You Couldn't Say It Was Wrong

TOBIN: Kathy.

KATHY: Tobin.

TOBIN: Super exciting announcement.

KATHY: Ehhhhh.

TOBIN: You have moved to New York.

KATHY: Not officially yet.

TOBIN: I mean like you’ve basically moved here.

KATHY I mean I signed a lease, whatever that means.

TOBIN: It means that my secret plan has worked.

KATHY:I can’t believe you actually made it happen. I don’t understand how it happened.

TOBIN: It happened because you love it here, right? Versus LA.

KATHY: No! I mean New York is fine. But I love LA because I love a temperate 72 degrees all year round.

TOBIN: Uh-huh.

KATHY: That’s what I love, that’s what I want. I don’t like having winter clothing. I don’t like having summer clothing. I generally just don’t like having clothing, so.

TOBIN: Well, you know what you already have down about being a New Yorker?

KATHY: What?

TOBIN: You’re grumpy.

KATHY: Ok. [LAUGHS]

[THEME]

VOX 1: From WNYC Studios, this is Nancy!

VOX 2: With your hosts, Tobin Low and Kathy Tu.

[THEME ENDS]

TOBIN: So Kath…

KATHY: Hmhmm…

TOBIN: I would say something our listeners write in a lot about is their experience being queer and religious.

KATHY: Yes, totally. And a lot of these folks are navigating how to hold space for both of those things in their lives, especially if the religion they belong to has been not-so-friendly to queer folks.

TOBIN: Right. Which brings us to today’s story. It comes to us from a guy named Mike.

[MUSIC]

TOBIN: Which do you think you could give up more easily? Being gay or being Catholic?

MICHAEL: [LAUGH] Uh...they’re just both so baked into my identity, I can’t imagine my life without either one.

TOBIN: Mike was born and raised Catholic. He’s also reported on the Catholic Church for the last 10 years. He’s written for The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, The Atlantic and he now writes for America Magazine, which is like the Catholic magazine. And he says he’s constantly faced with what the Catholic Church think of him as a gay man...which is not always good. Especially now.

MICHAEL: It’s been probably the most difficult time in the decade or so I’ve been doing this to be a gay person writing about the Catholic Church.

TOBIN: He’s had to report stories about people in the Church blaming gay priests for sex abuse scandals...queer people getting fired from their Church jobs when they come out or get married...

MICHAEL: There’s been times where you’re reporting and you’re just like, “Oh my god, these people really don’t like gay people,” but I just have to keep on writing.

TOBIN: So looking to the Church at large is kind of a losing game in terms of finding a way to keep the faith as a queer person. But Mike says if you dial down and look at individual members of the Church. There’s other kinds of stories about Catholicism and gay people. Stories that prove to him that the two can co-exist. Where devout, straight Catholics can find a way, through faith, to accept gay people.

MICHAEL: Which is how I got interested in the story of this nun.

TOBIN: Her name is Carol.

<<music out>>

MICHAEL: the first question...just because someone who has a difficult to pronounce last name as well, I've been trying to guess yours and my best guess was Balto-savitch?

CAROL: Pretty good.

MICHAEL: Yeah?

CAROL: If you've heard of Manischewitz wine.

MICHAEL: OK.

CAROL: Baltosiewich.

MICHAEL: Baltosiewich. OK.

TOBIN: The first thing you should know about Carol is that she grew up very Catholic.

CAROL: Very Polish, very Catholic.

TOBIN: And eventually she became a nun. But the second thing you should know about Carol is that she was not the kind of nun you are imagining. She did not wear a habit or teach in a school room. She was actually a nurse for most of her career...working in ERs and ICUs throughout the midwest.

[MUSIC]

CAROL: That was my thing it was blood and guts. I needed something that was like stimulating. I need cardiac arrest or blood coming in or Humpty Dumpties.

TOBIN: You know, putting people back together again.

[MUSIC]

TOBIN: In the mid 80s, Carol took a job as a homecare nurse.

MICHAEL: In this small, sleepy city called Belleville. It’s about 20 miles east of St. Louis.

SONG: In the town called Belleville is St. Louis, there’s a nurse named Carol, people’s homes she visits.

MICHAEL: So her job is basically to make house calls. She’d show up at people’s homes and offer the care they needed. One of her first patients was...a woman had had some kind of leg surgery and her husband was caring for her.

SONG: One of her patients needed leg wound cleaning.

CAROL: And I had to show the husband how to soak the leg, how to wrap it.

SONG: Carol taught the woman's husband to do this thing.

MICHAEL: And he couldn’t quite get the cleaning and dressing of the wounds down.

SONG: But he didn’t quite do it right.

CAROL: And I said what I need now is a big bucket, and we need to get some water and heat it and then he said, “OK.” And so I asked, “Where we going, where's your bucket?” and he said, “It's out in the barn.”

SONG: When Carol asked for the bucket the husband told it was in the barn. Why would this woman’s post surgery leg cleaning bucket be in the barn? In the barn, in the barn, it could only do harm. He had been soaking it in the cow trough.

MICHAEL: What? She saw this trough of water and she asked him well ok where’s the bucket to bring in the water to kind of sterilize it.

CAROL: The water was in the the cow trough, OK, because they didn't have running water in the house.

SONG: A cow trough is meant for a cow’s drinking.

CAROL: And I said you've been soaking her leg in the cow trough?

SONG: Yes. A cow trough is not meant for post surgery leg wound cleaning.

CAROL: And I came home I was covered cobwebs and straw and stuff and I said to my boss, “Where the hell did you send me today?”

[MUSIC ENDS]

TOBIN: Huh. Anyway. Carol was working in farm country, and she was assigned to another patient. She didn’t know much about him, just that he was sick, and that his family lived way far out.

CAROL: So I went out there and I thought, “Why is she sending me all the way out there?” Because it's like an hour drive, a little bit over an hour drive, one way.

MICHAEL: There was a young guy who had moved from this rural part of Illinois to New York City.

TOBIN: He’d planned to make a life for himself in New York, for a couple reasons.

CAROL: Number one, he was gay and his family did not know that.

MICHAEL: And he didn’t feel like he had the community he needed back home.

CAROL: And also to follow his dream, which was theater.

MICHAEL: So he moved to New York. Seemed to thrive a little bit. He got a job at the Joffrey Ballet.

CAROL: Which really impressed me because I love the Joffrey.

MICHAEL: But then he got sick, so he moved home with his parents. And Carol was assigned to help take care of him. So she drove out there and quickly learned that it wasn’t just another patient. This was a young guy who had been healthy and athletic and now he was really dying, wasting away.

[MUSIC]

TOBIN: Carol remembers it as the first time she had encountered a patient with AIDS.

MICHAEL: So she had to act as a nurse, even though there was not much she could do medically, to help him. And she also had to act as something of a social worker to help his parents navigate the healthcare system, the insurance problems, people who wouldn't come to take care of him in terms of doctors and other nurses. And she grew really frustrated because she was used to being able to solve problems, and on this one she couldn’t.

MICHAEL: The first patient you encountered that you were doing home care for. What happened?

CAROL: He died. He wasn't home very long. Less than six weeks and he was dead. I came back and I said to my boss, I said “I think we are gonna have to get educated if this is what we're going to be seeing.” and If we're going to take care of ‘em then we're gonna have to get education because AIDS was just coming we were hearing about it. But there is nothing a whole lot out there as far as how to treat things.

T: And Carol started seeing more patients with the same story. The AIDS epidemic was accelerating rapidly. At the beginning of the 80s, the research foundation amFAR says there were just a couple hundred reported cases of patients with AIDS in the US. By the time Carol meets her first patient with AIDS in 1987, the number had grown to nearly 50,000.

CAROL: It just kept on coming back to me because every now and then we’d get one. You know come coming home either from California or from New York. And it was always the triple whammy. You know the kids dying. The family finds out he's gay. And then he's got AIDS. And at that time with AIDS from the time of diagnosis to death was less than a year.

TOBIN: Carol felt like there was so much she didn’t know. She hadn’t grown up knowing basically any gay people. And now as a nurse treating this new illness, she didn’t know how it spread. She didn’t know how to care for patients who had developed symptoms.

MICHAEL: So she decided to talk to her supervisor and ask what else she could learn about how to care for people with AIDS. And she found out that there wasn’t a whole lot for her to do down in Belleville.

TOBIN: So she pitches him this idea: What if she went on like a semester abroad to a place where so much of the research and treatment was going on? What if she went...to New York City?

[MUSIC]

MICHAEL: Which was crazy ‘cause had never been there, she’s never visited. She finds another nun named Mary Ellen who is willing to go with her. She finds herself a place to live in Hell’s Kitchen. She finds hospitals that will hire her for six months. And then she’s on a plane to New York.

[MUSIC ENDS]

[MIDROLL]

MICHAEL: Just to start. Just tell us a little bit about where we are right now where the interview is taking place and how long you lived here.

JIM: Is there a point to that?

TOBIN: This is Jim Derano. Mike and I are sitting with him and his husband, Jim Wake, in their apartment.

TOBIN: So they can imagine where we are, that sort of thing.

JIM: So they can have a mental image?

TOBIN: Yeah, exactly.

JIM: We're on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in the shadow of Columbia University and Barnard College and St. John the Divine Cathedral. And we’re a block from Riverside Park...

TOBIN: OK, so while Jim gets into our exact location, let me give you an idea of what the apartment looks like. It is decked out from floor to ceiling.

JIM: It's decorated in a very eclectic manner with tidbits from our lives...

TOBIN: Colorful paintings of drag performers line the walls, porcelain figurines are displayed across the mantle and on the coffee table in front of us, and everything has its exact place. You get the feeling that maybe the tchotchkes are alphabetized.

JIM: And Will would like to throw all of it out. [LAUGHS]

TOBIN: Yeah there's so much stuff here. I imagine like everything has a story.

JIM: Everything has a story, a memory, a person attached to it, a place.

TOBIN: For example, this small, laminated card that Jim is holding in his hands.

TOBIN: Wait, what am I looking...The Saint.

JIM: It's my membership card. [LAUGHS] Can you believe that?

TOBIN: Wait, Tell me more about The Saint.

JIM: You’ve never heard of The Saint? Oh my God. It was the Vatican City of gay life.

[MUSIC]

JIM: It was a beautiful disco on the lower east side. And it was the epitome of gay disco in New York City. It opened, you had to become a member to get it to become a member you had to go down for three interviews - like getting a job on Madison Avenue. And you know if you get into The Saint you were like like a triple A gay. It was like unbelievable. And people would do anything to go. They would beg you, you could take a guest. So everybody wanted to be your friend and go with you to The Saint. It was fabulous, it had a dome over its dance floor. The music was just unbelievable, the sound system. I remember one party at The Saint had Grace Jones come down from an opening in the ceiling on ropes. Singing.

TOBIN: So insane.

JIM: It was...it was insane. There were a lot of drugs unfortunately and fortunately I did them all. And people danced for 24 hours without dropping. You go there on Friday night and go home on Sunday morning.

[MUSIC ENDS]

TOBIN: Jim remembers when he first started reading reports about the AIDS crisis in 1981.

JIM: I can remember the article that came out in The New York Times. I was on fire island. We were vacationing and we read that article and said, “What in the world could this be?” And I knew nothing about this new disease. No one did.

TOBIN: Jim was a researcher working in hospitals and eventually started doing work for Gay Men’s Health Crisis. Will was also in the city working as a nurse.

WILL: And at that time I was a volunteer at Gay Men's Health Crisis. And that's when Jim and I met. Jim and I met in March of 1985.

TOBIN: Aside from both volunteering at GMHC, Will and Jim had something else in common.

WILL: You know, it’s important to tell you guys from the get go that in terms of identifying as being Catholic, Jim and I have always done so. And you know being Catholic is important to us as identifying as being gay.

TOBIN: He says back then, they weren’t officially members of a parish, but they went to services and sang in a choir, so Catholicism was very much a part of their lives. But to be Catholic and gay during the AIDS crisis was...complicated.

PROTESTORS: Stand up! Fight back! Fight AIDS! Fight back! Fight AIDS! Fight back!

TOBIN: At the time, groups like ACT UP were leading protests around the city, against the government, against pharmaceutical companies, and, against the Catholic Church.

MICHAEL: The Church’s teachings on gay people was not complicated. The Church condemned homosexual acts as sinful. That played out in pretty homophobic ways. It meant you had Church leaders opposing legislation that would have given some rights to gay people in terms of housing, employment, certainly any talk of recognizing same sex unions or relationships. They were opposed to that. And the Church in various parts of the country, like in New york, was still a really powerful political player. So what they believed and what they said and what they advocated for mattered. And they advocated against public health measures that promoted safe sex.

TOBIN: But Mike and Jim said they just couldn’t give up their faith. They still considered themselves Catholic.

MICHAEL: What made you stay and not walk away?

JIM: Culture. I came from an Italian American family. The Church is part of our history. Italians have been Catholics for 2000 years. And it's like having an abusive mother. The next door neighbors might think it's just horrible that your mother is slapping you. But you on the other hand are upset and you’re hurt your mother is slapping you. But it's still your mother.

TOBIN: There was also this other thing going on, something you might not expect. One of the biggest providers of care to people with HIV/AIDS was the Catholic Church. At one point, the New York Times reported that the Church dedicated $35.8 million to create nursing units to treat patients with the illness. There’s a whole history of priests and nuns willing to be on the front lines working with the most vulnerable populations. And the AIDS crisis was no different.

MICHAEL: So this is the New York that Carol arrives in...in 1987.

[MUSIC]

CAROL: I remember coming across the 59 Street Bridge and everything was just huge and big and amazing and coming at you like oh my god. And then when they drove up in front of Sacred Heart Convent, I looked at this area, like...seriously?

MICHAEL: They lived with a group of nuns in Hell's Kitchen. Hell's Kitchen today is very different than it was back in the 1980s. It was a place that suffered a lot of crime. There was a lot of addiction present. A lot of poverty. And this group of nuns lived and sort of ministered in that neighborhood.

CAROL: I remember the sisters told us, “Number one, don't walk next to a building because someday'll probably stab you. And if you're here six months, you'll probably get mugged.” OK.

MICHAEL: They’d arranged to work at the two large Catholic hospitals in New York: St. Clare’s and St. Vincent’s. St. Vincent’s was down in Greenwich Village in the heart of the gay scene in New York, so they took care of a huge number of patients with AIDS.

TOBIN: So when Carol had called up to ask about coming, she says her host at the hospital was like...

CAROL: “C'mon down,” he said. Because he said, “I've got a floor of 50 some beds with AIDS. I've got a overflow to General Hospital.” He said, “Today I probably got about 192 inpatients with AIDS.”

MICHAEL: So the idea that these two trained nurses would come and help him out for free is like a godsend.

TOBIN: So Carol had come here like a good missionary. She wanted to learn how to care for the dying, you know, what the medical treatments were. But she quickly found herself confronted by another challenge, which was just getting used to gay culture.

MICHAEL: Carol’s patients in Belleville, they were these isolated cases. Where often young gay men had moved home from big cities to be with their families as they died. But that meant she wasn't getting exposed to their culture. She didn’t understand what gay culture was and how to care for a person rather than a disease. She remembers this one patient in particular

CAROL: They just wanted somebody to go up there and talk with him or listen to him. So that's what I did. He went into the bathroom that time and I picked up that magazine...Better Homes and Garden. But inside the Better Homes and Gardens was, I don't remember, it was The Advocate or one of those gay magazines. Ohhh, ahhhh well... this is interesting and it was of different sexual poses and stuff like that. And I’m like...And then when he came out and you know and I talked to him and I said "do you do this kind of stuff. And yeah he said "it'd make a difference?" And that's what it kind of I said I just had to be honest i said, “I really don't know.”

[MUSIC]

CAROL: It was a shock to know that people did this. Number one this type of sex. And then the other types of sex that went on. Uhhh, instruments that they used The type of sex. Threeway sex, ah, you name it.

MICHAEL: It was really difficult for her. For example, when she was working on the AIDS hotline…

TOBIN: ...She would sometimes answer informational calls at the hospital...

MICHAEL: ...she would field calls from usually men who were calling in with questions about how HIV was transmitted. So she said it was just question after question about different sex acts.

CAROL: Lot of stuff about the gay lifestyle. There were questions about people wanting to know what they're talking about these baths. Some people would just call up to scream and shout and yell at you their anger.

MICHAEL: So you have this nun who has to answer all theses different questions about gay sex. Different positions, what guys are doing. She has no idea how to answer them. One day she’s kind of just fed up with this. Not judgemental, she’s not uhh, she’s not looking down on them; just has had too much of this kind of conversation. So she finds herself walking home one night and thinking “What am I doing here?” Which is why I think it’s lucky she met Jim.

JIM: I had a Catholic school education and you know you hear people complaining about nuns and how mean they were. Mine were all wonderful. I had wonderful nuns. I remember to this day. I loved most of them.

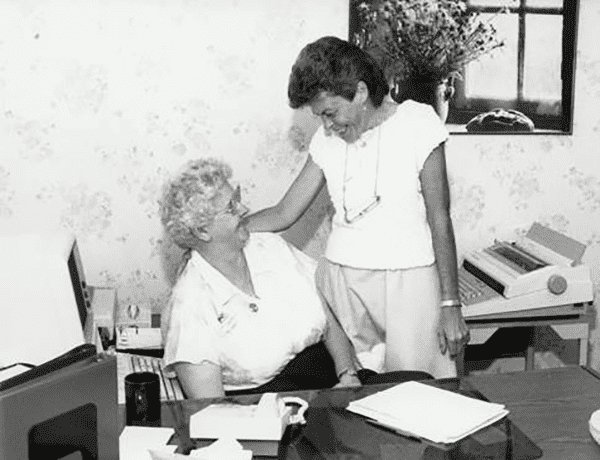

MICHAEL: Jim was active in AIDS healthcare, which is how he and Carol crossed paths.

CAROL: Jim was tall, normal weight, I’d say. Dark hair. Not bad to look at. I thought he was good looking.

MICHAEL: And eventually he introduced Carol and the other nun, Mary Ellen, to Will.

WILL: I liked the fact that they were eager and I like the fact that they were green. And you know they weren’t brass and they weren't aggressive and assertive like New Yorkers are.

JIM: I was impressed with them because at the time there weren't very many nuns that I knew personally that were focused on AIDS.

WILL: I'm not gonna as far as to say that they were country bumpkins but there seemed to be a naivete.

TOBIN: And they knew it wasn’t a time that anyone could afford to be naive.

JIM: I wrote the first safer sex guidelines for Gay Men's Health Crisis. And at that time, people were not used to talking about sexual behavior bluntly. Especially people who weren't gay talking about sex that gay people had. So I don't think most people were comfortable with talking about things like fellatio or anal intercourse, et cetera. And it became necessary, though, to do AIDS prevention you had to talk about safer sex. And you had to outline explicitly what that meant. So I don't think most nuns were familiar with that kind of language.

MICHAEL: So he’s basically like, if someone asks about hooking up in a bathhouse, you better know what a bathhouse is. Or if someone asks you if they can contract HIV from anal sex, you better know what that is, and tell them to use a condom.

CAROL: You can't even begin to talk about AIDS, you can’t even begin to minister to AIDS. You can't even deal with it until you first face your own prejudices and biases.

MICHAEL: What made you feel comfortable just kind of telling them like it was?

JIM: Well, that's the only way to talk about the truth.

MICHAEL: Will and Jim wanted Carol to be out there seeing people who were at risk for contracting HIV/AIDS.

CAROL: They took us down to Times Square at midnight. Hello New York. Whoa.

[MUSIC]

TOBIN: Keep in mind, this was not the Times Square of present day with its fancy lights and its fancy theaters and its fancy M&M store. This was Times Square in the 80s.

CAROL: You could see the pimps. These young girls...I mean 13, 15 years old with these mink coats. This was just a whole different world.

TOBIN: Jim and Will also took her to gay bars. She remembers seeing guys dressed in certain ways and asking, “What’s up with that?”

CAROL: How come some of them are wearing leather and some aren't?

MICHAEL: Or like guys going to different dark parts of the bar and asking, “What’s going on over there?”

CAROL: Where’s he going with that towel?

MICHAEL: And she said Will and Jim would tell her kind of directly.

CAROL: It was anonymous sex and you just went in there, you stuck your butt in the air, and somebody was gonna do ya.

MICHAEL: She just kind of kept asking, maybe get a little embarrassed and shrink back a little bit, but then come back with the next question.

MICHAEL: So they were like your gay guardian angels while you were in New York?

CAROL: [LAUGHS] Right, yeah.

[MUSIC]

TOBIN: That immersion into the scene, into the culture, it started to change things for Carol. She started to get to know her patients as people. One night, back at the convent, Carol was sitting on the stoop, and a guy she recognized from the hospital walked up. His name was Rob and he’d been around to care for his partner Josh, who had AIDS.

CAROL: He was just shaking and he was crying. And he saw me sitting there and I stood up and he said “Hi sis.” And I said “What’s going on Rob?” And he said “Josh is dying.” And he’s like “I can’t do anything about it.” And all I could do was hold him. And then he walked away. And then Mary Ellen told me the next morning that he had died.

[MUSIC]

CAROL: You couldn't say it was wrong. I mean the love that was there. To see the you know the care, the concern, the tenderness, the compassion that they showed for each other. You just watch that and is this wrong? This can't be wrong. I started looking at my whole life. That’s when I started to look at my own self and I think that’s when I came to the grips of, “Who is Carol and where does Carol want to go in life?”

TOBIN: After 6 months—treating patients, spending time getting to know them, learning about a whole different world—Carol decided to leave New York and go back to a place she felt like she could call home: Belleville. And when she got there, she went back to her church with a new mission.

MICHAEL: She’s armed with all this new knowledge, this new insight, and this energy to do something to help. She spends a few months working with the local gay population to figure out what they need, what already exists, and how she and her order of sisters might help. And eventually decides that they’ll open a sort of drop in center for people with HIV/AIDS.

[MUSIC]

CAROL: We opened an AIDS hotline. If anybody wanted to call in, we could answer questions. And if anybody needed resources, they could come. And we decided to name it Bethany Place because Bethany was the closest that the lepers could come to Jerusalem, to the holy city. And AIDS was known as the modern day leprosy. And we thought, well that would really fit. And Bethany was the place where Jesus came to be with his friends. We said that he could go there, take off his shoes, and have a beer with Mary, Martha, and Lazarus. That’s the atmosphere we wanted to create.

MICHAEL: It was the first of its kind in the state. She was eventually appointed to a state government task force on HIV/AIDS. She really became an advocate in that part of Illinois for people with AIDS.

TOBIN: Bethany Place would grow into one of the largest HIV/AIDS resource center in the St. Louis area. It’s actually still going today, serving hundreds of patients with outreach programs, transitional housing, and counseling.

[MUSIC]

TOBIN: Carol eventually retired. She still lives in Belleville. And even though she says her relationship to the Church is complicated—who’s isn’t—she still considers herself to be a Catholic.

TOBIN: So, Mike, just to bring this whole thing back to you. I’m wondering, why are you so interested in Carol’s story? Like, what does she teach you?

MICHAEL: I think what surprised me most about Carol was that she had lived through this really traumatic time but didn’t seem at all phased by it. It was kind of like this is just what you have to do when you confront this challenge. And I think a lot of people just wouldn’t have done anything. I mean, a lot of people did do nothing. For much of my life, I’ve been trying to understand, like, my dual identities as a Catholic and a gay man. And I think especially for gay Catholic people, sometimes there’s a sense that things won’t change, and maybe it’s not worth the risk. But with Carol, I think we saw someone do something that was meaningful and impacted a lot of people’s lives for the better. And she was courageous.

TOBIN: Does the existence of these people, you know, people like Carol, help you have faith?

MICHAEL: Yes.

[MUSIC ENDS]

TOBIN: Michael O’Loughlin is a reporter based in Chicago. He’s currently working on a book about the Catholic Church’s response to the HIV/AIDS crisis in the US. Special thanks this week to Anna Marchese.

[CREDITS MUSIC STARTS]

KATHY: Ok, and that’s our show.

TOBIN: But before we go, we have a special project in the works and we need your help.

KATHY: In the months ahead, we’re going to be exploring the ways that the economy is built for straight, cisgender people…

TOBIN: ...and how queer people navigate that system. Maybe it’s in planning a wedding, or trying to figure out how to get healthcare, or start a family. You know, there are so many times that money plays a part in the milestones in our lives.

KATHY: So we want to know: has there been a time when you’ve noticed you’ve had it harder navigating money than your friends who aren’t queer?

TOBIN: We want to hear about it. Record a voice memo telling us about your queer money moments and send it to nancy@wnyc.org. That’s nancy@wnyc.org.

[MUSIC ENDS]

[MUSIC]

TOBIN: Oh and special shoutout to Brian Dolphin who contributed music to this episode. Here he is to play us out.

BRIAN: Producer: The inimitable Alice Wilder. Production fellow: The excellent Temi Fagbenle. Sound Designer: The exigent Jeremy Bloom. Editor: The preeminent Jenny Lawton. Executive Producer: The penultimate Paula Szuchman. Your hosts are Tobin Low and Kathy Tu. Nancy is a production of WNYC Studios.

[MUSIC ENDS]

KATHY: Great filial piety.

TOBIN: Filial piety. I’ll take that a la mode.

[LAUGHS]

Copyright © 2019 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information. New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.