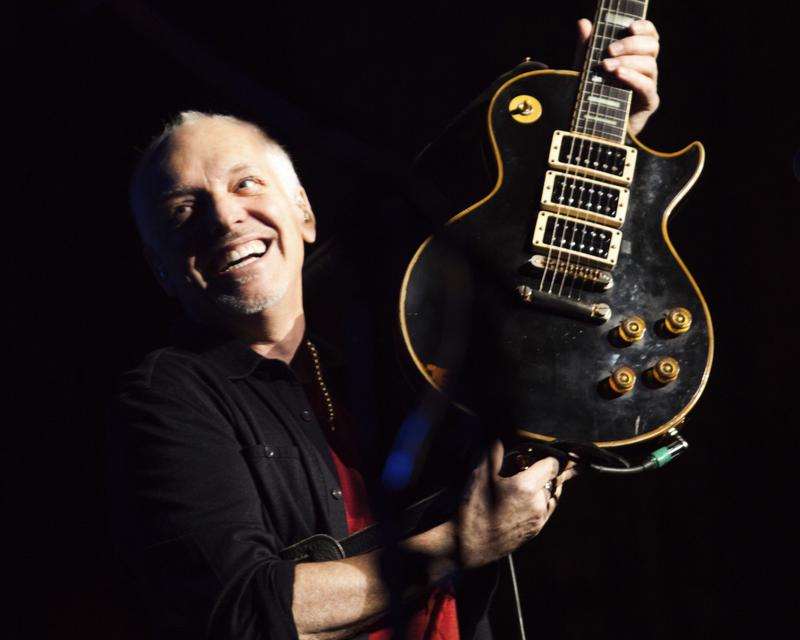

Peter Frampton

This is Alec Baldwin and you’re listening to Here’s the Thing from WNYC Radio.

[Music comes in]

Come on, admit it, if you’re my age you remember exactly where you were when you first heard this [more music].

That’s the sound of 25-year-old Peter Frampton performing what would become one of the top selling live records of all time. It was 1975 and “Frampton Comes Alive” would change his life [more music].

He was young, but hardly a newcomer. By then, he’d already made four solo albums for Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss of A&M records. He had started the band, Humble Pie, when he was 18. Frampton’s signature sound is a mixture of virtuosic guitar, a powerful voice, and this electronic device called a talk box. As it turns out, the talk box wasn’t his first successful foray into the world of musical gadgets.

Peter Frampton: I realized that I was a techie when I was very young, I got my first reel-to-reel tape machine and then I figured out that if I got another one, I could go sound-on-sound, you know, before any multi-tracking sort of thing, you know. And I figured that out pretty early. I was like, you know, 10 or 11. So I’ve been an engineer as long as I’ve been a musician.

Alec Baldwin: Do you think that’s helped you as a musician? You know, you’re talking to somebody who—your music is, like, so important to me.

Peter Frampton: Oh, thank you so much.

Alec Baldwin: I mean you talk about me, growing up when I was a kid. And you were very young then, I mean Humble Pie, you were a kid. You know, when I was growing up, there was like The Beatles, The Stones, Zeppelin, The Who, and Humble Pie. You don’t wanna know what I put in my body listening to "I Don’t Need No Doctor." I mean, you don’t want to know. My point is that, do you think that that work has made you a better musician? Because you are such a virtuosic guitarist and such a great guitarist.

Peter Frampton: Sound is very inspirational to me. I remember the reason that I wanted to learn guitar was because I heard the sounds of all these people on TV and on the radio—electric guitar--very young. And something—I have a very acute sense of sound and I’ve always had that. If I don’t have a good sound, I can’t play very well. So I’ve always worked out what makes a good sound. How do you get a good sound?

Alec Baldwin: Technically.

Peter Frampton: Technically. And then one of the first sessions I ever did, Bill Wyman of The Stones produced it when I was 14. And the first engineer I worked with was Glen Johns, who is—if people don’t know, he’s one of the most famous engineers of all time.

Alec Baldwin: Stones’ engineer.

Peter Frampton: Yeah. Zeppelin, Eagles, The Band.

Alec Baldwin: You.

Peter Frampton: Yeah. Humble Pie. And then being a gadget freak early on, I just was over—like a little birdy on their shoulder and I was—‘What’s that? What are you doing there?’ I just learned how to engineer. So I really enjoy that part of it as well, immensely.

Alec Baldwin: How do you end up as a 14-year old-and Wyman wants to produce your track?

Peter Frampton: Well, I started playing guitar just before I was 8 years old.

Alec Baldwin: Were either of your parents musical?

Peter Frampton: Yes.

Alec Baldwin: You grew up in England.

Peter Frampton: Yes.

Alec Baldwin: Where?

Peter Frampton: About 12 miles south of London in Bromley, Kent. And my mother was a—definitely would have been an entertainer but my grandparents wouldn’t allow her to become an actress. She wanted to become an actress. Her father was a singer. Yes, we have a lot of musical genes.

Alec Baldwin: And your Dad?

Peter Frampton: My dad played -- he was a teacher, artist. He played guitar in a college dance band before the war. Before the second—

Alec Baldwin: Did you grow up hearing him play guitar?

Peter Frampton: He was more into his art. But he was the one that taught me how to sing "Michael, Row the Boat" with two chords basically, and then "Hang Down Your Head, Tom Dooley" was another biggie for me. Then it was Eddie Cochran, Buddy Holly, and our English—The Shadows, Clifford and the Shadows. So that’s how I started playing guitar, because of American music, obviously. That’s what we all did. We were all clamoring for America music before The Beatles.

And then so I was known locally as this young, little upstart, good guitar player, very young. Ended up in a semi-pro band, still at school, that had the drummer that was the original drummer of The Rolling Stones, called Tony Chapman who introduced Bill to the Stones. He didn’t end up staying in The Stones, and Bill felt he owed him a favor, I would say. Said ‘Look, put a band together, and I’ll produce it.’ And he comes into the music shop I’m working on the Saturdays, when I’m about 14 and restringing guitars for the guy there. And he said, ‘I want you to be in my band.’ I said, ‘Well, I’ll have to speak to Dad,’ you know sort of thing. First thing I know, we’re in a van. We pick up Bill Wyman in Pinge, who sits in the front of the van, goes very quiet. We’ve got a Rolling Stone in the front seat. We go up to London and I meet Glen Johns, and we make a record.

Alec Baldwin: What was the record?

Peter Frampton: It was called "Hole In My Soul." And it was a cover of an American song, and—

Alec Baldwin: What was the name of the band?

Peter Frampton: The Preachers. So that was it.

Alec Baldwin: So music was your entire life.

Peter Frampton: Yes.

Alec Baldwin: You’re in the guitar shop in Kent, fixing strings on guitars for people—

Peter Frampton: Yes. Shining guitars up.

Alec Baldwin: Next thing you know, Bill Wyman’s in the car and you’re off to go do "Hole In My Soul" with The Preachers.

Peter Frampton: Yes.

Alec Baldwin: What year is this?

Peter Frampton: This is ’64.

Alec Baldwin: So The Stones and The Beatles were in full swing by then. And they were recording.

Peter Frampton: Yes. In fact that year, The Stones were given Ready, Steady, Go—they took over the show Ready, Steady, Go for one week. And each one of The Stones had their choice of act to be on, you know. And of course, Bill chose us. So I’m on TV when I’m—just before I turn 15.

Alec Baldwin: Is there any footage of that? Do you have footage of that?

Peter Frampton: If anybody’s got it, Bill’s got it, ‘cause he’s the historian, but that was pretty amazing.

Alec Baldwin: Do you miss living in England? You’re such an American in so many ways. You’ve lived here for years, haven’t you? Year and years.

Peter Frampton: Yes, ’75, I came to New York. I miss my family—my brother and his family. I miss friends and stuff, but my children are here. When I first came to America with Humble Pie, and I turned on the radio, I said, ‘I’m moving here.’ It just seemed like this was the place it was all happening.

Alec Baldwin: That was the old. This was the new.

Peter Frampton: Yeah, and I’d lived through the swinging ‘60s of London. And that was exciting too. And I love England, don’t get me wrong. I just don’t think I would ever live there again. I’d be too far from my kids.

Alec Baldwin: This is home now?

Peter Frampton: Yeah.

Alec Baldwin: So when you finished "The Hole In My Soul" on the show with Bill Wyman, he’s your selection there on the show. What happens then?

Peter Frampton: Then I’m 16. It’s school holidays in the summer of ’66. Big local band, The Herd, come to me and say, ‘We saw you in the Preachers. We’re having a changeround. Would you come and help us out for the summer?’

Alec Baldwin: 16.

Peter Frampton: So I say, ‘Okay.’ So it gets close to September when I’m going to go back to school and they said, ‘Here’s an offer. We want you to be the lead guitarist, and the lead guitarist is gonna play bass. And we want to be a four-piece instead of five-piece, and would you join The Herd? I said, ‘Whoo. I’ve got to go back to school, do my 6th form, get my A levels, and go to Guildhall School of Music.'

Alec Baldwin: Let me grow up.

Peter Frampton: That was my plan, to go to music college.

Alec Baldwin: Let me grow a beard.

Peter Frampton: Right. At least!

Alec Baldwin: Let me get a few chest hairs here, then I’ll call you.

Peter Frampton: Yeah. I hadn’t even had a shandy yet. You know?

Alec Baldwin: Exactly.

Peter Frampton: So I went to Dad and Mom and said, ‘Look, I really want to do this. This is a professional band. They’re great. They’re a big band.’ And my Dad said, ‘Well,’ and they knew that this was on the cards, that this was coming up. They knew by this time I was gonna be a musician. And so he said, ‘Well, look, if you left here and you got a job at the post office, you’d get 15 pounds a week. I want to get an assurance from this band that you’re going to get 15 pounds a week.’ I said, ‘Whoa, if he can do that deal, that’ll be great. I don’t think they earn enough to pay themselves 15 pounds.’ He said, ‘Well that’s what you—minimum wage for you.’ So that was the last deal my Dad did for me. Because we started to become a little better and earn more money. At the beginning they couldn’t pay themselves 15—

Alec Baldwin: Eventually it was a bargain.

Peter Frampton: Yeah, because they paid me 15, and they got 50.

Alec Baldwin: Your father was no Brian Epstein.

Peter Frampton: So that was the end of him as a manager [Music comes in].

Everything changed, and The Herd became—had like 3 big Top 10 hits, and I became very well known in Europe as a guitar-player, singer.

Alec Baldwin: Now, by the time you leave The Herd. You leave them in what year?

Peter Frampton: The Herd—after these 3 big hits in an album, we realized that we were losing money still, and there was no reason, ‘cause we saw the figures, what was coming in, and what we were getting paid and all that. So we reached out and Steve Marriott and Ronnie Lane of the Smallfaces said, ‘Look, we’ve been through this. We’ve been screwed by management or business manager, whatever.’ They clued us in, which was very nice of them. And said they’d help us produce a track or two on the next album we were gonna do, which they did. Meanwhile I’m sitting in with the Smallfaces now, at various functions and wanted to join the Smallfaces. That wasn’t to be. Steve wanted me to join the Smallfaces, but they weren’t so thrilled with that. So in the end, Steve called me up and said, ‘Look, I’ve left the Smallfaces. Let’s form a band.’ And that’s how Humble Pie basically formed in—right at the end of—in ’68.

Alec Baldwin: So the two of those things closely overlapped. The end of The Herd, and the forming of Humble Pie.

Peter Frampton: Yes. And it was basically two ex-teeny bopper stars. Steve Marriott was the face of ’67, and I was the face of ’68, sort of thing.

Alec Baldwin: And by ’68, how old are you?

Peter Frampton: 18.

Alec Baldwin: Now, you’re 18 years old, and you’ve been doing this professionally since you were 14 years old. And you’re in the world of rock and roll. And especially as we go from the ‘60s, from ’64 to ’68, it gets a little more grainy, if you will. It gets a little more vivid, in terms of drugs, my sense of the culture. Was that difficult for you to be the under aged man-child, you’re like Mozart—you’re like this prodigy, but you’re a kid. And you’re in this world with some—I would imagine some pretty hard-living people.

Peter Frampton: Well, yeah. I was pretty much of a late bloomer. I had to really learn to drink. You know?

Alec Baldwin: Did people expect you to?

Peter Frampton: I think so. [Cross-talk]

Alec Baldwin: They did. You’re in the band, and it doesn’t matter your age. It’s like, you’re in the Army.

Peter Frampton: Yeah, exactly. You gotta swear and drink, you know. And now, do drugs. But I passed out so many times from anxiety attacks from pot—I’m trying to get high, please. But anyway, I managed it in the end. But not really when I was with Humble Pie.

Alec Baldwin: What changed?

Peter Frampton: I think it was my solo career, and then getting to the point where it was surreal.

Alec Baldwin: We’re gonna get to that. We’re gonna get to that.

Peter Frampton: Okay, that was the time.

Alec Baldwin: So you’re with Humble Pie, and you’re in England. And you perform with them for how many years?

Peter Frampton: ’68, ’69, ’71—4 years.

Alec Baldwin: How would you characterize that period for yourself? Did you enjoy it?

Peter Frampton: Unbelievable.

Alec Baldwin: They were very popular. In the States as well.

Peter Frampton: Yes, that band brought me to America.

Alec Baldwin: Where’d you play? At the Fillmore?

Peter Frampton: Fill East. That’s where we started. I met—I mean, probably one of the first gigs I met Bill Graham. ‘How you doing?’ You realize now when I look back, it was the beginnings of—the creation of rock and roll shows. Truly. Bill Graham was the guy on how to do it live.

Alec Baldwin: Where would you record Humble Pie? In London?

Peter Frampton: We recorded at Olympic, in the famous Olympic where The Stones and Zeppelin recorded. And I did all my solo stuff there as well. Either there or Island Studios, which is Chris Blackwell’s place.

Alec Baldwin: So you never recorded in the US?

Peter Frampton: No. The first thing we ever did was record the live album of Humble Pie at the Fillmore.

Alec Baldwin: Right, and why did Humble Pie end?

Peter Frampton: A couple of reasons. I was feeling claustrophobic in the band, because we started off very democratic in doing it, all different types of music. And now our stage act was narrowing, and we were just doing more of that heavy rock and roll, which I love, don’t get me wrong [Music comes in].

That’s my riff. "I Don’t Need No Doctor." That’s me jamming at a sound check in Madison Square Garden. And Steve just jumped up on the stage and started singing "I Don’t Need No Doctor over that riff [More music]." He and I were very much—

Alec Baldwin: That’s him singing?

Peter Frampton: Yeah, yeah.

Alec Baldwin: He’s the one that says, ‘It’s been a gas!’

Peter Frampton: Yeah, we go home on Monday— [Steve talking]

Alec Baldwin: How old is he then?

Peter Frampton: Oh he was probably a couple of years older than me.

Alec Baldwin: Okay, so he’s still almost a kid. But you feel claustrophobic, why?

Peter Frampton: Because we weren’t—I wasn’t being able to do the music—all of this music that I wanted to do. Humble Pie started off really split between acoustic and electric. And also, I was coming into my own, and Steve and I fought like brothers.

Alec Baldwin: The Glimmer Twins.

Peter Frampton: Yes, that’s—which is why Humble Pie was so fiery, I think, because musically it was phenomenal. You know sometimes we’d agree, and sometimes we just wouldn’t agree. It was very sad for me, ‘cause I knew it would upset them. But I just felt that I had—it was time to go on.

Alec Baldwin: You left. Did you know where you wanted to go?

Peter Frampton: No idea. I knew that I was—I didn’t want to form another band. I wanted to be a solo artist at that point.

Alec Baldwin: You did?

Peter Frampton: Yeah.

Alec Baldwin: Why?

Peter Frampton: Because I wanted to make all the decisions, because I’m a complete control freak.

Alec Baldwin: But seriously, did you feel you wanted creative—you wanted more ...

Peter Frampton: Yeah. I wanted to try things that maybe other people wouldn’t want to try. I wanted to do it—and I have to say, that it wouldn’t have been—I wouldn’t have had a solo career had it not been for Humble Pie. I learned so much from working with Steve Marriott. I have to hand him a lot of the credit for the sort of things that he introduced me to listen to as well: music, Blues, and Bill Black Combo, and stuff like that, that was really influential to me. So, that’s why it was a bittersweet thing leaving. I wanted to leave, but I didn’t want to leave. And of course, as soon as I left, the live album that I’d had a big hand in mixing, because I’m the gadget freak and the engineer, with Eddie Cramer, "Rocking the Fillmore" comes out. I’ve left, right at that point. And it zooms up the charts. It’s Humble Pie’s first gold record. And I’m going, ‘Holy crap. That’s it.’ It’s the first big blooper of my career, you know. 'I’ve made a big mistake.’

Alec Baldwin: Seems like Dad’s back on the job.

Peter Frampton: Yeah.

Alec Baldwin: ‘Oh no, is he in the office again? I’ve Framptoned it this time.’

Peter Frampton: Absolutely. So then it was four studio albums before we did "Comes Alive." And a lot of touring.

Alec Baldwin: And where are you living then? You still haven’t moved here yet.

Peter Frampton: I was still living in England until ’75, when I finished the 4th solo record in England and then moved over. I actually moved to New York and stayed at the Mount Kisco Holiday Inn on New Years’ Eve in 1974.

Alec Baldwin: Swinging. Beautiful.

Peter Frampton: Yeah. And found Bob Mayo on keyboards from the live record, in the band at the Holiday Inn. It’s a long story. Yeah, so, basically first day of ’75, I was now living in America.

Alec Baldwin: When you do "Comes Alive," how much of the music on that is new music on the album, and how much of it was stuff you’d mined from the previous four solo albums?

Peter Frampton: It was basically all stuff that came from the four studio albums, and "Rock On from Shine On" was a Humble Pie track that I had written. It was actually from five albums. So it was like six years’ worth of work mining that went into that one live record.

Alec Baldwin: And for people who don’t know, that live performance was recorded in multiple locations, or in one?

Peter Frampton: Most of it was one location.

Alec Baldwin: Which was?

Peter Frampton: Winterland in San Francisco, a Bell Graham gig—where "The Last Waltz" was filmed. Two nights before we’d played the Marin Civic Center and we’d done two shows there. So we recorded that. I think a couple of numbers came from there. "Dooby War" comes from there and maybe one of the acoustic songs. But Winterland was the first big headline show we’d ever done—I’d ever done--with my name on the ticket. People were coming to see me, because the album right prior to "Comes Alive," just "Frampton" was the biggest one so far—biggest seller. It had sold like 300,000 copies, which was mega for me. That was better than all the others.

Alec Baldwin: So things—in that four-album run prior to the live album in Winterland, things were getting better. Sales were going up.

Peter Frampton: They were, but that one was definitely setting me up for something.

Alec Baldwin: How many nights at Winterland?

Peter Frampton: One. One show.

Alec Baldwin: Okay, okay, okay. So stop. So let’s cut the bullshit. Let’s cut the bullshit.

Peter Frampton: [Laughter]

Alec Baldwin: Let’s cut the bullshit. You’re in Winterland. And would you say, and the show goes on what time? 8:00? 9:00, 9:00? And a pre-act, and a warm-up act?

Peter Frampton: Probably a quarter to 9:00. Something like that.

Alec Baldwin: Somewhere between you pull up to Winterland and you go out a quarter to 9:00, the devil came in your room and made a deal with you, correct? You signed a deal with the devil.

Peter Frampton: Absolutely, yes.

Alec Baldwin: The devil showed up, poured himself a drink. Sat down, and said, ‘Peter, Peter, Peter, Peter. Let’s cut to the chase.’

Peter Frampton: It was Peter Cook, actually.

Alec Baldwin: It was Peter Cook, and he said ‘Let’s make a deal.’

Peter Frampton: ‘I’m the devil.’

Alec Baldwin: And the devil makes this deal with you, because what happened?

Peter Frampton: First of all, there’s probably—if I’m not mistaken, if there wasn’t 7,500 people out there, then I thought there was—but it definitely sounded like it. It’s a big room. They go nuts when we walk out. And it just takes you to a different level.

Alec Baldwin: It felt good.

Peter Frampton: It was one of those shows, when you come off and you look at the band and you just go, ‘I wish we’d recorded that. That was like, so good, man!’ And then we went, ‘We did!’

Alec Baldwin: You did record it.

Peter Frampton: We did record that. We forgot we were. You see, the event was so much more important than the recording. I don’t even remember the truck being there. [Music comes in]

Alec Baldwin: The recording is June of 1975 and it’s released when?

Peter Frampton: We’re still mixing right up before Christmas, and then it comes out I believe on like January 17 or something like that.

Alec Baldwin: Of ’76.

Peter Frampton: January 9 of ’76, yeah.

Alec Baldwin: And what happens?

Peter Frampton: Well, I knew we were gonna tour the whole year. So right after Christmas, I went down to the Bahamas for 10 days and relaxed. Before I left, we had put one show on at Cobo Hall in Detroit, which is a big room. And that’s all I knew. And so I go away. I don’t call anybody, I’m just on the beach. Snorkeling, whatever. I come back and we’ve sold four shows out. And I said, ‘What happened?’ And the album has just started to be on the radio, you know. And that’s when everything just went through the roof, you know. After all this time, people think it is overnight. But it’s not overnight in the scheme of things.

Alec Baldwin: No, no. It’s a huge leap for you.

Peter Frampton: Yes.

Alec Baldwin: But it’s not an overnight success.

Peter Frampton: But it is—it’s a heady experience.

Alec Baldwin: Is it still the highest-selling live album of all-time?

Peter Frampton: It’s in dispute.

Alec Baldwin: Right, right. But it’s up there.

Peter Frampton: Yeah, because my record is only counted as one album. Certain other artist had it made so that you could count—if you released 6 CD live set, you can count it six times. Well, they didn’t do that retroactively, so in my mind, it’s still the biggest seller, yes.

Alec Baldwin: And eventually, how many albums did you sell?

Peter Frampton: We’re up in the 17 millions now.

Alec Baldwin: 17 million records of this you sold. When you come out of that experience of having this huge thing, I want to talk to you not about how it affected you career-wise, because obviously that wasn’t important. How did it affect you personally? Were you married at the time?

Peter Frampton: I had a girlfriend at the time. I don’t think anybody can be ready for that kind of success. And I’m pretty down to earth person. I take things as they come. As I said earlier to you, I was a late bloomer when it came to dulling anything, you know. It was almost unbelievable the amount of success. You get these phone calls in quick succession. ‘You’re number one in the charts.’ And I’m going, ‘Wait a second. Say that one more time. And who are you?’ And then within three or four weeks of that, I get the call saying, ‘It’s the biggest selling record of all time. You’ve just outsold Carole King’s "Tapestry."’ And it’s—

Alec Baldwin: Was that the time you thought you had to start numbing yourself?

Peter Frampton: Yeah, it was crazy because people just wanted—

Alec Baldwin: You don’t know how to deal with that. You don’t know how to deal with how people treat you differently.

Peter Frampton: Exactly.

Alec Baldwin: How your life changes.

Peter Frampton: And being always respectful, and never really thinking of myself as anything special, because I’ve never been—that’s just not my character.

Alec Baldwin: And what good does it do you?

Peter Frampton: I felt embarrassed that I was that this entity that it became was me over here. Yes, it was very hard to deal with.

Alec Baldwin: But were you proud of the record?

Peter Frampton: Oh my god, yeah. I’m still proud of the record.

Alec Baldwin: ‘Cause it’s one thing when people become famous and have a—regardless of the ramp up, regardless of all the years before, regardless of the whole timeline of their career, and then they have some seismic event like that, and they don’t really deserve it. In your case, you’re great. I mean, you really are phenomenal. But aside from your own gifts, who helped really really make the record roll out that way? Jerry?

Peter Frampton: Jerry def—well, I have to say, Jerry and Herb for sticking with me as long—they stuck with Humble Pie too. They stuck with Police. Well Police happened pretty quickly, but there’s a lot of acts in those days that—

Alec Baldwin: Needed nurturing.

Peter Frampton: Needed nurturing. And it was like a club. You come over here. And Jerry and Herb never told us what to write or what to record. They let us do our thing and find ourselves. And I have to say, Dee Anthony, the manager, was a great promoter. He wasn’t terrific with finances, but—especially mine, and then Frank Barcelona, the agent. If you weren’t with Frank, you weren’t anybody. That was premier talent.

Alec Baldwin: Who else did he handle?

Peter Frampton: Everybody. Springsteen, Led Zeppelin. I mean, everybody. The Who, the lot. Everybody.

Alec Baldwin: Did that plague you at that time about finances? Did you find that you didn’t get what you thought was fair?

Peter Frampton: Well, I was ripped off. But I would go back and talk to Bill Wyman because he’s sort of like my mentor, my older brother. He said, ‘Ah, we all get ripped off. Stones, The Beatles, we all got ripped off. Then you learn, and you go and do it again.’ I tell you why it happens. It’s because I’m a musician. I’m a creative person. I’ve never done what I do for money. I’m stupid when it comes to money, you know.

Alec Baldwin: You left a lot of money on the table.

Peter Frampton: Yes. So I trusted people to look after things for me. And they didn’t. They took it.

Alec Baldwin: Did that change after you had the number one selling album in the world?

Peter Frampton: Well, that’s when it happened. That’s when it started. And some people it’ll happen to over and over again. But I have a team now that I wish I had then, obviously. And I’d become, I actually tutored myself in math a little bit after that. No, but it’s, you know what I mean—I have to blame myself as much as I blame everybody else.

Alec Baldwin: You must want to believe, as I do, that I couldn’t do—you might not have been able to do the work you did, on the level you did, if your mind was on something else.

Peter Frampton: When something really big hits in the entertainment business, it’s like feast or famine. It’s either not a hit, movie, record, whatever and nothing comes in, or it’s like a blockbuster and all this money comes in, and it all comes into one place, and when you see a pile of money likes this, it brings out thoughts that people didn’t normally have before. You know what I mean? It’s the availability of all that cash, all at once.

Alec Baldwin: Well, and especially in the music business. Because there’s nothing like the music business for making money.

Peter Frampton: Except for the fact that music is free now.

Alec Baldwin: Well, it is different now, yeah.

Peter Frampton: I mean, you used to tour to promote the record.

Alec Baldwin: And now?

Peter Frampton: Now you make the record to promote the tour. The record is a giveaway. The CD is a giveaway.

Alec Baldwin: The dollars are in the live performing.

Peter Frampton: Yes.

Alec Baldwin: That’s how it is for you.

Peter Frampton: Well, yeah—

Alec Baldwin: And most artists.

Peter Frampton: Yeah, and luckily my reputation is as a live performer, so it’s been phenomenal for me, but it’s hard work—touring, but I love it, so that’s not hard work for me.

Alec Baldwin: You came into New York recently, and you did that at the Beacon, here in New York. And how many shows did you do?

Peter Frampton: For most of 13 months, we were doing 5 shows a week, and it’s a 3-hour show. So we were doing "Comes Alive" first, which is an hour and 40. Then we were doing excerpts from everything else in my career as well for another hour and 15 or 20. So it was—we were killing ourselves.

Alec Baldwin: How did it feel?

Peter Frampton: Well, it felt great. The first show we did was in New Jersey—

Alec Baldwin: The first time you did "Comes Alive" concert-style.

Peter Frampton: Yes. First time we’d played it since ’76.

Alec Baldwin: Okay.

Peter Frampton: And the second show was the Beacon. The place went nuts. They just went berserk.

Alec Baldwin: Are you gonna do it again?

Peter Frampton: I don’t know whether I’ll do the entire thing again.

Alec Baldwin: Would you do "Comes Alive" again?

Peter Frampton: Not for a while anyway.

Alec Baldwin: Goddamnit!

Peter Frampton: No, no, we filmed it.

Alec Baldwin: You did film it.

Peter Frampton: Yeah. At the Beacon and in Newark.

Alec Baldwin: Where is that going?

Peter Frampton: It’s going to be DVD. In fact, that’s where I’m going on Sunday to go back home to my studio to mix the audio.

Alec Baldwin: What are you going to do with it? Are you going to release it as a DVD or as a film in theaters, or on TV?

Peter Frampton: No. Probably just be a DVD.

Alec Baldwin: You don’t want to do this on TV?

Peter Frampton: Oh, I’d love to, yeah. Have you got an in there, maybe?

Alec Baldwin: Oh, I can’t believe--if it’s a documentary—are there any backstage footage?

Peter Frampton: I’ve got the story and it’s filmed of when my guitar was returned.

Alec Baldwin: What happened to that guitar? What’s the story?

Peter Frampton: Well, first of all, we’re talking about the guitar that’s on the front cover of Comes Alive, which I got given to me by Mark Marion in 1970 when I was playing the Fillmore West with Humble Pie. And I was having a terrible time with the guitar I had that night, and Mark said to me, ‘You know, I can see you’re having problems with that. Do you want to try my Les Paul tomorrow?’ I said, ‘Well, I’m not really big on Les Pauls, but okay. All right. Anything’s better than this.’ So he brought it to me. I played it. I don’t think my feet touched the ground the entire night. It’s the best guitar I’ve ever played.

Alec Baldwin: A ’54 Les Paul.

Peter Frampton: A ’54 Les Paul. So then I played that guitar on "Rock On," and also "Of Humble Pie," and also "Rockin’ the Fillmore." And that’s the guitar I used on there. Basically I used that exclusively, it’s the only guitar I play all the way through all my solo records, including "Frampton Comes Alive."

Alec Baldwin: And you were never tempted to put that down and that was it. You married that guitar.

Peter Frampton: Yes. It was just this one—I had a ’55 Strat that I would always use for "Show Me The Way," ‘cause I needed a cleaner sound. So that was on "Show Me The Way." So then we get to touring South American in 1980. We just finished playing Caracas, Venezuela, and we had a day off. So we flew commercially to Panama waiting for the gear to arrive on cargo plane. Well, it never got off the runway in Caracas. It crashed on takeoff. My road manager came to me, I’m having this huge meal on my day off, with my wife at the time. And he said, ‘I’ve got some bad news.’ And he says, ‘The plane crashed on takeoff.’ I said, ‘My guitar?’ He said, ‘Mm-hmm. And like 6 people—loading people, the pilot, co-pilot, loading inspector, all that.’

Alec Baldwin: They were killed.

Peter Frampton: Yeah. Yeah. People died.

Alec Baldwin: Oh, how awful.

Peter Frampton: That took precedence over everything, and it put it in perspective. And there’s the pilot’s wife sitting at the bar who doesn’t know yet. It was horrendous. So anyway, we limped through the end of that tour with borrowed equipment. Sent someone down—my guitar tech at the time, a week later to see what was left. Nothing was left—supposedly. And what had happened—the tail had broken off. Guitars were actually in a trunk—

Alec Baldwin: In cases.

Peter Frampton: In cases, and the way the story goes is they had a guard to guard the crash site—the debris site until the insurance people came down. And he decided that the guitars would be much safer at his house.

Alec Baldwin: No!

Peter Frampton: Yes.

Alec Baldwin: In Caracas.

Peter Frampton: Yes, in Caracas.

Alec Baldwin: This is 1980.

Peter Frampton: 1980. Two years ago, which is 30 years later.

Alec Baldwin: 30 years later.

Peter Frampton: I opened my info at Frampton.com email, because anybody can email me. And I see them all. I open up this one, and there’s a picture—a photograph of my guitar, slightly singed, but— but it’s my Les.

Alec Baldwin: Nicely singed.

Peter Frampton: Right at the top, you know. Slightly singed. But there it is. There’s a picture, and I thought, ‘Could this be?’

Alec Baldwin: You see this picture where?

Peter Frampton: In an email to me from someone who’d got a hold of the guitar as it happens in Curasal—which is a little island off of the coast of Caracas. Someone had sold it to this gentleman and he took it to someone who fixed guitars, and they knew what it was. And it took two years of a very grey area.

Alec Baldwin: And was he saying, like, ‘I don’t wanna get—I want to get this guitar to you, but I don’t want to go to jail.’

Peter Frampton: That was the thing. No one wanted to actually come—

Alec Baldwin: It wasn’t about money. It wasn’t about him wanting—

Peter Frampton: There was money involved.

Alec Baldwin: He would have appreciated a gratuity.

Peter Frampton: There was a reward talked about. But every time it would get close to someone coming in, they’d find a reason they couldn’t come in. So that’s why it took two years. And then in the end, the guy actually checked to see if we had booked him a hotel. ‘Cause he just saw himself in handcuffs at Miami Airport. He knew who had it and the person who had it needed some money, so he went to the tourist bureau of Curacal and said, ‘Look, if you lend me the money—or give me the money to go buy this, I can find this. This will be a great tourism story for Curacal.’ And—

Alec Baldwin: They did?

Peter Frampton: And they did. And they came, and the two of them, the President of theTourism Board from the government, and the gentleman who found the guitar, who knew where it was, brought it to Nashville. We had 3 cameras as soon as he walked in—

Alec Baldwin: Waiting.

Peter Frampton: Waiting.

Alec Baldwin: And what happens?

Peter Frampton: Well, the two gentlemen walk in and he’s got it in this—probably one of the worst looking gig bags I’ve ever seen in my life. Cheap old plastic thing. He puts it beside him, and he tells the story in broken English of how this person had it, the whole thing. He hands it to me and he goes, ‘Feel it, Peter. Feel it, feel it.’ So, and I know that he knows because it was the lightest Les Paul I’d ever played. So I just felt it in the case and I went, ‘Ooh. This could be it.’ Opened it up, I just looked at it. And I just feel it like that, and I go, ‘It’s my guitar.’

Alec Baldwin: And how badly was it singed? Where?

Peter Frampton: Just round the very top. It lost the binding around the head stock.

Alec Baldwin: Did you get that replaced?

Peter Frampton: No. I didn’t. I left it—I’ve left it with its battle scars.

Alec Baldwin: Yeah, yeah.

Peter Frampton: Gibson made it playable. So we—

Alec Baldwin: We call that the Caracas kiss.

Peter Frampton: Yeah.

Alec Baldwin: On the tip there. Does it sound the same? Does it feel the same? It’s not damaged it at all?

Peter Frampton: Oh my god. No.

Alec Baldwin: Just that singe.

Peter Frampton: Yeah, and when I first played it at rehearsals with the band, everybody had this like Cheshire cat grin on their face, because it has this sound, and it sounds like "Frampton Comes Alive." You know, you don’t have to try too hard.

Alec Baldwin: You got that back when?

Peter Frampton: I got it back just before we started touring in February and March for the last American leg. I used it a little bit at rehearsals and then I brought it out for the first night of the Beacon. I think the guitar is more famous than I am now. So—

Alec Baldwin: But you were meant to play that music with that guitar. Isn’t that incredible?

Peter Frampton: I remember saying to someone that, before I went out that night, I just hope emotionally I’m going to be able to play it, and I brought it for "Do You Feel." And I messed up the first lick because I couldn’t believe I was playing it. How can you fumble, da der da der. Me, I did.

Alec Baldwin: Well, it’s okay.

Peter Frampton: It was like meant to be. Once I got—it was saying to me, ‘C’mon, get it together. Yes, I’m back, now get over it.’ [Music comes in]

Alec Baldwin: Peter Frampton has just completed his 35th anniversary tour of "Frampton Comes Alive" and says he plans to release the DVD this fall. In addition, to celebrating his past, he’s also busy with new projects, including a collaboration with the Cincinnati Ballet which will debut next spring.

Alec Baldwin: What music do you listen to now? Who do you like?

Peter Frampton: Right now this week, Band of Skulls. My son turned me on—and daughter turned me on to them. I went to Coachella and saw Radiohead. I still am a Radiohead fanatic. I just love them. I think they’re so not mainstream, but they became mainstream because they’re just so unique. It was an eye-opener for me to go to Coachella with my daughter, who’s 16 and just have fun.

Alec Baldwin: This is Alec Baldwin, you’re listening to Here’s the Thing from WNYC Radio, and if you haven’t figured this out by now, I am one of Peter Frampton’s biggest fans.

[Music]

Alec Baldwin: Here’s the Thing is produced by Emily Botein and Kathie Russo, with support from Jim Briggs, Brian Cosgrove, Wendy Dorr, Ed Herbstman, Melanie Hoopes, Monica Hopkins, and Ariana Pekary. Thanks to Larry Josephson and the Radio Foundation. Here’s the Thing comes from WNYC Radio.

Alec Baldwin: You know I haven’t said this to many people who’ve come and done this show, but I can’t thank you enough, because your music is so important to me.

Peter Frampton: Oh, thank you.

Alec Baldwin: I mean, I have listened to you and I have loved your music and your playing for so long, I mean it’s such a part of my life that I really want to thank you. You are a great, great, great musician.

Peter Frampton: Well you’re very welcome.

Alec Baldwin: Thanks.