7. The End Of The Promises

INTRO

ALANA: I’ve noticed that outside of Puerto Rico, many people seem uncomfortable calling the island a US colony. In English, you’ll hear the word territory, or commonwealth. Protectorate, even.

And that used to be the case in Puerto Rico, too. But not anymore.

COLONIA MONTAGE: Carmen Jovet- “Hay muchos en Puerto Rico, muchos, muchos, aun dentro de su partido, que dicen, que SI, que Puerto Rico es una colonia, por eso es que se llama de descolonización”

Calle 13- “Eso es, ser una colonia completamente”

Ancla canal 4- “Por que Puerto Rico es una colonia de los Estados Unidos”

YouTube person- “Somos colonia de los Estados Unidos”

Ricky Rossello- “Una colonia”

Marica Rivera- “Una colonia”

Ruben Berrios- “no sea una colonia”.

People would twist themselves into pretzels to avoid the C-word. And there’s a reason for that.

YARIMAR BONILLA: Puerto Ricans were promised that they weren’t a colony.

ALANA: This is Yarimar Bonilla. Yarimar is a political anthropologist. She writes about places like Puerto Rico, Guadeloupe, and Curacao which are not independent states.

She has a column in the Puerto Rican newspaper, El Nuevo Dia and she’s also written for outlets like the Washington Post and the Nation.

Lately, she’s been tracing the evolution of how Puerto Ricans think about our relationship to the US and how that has been transformed by the many challenges of the last decade: a debt crisis, hurricanes, earthquakes, and now a global pandemic.

YARIMAR: what's crazy is that being a Puerto Rican-ist now requires you to also be like a disaster-ologist. And I guess now also an epidemiologist.... and an economist.... and a historian.

All this crisis has led to a reckoning in Puerto Rico. That promise that Yarimar mentioned… about not being a colony…. it’s pretty much been broken.

In 1952, Puerto Rico had adopted this new political status called the ELA, the estado libre asociado. Or free associated state -- which doesn’t really mean much.

In English, we call it a Commonwealth. And what does that mean? Is it like the Commonwealth of Massachusetts? No. Is it like the commonwealth of Canada? Also no. Commonwealth doesn’t really mean anything concrete, but it’s the kind of word that made everyone feel better about the US having a colony.

The Estado Libre Asociado, the ELA, promised self-governance, but not independence. It was a kind of compromise (or a type of brega) created by the island’s first elected governor, Luis Munoz Marin. In order to massage the continued colonial interests of the US in Puerto Rico and present a sovereign future to his residents, Marin came up with this label that sounded like decolonization.

YARIMAR: He thought that, since it had all this language of decolonization, he thought that he could set legal precedents to kind of, “if you build it, they will come”, like if you build it, they will decolonize kind of idea. And then, meanwhile, the United States, they're like, well, we're going to pretend that we're decolonizing, but we're not really going to decolonize. So it's like both parts were kind of calling each other on their bluff.

It kind of reminds me of this like Seinfeld episode that I love where like George Costanza meets up with the parents of his deceased fiance and he tells them he has a house in the Hamptons and they know it's not true...

SEINFELD SOUND BYTE- GEORGE: “It's a two-hour drive. Once you get in that car, we are going all the way... to the Hamptons. (LAUGH TRACK)”

YARIMAR: And they all get into a car and start driving to the Hamptons. And they also all know that the others know that it's all a farce.

SEINFELD SOUND BYTE- GEORGE: "Almost there."

- ROSS: "Well, this is the end of Long Island. Where's your house?"

GEORGE: "We, uh, we go on foot from here."

- ROSS: “All right!”

YARIMAR: So I basically. like we've been in a car with the United States, headed to the Hamptons when we all know there's no house in the Hamptons. You know? (Laughs)

IFE THEME MUSIC

BILLBOARD

From WNYC Studios and Futuro Studios, I’m Alana Casanova-Burgess and this is La Brega. In this episode: the charade is over.

What’s the afterlife of Puerto Rico’s political experiment?

IFE THEME MUSIC ENDS

ALANA:

There’s some indication that Luis Munoz Marin and the US Congress both knew there was no house in the Hamptons.

In 1950, while testifying in a House committee (on public lands) hearing, he said: “If the people of Puerto Rico should go crazy, Congress can always get around and legislate again.”

That’s what he said in Washington DC. But in Puerto Rico, he claimed this new status would be a definitive end to (quote) “every trace of colonialism.” Part of the promise of the ELA was that it was supposedly the “best of both worlds”: self-governance with the protection of the US military and the mobility of a US passport. It was also imagined as a key to prosperity -- having a link to the wealthy US, while also being able to manage our own affairs.

But that was 70 years ago. And recently, this idea has been dealt some severe blows.

Fifteen years ago, a recession became a debt crisis, which is now an austerity crisis. Then, in 2016, during two Supreme Court hearings, the US government itself pushed the argument that Puerto Rico wasn’t really sovereign after all.

YARIMAR: And so now suddenly the US flips the coin and they're saying, no, you are a colony. What are you talking about? You were never decolonized. You never had sovereignty. And in this moment where suddenly we're like, wait, what is happening?! Yeah, we've been saying that we were a colony. But what does it mean when you say it?!

ALANA: The next nail in the coffin came in 2016. It was a law named, unironically, Ley PROMESA (or promise). That’s the federal law that installed a fiscal control board to manage the island’s finances -- and implement austerity policies in order to service the debt.

These series of events created an awakening. In response to the PROMESA law,, protestors declared that the time of the promises was over.

[SE ACABARON LAS PROMESAS, PLENA COMBATIVA]

Se acabaron las promesas -- the ELA had been a lie, something between Puerto Rico and the US had been broken.

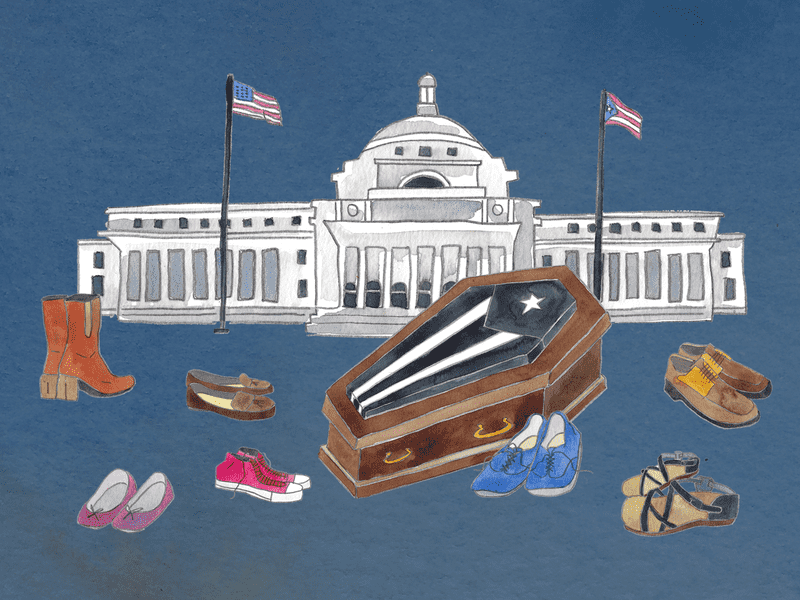

YARIMAR: After all these revelations people started talking about the death of the ELA, the death of the Commonwealth. And I became really fascinated by that idea. Like, what, what does it mean for a political project to die?

ALANA: You've described to me before these funerals. Right. With like coffins. Almost like performance art, I guess?

YARIMAR: Yeah. People would be carrying an empty coffin inside of it was supposed to be the ELA that they were going to bury. And then sometimes they were funny, like some they would be women in black with veils crying like they were mourning, you know, this body. But there was another one that was held in front of the Capitolio where there were all these performance artists. And they decided to do a velorio for “that which never existed”. So like a kind of wake, funeral and a wake for something that never was. Like, what died wasn't a thing. It was a set of hopes. It was a set of promises.

ALANA: This feeling of death was suddenly everywhere. In what some called a sign of mourning, black and white Puerto Rican flags started popping up, instead of the red white and blue one. There were murals denouncing colonialism, too.

And then, came the deaths from Maria -- not metaphorical, not performative, but thousands of lives lost in the aftermath.

And here, here is where maybe Puerto Rico could have used the benefits of the island’s murky relationship with the US to rebuild from the hurricane. Instead, President Trump threw his infamous paper towels, and the White House slowwalked funds, leaving many residents without electricity for nearly a year. Some people are still living under tarps, three years later.

So now, that word colony is on everybody’s lips - the veil has been lifted - What happens when the promises are broken?

This isn’t some theoretical political crisis. It’s really an existential one. With an economic collapse and public sector pensions slashed, we’ve seen a mass exodus from the island, families looking for jobs elsewhere, better education for their kids. People are fed up -- tired of putting up with it… tired of having to bregar, of having to endure. And you can feel it in the air.

So Who, in this dire time, still believes in Puerto Rico’s current status?

YARIMAR: Who feels who feels decolonized in Puerto Rico? Who's like: “we're good”. I want to start at the beginning. I want to think about what was the ELA promised to be and who believed in that promise? Who was it who said we had a house in the Hamptons?

ALANA: Yarimar decided to start right at home, with her grandmother.

MONSY: (SINGING) “Ay, Ay, ay, ay canta y no llores, porque cantando se alegra cielito lindo los corazones.”

YARIMAR: That voice you hear is my 93 year old grandmother. Maria Monserrate Fuentes Gerena, better known as Monsy. She loves to sing, in fact it’s hard to get her to STOP singing

YARIMAR: Acércate más al micrófono.

MONSY: (SINGING) Acercate mas, y mas Pero mucho más. Y bésame así, así como quieras tú.

YARIMAR: Like many Puerto Ricans I grew up very close to my grandmother, she was always around telling me to fix my hair, asking if I was really going out dressed like that,

and basically helping raise me along with my mother.

Maybe because she was always around, it wasn’t until the recent pandemic that I was able to really spend long hours talking to her about her life, her political views, and the many changes she’s witnessed in Puerto Rico.

During the pandemic we’ve spent lots of time joking around and filming funny videos for Instagram where her handle is @Badmonsy.

YARIMAR, MOTHER AND GRANDMOTHER: (SINGING) Me levante..

This is us, with my mom, singing Bad Bunny:

YARIMAR, MOTHER AND GRANDMOTHER: (SINGING) por que dicen por ahi que están hablando de mi. Que se joda, que se joda, que se joda, eh....

No joke, my grandma really does love Bad Bunny. She thinks he has a potty mouth, but a good heart.

MONSY: ¡Ay a mi me encanta Bad Bunny! A mi me encanta él. Habla malo, pero actúa bien.

The pandemic has also given me a chance to discover her surprising brushes with history:

MONSY: Yo fui a un cumpleaños de Muñoz Marín. Yo te lo dije.

It turns out she had gone to a birthday party for none other than Governor Luis Muñoz Marin. She was invited by a suitor who coyly asked if she’d like to join him at a birthday function. When he explained who the party was for she lost it.

MONSY: Y yo: ¿que qué!? Yo Me volví loca.

I asked her what she wore to this special occasion. And unsurprisingly she dressed in red, the color of Muñoz’s party.

MONSY: No, yo me puse un set de pantalones rojo

YARIMAR: y con una pava.

MONSY: Oye, una pena que en esa época no había celular. Yo no tengo un retrato de eso.

She wore a bright red pantsuit and a pava (the straw hat traditionally worn by Puerto Rican peasants). This was her homage to the color and symbol of Munoz’s party - the Populares.

She’s bummed there weren’t cell phones back then so she could have a picture, not just of her slamming outfit, but of this historic encounter.

You see, part of why this event was so meaningful for her is because Muñoz’s party, the Populares, was a big part of her childhood.

She loves to boast that her father (my great-grandfather) was one of the “original populares” - one of the first to cast a vote for this new party that was full of promise.

MONSY: Papá fue de los primeros populares, de los primeros que votaron.

JALDA ARRIBA CONTINUES- “Jalda arriba va cantando el Popular, jalda arriba siempre alegre, va riendo...”

She has vivid memories of accompanying him to political meetings as a teenager. And of seeing her town of Lares covered in party flags.

What she remembers most fondly about those times is the conviction and commitment of the political leaders.

MONSY: Ramos Antonini. Ese hombre tenía una palabra y era bien bueno.

She fondly remembers Ernesto Ramos Antonini, the well-known black socialist lawyer who was one of the founders of the party, but her favorite, of course, was Luis Muñoz Marín.

Just looking at him, she says, inspired confidence. She loves to talk about how he would go to the chozas of the jibaros, homes with dirt floors and few belongings, and have coffee with the residents in the little cups they fashioned out of hollowed out coconuts.

MONSY: Y él decía que sabía mejor ahí el café.

YARI: (LAUGHS)

MONSY: (LAUGHS) Él decía que sabía mejor en el coco.

He swore the coconut cups made the coffee taste even better. Every time she tells the story, something about that small gesture of grace really gets to her.

She’s convinced that he really did love Puerto Rico and just wanted the best for it.

MONSY: Él sentía, amaba a Puerto Rico, él lo amaba, él lo amaba.

This kind of uncritical nostalgia is a common staple among Puerto Rican abuelitas. But actually, Luis Munoz Marin did a lot to erase rural life through his emphasis on industrial development. But for my grandmother, it was all about eradicating the poverty that she grew up with.

Bread, Land, and Liberty: that was the promise. And my grandmother believed in it because she saw it with her own eyes: lands were being massively redistributed, even her uncle got a parcel.

During this time, industry was also arriving, homes and schools were being built.

MONSY: Y siguió mejorando y siguió mejorando.

For my grandmother, everything was getting better and better.

The ELA really did seem like the best we could hope for, the best of all possible worlds.

MONSY: (HEARTY LAUGH) Lo mejor de los dos mundos. (LAUGHS)

DEEPAK The people of Puerto Rico felt, “hey el ELA - lo mejor de los dos mundos”.

This is Deepak Lamba Nieves. He’s a development planner at the Center for a New Economy and a good friend.

Deepak argues that the ELA was never really about decolonizing Puerto Rico. It was about using Puerto Rico as an economic experiment, as a counterpoint to Communism during the cold war

DEEPAK: So much so that people from different countries across the world used to come to Puerto Rico to learn about our model and try to implement it in their countries.

Progress Island Clip: Building into the clean blue skies, the island is one the move: apartment complexes, bilingual schools, modern hospitals, luxury hotels. Progress can be seen everywhere. This is Puerto Rico - ‘Progress Island, USA’.

To the outside, the ELA was sold as an economic success story -- a global ad for using tax incentives to lure foreign investment.

Progress Island Clip: With the help of a generous tax incentive program, hundreds of businesses both large and small have grown and prospered here.

But all that economic growth was built on unsustainable compromises. From the beginning, there was an over reliance on tax incentives, which Washington could enact and take away as it pleased. Already, by the 1970s, CBS news called into question whether the commonwealth system was really bringing prosperity to the island.

CBS 1975 News: 60 percent of Puerto Rican families are living on incomes below the federal government's poverty level. Sixty percent of Puerto Rico's inhabitants need food stamp help. Whatever the past virtues of the island's relations with the United States, today's troubles raised some basic questions about this system in the future. And some argue flatly it no longer works.

If it was apparent in the 1970s that there were flaws with this project, it’s even more obvious now. Because once the tax incentives were taken away, companies started fleeing Puerto Rico. And the government took on massive debt to stay afloat.

By 2016, it became clear that Puerto Rico was descending into what economists literally call a “death spiral.” Everyone began putting pressure on Washington to pass some kind of debt relief.

Among those making the rounds on Capitol Hill was Deepak. He thought…

DEEPAK: Hey, there's another way of addressing the Puerto Rican dilemma with certainly the economic situation and ultimately also the debt issue.

He was initially confident about the impact he could have. He assumed he would be taken seriously. After all, he’s a smart guy who works at a fancy think-tank, where they had developed a solid cost-effective plan.

But Washington politicians had no time for him. This made him so upset, he had to switch to Spanish.

DEEPAK: Básicamente lo que estaba era a la luz de los ojos de ellos, mendigando por un “handout”, o una plegaria para que por favor no nos, no nos hicieran daño.

Deepak says they made him feel like he was begging for a hand out or (worse) praying for mercy. He returned from DC convinced that Puerto Rico was quite simply a colony. And he decided that the island just doesn’t matter to the United States.

DEEPAK: Nosotros..... no le importamos a gran parte de los Estados Unidos.

During our conversation, I noted something he was wearing: a baseball cap with that new black and white Puerto Rican flag.

DEEPAK: For me, the black and white flag represents a sense of mourning and also we need a symbol of resistance.

DEEPAK: Puerto Rico is going through some of its most ugly colonial periods. I didn't live through some of the historic ones which I've read about, which were out and out, violent regimes. But this feels violent to me. And this is my way of saying I fly this flag, too, because I certainly feel it represents the current historical moment and how my country is doing.

As far as Deepak’s concerned — the ELA, is done. It’s over.

DEEPAK: Este entendido político ya se acabó. Esto se acabó.

YARIMAR: But even after everything, believe it or not, there are some who still think the ELA is the best shot we have and who continue to cling to the idea that it is the “best of both worlds”.

ALANA: After the break, we’ll meet some of those people. This is La Brega.

MIDROLL --

ALANA: We’re back, this is La Brega. Puerto Rico has been undergoing an existential crisis. There is a consensus building, a lot of people see that the relationship with the USA is broken. The commonwealth status, known as the ELA, is not working.

But what makes some people want to keep holding on?

Yarimar Bonilla has been meeting them, trying to find out why.

YARIMAR: One of the strange things about the current moment in Puerto Rico, is that while huge numbers of locals are migrating out, many Americans from the fifty states are increasingly moving to the island. There are some, like hedge fund manager Peter Schiff, who routinely go on TV to talk about the virtues of moving your business to Puerto Rico.

The government takes most of what I earn. But if I earned money in Puerto Rico, thanks to the fact that they finally reduced taxes there, I get to keep a lot more of what I earn.

Peter Schiff has been quite vocal about how he considers that the ELA status is great because there are special tax exemptions for entrepreneurs like him. His investment in the status quo is clear. So, I decided to talk to someone who moved here for… let’s say… different reasons.

ROYAL PALM TURKEY: SOUND

CASSIE: I think that's going to be in the background.

YARIMAR’S MOM: WOW----It’s not Thanksgiving..”

ROYAL PALM TURKEY: “LOUD GENTRIFYING TURKEY CALL”

CASSIE: Don't worry....You're ok turkey.

YARIMAR: That's Radio Gold.

ROYAL PALM TURKEY: “LOUD GENTRIFYING TURKEY CALL”

Cassie Kaufman runs the YouTube channel “LifeTransPlanet”. Which is basically videos of her and her family living their best lives in Puerto Rico.

CASSIE: It's a royal palm turkey.

YARIMAR: I feel like he's wearing a tuxedo,

CASSIE: Right? (LAUGHS) It’s black and white.

Cassie lives on the west side of the island in Rincon, which she calls “Grincon.” The nickname comes from the many United States-ians who have migrated to the surf town over the last few decades.

Cassie and her husband are originally from Colorado, and moved here partly to escape the cold weather. I was attracted to Cassie’s videos because of the way she gushed about living here.

LifeTransPlanet clip: So some people may question why we choose to live in Puerto Rico. Especially with the earthquakes. There’s economic difficulties here on the island. But here’s a few reasons why we love living in Puerto Rico and we wouldn’t choose anywhere else in the world to live.

While others complain about everything that’s wrong from the power grid to the local bureaucracy, Cassie uses her channel to rave about the wonders of the tropical lifestyle –- she swears she is happier and healthier here -- she even lost 30 pounds! She loves that she can grow her own food, and be surrounded by palm trees, chickens, and (especially) those turkeys we heard.

But Cassie’s not just here because of the landscape, she also loves the people. And she’s aware of the resentment generated by fellow United States-ians who come to the island to simply bask from tax incentives.

CASSIE: I see, you're just coming here to benefit from Puerto Rico, but not really contribute to that. And so that's why I try to be clear, like we're here to start our family, to live in the community, to be part of this.

For Cassie, Puerto Rico’s a place that brings out her adventurous side.

CASSIE: In some ways, like I think that's what's so cool to me about Puerto Rico, is that it's this like transition land.

That phrase “transition land” stood out to me.

A transition to or from where? Is transition land just a different way of describing purgatory?

What feels like exclusion and second class status for Puerto Ricans… to Cassie means greater freedom.

YARIMAR: Do you feel like you live in a foreign country?

CASSIE: In some ways. If Puerto Rico were just another state, that would for me, it would have very little appeal. We could go to Florida and, you know, go to the beach and have a tropical experience. But to me, what attracted me, was that it was different. It was like it was just enough US that it would be more comfortable to move here.

For Cassie, that means using the same currency and banks, and not having to worry about visa issues — while enjoying the perks of living somewhere where she could speak Spanish and bask in a different culture. To her, it really is the best of both worlds.

YARIMAR: Do you feel like you live in a colony?

CASSIE: I wouldn't know what it feels like to live in a colony.

Is probably in the sense of the military kind of control or that it's a military outpost basically still. That kind of has that “old colony feel” in the sense that we don't have the right to vote.

YARIMAR: For you personally, you were willing to give up that right?

CASSIE: I guess that would be kind of a part of the definition of living under a colony, right?

When I asked for her thoughts on status, she was more ambiguous.

YARIMAR: How do you feel about statehood?

CASSIE: I don't have a horse in the game. I don't feel like that's my call. If it were a state, I would still probably love Puerto Rico. And if it weren't, I would still love Puerto Rico.

In some ways that’s the only thing she could say. I would’ve been shocked if she said she wanted it to be a state or an independent country, rather than this “transition land”. Because the fact is, she loves it the way it is. It works for her.

CASSIE: I wouldn't want Puerto Rico to lose her identity as a place. I think that's probably the fear of becoming a state. I'm also of the opinion, as you know, to to keep the culture and keep.. the sabor de la isla (short sigh).

This echoes fears long expressed in many corners about losing our Puerto Ricanness. Over and over again, people express worries about losing things like our Olympics team or beauty pageant contestants, and even our language - and say that this holds them back from calling for statehood.

But on the other hand, I don't think that there could ever be a…pull ourselves away from the US completely either. And I think that's where we kind of get in that place of let's just stay where we're at, ya know?

Cassie is not the only one. There are plenty of locals who also say… let’s stay where we’re at. And the populares—the political party that brought us the commonwealth to begin with — are still an important political force.

MUSIC TRANSITION

PLENA JINGLE “CHARLIE DELGADO PA GOBERNADOR”- Charlie Delgado para Gobernador. ¡Si! Lo quiere la gente..

REGGEATON JINGLE “Eduardo Bathia 2020”- Cuando nos unimos logramos grandes cambios, cuando nos juntamos a PR rescatamos, lo fortalecemos, lo recuperamos, todos de la mano ahora vamos....al rescate de la vida...”

YARIMAR: ¿Cuál es tu jingle favorito?

SWANNY: Es bien fácil. Se llama Creo, de Aníbal Acevedo Vilá (LAUGHS).

This is Swanny. She’s a 20-something college student at the Universidad Interamericana (known locally as “La Inter”) and her favorite political jingle is called Creo...which means “I believe”.

YARIMAR: ¿Cómo, va ese? Yo no lo conozco.

SWANNY: (LAUGHS) Te voy a decir. Empieza diciendo: “Creo en nuestra gente, su coraje y su valor. Creo en el futuro y en el triunfo de su voz.”

EPIC “ESPECIAL DE BANCO POPULAR” STYLE POP BALLAD “Anibal Gobernador Jingle”- creo en la palabra, creo en la verdad, trabajando todos juntos, Puerto Rico brillará...”

Swanny is all in when it comes to the populares.

SWANNY: Soy yo, una popular de corazón. (HEARTY LAUGH)

YARIMAR: ¿De corazón? (LAUGHS)

SWANNY: De corazón y de mente.

YARIMAR: O sea, ¿Fuego popular?

SWANNY: ¡Fuego! (LAUGHS)

In many ways Swanny reminds me of my grandmother: that young politically engaged energy, attending political rallies with her family, with memories of hanging out the car window in the caravans, singing jingles.

SWANNY: Yo soy la persona que a cinco o seis años, yo estaba por la ventana del carro de mami en una caravana (small laugh).

And today, Swanny is the VP of the “young populares”. Which means her mission is to attract more young people to the party -- a hard task in a moment when many are frustrated with “la political vieja”.

SWANNY: Hay que decirles lo que hemos hecho y que somos.

Her way of recruiting is to focus on past achievements — particularly the economic development that the ELA represented in its heyday—in the hopes of convincing young voters that the populares are still our best bet.

SWANNY: Es el partido que pudo hacer mucho, pero que todavía le queda mucho por dar.

When I asked Swanny if she felt like she lived in a colony

YARIMAR: ¿Y tú sientes que Puerto Rico es una colonia?

Her answer, like Cassie’s, was ambiguous.

SWANNY: Hay veces que sí, hay veces que así se siente..y hay otras veces que no se siente tanto.

“Sometimes”, she says — “Other times, not so much.”

And so I asked her if she thinks — like my friend Deepak — that the ELA is dead... … And she said, no, she thinks the ELA is still alive

SWANNY: Que ha sido muy maltratado, pero que al final del día nos sigue proveyendo mecanismos para poder desarrollarnos

She recognizes that it’s taken a beating -- but says it still holds promise.

I have to admit, it surprised me to hear a young person defend the status quo so passionately.

But here’s the thing, possibly the most important thing, to know about Swanny: she is from Barceloneta.

SWANNY: Soy natural de Barceloneta, Puerto Rico.

Barceloneta is a small town on the northern coast of Puerto Rico which was once home to one of the largest pharmaceutical complexes in the world.

Swanny: Cuando Barceloneta era uno de los campos más grandes de la industria farmacéutica del mundo.

It was literally known as “the industrial city” (“la ciudad industrial”). Over 14 pharmaceutical plants were established here because of the purity and abundancy of its water reserves.

But… many of these pharmaceutical plants left Barceloneta after the federal government put an end to the tax incentives that had brought them there.

Today, the groundwater is contaminated and the factories are empty.

SWANNY: Tú pasas por la número dos de Barceloneta y ves los edificios de las fábricas abandonados, de todas las fábricas que se fueron.

When the companies left Barceloneta, many people lost their jobs -- jobs that Swanny thinks were only possible because of the ELA status.

SWANNY: Pues yo vi todo ese proceso de cómo cerraban las fabricas en mi pueblo y como todas las personas, todos los papás de mis amigos se quedaban sin trabajo. Fue un proceso bien fuerte.

For Swanny this was painful to watch. Barceloneta took a hard hit after the factories left, and many of those who lost their jobs eventually left for the states.

Perhaps this is why Swanny refuses to give up on the ELA. Accepting its death would be like accepting the death of the hometown she knew and loved.

When I talked with Swanny, she cited all the classic catchphrases of the Populares: like Puerto Rico as “the bridge” between the US and Latin America, and the importance of the US government providing “protection” in the case of natural disasters. She seemed earnest and sincere in these beliefs, but when she says that famous slogan:

SWANNY: “Lo mejor de los dos mundos.” (LAUGHS)

She says it with a laugh — because she knows it’s a cliché, and perhaps, one that’s harder and harder to believe in. And yet, the alternatives -- independence or statehood -- are unconvincing to her.

For now, she prefers sticking with the devil that she knows because she’s unconvinced that “new” is necessarily better.

SWANNY: Quizás lo nuevo al final del día, aunque suena tentador, pero realmente no es lo mejor para el país y no es lo que buscamos.

If Swanny’s Barceloneta is the symbol of abandoned industry, another town—Rio Piedras—is the symbol of abandoned commerce. If you read a news story about Puerto Rico’s debt crisis you will most likely see it accompanied by a picture of Rio Piedra’s desolate Paseo de Diego. This pedestrian mall used to be a bustling commercial district. Visitors from surrounding parts of the Caribbean would come and load up on goods to sell back home.

My mom was a master seamstress and this was a primary destination for us when I was young. Every year we would do our back to school shopping, happily combing through the big bolts of fabric at stores like “La Riviera” where we would purchase fabric for a whole semester’s worth of new handmade dresses.

Now, that's a long lost memory. Most of those stores are shuttered and the few that remain are struggling to survive.

VICTORIA CIUDADANA CARAVANA AMBI

Alana and I were recently in Rio Piedras at a time when it felt much more active. There was a caravana -- a political rally where people get in their cars and drive around following a candidate during election season. We were asking folks there if the ELA had died, and one guy was quick to answer.

GUY WHO IS QUICK TO ANSWER- “El ELA - un engaño. No murió, ni siquiera nunca nació.”

It never died. Because it was never born.

He was there supporting a new movement in Puerto Rico…that wants to stop talking about status, and focus on other fundamental issues. Like government corruption, gender violence, and the need to audit the debt.

The caravana was for the campaign of a young politician named Manuel Natal. He narrowly lost the race to be San Juan’s mayor -- and I mean narrowly. It wasn’t just a matter of a close margin -- there’s evidence that election officials botched the count. But even this near-victory was astonishing, given that Natal is from a brand new political party.

YARIMAR: So how would you define the ELA?

NATAL: It was ¿El maquillaje de la colonia?. It was a way out of putting a little bit of makeup (CHUCKLES) on our colonial relationship with the United States.

YARIMAR: A little lipstick on the pig?

NATAL: Yeah, (LAUGHS) the pig is the colony, not the people of Puerto Rico! (LAUGHS)

YARIMAR: Good!

Natal actually used to really believe in the ELA. Like Swanny, he comes from a family of populares and was once a rising star in the party. But a few years ago he made a radical decision and became an Independent, citing corruption among his colleagues.

Then, along with other progressive leaders, he helped found a new political party called “Movimiento Victoria Ciudadana.”

Its members have different visions - many are pro-independence, but some are pro-statehood, and others (like Natal) are soberanistas, meaning they want more local sovereignty while still retaining their ties to the US. But they all agree on one thing -- decolonization is necessary, and we need a new process for deciding which status we want.

For decades the political parties in Puerto Rico have been organized around status options.

And every couple of years we undergo these performative votes that are described as plebiscites or referendums.

NBC Report 1967: A majority of Puerto Rico's two and one half million people still live in the country, in the mountains and in small rural towns like this. Now, for the first time in history, they have the opportunity to vote on their own future.

Back in the late 60’s when NBC was reporting on the first plebiscite vote, they called out the irony of this spectacle.

NBC Report 1967: Most Puerto Ricans, even those who favor a commonwealth, agree on one thing. This plebiscite is at best only a temporary solution. The United States is not legally bound by its results, and neither is Puerto Rico.

At best, these are little more than opinion polls. In the most recent one last November, the statehood option won by a slim margin receiving 52% of the votes cast. But these plebiscites are non binding, they’re not tied to any legislation and have no support in Washington.

They’re basically another bluff. It’s like once again we’re getting in a car heading for the Hamptons, even though we all know there’s no house at the end of the road.

NATAL: Supposedly Einstein defined "locura," craziness, as trying to do the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. And what we have tried in Puerto Rico? We have tried the plebiscites in which the political parties are the ones that lead the process and at the end of the day nothing has happened. So what are our other alternatives?

Natal’s party proposes one such alternative, what they call a “constitutional assembly” - in which representatives of each political option would negotiate directly with Washington the terms of each status choice.

And what would this do? Ideally, it would bring concrete answers to enduring questions, like:

Would we have dual citizenship if we were independent?

Would towns like Barceloneta get tax incentives for manufacturing under statehood?

Would we have access to federal programs like Pell grants as an Associated Republic?

And maybe the most delicate question but also the most important one --

Would any of these options be tied to reparations for over 120 years of colonial rule?

What Natal and others suggest is that debates over status have kept us from dealing with other fundamental questions.

NATAL: In the country that we want to live, whether it's a state where there is a free country, where there is an association with the United States. What's that society, right?, or what does it look like? Is it poverty and inequality that currently represents most of our island? Is it a society in which there's prosperity and social equality? And that's, I think, the discussion that more and more people are interested in having.

This idea is appealing to the many young people that have grown frustrated with the long standing impasse in Puerto Rican politics. These are the ones that marched in the streets to oust the governor in the summer of 2019. And In this past election, they started a viral voter registration campaign on social media.

Among them was my grandmother’s favorite trap artist Bad Bunny, who officially endorsed Natal.

.

I started the pandemic posting videos of her on social media, joking that she was “La Influencer”. But by the time the political campaigns were in full swing, she had become a bonafide social media sensation.

BAD MONSY INSTAGRAM VIDEO

MONSY: ¡Dime hija!

YARIMAR: ¿Por quien vas a votar?

MONSY: Pues, ¡Yo quiero un cambio, pero un cambio radical

YARIMAR: ¿Radical?

MONSY: Radical

I posted a video of her in a rocking chair, where I asked her how she was gonna vote this time around. She surprised us all by saying that she supported the pro-independence candidate Juan Dalmau. The conventional wisdom was that only young voters were supporting the alternative candidates like Natal and Dalmau, and that older voters were afraid of change. To which she said:

BAD MONSY INSTAGRAM VIDEO= MONSY: Dicen que los viejos que no votan por Dalmau. ¡Poorrraej!

¡Porra eh!

Her video went viral, Dalmau even used it for one of his TV spots, and then the morning shows came calling --

NOTICENTRO EN LA MAÑANA - NORMANDO VALENTIN - Como todo una influencer, como BAD MONSY ha conquistado las redes sociales por sus videos…”

She then wrote and sang a political song that also took off --

NOTICENTRO EN LA MAÑANA

BAD MOSNY: (SINGING) “Ni azules ni coloraos, ni azules ni coloraos,

NORMANDO VALENTIN “¡AJA!”

BAD MONSY: (SINGING) ¡Yo quiero la patria nueva que nos propone Dalmau!

NORMANDO VALENTIN: “¡Ahi esta!” (LAUGHS)

And the weekend before the election, Dalmau himself actually came to visit her and brought her flowers which put her over the moon.

BAD MONSY AND DALMAU MEET VIDEO - BAD MONSY: “No lo puedo creeeeeeer!!!!” (LAUGHS)

After a lifetime of voting for the populares, and of supporting the ELA, her public support of an independentista was surprising.

But it doesn’t mean she wants independence itself.

BAD MONSY: No, no Independencia, por ahora.

She told me she voted for Dalmau simply because she thought he would make a good governor. This might not sound revolutionary, but in Puerto Rico it is.

As far as the status, she felt like that could be dealt with later.

BAD MONSY: Entonces después se podía bregar con lo otro. ¿Tu sabes? Poco a poco.

So maybe her transformation isn’t that radical -- like a good popular she thinks we should just kick the status can down the road, bregar with that later.

But you know who is really kicking that “status can” down the road, really hard-- all the time?.

The US Congress. THEY refuse to commit to anything, or to even speak clearly about why it insists on keeping Puerto Rico as an ambiguous “transition land.”

So, where does that leave us? Honestly, I don’t know, but I’m skeptical of the options currently on the table.

For example, when I consider independence, I get excited about the possibility of being our own country, but then I look around at our neighbors in the Caribbean and see that many have the same challenges as Puerto Rico: indebted economies, austerity regimes, huge diasporas, challenges of disaster recovery, and battles over corruption. Independence is clearly not a silver bullet. It doesn’t guarantee sovereignty. Instead of battling the fiscal control board, we might end up battling the World Bank or the IMF.

But when I consider statehood I think of Hawaii and how the native population there was shut out of much of the prosperity and development that statehood supposedly ushered in.

Or I look at the movement for Black Lives in the US, and the discrimination suffered by people of color in the States and it makes me wonder if anything other than second class citizenship will ever be available to us.

So I end up back where we’ve been for all these years: at an impasse. Yet, something feels different about the current moment.

The signs of change might be subtle, but they’re there: in the ubiquity of the black and white protest flags, in the dark lyrics of a Bad Bunny song, and in the transformations at the ballot box, as thousands moved towards alternative candidates.

In the end, I think the closest thing I’ve found to an answer of what I want for us, is something my mom said one night, as she jumped into the conversations with my grandmother.

Tiene que suceder algo diferente, que no es lo que ya está, porque lo que ya está funcionó en un tiempo, pero ya no funciona, ya no funciona.

She said — Something HAS TO change, because what we have might have worked at one point, but it just doesn't work anymore.

Yo ni sé, pero yo quiero para Puerto Rico, algo que quizás todavía no lo hemos pensado, que estamos en el proceso de pensarlo.

She wants something that doesn’t yet exist, something we’re still in the process of inventing, something we haven’t thought of yet.

But this is the problem: among the many crises in Puerto Rico there’s also a crisis of the imagination. We know that what we have is not working, but we’ve been gaslit into fearing change.

And so I can only hope that this moment of crisis can also be one of transformation.

[2019 SOUNDS FROM CALLE SIN MIEDO PROTESTERS BEGINS- “Somos más y no tenemos miedo.]

We saw it during those massive protests in 2019, when thousands came together shouting “somos más y no tenemos miedo.”

—”we’re more and we are not afraid”. It’s unclear what it means to assert “we’re more” but I’d like to think it means that we’re more than just the sum of our parts, and that we can be more: more than a transition land or a disappointing compromise.

So, perhaps, if the death of the ELA and the end of the promises means anything, it’s the realization that the world we deserve is not something that can be promised, conceded, or guaranteed.

But it’s also not something that we can KEEP waiting for.

Copyright © 2021 Futuro Media Group and New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.