen Shakerdge: About two weeks after the surgery, she went back to the hospital again and still couldn't urinate. Byrne noted she had gained 18 pounds in just 11 days. What was going through your head?

Marquita Baird: I had absolutely no idea what he had done to me. I expected a hysterectomy, but I did not expect my stomach to be pooched out like I was nine months pregnant. Yes, I did, I looked like I was nine months pregnant.

Karen Shakerdge: Eventually, Marquita saw another doctor, a urologist at another hospital who determined what was wrong. According to her medical records, one of her ureters and bladder were injured.

Marquita Baird: I was, quite frankly, peeing into my stomach.

Karen Shakerdge: Over the next six months, Marquita would need to have a series of medical procedures. She had stents put in to help urine make it into her bladder. She says the whole experience took a serious toll on her.

Marquita Baird: The constant back and forth, having to have the minor surgeries, it was a ordeal.

Karen Shakerdge: Marquita sued Dr. Byrne and the hospital, Seminole Medical Center. She claimed that Dr. Byrne negligently performed the hysterectomy on her. Five more women would sue him for procedures he did while he practiced at Seminole and at another hospital close by. This was work he did in a span of just four years, including one patient who alleged that after doing a hysterectomy, he left a foreign object inside of her body, which caused her severe injuries.

That case settled but the others were dismissed. Byrne eventually left the area and started working at another hospital a few hours away. Marquita's attorneys dropped the case because she and her husband, at the time, hadn't filed their taxes for several years and they didn't think that would look good in front of a jury. As she sees it, justice was never served.

Marquita Baird: With every inch of my being, I would like to see this man's-- if he is trying to practice, be dismissed forever. Just take his license away from him and don't let him practice anywhere.

Karen Shakerdge: That last thing Marquita said about not letting him practice, that's actually something that all the former patients and family members I've spoken with, more than a dozen people, have communicated to me in one way or another, that somebody needs to stop him. The only entity that has the power to give or take away a doctor's license is a state medical board. There are actually 70 of them in the country, by the way. Some states have two, one for physicians with MDs and one for osteopaths.

The boards are the traffic cops standing at the intersection of which doctors can come and which have to go. They are also responsible for investigating doctors who, for whatever reason, may need to be reprimanded. Medical boards have continued to give Dr. Byrne licenses despite his track record, which raises what seems like an obvious question, how exactly do medical boards vet doctors?

Christopher Werth: Coming up.

Robin Kemp: I was thinking, how did he end up in Oklahoma? How did he end up here? How did we end up with him?

[advertisement]

Christopher Werth: All right. Karen, you just told us about this string of malpractice lawsuits in this small town outside Oklahoma City, including Marquita Baird's.

Karen Shakerdge: Yes.

Christopher Werth: You mentioned that Dr. Byrne had left the hospital where she was treated. Where did he end up after that?

Karen Shakerdge: What I know from the records is that he started practicing at a new hospital by 2005. The hospital was called Craig General at the time, and it was located in the northeast corner of Oklahoma, about an hour out from Tulsa in a small city called Vinita, which is located in the Cherokee Nation.

Robin Kemp: My first impression was grateful that we had an OB-GYN, because rural areas, it's sometimes difficult to recruit providers.

Karen Shakerdge: I spoke with a woman named Robin Kemp. She was the director of nursing at Craig General Hospital when Byrne worked there. Initially she was happy they had an OB-GYN, but that feeling of being grateful changed somewhat quickly.

Robin Kemp: It was probably within the first six months. There's just things that he did or said that just seemed odd.

Karen Shakerdge: Robin would eventually be one of several Craig General staff deposed in lawsuits against Dr. Byrne, most of which also named the hospital. One patient claimed that while she was having a routine procedure done, Dr. Byrne tied her fallopian tubes without her consent. Her case eventually settled. This is all part of what I've come to think of as a second cluster of cases in Oklahoma that I'll tell you about more in the next episode. Robin told me this kind of pattern of multiple cases was very unusual. Do you remember what you were thinking as some of the information was coming out about these various cases?

Robin Kemp: I was thinking, "How did he end up in Oklahoma? How did he end up here? How did we end up with him?" I was angry. How did Oklahoma let him have a license? Why?

Christopher Werth: What have you managed to learn about what the medical boards in Oklahoma or New Mexico, for that matter, knew about the track record that you've been reporting on before they decided to give him a medical license?

Karen Shakerdge: Yes, to me, that was the key question here. What did they know? Because one of the things I've learned is that Dr. Byrne hadn't disclosed information about his history when he first applied for a medical license in New York. The state's investigation in the early '90s found he hadn't disclosed that he'd been reprimanded by the North Carolina medical board years earlier for administering ketamine to a patient when he wasn't supposed to, and then omitting that from the patient's medical record. I tried to find out what these other medical boards did know. First things first. Can you just introduce yourself?

Amanda Quintana: My name is Amanda Quintana and I am the interim executive director for the New Mexico Medical Board.

Karen Shakerdge: New Mexico was the first state to grant Byrne a license about a year after New York revoked his license there. I just want to be clear, though, that Amanda wasn't working at the medical board at the time. She was learning about Byrne as we talked through some of the records that the board had shared with me.

Amanda Quintana: I do know that the board licensed him as an MD in 1992.

Karen Shakerdge: We first talked about what I mentioned in the last episode, the fact that Byrne got a medical license, then a resident license, which is what doctors typically have when they're in training.

Amanda Quintana: I don't know the reason for him having a resident license in the middle of his MD licensure.

Karen Shakerdge: Is that unusual?

Amanda Quintana: It's a little unusual. Yes, it's a little unusual.

Karen Shakerdge: There was one document in particular I wanted to ask Amanda about that I think gets at your question about what did New Mexico know about Byrne's history?

Amanda Quintana: Yes, just tell me the page number.

Karen Shakerdge: It's a letter written by the New Mexico medical board about Byrne's application. Page 209.

Amanda Quintana: 209. Okay.

Karen Shakerdge: It explicitly states the board thoroughly reviewed all of his records, including the complete history of proceedings in New York and North Carolina.

Amanda Quintana: [unintelligible 00:15:12] thoroughly reviewed.

Karen Shakerdge: Then it goes on to say he completed an extensive continuing education program in New York State during the time when the board was reviewing his credentials. The board was satisfied that Dr. Byrne possessed the integrity and competency to practice medicine in New Mexico.

Amanda Quintana: There you have it. [laughs] Do you have a question about that letter?

Karen Shakerdge: My question is that the letter clearly acknowledges that the board was aware of what happened in New York. I think a lot of people might be surprised to learn that the board was aware and continued with the granting of the license.

Amanda Quintana: Yes, I'm also surprised. Again, way before my time, our board does not-- This wouldn't happen currently.

Karen Shakerdge: Why wouldn't this happen today but it would happen back then?

Amanda Quintana: I couldn't tell you. I wasn't around back then.

Karen Shakerdge: What do you make of this letter?

Amanda Quintana: Just exactly what it says. You know what? I'm a little bit-- Can we stop this interview, please? I need to--

Karen Shakerdge: Do you want me to stop recording?

Amanda Quintana: Yes, please. I want to get the full file and I can answer questions via email.

Karen Shakerdge: Okay. I did send Amanda a few more questions after we spoke, but she wrote back saying that she didn't have any further comment.

Lyle Kelsey: This was one of my first cases that I was aware of.

Karen Shakerdge: I also spoke with the executive director of the Oklahoma State Medical Board, Lyle Kelsey. He started just before Dr. Byrne got a license there. You've been there for a while now?

Lyle Kelsey: Yes, I have. 26 going on 27 years.

Karen Shakerdge: I managed to get some records from Oklahoma as well. What those records show is that the board initially denied Dr. Byrne's application. Can you tell me a little bit about the concerns?

Lyle Kelsey: I think there were some questionable things on his application that started our concern about his practice patterns and so on.

Karen Shakerdge: Then just four months later, the board reversed that decision and granted him a license. Is it fairly common to have a license denied and then granted a handful of months later?

Lyle Kelsey: No, it's not the common. Denials are pretty rare.

Christopher Werth: Who exactly sits on state medical boards like the one that you're talking about here?

Karen Shakerdge: Yes. Lyle, as executive director, he runs the medical board's operations. It's the board members who make the licensing decisions. Yes, typically medical boards are made up of mostly practicing doctors. They're often appointed by the governor, but it can vary state by state. Most also have some people who aren't doctors also, who are referred to as public members or lay people.

Christopher Werth: Were you able to find out anything about what that board based its decision on?

Karen Shakerdge: Yes. According to the records the board shared with me, Byrne submits new evidence, mostly letters from other doctors in New Mexico vouching for him, but also one from William Grant. He was the person who oversaw that educational program Byrne did in upstate New York that I told you about in the last episode. The medical board did set some conditions for Dr. Byrne's license. They required monthly reports about all surgical procedures that he did and that other doctors would review his charts. After a while, Byrne asked for those conditions to be lifted, and they were. About a year later, the members of the board allowed him to practice without any of those conditions.

It sounds like it's really the doctors that have the power to make a decision about who is getting a license and who is not.

Lyle Kelsey: Absolutely. Absolutely.

Karen Shakerdge: Something I've come across over and over again is that there are some questions about that power that medical boards have, and whether they do enough. For example, one report from the organization, Public Citizen, found that more than half of doctors nationwide who've had privileges suspended or revoked by hospitals, didn't face any actions from medical boards.

A number of people have told me that medical boards don't always work in the public's best interest. That in part, because it's physicians who are regulating their peers in some ways, that there's a inherent conflict of interest there.

Lyle Kelsey: I don't think there is. I think the board members take it very serious. They treat other doctors with problems tougher than I've thought they would, many, many times. There always could be examples of that going on.

Karen Shakerdge: Given the number of malpractice cases that have been filed against Byrne, I wondered how boards keep tabs on doctors after they grant licenses. What I learned is that doctors do have to renew medical licenses every few years and answer a series of questions, including ones about malpractice claims. I've seen some of Byrne's applications which I got from Oklahoma. What those show is that there are some discrepancies between what's on his renewal applications and what's in the court records that I have. How does the board make sure that what the physician is submitting is accurate?

Lyle Kelsey: You don't know. Do we hope that the doctors do the right thing? Absolutely. We also know that they're just like the general population too. They can tell lies and be dishonest as well. We license almost 30,000 licensees in 14 different professions. Somewhere, you have to hope that they're all being honest when they renew their license and answer questions.

Karen Shakerdge: Do you think that hope is enough when it comes to a profession of people who are taking care of patients? Does that work out okay?

Lyle Kelsey: I'm not so sure what your question is. Of course, you recognize that it's a learned profession, highly educated people, and you would presume by that, that these people would be honest and forthright in answering questions. Occasionally we may find out that somebody has lied on their application and that becomes then a fraudulent application. I don't think there's anything wrong with hope.

Christopher Werth: Something I'm curious about, you mentioned that medical boards, they don't just license doctors, they discipline them too, right?

Karen Shakerdge: Yes, that's right. They're responsible for both things, licensing but also investigating doctors and then disciplining them.

Christopher Werth: Was Byrne ever disciplined in Oklahoma or in New Mexico as far as you can tell?

Karen Shakerdge: No. Neither New Mexico nor Oklahoma disciplined him. During the time he practiced in both states, in all, 14 patients filed lawsuits against him for alleged malpractice. 7 of those settled, the other half were dismissed. One hospital temporarily suspended his privileges, but nothing, as far as I can tell, happened to his medical licenses. All of this is part of why I've come to think of medical boards as just one part of this whole world of patient safety and doctor discipline, because there's so much that goes on at the hospital level or in a doctor's office that might never rise to the attention of a medical board unless someone wants it to.

Lyle Kelsey: The license is just, do you meet the requirements to get a license in a state? Once you get that, it's pretty hard to monitor. You hope that, and there's that hope again, you hope that hospitals are doing their part to monitor and make sure that their doctors are doing well and performing up to certain standards and requirements.

Karen Shakerdge: I saw this all very clearly when I started to really dig into what went on with the staff and patients at the new hospital Byrne had moved on to near Tulsa, and generally speaking, the power that hospitals have to keep things quiet.

Christopher Werth: In our next episode, how the staff at one hospital began to keep tabs on Dr. Byrne.

Robin Kemp: If Oklahoma would give him a license, then the only people to stop him were us.

Participant 12: The damage was done and thank God I survived. I just wanted him stopped. I wanted him to lose his license and not be able to practice, which apparently didn't happen.

Christopher Werth: Imminent Danger: One Doctor and a Trail of Injured Women was reported by Karen Shakerdge and edited by me, Christopher Werth. It was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center. Our executive producer is Ave Carrillo. We had additional editing by Nsikan Akpan, Stephanie Clary and Sean Bowditch. Ethan Corey is our researcher and fact-checker. Jared Paul is our sound engineer. He also wrote our theme music. We had additional reporting and producing from Jaclyn Jeffrey-Wilensky, Owen Agnew and Katherine Roberts.

Special thanks in this episode go to Dr. Humayun Chaudhry, Rob Christensen, Dan Epstein, Ruth Horowitz, Joe Nikram, Dr. Katherine Kula, Dr. Benedict Landrin, Dr. Christopher Roy, Maggie Stapleton, Nadia Sawicki and Gina Vosti.

Janae Pierre: Thanks for listening. Be sure to check out NYC NOW every Saturday morning for the next two weeks to hear the conclusion of Imminent Danger. Trust me, it's worth it. I'm Janae Pierre, and we'll be back with the local news and headlines first thing Monday morning. Until then, have a great weekend.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.