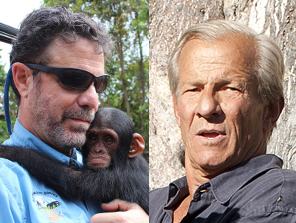

Peter Beard and Richard Ruggiero

( Photos courtesy Richard Ruggiero, US Fish & Wildlife Service and Peter Beard Studio )

Alec Baldwin: This is Alec Baldwin and you're listening to Here's The Thing from WNYC Radio.

Africa can cast a spell on people. Today, both of my guests, Peter Beard and Richard Ruggiero, have attempted to tackle the issues Africa struggles with in very different ways, one with art and one with government policy.

Nejma Beard: When you see the skies of Africa, they are so huge and you almost look into the eye of God. I can't explain it, there's something that enters your soul.

Alec Baldwin: That's Peter Beard's wife Nejma. We're at their house in Montauk having a light lunch.

Peter Beard: Anybody want anything like water?

Alec Baldwin: I know those skies she's talking about. I've been to Africa. I went in 1998 and stayed in Natal in South Africa. We were there for two months, living in a house on the edge of a game reserve. Just before we arrived, there were two lethal attacks by wild animals in the area. Signs were posted everywhere advising caution. It seemed everyone carried a weapon. I remembered an 18-year-old production assistant on the film turned out to be packing a gun underneath his shirt. Africa certainly did feel wild.

Peter Beard: And here I am interested in all of it.

Alec Baldwin: Peter Beard, 74, was born in New York City.

Peter Beard: I don't get tired ever.

Alec Baldwin: Went to the same schools as his father: Buckley, Pomfret, Yale. His great-grandfather was a railroad tycoon. His grandfather was heir to the Lorillard Tobacco fortune.

Peter Beard: We go to the tuxedo clubs. My grandfather there, Pierre Lorillard, but it's a great portrait.

Alec Baldwin: Peter Beard first felt the pull of Africa at age seven, when he stepped into the African Hall of the American Museum of Natural History. Ten years later at 17, he reached the continent with a camera in hand.

Peter Beard: I've always taken pictures.

Alec Baldwin: Since you were a child?

Peter Beard: Since before you were born.

Alec Baldwin: Right. Since you were a child?

Peter Beard: Yeah.

Alec Baldwin: Who encouraged you to do that? How did that go? Photography wasn't a mainstream hobby back then.

Peter Beard: I did have a very advanced grandmother, my mother's mother, who wanted to buy me a camera. My parents wouldn't let her. Eventually she won and I got a camera in about 1948, a Voigtlander. Hey, Nej, aren't you gonna sit here and criticize me after?

Alec Baldwin: Nejma, Peter's wife, sits about 20 feet from us. That is when she's not pacing the grounds or lighting a cigarette or checking on the food being served.

But what was photography then to you? Meaning when you started --

Peter Beard: You know it was very juvenile and like sentimental. I just liked number one how easy it was, number two I was going to school and you graduate and get out and you get pictures of the guys in your class. I got all my group. If you're ever interested, I’ve got all my albums in New York.

Alec Baldwin: Clearly, you're someone who, there's a lot of things you could have done.

Peter Beard: [Laughter]

Alec Baldwin: Right? You grew up in a very, very comfortable family. You look like a movie star. When did things with you with photography really, when did it take hold of you? When did it become -

Peter Beard: It never did.

Alec Baldwin: It never did?

Peter Beard: I'm just into subjects and things that are interesting. You can see that in the pictures, right?

Alec Baldwin: Right. So you don't consider yourself a photographer?

Peter Beard: No. Not if I can avoid it.

Alec Baldwin: You consider yourself a writer who takes pictures.

Peter Beard: I would say an escapist.

Alec Baldwin: Right. Why?

Peter Beard: Because I went to art school but I don't like the word art. And I don't like the words, I don’t like what's happening in the art world, the Chelsea million studios there.

Alec Baldwin: Yeah.

Peter Beard: I like things that are exciting or make you laugh or something like that.

Alec Baldwin: Was your father artistic?

Peter Beard: No.

Alec Baldwin: No. Did he collect art?

Peter Beard: Was Anson Beard artistic?

Alec Baldwin: Peter turned to his brother, also named Anson, who was visiting that day and sitting on a bench behind us. Eventually, Anson would join in the conversation.

What did you study at Yale, when you went to Yale? Did you go to Yale ‘cause you sound so, I don’t know what the word is--

Nejma Beard: Crazy?

Alec Baldwin: What did you say the word was?

Nejma Beard: Crazy.

Alec Baldwin: Crazy. That's his wife who's volunteered the word crazy. You sound so unorthodox so I'm assuming did you go to Yale out of obligation? Was that like a family thing or did you want to go to Yale?

Peter Beard: I was going as a pre-med and I suddenly realized going into pre-med and I'd also been to Africa two visits. Humans are the problem. So imagine being in the business of saving fucking humans.

Alec Baldwin: You went to Yale for what? What'd you study?

Peter Beard: Art.

Alec Baldwin: Did you finish?

Peter Beard: Oh, yeah.

Alec Baldwin: You did.

Peter Beard: I graduated. I did History of Art, you know, all those things. American Studies and then I went to art school and I did Joseph Alvarez in the art school.

Alec Baldwin: And when you left Yale where'd you go?

Peter Beard: Africa.

Alec Baldwin: So you knew. You'd been to Africa before you -

Peter Beard: Yeah.

Alec Baldwin: - finished Yale you'd been there twice?

Peter Beard: I went in 1955 with Charles Darwin's grandson, by the way.

Alec Baldwin: And what was the genesis of that? Was your father an adventurer? Were people in your family adventurers in that sense?

Peter Beard: My father roomed with Woolworth Donahue, who did the greatest safaris of all with a hunter I've used. Never went. He's into bird shooting and stuff like that.

Alec Baldwin: He was not an Africaphile.

Peter Beard: No he had his Salmon River. His salmon fishing and deer hunting. And he's a great guy, but he was not really adventurous.

Alec Baldwin: I hate to use this phrase, but who turned you on to Africa?

Peter Beard: Well, I guess it was 1955 with this Quentin Keynes, Darwin's grandson. We went South Africa, Madagascar, Kenya. So it was a damn good time.

Alec Baldwin: What happened to you when you were there? It became an important part of your life.

Peter Beard: Well, I've got a lot of important - not important pictures, no. I've got a lot of lousy pictures, but subject matter you know rhinos, things like that. But it was my introduction to Charles Darwin.

Alec Baldwin: Right.

Peter Beard: And I think the elimination of Darwin from our school studies and the way he's been swept under the rug, is at the root of almost all of our problems.

Alec Baldwin: Why?

Peter Beard: We don't know anything about biology, zoology, ecology or nature. We are enemies of nature. Don't ever forget it.

Alec Baldwin: Peter Beard continued to go back to Africa. He made his reputation with a book called "The End of the Game," published in 1965, which chronicles the starvation of tens of thousands of elephants and other animals, in Kenya's Tsavo National Park. He had purchased 45 acres in Kenya outside Nairobi and set up what he called Hog Ranch, named for the resident warthogs in the area.

Peter Beard: I've still got a great place.

Alec Baldwin: Peter's photographs in "The End of the Game" stay with you. They are stark. Peter described the African Hall at the museum, all those years ago as possessing 'A darkness you could feel.' The same phrase comes to mind when looking at the images in his book.

Peter Beard: It was overwhelmingly obvious that this enormous park was being eaten alive by an overpopulation of elephants because they'd had a nine-year anti poaching campaign. They arrested all the traditional hunters, they were locked up. The population soared, ate the trees and poaching was used as an excuse to continue raising money.

Alec Baldwin: What's the status of Tsavo now? What are the issues there now?

Peter Beard: Well, the bush is slowly growing back, but the corrugated iron huts have expanded from villages into little cities. The human touch is like a disease.

Alec Baldwin: And there's nothing they can do about it.

Peter Beard: Africans in Africa.

Alec Baldwin: Right.

Peter Beard: Who's gonna do anything?

Alec Baldwin: Right.

Peter Beard: The national parks were pretty much held aside for -

Alec Baldwin: Tourism.

Peter Beard: - accommodation.

Alec Baldwin: Right.

Peter Beard: Housing. You know shit houses.

Alec Baldwin: And what's the status there now?

Peter Beard: A population that was around five and a half million when I arrived, to over 40 million. Starvation and begging and going around the world looking for freebies.

Anson Beard: You might get Peter to answer that question.

Peter Beard: Yeah.

Alec Baldwin: At this point Peter's brother, now with cigar in hand, raises his hand.

Anson Beard: Speak up a bit.

Alec Baldwin: What does Peter think about the fact that Bill Gates has put so much money into AIDS in South Africa while President Umbecki pays no attention?

Peter Beard: Yeah. AIDS there is really a density dependent phenomenon, the more of it the better, frankly. Kenya is now way over 40 million from five and a half. Just think about that. That means nobody lives happily. Everybody's a crook. Everybody's on the make. Everybody's sitting, begging outside the American Embassy. It’s just - cuts the country right off. You can't survive population pollution on this level.

Alec Baldwin: Now, when you said that 'AIDS was a density dependent phenomenon' -

Peter Beard: Yeah.

Alec Baldwin: - and 'the more of it the better,' your wife was on her feet right away.

Peter Beard: Well, that's because everybody's very, very sentimental and they think 40 million Africans is gonna do a country good. No, it's not.

Alec Baldwin: Peter and Nejma met in 1985.

Nejma Beard: All right, what do you want to know?

Alec Baldwin: Nejma is Peter's third wife after Cheryl Tiegs and socialite Minnie Cushing. Peter met Nejma in Kenya, where she was born.

Nejma Beard: I'd grown up there, but I was educated in Europe. So when I came back I met Pete.

Alec Baldwin: And how much time have you spent back in Africa over the last - You met him in '85, so that's over 20 years ago. So that’s-

Nejma Beard: Well, we used to live there a year at a time. A year there, a year here.

Alec Baldwin: That's almost 30 years ago.

Nejma Beard: Well, 1985. God, you're aging me. Yes, that's true.

Alec Baldwin: But I'm saying -

Nejma Beard: Yeah, it's true.

Alec Baldwin: - so it's over -

Nejma Beard: That's true.

Alec Baldwin: - 25 years. So in the past over 25 years, how much time have you spent in Africa during that time?

Nejma Beard: Not enough at all.

Alec Baldwin: Not much. But is it safe to say though that Africa cast this tremendous shadow over both of you. You're both -

Nejma Beard: It's is in my -

Alec Baldwin: - fairly obsessed.

Nejma Beard: - soul. It's in my soul.

[Crosstalk]

Peter Beard: It's the best place to be, but it's also increasingly diminished. Like Long Island.

Alec Baldwin: How has he changed in the time you've known him? What was he like when you met him?

Nejma Beard: He was so incredibly -

Alec Baldwin: We've heard some stories.

Nejma Beard: - incredibly out there. But I thought of it as totally normal. I thought this was an incredible human being who'd done incredible things. But I do remember this really funny moment. We'd gone to some shrink for some weird reason. I can't remember what it was about. And Peter left the room to go to the loo and the chap just looked at me and said, 'If I were you young lady, I'd make a run for it.' [Laughter] That was -

Alec Baldwin: But you didn't. Why?

Nejma Beard: I'm a really stubborn wench. That's really -

[Crosstalk]

Alec Baldwin: You're all in.

Nejma Beard: I'm all in or I'm all out, basically.

Alec Baldwin: But he's a very colorful character.

Nejma Beard: He's a colorful, exhausting character, yes. That's true.

Alec Baldwin: You're married now.

Peter Beard: 25 years of bliss.

Alec Baldwin: How many children do you have?

Peter Beard: One.

Alec Baldwin: Just one. You'd had no children prior.

Peter Beard: I'm not really a reproducer.

Alec Baldwin: You're not.

Nejma Beard: We just have the divine Zara.

Peter Beard: I have said that 'Zara was an accident.' I love accidents. In everything I do, I love accidents. And people criticize me for that.

Nejma Beard: I told him before this interview if he ever said that again -

Peter Beard: [Laughter]

Nejma Beard: - I would literally attack him.

Peter Beard: What's the matter with an accident?

Nejma Beard: See.

Peter Beard: Think of Francis Bacon.

Nejma Beard: Sorry-

[Crosstalk]

Peter Beard: Visual works -

Nejma Beard: I tried.

Peter Beard: - looking for accidents.

Alec Baldwin: But you were a famous - what's the word. What should I say? What should I call him? He was a famous what?

Nejma Beard: Libertine. Womanizer.

Alec Baldwin: Well, thank you.

Nejma Beard: [Laughter]

Alec Baldwin: You were a famous libertine people say and yet number three lasted 25 years. How did that happen? What's the difference?

Peter Beard: Well, you learn. You get better -

Alec Baldwin: Yeah.

Peter Beard: - at picking something.

Alec Baldwin: You’re better picking. You picked better.

Peter Beard: You pick better. And then you just get in a sort of prayer position and go forward.

Alec Baldwin: Yeah. So in an age when people in the modern world, and the world is divided between people who don't know you at all, people who know you as a photographer and the writer of these books and this adventurer and so forth. They know you as a famous socialite, if you will. They know you as all these things and then there's young kids who surf the Internet, who you know that you're the guy that got crushed by the elephant on YouTube.

Peter Beard: The idiot.

Alec Baldwin: Yeah. What was different that day from every other day?

Peter Beard: That day we were out there, we had no security, no gun.

Alec Baldwin: It was 1996, Peter was helping a friend who was opening up a safari camp.

Peter Beard: We were basically on a picnic. We'd done a promotional shooting. Suddenly, like 15 elephants came over the hill, a cow heard. You know like they are, you don't get bulls at that stage. And it was on the very edge. It's another population story. It was on the edge of Tanzania, Quokka Mountain and elephants come in and grab a cabbage at night and they get shot. So I'm sure this is a herd that had been shot up, but they were very skittish.

Alec Baldwin: So they take the bullet and keep moving. They don't go down. They just shoot 'em to scare 'em.

Peter Beard: No, they take the bullet and move. Yeah. Doesn't do any harm.

Alec Baldwin: Doesn’t hurt 'em.

Peter Beard: Well, the way they shoot at night you know big black thing there, bam and you just have a lot of wounding. And this female gave us a demo, which is totally normal. We ran back, I was in long pants, early morning wet grass. The elephants went back up the hill so to speak and we just stood there. The sons of bitch, this matriarch came again. So then she starts coming, we start running again, make it feel happy. But it wasn't stopping. [Laughter] And I lucked into the elephant on an ant hill.

Alec Baldwin: And the thing just head-butted you.

Peter Beard: Well, no, no, no. It was many things. I was up in the air and down.

Alec Baldwin: Oh, it mauled you.

Peter Beard: And the guy with the camera took off. I think we'd run far enough so that it knew we weren't dangerous. The herd came around. The heard was you know [snorting], sniffing. It was actually almost worth it.

Alec Baldwin: That should have been the title of the book, "Almost worth it."

Peter Beard: I was completely blind by the way. My optic nerve had been bounced off. I couldn't see a goddamn thing. I had a huge hole in my leg, went right through here. And my hip was broken in seven or eight places.

Alec Baldwin: At this point by the way in the interview I want to mention Beard is hiking up his shorts -

Peter Beard: [Laughter]

Alec Baldwin: - and showing me -

Peter Beard: Especially wore his shorts for tonight.

Alec Baldwin: - and showing me, in the inner most portion of his thigh, the closest area to his actual personality itself is this hideous gash, this hole in his leg.

Peter Beard: So anyway, there was an amazing gaping hole and there was no blood coming out of it by the way, but I couldn't see it. I got splintered hips. I didn't get speared, 'cause I couldn't see the thing.

Alec Baldwin: But did you think when that happened, did you think that was it?

Peter Beard: When I was running, yeah.

Alec Baldwin: You thought that was it?

Peter Beard: Well, you can't escape an elephant.

Alec Baldwin: You thought that was the end.

Peter Beard: Yep.

Alec Baldwin: And did you think 'How romantic?'

Peter Beard: No, I thought -

[Crosstalk]

Alec Baldwin: You thought 'Fuck.'

Peter Beard: - 'I just finished your book.' [Laughter] No, I just felt like an idiot.

Alec Baldwin: So then how long did it take you to recover? You were flat on your back for months, correct?

Peter Beard: I bled out going into the hospital. It was about four hours to get to the hospital. I eventually had to be flown to -

Alec Baldwin: That’s good. What did you just say?

Anson Beard: There are no roads.

Alec Baldwin: No roads.

Anson Beard: Where they went --

[Crosstalk]

Alec Baldwin: So the man who complained that roads have ruined Africa, is the man who's sitting there going, 'No fucking roads here.'

Peter Beard: It was a very bump little ride, I'll tell 'ya.

Alec Baldwin: But even in your way and I mean you don't seem like somebody who's eager to take a bow for this or anything else. But in your way, through your work, I mean through art, through photography, do you think that you've been responsible for some of the good that's come there in terms of casting a light on that at all?

Peter Beard: Truthfully I know nothing at all. No positive result. I know lots of people who've looked at these pictures. They don't even see that this is starvation scenes. They see ivory. They think 'Oh -'

Anson Beard: They think you’re a conservationist so it's bad to kill the elephants.

Alec Baldwin: Peter's brother Anson speaks up again, saying he's heard him described as a conservationist.

Peter Beard: I'm for conservation, but it's mostly a con. That's the trouble. It's sentimental. Buy an elephant a drink, a lion an acre.

Alec Baldwin: So some of them have to die?

Peter Beard: Well, the way humans are spreading -

Alec Baldwin: Right.

Peter Beard: - the whole lot have got to go.

Alec Baldwin: So the answer is limiting human development. You’ve got to get-

Peter Beard: Of course.

Alec Baldwin: Right.

Peter Beard: Population pollution is the key. And that's the thing, but I'm afraid it's partly due to Hitler. You can't talk about population dynamics. You never hear the word, do you? You never hear pecking order, you never hear any of the words that relate to all the struggles that are going on there because we have decided not to talk about any of the realities. But it's do-gooder conservation. It's sentimental horseshit.

Richard Ruggiero: What we're talking about in essence is changing human behavior.

Alec Baldwin: Richard Ruggiero is chief of the Near East South Asia and Africa at the Division of International Conservation, at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Africa called out to him too. He joined the Peace Corps in 1981. He was placed in the northern Central African Republic. Richard spent most of the 1980s and 90s living in Africa and he doesn't see things that differently from photographer Peter Beard. Richard Ruggiero has spent over 30 years in conservation. His dissertation from 1989 was on the plight of the African elephant, a problem he's still trying to tackle.

Richard Ruggiero: You know I could describe it that if God forbid what was happening to elephants were happening to people, we would call it a massive genocide.

Alec Baldwin: Right.

Richard Ruggiero: They're being exterminated for ivory.

Alec Baldwin: On a mass level.

Richard Ruggiero: Correct. Using the latest technology and that's weapons, cell phones, satphones, vehicles, aircraft, helicopters. And the ease by which massive amounts of ivory can be illegally shipped to markets has never been greater.

Alec Baldwin: And it is primarily for ivory. It's an ivory driven market.

Richard Ruggiero: Primarily. You know, certainly there -

Alec Baldwin: What are the other uses as well?

Richard Ruggiero: Well, bush meat. People eat elephants.

Alec Baldwin: In what regions of Africa do they eat elephants? They don't export that meat do they?

Richard Ruggiero: Not really. Most of it is consumed either in rural villages, but increasingly and more disturbingly, it's exported to cities within Africa. The problem there is that it produces a market that's very, very difficult to satiate.

Alec Baldwin: Is it labeled as elephant meat when it's sold in more urban -

Richard Ruggiero: Yes. Well, it's not labeled so much as you go to a market stall and the meat's there and the person selling it will tell you what it is. It's fairly obvious to look at it.

Alec Baldwin: So people in African society, not just impoverished people, they eat elephant meat and it's a food staple to them.

Richard Ruggiero: Yeah. I mean the impoverished people who eat elephant meat opportunistically, sporadically, is nothing new about that and a lot of people would say there's nothing wrong about that given a sustainable level of off take. The problem here is that in some cases, there's an additional inducement to eat elephant meat. Number one, it's a bush meat in many places. I'm speaking primarily of Central Africa where you ask the question, 'Where does this happen most?' It happens all over Africa, but mostly in Central Africa at this point.

Alec Baldwin: You say Central Africa. Are there governments there that condone this more and encourage this more than others?

Richard Ruggiero: No.

Alec Baldwin: Who are the culprits?

Richard Ruggiero: I wouldn't say that they openly condone it, it's just by negligence or inaction, it effectively causes the problem to be worse. There are some countries that are very, very good at it and make really good earnest efforts.

Alec Baldwin: Such as?

Richard Ruggiero: In Central Africa, Gabon is clearly a leader, very progressive president who might be the greenest president on earth. Ali Bongo is his name. And the system, the ethos, the government and many people even down to villages, are very supportive of the concept of sustainable off take or respecting laws. It's not a perfect place. The problem there is the poachers are coming in very well armed from across boarders and they're killing elephants at an incredible rate. So, Gabon is working very hard on that and that does contrast with some countries who either lack the political will or, maybe this is more important, lack the capacity to do anything about it.

Alec Baldwin: Now the idea that Kenya and areas like that, which are probably the most well known I would imagine. I think the people who have that romanticized Isak Dinesen, you know -

Richard Ruggiero: Peter Beard.

Alec Baldwin: Yeah. Meryl Streep and Redford getting on a train together or getting on a biplane together. That's not the highest concentration of elephant.

Richard Ruggiero: No, no, but - certainly not.

Alec Baldwin: Well, how would you describe the populations in Kenya now?

Richard Ruggiero: Receiving increased pressure. That's a manifestation of the great symptom. The symptom is poaching. The symptom is habitat destruction. The disease is something else. And I think that's what Peter Beard alludes to.

Alec Baldwin: What do you think it is?

Richard Ruggiero: Well, it's a human-induced problem. Nature has some problems that people are not responsible for. I mean you can talk about volcanoes, tsunamis, people aren't responsible for that, but many of the problems that nature, the wildlife experience are at the hands of man to coin a phrase. So, the problem is basically people's attitudes about wildlife in general, about elephants specifically. It's a function of short-sightedness. It's a function of apathy. It's a function of greed. And it's a function of human numbers.

Alec Baldwin: Is it fair to say, and I don't have a sophisticated analogy here, but would you put poachers - even with their high-powered weaponry and satellite phones and aviation equipment and so forth - would you put them in the category more with like people who were making moonshine during Prohibition and it's more of a kind of a rag-tag bunch, it's not that sophisticated, or are they more the equivalent of Mexican drug lords who are actually controlling the regions politically and killing the political leadership that opposes them and terrorizing them? How sophisticated is poaching in Africa in terms of its political power?

Richard Ruggiero: Both exist. The unsophisticated, the poacher who maybe has a fabricated shotgun or uses snares or poison, and that still exists. It's been the case for a long time. It's the relative proportion of poachers. It's the predominance now of these more sophisticated, more aggressive, frequently militarized poachers that's happening and that's what causing this chronic problem that we've seen. It ebbs and it flows, but it has gotten dramatically worse in recent years. It's a result of, as I say, the market for ivory and the ease by which it can be obtained and technology, guns, helicopters, political background, indifference, those points come into play.

Alec Baldwin: Is it fair to say that in Gabon, where Ali Bongo is having some degree of success, what's he doing and/or not doing that's leading to that success, that other places it's getting by them?

Richard Ruggiero: First, the country or an individual or an institution needs to be aware of the problem. And I think the problem is becoming very conscious in the minds of the public, certainly politicians in Africa are aware of the problem. The next step is the political will to do something about it. And the third step is having the capacity to act on the political will. Well, Bongo has the political will and he is developing and that's what my organization, Fish and Wildlife, helps them with, is to develop the capacity to deal with the problem that the awareness has brought to everybody's attention. So the answer to your question succinctly is, he's aware of the problem, he's willing to do something about it and he's mustering the capacity and the wherewithal to actually do it.

Alec Baldwin: When was the first time you were aware of Peter Beard's photography and his work there in Africa? What was your response to that when you first saw that?

Richard Ruggiero: I was first aware of it; I think I lived in Kenya in the late 80s. We knew that Peter was out in Hog Ranch and occasionally you'd see him across a crowded room at some sort of function. But I never had close contact with him at all. We just lived in the same place, the same country. My reaction was that he is an artist and he is doing some fantastic - I was first just physically attracted to the beauty of his photographs and how he put together his books. But thinking about it farther down the road, I mean I was struck by almost - quaintness isn't the right word. That it was a reflection of a time that was fleeting. You alluded to Isak Dinesen and the Hollywood images of what Kenya was like. Certainly Peter's work had a great deal of that sort of nostalgic feel. Very, very beautifully presented, but to me there's a great function in that. And the great function, now decades after he produced his main book or his artistic displays, the photography mainly, is it shows what was. Peter's work, it's a zeitgeist. It's a representation of what things were in the '50s and '60s in Kenya. And by contrasting that, we can see how far things have gone and that enables us to predict the future, or to foresee it, or to anticipate it. And if we can't do that, we can't deal with it. We have to be proactive. That's the secret to conservation.

You have to anticipate the trend to be able to proactively deal with it. And Peter's book really gives us that sort of nostalgic or that retrospective view that's very helpful to us.

Alec Baldwin: Yeah. When I look at his pictures, it's almost like he's Frederic Remington.

Richard Ruggiero: Exactly. Yeah, that's my point. You know just from an artistic standpoint its fantastic stuff. But as I say as a historical perspective and a reminder, it has a function as well as just an aesthetic value.

Alec Baldwin: But for the sake of this program, if you had to give it a word or a phrase, how bad is it right now?

Richard Ruggiero: My 32 years of experience of watching it very closely, this is a nightmare. It is unbelievably bad. And we've been seeing it accelerating in that negative trend. So once again, it's the rate of change.

Alec Baldwin: What's the hot spot? Where is really like out of control?

Richard Ruggiero: Central Africa.

Alec Baldwin: What country?

Richard Ruggiero: The Western Congo Basin, where there's still a lot of elephants, really getting hammered. DRC, the Democratic Republic of Congo is so degraded already. For example, Iain Douglas-Hamilton estimated 350,000 to 400,000 elephants there in 1980 when he did his big continental survey. There are about 12,000 left now. So it's pretty much the end of the game there for elephants, but farther in the western Congo Basin, Gabon is an example. The Republic of Congo, that's the smaller one. There's still some elephants. They've been greatly reduced, but there's still populations that are meaningful and can be saved.

Alec Baldwin: How many are in Gabon?

Richard Ruggiero: Oh, that's hard to answer.

Alec Baldwin: Would you guestimate?

Richard Ruggiero: Roughly 50,000.

Alec Baldwin: Right. So there's in the tens of thousands.

Richard Ruggiero: Sure. There's one park called Menkebe that has probably twice as many forest elephants as the entire DRC. It's a place that the poachers know. Just received a report yesterday by the eco guards who were out looking at it and despite massive intervention by the government of Gabon, there's still big pockets of poachers. So this is a problem that sure, great to point out that there's political will in Gabon and that they have a motivated national parks agency. But when you're up against the scale of the problem, the intensity, the danger of running into people who aren't just gonna run away when they're confronted but are gonna stand in fight, this is a whole different dimension. So, the answer to your question is how bad is it. It's horrible. It's terrible. And it's getting worse.

Alec Baldwin: What's the political situation and what's the government situation there?

Richard Ruggiero: Well, DRC has been challenged by civil war for decades. Let me put it this way. It's easy to see how the government can be preoccupied with more urgent needs.

Alec Baldwin: Sure. That must be the constant problem in some aspects of that world.

Richard Ruggiero: Every country has to have priorities. When you're talking about putting your limited ability into saving peoples' lives, versus saving elephants' lives, well there's an obvious priority there.

Alec Baldwin: When you're there, when you're dealing with the people there, are you encouraged by the amount of people, the percentage of people there, native people, who care about this issue and you think are really willing to take action, or are they in the minority?

Richard Ruggiero: Well, it depends on where you are and how you ask the question. I mean that’s - I lived with them for years. But you ask them the questions, 'How do they feel about elephants? What does living alongside elephants mean to you? What do you need to do things that are good for that co-existence?' And the answer is highly variable. In some places, elephants don't really mess with people, they stay separate and that's the way both elephants and people prefer it. In other places, agriculture is tending more and more as it expands, to get into traditional elephant ranges and so that interface is now very obvious and usually when people and elephants are in conflict, elephants lose. First, people lose their crops and sometimes get trampled and that's very serious, it's tragic. But eventually the elephants get bullets.

Alec Baldwin: Yeah, people love deer in Connecticut until they eat your flowers, then they want them shot.

Richard Ruggiero: Sure. So you know it would be similar thing if you were to ask somebody whose apple crops are being destroyed by deer, 'What do you think of deer?' And they're gonna tell you that they're not very pleasant neighbors and they're bad garden pests. On the other hand, somebody who is isn't affected negatively by them can relate to their esthetic value. Africans can do that. Many of them are very proud of elephants. It's a part of their culture and their heritage. But living with them is costly in a lot of ways and sometimes there needs to be an incentive. And the disincentive is enforcing the law and frankly, while that's very important, it's only a short term solution that really doesn't get to the crux of the issue. The crux is what we're talking about and that is the attitudes of people and their willingness to co-exist with large animals that compete with people for water, for space, or in some cases are more profitable to them dead than alive. So, sure it's an economic calculus but it's not quite that simple. There are also values, pride, etcetera.

Alec Baldwin: One of the things that Beard said which was more all-encompassing on this theme of the sentimentality of the conservation movement was, you know, 'That evolution has to be allowed to take its course in Africa in all ways.' And then he said that 'AIDS was a blessing on the African continent.' That, you know, 'Something has got to happen there to reduce that population.' Do you find that in Africa, of course they don't have an economy that compares with that of the United States, few places do, but do you find that what's going on in economic policy and social policy and agriculture, you know food, energy. Things that they need for their human population to survive and develop, are those so bad that it's understandable that the elephants are gonna fall by the wayside?

Richard Ruggiero: In some places all of those factors help. In some places they're a net negative. You know, Africa is a big diverse continent and certainly there are examples of how all of those factors can work to the favor of the natural system. And there are certainly examples that in their absence or when they're poorly applied, when economic development or agricultural policy, or all of the things you mentioned, forestry. You know Central African forests are being cut to provide hardwood for international markets.

Alec Baldwin: So, making people aware of boycotting that market would be a step.

Richard Ruggiero: Well, I wouldn't say boycotting is the right term or the right approach. It's being an informed consumer.

Alec Baldwin: Sure.

Richard Ruggiero: It’s about having -

Alec Baldwin: More manageable stewardship of -

[Crosstalk]

Richard Ruggiero: Manageable stewardship. Certification, but real certification that actually works and is transparent. This is not news to anybody who's thought or spoken about these things but those practices are not yet perfected. We have an idea that those tools can be applied very well and many of the things we're talking about are tools. Development as an incentive for conservation is certainly known and it has been practiced but it's still, it’s a work in progress. Sport hunting for example, can be an excellent tool to motivate and to derive financial benefits to people who have to make sacrifices to live with elephants.

Alec Baldwin: Sport hunting of what?

Richard Ruggiero: Of elephants, of lions. They're very controversial subjects of course. Some people think elephants should never be hunted because they are extraordinary animals. Other people think of them as being subject to any economic motivation or initiative. So, there's a wide spectrum of views that sort of get more into philosophy and ethics than anything else.

Alec Baldwin: What are your personal feelings about that?

Richard Ruggiero: My bias is I've lived with elephants for years and years. I studied them for my doctorate. I took considerable risks to study them and certainly to keep them alive, so I'm very biased. To me personally, shooting an elephant for fun, for entertainment, is not cool. However, that doesn't deny the fact that other people find that okay and that there can be benefits from a well-managed system. Look, if what Peter is saying is that wildlife needs to be managed, then I think he's correct. Elephants need to be managed, so do people, in essence. Not the same way, obviously. But as the world becomes more crowded, it's incumbent on all of us to think of ways of making room for us all and not to sacrifice something like the African elephant because of our short-sightedness or greed. I’m speaking of humanity's short-sightedness or greed. So that's the challenge.

Alec Baldwin: Why do you think people - I mean in the United States where Americans are sadly as obsessed with their cable, telephone, Internet bundling charges, more than they are with the fate of species of animals around the world. Why should Americans care about what's happening to the great wildlife heritage in Africa?

Richard Ruggiero: It comes down to valuing elephants, their existence, what it means to the world. Is the world a better place with or without elephants? Because that choice is being played out passively, admittedly. But by our ineffectiveness or our inaction, we're moving toward a time when elephants are so greatly reduced. If it matters to people that such remarkable creatures, products of creation or evolution as you choose. Is the world a better place or is it greatly diminished by the loss of these animals? In my opinion, the world is a greatly diminished place. The quality of life on earth is diminished when we lose key, important things. There's a very practical function that elephants provide. They have an ecological value. They spread seeds. They dig for water. They expose salt-rich soils. In their absence, things change. Call it evolution, but it's not a natural one because it's being caused by the problem we're talking about. So there is an esthetic value to the world. There is a practical or an ecological value to the world. And in some cases there's an economic value to the world and all of those things count.

A quick thought. Think about where the North American bison was at the turn of the 20th Century. There are probably more bison, admittedly in their altered form, in North America now than there are elephants in Africa. And what does that mean? It means that people's attitude toward them, maybe it's because rich land owners want to see the natural fauna and therefore make the sacrifice of dedicating their pasture land to them. Maybe it's because they like to eat beefalo. But whatever the motivation is, bison have a value that justifies their populations going from a few hundred back in the dark days, to maybe half a million. That says something. It's not an identical case. It's sometimes dangerous to compare across taxon, across continents. But I think the concept is clear that unless people value elephants, esthetically, practically, ecologically. Unless they value them, people will cease to have a motivation to preserve them. You remember what Bob Dylan said on "Subterranean Homesick Blues?" 'You don't need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows?'

Alec Baldwin: Sure.

Richard Ruggiero: Okay. Well, you know I have a scientific background and science is the basis of everything we do and it needs to be there and it needs to be good science. But at the point we are now with what we're talking about, it's about people and understanding them and how to deal with their desires, their characteristics. And that's what we're focusing on and that's where a great deal of the hope is. You know people are the problem, but they're also the solution.

[Music]

Alec Baldwin: For more information on Richard Ruggiero, the decimation of the elephants in Africa and what you can do to help, visit Heresthething.org. You'll also see photographs by my first guest, Peter Beard.

Peter Beard: It was overwhelmingly obvious that this enormous park was being eaten alive by an overpopulation of elephants because they’d had a nine-year anti-poaching campaign. They’d arrested all the traditional hunters, they were locked up, the population soared, ate the trees, and poaching was used as an excuse to continue raising money.

I'm Alec Baldwin. Here's The Thing is produced by WNYC Radio.

[Music]

[End of Audio]