Lost Cause

(Distorted music begins, as if playing backwards, then stops suddenly.)

Tracie Hunte: I don’t know a lot about the South, even though I’ve geographically lived in the South for so much of my life. As I tell people, Miami is geographically the South. It is not southern. (Laughs.)

Julia Longoria: It’s a whole other thing. (Chuckles.)

Hunte: It’s a whole other thing. (Laughs again.)

Longoria: I’m Julia Longoria, and today, we’re hearing from correspondent Tracie Hunte, who—like me—grew up in Miami, Florida.

Hunte: My high school was 99 percent Black, but we had a white AP-history teacher. I can’t remember her name. I just remember that she always had, like, a really nice manicure. She had, like, those long nails and [Laughs.] she had the most beautiful cursive writing.

But I remember when we got to the Civil War unit in our American-history class, she was like, “Okay. First of all, there are people who are going to tell you that the Civil War had nothing to do with slavery. That is a lie.”

(Slow, quiet guitar music plays.)

Hunte: “It absolutely had something to do with slavery. They’re going to talk—they’re going to blame it on states’ rights; they’re gonna blame it on heritage. No, that is not true. It absolutely had something to do with slavery.”

And I remember just sitting there, being like [The music wavers for a moment, then rewinds suddenly.], Duh! Like—like, why is she telling us this? (Hunte and Longoria laugh.)

(The music resumes.)

Longoria: Like, “What are you talking about?”

Hunte: Of course. Like, “What are you talking about?” And it was decades, like—not decades—but it was a while later until I finally heard about this thing called the “Lost Cause” myth.

(A moment of quiet music.)

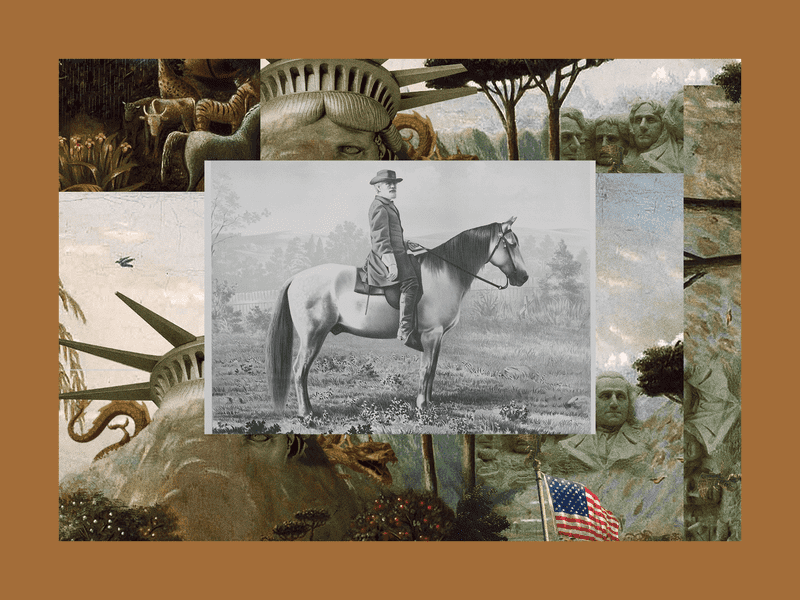

Hunte: The Lost Cause myth is this idea that the Civil War, at least from the point of view of the South, had nothing to do with slavery. That it was about states’ rights, that southerners were just trying to protect their way of life, that they fought honorably and righteously—they were trying to protect their families from this war of northern aggression—and that Robert E. Lee, who was the head general for the Confederate armies, was the most perfect gentleman. He didn’t even want to fight the Civil War, and it tore him up inside to be doing this.

And, oh, by the way, slavery wasn’t even that bad! And enslaved people in the South were treated well by their masters, and they were loyal to their masters. And that they even fought alongside the Confederates.

Hunte: It’s a way of buffing and smoothing out all of these ugly realities of what slavery actually is into this glossy Gone With the Wind myth.

Longoria: It’s like that’s easier to believe …

Hunte: Right. Yeah.

Longoria: That’s easier to believe than to think, like, such horrible, horrible inhumanity happened.

Hunte: Right. And, you know, I’ve been thinking about the Lost Cause lately because, on January 6, we saw Confederate flags in the Capitol. And that was truly shocking. And then, a couple of weeks later, I was scrolling on Twitter, and I was really struck by this video.

Jeff Glor: This morning, as we continue our focus on the most-interesting new books …

Hunte: CBS was interviewing this guy named Ty Seidule. He had been in the military for about 30 years. He taught history at West Point, and he had just retired.

Glor: —he says, so he could finally speak his mind in full.

Hunte: And he’s talking about how he grew up in the South, and had grown up believing in the Lost Cause, and how Robert E. Lee was his hero—until one day he had this revelation that Robert E. Lee was a Confederate traitor.

Ty Seidule: He was a cruel enslaver, someone who believed deeply, firmly, and really his entire life that human enslavement was the best social system for the South.

Glor: The result of that work? His new book, Robert E. Lee and Me.

Longoria: And how old was he when he had this revelation? Did you get a sense?

Hunte: He was, like, 40 years old, and had a Ph.D. in history.

(Ethereal ringing music plays.)

Longoria: So why did you want to talk to him?

Hunte: So many people are talking about disinformation, you know, right now and whether it’s QAnon, whether it’s believing, like, the president really won the election … You know, all these weird conspiracy theories. And we sort of talk about it in this way like it’s—it’s a new thing. But, you know, the Lost Cause myth is nothing if not, like, a huge disinformation campaign. And so we’ve—we’ve—we’ve been here before. [Laughs.]

And we also know that it’s really hard to have a functioning democracy when significant portions of the country can’t even agree on, like, basic facts.

And one of the most basic facts is “Why did we fight the Civil War?”

(A moment—a breath—of music.)

Hunte: And so,if that’s the case, then, we have to get a lot of people—white people—to, like, wake up and just admit the Civil War was fought because of slavery.

(Music fades down.)

Hunte: How do we get white people to just get on the same page?

Longoria: And here was a white person who, like, went through the process.

(Music comes back.)

Hunte: Who had done it. Yeah.

Longoria: This week, Tracie Hunte has a conversation with a man who believed a lie about America for most of his life. She tries to figure out what it took for him to give it up … and what it would take for others like him to do the same.

This is The Experiment.

(The music crescendos, then cuts out.)

Hunte: Hi. Uh, Mr. Seidule?

Seidule: Hello?

Hunte: Oh, hi! Hello. Um, thank you so much for doing this ... (Fades out.)

Hunte: Ty Seidule grew up in Alexandria, Virginia, where Confederate symbolism was everywhere. It was a big part of his childhood. In his home, there were these, like, four flags of the Confederacy hanging above the mantle. And Robert E. Lee, specifically, was everywhere: streets named after him and statues of him.

Seidule: I can’t remember life without Robert E. Lee.

What I grew up with was this omnipresent idea of “gentleman.” And now, when I thought of him growing up, it was “gentleman” that really made me think of Robert E. Lee. And that—that encompasses not only the way he looked, but the way he acted. So every aspect of my life made him the hero. And so I would say that, you know, on a scale of one to 10, Lee was an 11!

And even though I was a good Episcopalian—went to church every Sunday—I would have put Jesus at the four-five-six range.

Hunte: Which would be shocking to Jesus, I think. [Both laugh.] Uh, I guess … That is, like—that’s wild to me, you know? And so … you talk about Robert E. Lee being a gentleman. Like, what does that mean?

Seidule: So what gentleman meant to me was status. So in—in the world I grew up with, you would talk about white men of a certain socioeconomic class that had education, that treated everyone well: That would be status.

So I thought of it as being good manners—uh, holding the door open, uh, for women when they went through. It was holding the chair out. It was learning the social etiquette of the time. So it was very linked to what I wanted, which was status and power.

Hunte: So when you got into, like, middle and high school, you know, I’m assuming that y’all started talking about the Civil War at that point. What were you told about why the Civil War happened?

Seidule: (Stammers for a moment.) Nothing, uh, that I remember. I don’t ever remember looking at that. And I really didn’t think about what it was fought for, ’cause what I concentrated on was, like, Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg, leading the fight on day three. How bravely they went into sure disaster. How bravely they fought. All these things. And this is part of that Lost Cause mythology.

So, even as I learned later in life that the Civil War is about slavery, it still allowed me to do Confederate idolatry, to worship Lee as a man who did what he had to do, did it well, and then helped the country to come back together. That’s what I learned.

Hunte: Ty was fed a story. And this story was so powerful that it allowed him to ignore how it might have been for other people growing up in the South.

Seidule: I remember, in the sixth grade, I was actually bused across town from the white elementary school, and I was going to go to the segregated all-Black school. And what was the name of that segregated Black school? It was Robert E. Lee Elementary School.

And I was so excited and—and my other—the other kids were going, we were going to school! And I went to this school named after my hero, named Robert E. Lee Elementary School. It was all-Black segregated school, named in 1961 as a reaction to integration. And when I was there, we had—the school was actually shut down several times for bomb threats. Other schools had crosses burned on the front lawn. And—and it started a white flight in Alexandria, where kids moved away from this integrated learning.

Hunte: But Ty didn’t see the connection between the Lost Cause and the racist violence and segregation that was happening around him. Even going to a segregated school, and later being moved to an all-white private school, didn’t make him question this myth. And when it was time to pick a college, he decided to follow his hero.

Seidule: My first choice was where I went to college. And, uh, where I went to college was to be a Virginia gentleman. And what is the best way to do that? Go somewhere named after the two great heroes, the two great gentlemen of Virginia: Washington and Lee.

And for me, it was walking into Lee Chapel, the first day I was there. So when I went in there, you know, you would think, Oh, there’s a pulpit. There’s a little place where the hymnals are listed. There’s … You know, all these different things that go along with the church.

But on the altar, this white slab of marble, lay a statue of Robert E. Lee in repose. So, in other words, his white marble, lying on the battlefield with a blanket covering not his boots, with his hand on the sword, ready to rise up to fight for the white people of the South.

And it was surrounded by Confederate flags. So that was my education. We went and we worshiped literally at the feet of Saint Bob. And he was buried right below there.

Hunte: He’s buried below the chapel?

Seidule: Yes, he’s buried below the chapel. And right next to him is his horse Traveller. And they still leave carrots and apples there on Traveller’s grave, and they also put pennies on that for him, always face down.

And for two reasons, Tracie. They put it down for two reasons. The first is so that Lincoln’s head won’t be visible to the great Robert E. Lee. And so that Lincoln will have to kiss Traveller’s ass.

Hunte: That is …

Seidule: Awful. Wouldn’t you say?

Hunte: I was going to say “bizarre,” ’cause I—I think that’s what I keep coming back to, is that it’s just so … You know, I think the cultishness of it, and the religiosity around it, is what’s really kind of alarming to me.

You know, I love that part in the book where you talk about your wife, who’s Catholic—or grew up Catholic, I don’t know if she’s Catholic anymore—but she comes into Lee Chapel, and she’s immediately like, “Get me out of here. This is crazy.” Because she automatically just saw that what was happening was that Lee was being worshiped as a god.

And I’m wondering, when—when she said that, did you realize that?

Seidule: So my wife didn’t grow up learning to lie like I did. You know, my entire being, almost, grew up with these lies of the Lost Cause and—and white supremacy. And I wish I could tell you—I really wish that I could tell you that when she said that, I saw it.

But I didn’t. I still didn’t see it.

I still saw … You know, this was my school, and she was trash-talking my school and my way of life. And she totally was [Laughs.] because—she totally was—because we deserved it!

Hunte: For good reason. Yeah.

Seidule: For damn good reason!

(Soft string music plays.)

Hunte: After college, Ty went into the Army. He got a Ph.D. in history. He served abroad. He has all these different experiences outside of the South. But it would be another 20 years before he would finally see that much of what he grew up with—his culture, his heritage, the people and history he was told to be proud of—that it was all based on a big lie.

By the early 2000s, Ty had spent 20 years in the U.S. Army and was teaching history at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. It’s the top school for training military officers. And one day, he said he was just walking around campus when things suddenly, somehow, stopped making sense.

Seidule: You know, now I am fully—I’m a soldier and I fight for my country. I have fought for my country in war and peace. And I’m living on Lee Road, and I go walking one day. And I walked by Eisenhower Barracks, Pershing Barracks, Grant Barracks. Naming barracks is our highest honor at West Point.

Hunte: The Barracks at West Point, like a lot of dorms at universities, are named after old dead men. Military heroes like General Pershing from World War I, General Eisenhower from World War II, and General Grant on the Union side of the Civil War.

Seidule: And then I get to Lee Barracks. And I look at this sign, and it says Lee Barracks. And I just stopped there, just staring at it. And then I look east about 20 yards, and they put up a new memorial to Lee in 2001. I was living in Lee Road by Lee Gate in Lee Housing Area. “Why are there so many things named after Lee here?”

I mean, I understood Washington and Lee, but I didn’t get … [Incredulous.] The United States Military Academy has all these things named after Lee?! What the hell?

Hunte: And why is that weird? Why would that be weird?

Seidule: Well, because that’s when I finally figured out: “I mean, wait a minute! This guy didn’t fight for the home team. He fought against the home team. He didn’t fight for the United States of America. He fought for the Confederate States of America.”

So this was—the epiphany was “Wait a minute. He didn’t fight for us. He fought for the bad guys.” And now I see this, and I go running all over campus. And I find more than a dozen things named after Lee.

(Soft, fluttering music plays.)

Hunte: Up until that point, the name Lee had always felt like a home to him. But seeing it there, beside the names of other victorious generals in American history—seeing the name of someone who lost—that image he held of Lee as an American hero just suddenly looked out of place. And it made him wonder how it got there in the first place.

Seidule: And that sent me to the archives.

Hunte: So, before the Civil War, Lee had actually been the superintendent at West Point. But when he resigned from the U.S. Army and joined the Confederacy, he became a traitor.

Seidule: And what I found in the archives was that West Point banished the Confederates up until the 20th century.

Hunte: After the war, Lee thought he would be hanged for treason. But that didn’t happen. There were calls to unify the country, and he got a pass. And that’s when his rehabilitation started. He went on to become a university president. And in 1931, his name starts popping back up at West Point. They started giving out a math award named after him. And Ty wondered, Why had West Point changed their minds about Lee?

Seidule: In the 1930s, that’s when the first African American cadet graduates from West Point in the 20th century: Benjamin O. Davis Jr., later leader of the Red Tails in World War II, Tuskegee Airmen, later the first four-star general in the Air Force. I mean, he was—this is a great hero.

But when they bring Black cadets, that’s when they name things after Lee. And in 1952 is when the army is fighting against integration. That’s when they bring a Confederate portrait of Lee. And in 1970, when they name the barracks, that’s a year after they start the minority-admissions program, and we go from a handful of Black cadets to dozens of Black cadets. So at every turn, I find that “When did they name things after Confederates?” is as a reaction to integration.

And that just tore me up—tore me up! I start seeing this link between Confederate memorialization and what the Confederates did themselves. There’s no difference. It’s all about racism and white supremacy.

Hunte: Did you feel like you had been duped?

Seidule: Part of it was duped, and part of it was my own, um, asinine ignorance and stubbornness, not to see the facts right in front of my face.

Hunte: I want to know: Why did it take you so long?

’Cause I look at you, and I’m like, “You went to the best universities. You had the best education. You’re, like, you know—you just—you’re—you’re a history professor, for crying out loud!” (Laughs.)

Seidule: Yeah.

Hunte: Like, what was—what wasn’t … Yeah, I’m just going to say it: Why?

(A wistful, almost dusty instrumental track plays in the background.)

Longoria: The answer to “Why?” after the break.

(The music plays for a moment longer, and then the break.)

(Rewinding musical flourish.)

Hunte: I want to know: Why did it take you so long?

Seidule: Why was I such a dumbass? I mean, that is really—it is really the crucial …

Hunte: Sure. [Laughs.] Okay.

Seidule: And yeah, I know! Let’s just put it on there.

Hunte: So this is what I wanted to know. Why did it take so long for a history professor with a Ph.D. to see that the Lost Cause was a myth, a lie. Why did someone with all of the training, all of the facts, just not see the truth?

Seidule: You know, the thing is that history is dangerous because it creates your sense of identity.

I mean, I taught, when I was at West Point, I taught that the Civil War was about slavery. It wasn’t as though I didn’t teach the facts. But somehow I could still revere this person that meant so much in my life.

And that—that was my sin, not looking at that carefully enough. The other part is that I had been wearing “U.S. Army” over my heart for over 20 years.

(Quiet, serious music plays.)

Seidule: I took the oath.

Master of ceremonies: I do solemnly swear.

Army cadets: Do solemnly swear.

Seidule: And the oath that I took, that we—everybody—in fact, everybody in Congress takes …

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi: Do you solemnly swear that you will support and defend the Constitution of the United States?

Army soldiers: (In unison.) I will support and defend.

Representative Dean Young: The Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic …

Seidule: That oath was written in 1862 as an anti-Confederate oath.

Speaker Pelosi: … against all enemies, foreign and domestic.

Army soldiers: (In unison.) Foreign and domestic! (This call-and-response continues, hushed, under narration.)

Seidule: When it says, “Defend against all enemies, foreign and domestic, ”when it says, “No purpose of evasion”? Those are talking about Confederates.

(Slightly eerie music plays.)

Army emcee: And do you bear true faith and allegiance to the same?

Vice President Kamala Harris: (Picking up where the Army emcee left off.) … the same. That you take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion.

Seidule: And so my identity had changed over that time.

Army emcee: And I will obey.

Army soldiers: (In unison.) And I will obey!

Army emcee: The orders of the President of the United States.

Army soldiers: (In unison.) The orders of the President of the United States!

Seidule: My identity was no longer “southerner.” It was no longer “Virginian.” It was no longer even “gentleman.” It was “U.S. Army officer,” which was very important to me. And when I saw that “Lee” in my home of West Point and the United States, that said, “Wait a minute!” That—that’s what the epiphany was, because I identified now as an American, not as a southerner.

Vice President Mike Pence: Do you well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office upon which you’re about to enter, so help you God?

Army emcee: … about to enter, so help you God?

Army soldiers: (In unison.) So help you God.

Army emcee: Acknowledge the oath.

Army soldiers: (In unison.) I do!

(A moment of music, then quiet.)

Hunte: So you had to, like, go through a fundamental change in your identity.

Seidule: I did.

Hunte: That’s huge!

Seidule: It is.

Hunte: That’s a big thing. That’s not easy!

Seidule: No.

Hunte: So, like, part of the reason why I’m interested in this … Um, I don’t know if you Googled me. I’m Black. [Laughs.] Um … and I think about the fact that so much about what we have to do as a country is we have to move forward on race.

I feel like what we have to wait for is people like you—white people—have to, like, have these “aha” moments. They have to realize, you know? And that’s scary to me because [A beat.] like, with you, it took until you were 40. And so I’m just like … I’m just really nervous about having to wait for these moments.

And—and I—and I’m wondering what your reaction to that is. Like, how can we have a real reckoning, if what we have to rely on is individual white people to realize the truth in this country?

Seidule: You’re exactly right. And, in fact, it’s—it’s … I think it’s worse than you say, because after every moment of movement toward equality is followed by a white backlash that is more violent and more devastating than the last.

I mean, racism is so endemic to our country. I’m talking about the southern story, but racism goes from sea to shining sea.

Hunte: Oh, definitely. Yeah.

Seidule: I mean, this is not just a southern-only problem.

I mean, I don’t know what the answer is to that. All I know is, more white people have to accept the facts of American history. I wish I had a better answer of how we’re going to do that. I don’t know. I know, though, that it does require white people admitting where they come from and who they are, and then fighting like hell to end that.

(Lighter, slightly upbeat music plays.)

Hunte: It’s … Yeah, it is amazing to me, because—and you say this in your book—the South lost the war, but they won the narrative. And it’s actually kind of a counter to that old saying is, you know, “The winners write the history books.” But in this case, like, the—the losers actually wrote the history books.

(A breath of music.)

Hunte: One thing I was kind of surprised to learn about Robert E. Lee was that he was never punished.

And that after he declared war in the United States, he was able to have, like, a pretty good life. Got a really prestigious job, was well paid, you know. Had a whole university named after him after the Civil War. You know, Jefferson Davis apparently was in jail for two years and that was it.

And all of that happened in this desire to kind of unify the country and move forward after such a bloody conflict. Do you think things would have been different if Robert E. Lee had been hanged for treason?

Seidule: Well, I do know that there can’t be reconciliation without truth and justice first. And we did not get that.

I mean, remember, there’s only one crime in the Constitution: It says, “Levying war against the United States.” And no one did that like Robert E. Lee.

So I certainly wish that more people had been held accountable for that, because they certainly did not accept the results of this war. Would that have meant other white people would have accepted the results of the war? Doubtful. Doubtful!

I don’t think that the white South was ready. I mean, they showed they were going to execute political violence to ensure racial control, no matter what. But because we know that they weren’t, it means that we must hold people accountable today. And we must have justice, and truth before we can get to reconciliation.

(A long moment of music plays, synth-heavy and spacey.)

Longoria: So, Tracie, I wonder, what did you make of this conversation in the end? Like, did you get the answer you were looking for?

Hunte: Yeah. He was making the point that your culture is more powerful than what’s written in history books.

And that’s what he was holding on to, was his culture, at the end of the day. And, in a weird way, it kind of reminded me of that experience I had with my teacher, because I, being a Black woman—Black teenager at that time—my culture was very much like, “Yeah, the Civil War was fought about slavery.” [Deep laughter.] And I didn’t need to read, like, the secession papers to know that.

He did. He had to read them, but I didn’t. [Both chuckle.]

Hunte: And that does make sense. Because, like—especially the way a lot of history is taught—and he talked a little bit about this, where so much of his history learning in school was just, “Fact, fact, fact, fact, fact.” Like, dates and places and people, and “facts, facts, facts.” They weren’t stories.

And the Lost Cause is a story. In that way, it’s way more powerful than the facts that he was being given.

Longoria: I mean, do you think about this moment we’re living now? Like, we saw this act of violence on January 6. We saw people attacking our government—our country—in a very blatant, visceral way that we watched on TV, and people died. And there was a lot of Confederate symbolism in the attack, like, displayed.

And almost immediately, we saw myth-making about it. The most extreme version is the sort of the QAnon-conspiracy version of the story, which said that these people were actually heroes who were trying to save our country from evil, and that Donald Trump was actually directing these people in a battle to save the soul of the nation. I mean, in light of everything you talked about with Ty Seidule, what do we do now to make sure that that story doesn’t win in the history books?

Hunte: His point was that we can’t have unity without some sort of accountability. And that there has to be some sort of 9/11 commission-type thing for January 6 … which I agree with. And then I guess, you know, we have to make a story about it.

And, I mean, you do see a little bit of that story thing happening. Like with the officer—I think his name is Eugene Goodman—a Black officer. It was, like, one of the most shared videos, was of him outside the Senate chambers. He runs up the stairs; he knows that there’s a mob chasing him.

(Soft music plays.)

Hunte: And when he gets to the top of the stairs, you see him looking to the left, and to the left is where the Senate chambers are. And so when the mob comes up, he runs right. And then the mob chases after him. And so, basically, he led the mob away from the Senate chambers. And it was scary and powerful, because you also realize that he’s literally using himself as bait, because he knows that these people will definitely chase a Black police officer to do harm to him.

So you see a little bit of … I wouldn’t say myth-making, but a little bit of, like, a story about him happening, where this Black man is the hero of that day, instead of Trump being the hero of the day.

(Another moment of music.)

Hunte: Is it enough? I don’t know, but … but I feel like there has to be facts, and there has to be a better story.

(A long moment of music.)

Matt Collette: This episode was produced by Tracie Hunte and me, Matt Collette. Editing by Julia Longoria, Alvin Melathe, and Katherine Wells. Fact-check by William Brennan. Sound design by David Herman. Music by Tasty Morsels.

Our team also includes Gabrielle Berbey, Emily Botein, and Natalia Ramirez.

Special thanks to Adam Serwer, Vann Newkirk, Veralyn Williams, and Jenisha Watts.

The Experiment is a co-production of The Atlantic and WNYC Studios. Thank you for listening.

(The music crescendos one more time before slowly fading out.)

Copyright © 2021 The Atlantic and New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.