EPISODE 6: On the (Camden) Waterfront

( David Lewis / WNYC )

Nancy Solomon: About two months after his parents were killed, Mark Sheridan needed to file their taxes.

Mark Sheridan: I asked, uh, the Somerset County prosecutor's office for all of the materials that they had taken from the house, copies of whatever they had.

Nancy: And what they gave Mark surprised him. It was enough to fill a banker’s box.

Mark: when I got back to the files from the Somerset County prosecutor's office, all of the L3 documents were there,

Nancy: L3. It’s an office complex on the Camden waterfront. The documents were all about the sale of those buildings.

Mark: And I'm trying to get my arms around it. And I start to see that from those emails, that there was a fight over this issue over this property.

Nancy: Mark knew about this because his father had asked him for legal advice about it five months before his death. His dad was upset about the issue back then. But the bankers box had more documents – and details – that Mark hadn’t seen.

Mark: They taken everything on the dining room table, essentially. And so, when I started looking through all of that, I was stunned to see those documents out and about in September of 2014.

Nancy: But there the documents were, on the dining room table the, night his parents were killed. Mark had discussed this real estate deal with his father. He knew how stressed he’d been about it months before.

Mark: And I know that this is what my father was upset about.

Nancy: There were handwritten notes about phone calls and meetings. Email exchanges that were printed out. And everything was dated. I called Mark recently because I wanted to know if this was typical for his father.

Mark: He was always, had a notepad in his hand when he was on the phone, uh, the full recitations of phone conversations and, uh, follow-ups, uh, is something I've never seen from him before though.

Nancy: Do you think it's fair to characterize it as a paper trail?

Mark: It definitely looks like a paper trail. Absolutely.

Nancy: I’m Nancy Solomon. This is Episode 6 of Dead End. We’re going to dig into those documents connected to those buildings on the Camden waterfront – to find out just what kind of paper trail this was, and why this real estate deal matters. To John Sheridan, to his boss, George Norcross, and to Camden.

There had been a lot of questions raised about the way the Camden waterfront was being developed. But I didn’t understand John Sheridan’s connection. That story starts in 2013 when then Governor Chris Christie signed the Economic Opportunity Act. It was a bill that supercharged New Jersey’s corporate tax break program.

Chris Christie: So with this act we’ll achieve even more as we encourage more companies to create jobs, to boost our economy and to help our cities thrive, which is a very important part of the goal of this legislation as well.

Nancy: Sounds like a noble enterprise. State tax breaks for companies that move to struggling cities in New Jersey. And that’s certainly Camden. The language in the bill included special benefits to a business moving there. Unlike most tax break programs, there were no requirements to create jobs for Camden residents. And the tax breaks were beyond generous. Here’s how they work. Say you spend a million dollars – on a building in Camden. You’d get a million dollar tax break. And you can actually sell that tax break – it’s really called a tax credit – for cash. Essentially, a business gets a dollar-for-dollar match on what it costs them to construct a building. Or renovate one. Or to cover their rent for 10 years. It’s a free buildings program.

The bill was sponsored in part by Donald Norcross, a brother of George. He was a state senator at the time, and now he’s a member of Congress. And sections of the bill were written by lawyers at the firm led by a third brother, Phil Norcross.

Jeff Pillets: It's a perfect setup.

Nancy: Jeff Pillets is an investigative reporter who has been watching the political players in south Jersey for decades.

Jeff: Perfect set up for a businessman. My brother writes the legislation. Me and my business partners buy up the properties. And pretty soon, my company and my business partners get $245 million worth of tax breaks, which allow us to build these beautiful buildings on the waterfront.

Nancy: Which we're looking at right now.

Jeff: I mean, you sit here and you've got the bridge, you've got the river, you've got Philadelphia, you've got a beautiful breeze blowing here.

Nancy: Jeff and I are sitting on a park bench by the Delaware river. When Jeff was a reporter at the Bergen Record, he spent a year researching George Norcross and the government insurance contracts he holds. But Jeff’s story was shelved after Norcross's legal team threatened to sue the newspaper.

Jeff: It's easy to say that he controls things, but it's hard to see the fingerprints and uh, but they do exist. We’ve seen them. And when you do see them, it's a stunning thing.

Nancy: In 2019, Jeff and I worked together on a series about the tax breaks on the Camden waterfront. Back then, this stretch of riverfront was a giant construction site. We met up to see how it looks now.

Nancy: So it's, 11 Cooper residential complex.

Jeff: 11 Cooper residential. That's the apartment buildings, right.

Nancy: There's the Camden Tower, that's George's office building.

Jeff: George Norcross’s insurance company and as well as his two partners have their companies in there and then over here, to our left here, which is off the water is, uh, the L3 building, which we know a little bit about.

Nancy: The state owned L3. It was built in the 90s. And it looks like a bland office park: two buildings, each three stories high, and made of brick. In 2014, the generous tax breaks for Camden were just going into effect and L3 was a one-of-a-kind opportunity. Unlike most buildings in Camden, it was ready for a business to move in, obtain a tax break for doing so, and get its rent paid for 10 years.

Jeff: Nobody was interested in these buildings for years, for decades. Nobody gave a darn about these buildings down here. But all of a sudden they're these buildings are maybe valuable because of the tax breaks.

Nancy: And nobody knew that better than the local business group that had been trying to improve Camden for decades: Cooper's Ferry Partnership. It’s a non-profit like most towns have, like a business improvement association, or a main street alliance. For 30 years, Cooper's Ferry has been the primary recruiter of real estate development in the city. They found developers for Camden’s aquarium, and for the baseball stadium. Cooper's Ferry knew about the generous tax breaks coming to Camden. And there was L3 – a block from the river, with parking, a cafeteria and a gym.

And here’s where John Sheridan comes in. He was the CEO of the hospital, the city’s largest employer. A big part of his job, and the reason he went to work there, was to work on improving Camden. And one of the ways he worked on Camden was by serving as chairman of the board of Cooper's Ferry Partnership.

The small nonprofit saw an opportunity. If the organization bought L3, they could use the profits from the rent to fund parks, or farmer's markets or other community projects. One analysis suggested that could be as much as 4 million dollars in the first 10 years. With Sheridan’s guidance, they signed a deal with the state to purchase L3.

And that brings us back to the documents left on the Sheridans’ dining room table. They show what happened when Phil Norcross, George’s brother, learned about the deal.

In an email dated January 27, 2014, the head of Cooper’s Ferry, the non-profit, wrote to John Sheridan, the chair of his board: "Just a heads up, Phil called and asked that I speak with him tonight."

Six weeks later, the head of the non-profit reaches out again to John Sheridan about the L3 deal. First he forwards an email from Phil Norcross, where Phil expresses an interest in the buildings.

Making an appeal for help from his chairman of the board, the head of Cooper's Ferry adds a note: “John, as you know, we do believe we can do this on our own. We would be interested in the right partner, so I will need your help in navigating these waters.”

What he's saying is, he needs John’s help fending off the possibility that the Norcross brothers will insert a partner of their choosing, or take over the deal altogether.

The CEO of the non-profit then adds: “I am okay with a conversation, but don’t want to lose out on the opportunity to set the financial independence of Cooper's Ferry Partnership.”

Jeff: This is a document that made us sit up and say: somebody is trying to exert influence or something is not quite right about this.

Neither Phil nor George Norcross had any formal connection to the non-profit. Even so, the brothers were suggesting that Cooper’s Ferry turn over the deal. And they had former business associates lined up to buy the building.

Jeff: And what happened then in the subsequent months, according to these documents, is Cooper's Ferry did everything they possibly could to fight off George Norcross's, uh, aligned companies from taking it over.

Nancy: It all comes to a head in April 2014. A memo in John Sheridan’s handwriting details a call with the two top guys at the non-profit. They’d had a meeting with Phil Norcross and were asking for Sheridan’s help. He’s not just the chairman of their board, he’s a seasoned hand, a political wiz, and he works closely with George Norcross. So they talk on the phone, even though John Sheridan was on vacation with his wife in Barbados.

Jeff: If you're looking for the fingerprints of the party boss of George Norcross, this memo pretty much has it on here. The Cooper's Ferry people, these executives are telling John Sheridan, Phil says we're persona non grata. Then he says, they have to get out of the real estate business. So basically you have, according to this document, you have Phil Norcross, George Norcross telling the chief nonprofit developer in town: you can't be in the real estate business.

Nancy: I recently sent letters to George and Phil Norcross and asked them whether they said the Cooper's Ferry executives would be “persona non grata” and, if they did, what did they mean? They didn’t address that question.

Jeff: These guys have no official position. But this is evidence, of some nature, that they want to control what happens in this town and that they are controlling what happened in this town.

Nancy: So, that leads to really only a week or two later

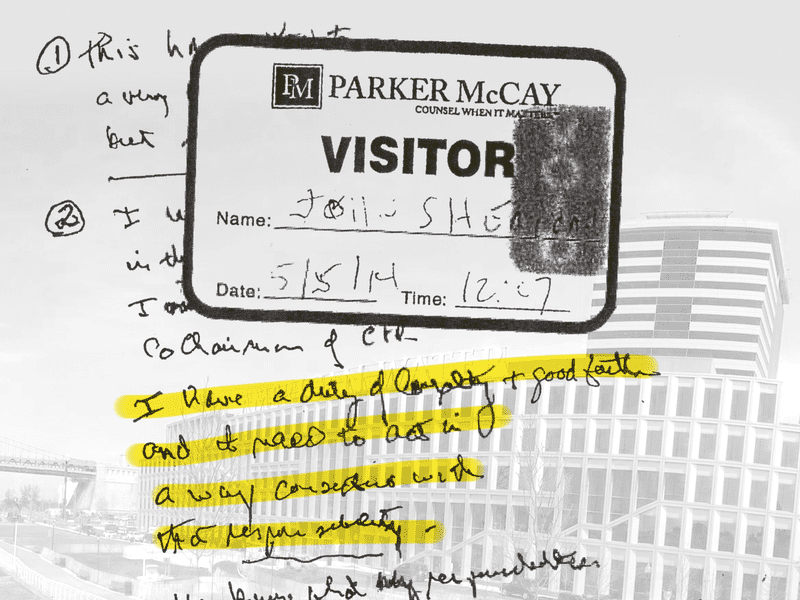

Nancy: John Sheridan has a meeting at Parker McCay, the law office of Phil Norcross.

Jeff: This is about what time is this? Now?

Nancy: This is now May 5th, 2014, at 12:07 PM. I happen to know. Because it has, because he put his visitor sticker from Parker McCay on top of the envelope where he had scribbled notes.

Nancy: I can’t be certain that the meeting was with Phil Norcross. Only that it happened at his law office. The notes on the envelope are in John Sheridan's own handwriting. "I have a duty of loyalty and good faith and I need to act in a way consistent with that responsibility." Responsibility is underlined.

There it is. Scribbled on the back of an envelope. He is standing up for the non-profit. His son Mark has told him it’s his legal obligation to do so.

Nancy: And what was it like when you saw that?

Mark: Uh, it wasn't really surprising that, uh, that he would have been taking notes and, writing it down. I remember distinctly having a call with him, about that. Uh, the one thing was, it was a little bit of a proud moment because he actually took my advice. So, you know, I was happy to see it.

Nancy: Duty. Loyalty. Good faith. Responsibility.

Mark: My father was very, my father for his entire career was always concerned with doing the right thing.

Nancy: John put his visitor sticker on top of the notes. And that recorded the meeting time and place.

It’s May 5th, 2014.

We don't know what happened at that meeting. Or who all was there. But just two days later, the memos and emails show the leaders of Cooper's Ferry Partnership, attend a meeting with the developers who have been pushed on them by the Norcross brothers. At that meeting, Cooper's Ferry offers to sell their right to purchase the L3 buildings. And the emails show, the buyers were asked how much they were willing to pay. This is the part of the deal that is most curious to Mark Sheridan.

Mark: Uh from what I know, I think that Cooper's Ferry gave up a very lucrative developmental right for zero return or almost zero return, uh, without any real justification for doing it.

Nancy: And do you have any, uh, you have any understanding of why they would have done that?

Mark: I, I understand that, uh, they probably would have been cut off from access to redevelopment in city of Camden if they hadn't done it.

Nancy: In the papers there is also an undated handwritten draft of a letter. John Sheridan made an appeal addressed to George. He starts with “Your position regarding Cooper’s Ferry last week was as adamant as I have seen you about any topic in recent memory.” That’s crossed out, and instead he writes: “I have done a lousy job of keeping you apprised of what the organization is all about.”

Sheridan is trying to make the case that Norcross should support Cooper's Ferry. Remember, according to John Sheridan’s handwritten notes, the leadership of Camden’s nonprofit development group were told they were “persona non grata” and should get out of the real estate business.

Coming up after the break, we find out what that means in Camden.

MIDROLL

So what does it mean to be “persona non grata” in Camden? We heard in our last episode from two city councilwomen that voting the wrong way meant losing jobs, committee assignments and getting the silent treatment from city hall when you try to get something done. But what if you’re, say, a business person who doesn’t work for the government?

I didn’t have to go very far to find an example. Because after the L3 deal was sealed, the Norcross brothers turned their attention to other properties on the waterfront.

Jeff: It's one thing to, to be able to engineer a law, that you benefit by to control eventually buildings and tax breaks coming to the waterfront. But he didn’t own the waterfront yet.

Jeff Pillets and I spent a couple of months tracing property records to figure out how George Norcross and his business partners came to own that land.

Jeff: So step one is to get the tax breaks done. Step two is to buy the property and there were these businessmen who had been here many years before George.

Nancy: Jeff is talking about people like Carl Dranoff, a real estate developer from Philadelphia. He is one of the hottest builders in Philly––and his specialty? Turning old industrial buildings into high end apartments. And he was actually recruited by Camden officials in the late 1990s to invest in the city. Dranoff was considered a hero when he invested in Camden by converting the old RCA headquarters into luxury lofts.

But now he and the city are involved in a lawsuit. Dranoff says he was blocked by City Hall – first – from moving forward with his projects, and then, trying to sell and get out.

I reached out to him for an interview; Dranoff declined. But there are depositions from the lawsuit that were buried in the court files.

Nancy: Oh, and let me get those out.

Nancy: I showed them to Jeff.

Nancy: And he says, the reason why is because he had had a falling out with George Norcross and.

Jeff: That's in the deposition

Nancy: It's in the deposition, hang on. I just gotta find it. So this is Carl Dranoff. I remember calling the mayor, the Camden Redevelopment Agency. They would not meet with us. I couldn't get a return phone call. Then, at the end of 2016, I had a major falling out with George and Phil Norcross.

Nancy: Dranoff claims in his sworn deposition that the fight began when George wanted to become a business partner with him for the residential development on the waterfront.

I continued to read the statement to Jeff.

Nancy: I felt like we were being kind of, it was kind of a shakedown - that we were in a situation where we were being asked to participate in a partnership that we really didn't want to participate in. Um, let me skip ahead. And that led to a lot of negotiations and ultimately I think name calling and some pretty aggressive and obnoxious behavior against us. I remember a phone call, where George literally screamed at me and it was a very adversarial situation and we just wanted to get out and we agreed to sell our development rights for what we considered to be a very low number.

Nancy: At that point, Dranoff wanted to pull all his investments in Camden. He tried to sell his luxury lofts. But he couldn’t get the paperwork he needed from city hall and a deal to sell his building for 72 million dollars fell through.

The city has counter-sued, claiming Dranoff didn’t file the proper paper work and owes back taxes. In another deposition, Camden's city attorney detailed weekly meetings she and the mayor held with Phil Norcross. She says she and the mayor were told by Phil to slow down the Dranoff sale.

Jeff: You know, I think that's the Dranoff saga that you see in these court papers. Um, it's stunning in itself, uh, for a raw display of political muscle. If what Dranoff is saying is true, it shows that the arm of the party bosses reached right into the the controls of government.

Nancy: Over the course of five years, parcel by parcel, a large chunk of the waterfront changed hands-a stretch 10 blocks long and 3 blocks wide.

Jeff: Owned by Norcross or developers associated with Norcross or companies that are aligned with Norcross in some way, or his brother in some way.

Nancy: On this beautiful summer day as Jeff and I sat by the waterfront, the change was unmistakable. A half dozen buildings, including an 18-story office tower, a new apartment building and Camden's first hotel in half a century, now sit on land that was once vacant. Most of it is owned by George Norcross, or his business partners or clients of Phil Norcross.

George argues that this was precisely the kind of action needed -- free buildings or free rent for businesses that were willing to invest in Camden. That’s what he told me when I talked to him in 2019.

George Norcross: There has not been a single person that I have seen or read anywhere that with fact has suggested that what's going on in the resurgence in Camden, that's been going on over the last seven years, is anything but extraordinary and spectacular.

Jeffrey Brenner: It's amazing that all of the development that's happened on the waterfront. Like, I was there when it was a field and it was a field for years and years and years.

Nancy: That’s Jeffrey Brenner, the doctor who lived in Camden and ran a clinic for Cooper Hospital when the city was at its lowest.

Brenner: You can pull George apart about how he benefited from it and that's fine. You know, it's an interesting story once or twice, but the bigger question is: is it appropriate to use tax breaks to develop and even out economic activity across a region? And the answer has got to be, yes. I can't even imagine how else you’d move this place forward if you didn't do that.

Nancy: But when Jeff Pillets and I visited the waterfront, there was something missing in all the fancy development there. The people who actually live in the city.

Nancy: Oh, here comes to the street car.

Nancy: Every 10 minutes, an empty street car passes by, on the line meant to bring people down to the river.

Nancy: I didn't see a single person.

Nancy: I wanted to understand why there was no sign of Camden residents enjoying the waterfront. So I visited Keith Benson. He’s lived his whole life here. He’s a Grammy-winning drummer, a 2020 leadership fellow at Harvard, and a community activist. I returned to the waterfront so I could get his take on this shiny new neighborhood.

Keith Benson: The Federal government and this, and the state government really do send more than enough money down here to turn this place around, but it doesn't get to the people it's intended for.

Nancy: Well, that's, we're looking at a place that saw over a billion dollars in state investment right here. This is the view of it. So tell me about this view. What do you see?

Benson: Well, I see a billion dollars that ostensibly came down here to improve the lives of the people in Camden. The lives of the people in Camden are just as bad if not worse.

Nancy: The population of Camden is still declining, according to the 2020 census. The median household income in America is more than 67 -thousand dollars a year. In Camden – it’s 28-thousand. That means half of all the households in Camden make less than that.

Benson: And we have boondoggles of buildings that are not really meant for the people, the residents that the money was earmarked for. So what do you see down here at the waterfront is a glaring, what an undemocratic place looks like.

Nancy: I've heard the same thing from dozens of community activists in Camden over the last few years. Many feel the development on the Camden waterfront has done little for the people of this mostly poor, Black and Latino city. But there are office workers now in downtown Camden where for years there weren’t. I spoke about this with Kelly Francis, the community activist and union leader who knew George Norcross's father.

Nancy: Places all over the country are saying those are the kinds of jobs that we need, right? And that maybe, if those, those folks live in Camden, they would spend money in Camden and then everybody could do a little bit better?

Kelly Francis: Well that's the problem. They're not moving into Camden and they do not shop. They do not stay in Camden. They, they come in at nine and they leave at five. You know, Camden downtown at five o'clock, is a ghost town. There's nothing, it's completely shut down. Everybody leaves and goes back to their suburban communities.

Nancy: And that’s where things stand today.

John Sheridan spent nearly 10 years trying to improve Camden. Christine Todd Whitman, former Governor and friend of John Sheridan, says he took the job at Cooper Hospital to make a difference.

Christine Todd Whitman: He loved South Jersey. He loved Camden. He was committed to it. So, in a way, I think that was, that was really what motivated him. You know, he was about improving communities. And so anything he could do for, for that area, you know, he wanted to do it.

Nancy: Cooper’s Ferry, the non-profit, had hoped to make L3, in part, a real link to the riverfront for the community.

In the letter I sent George and Phil Norcross, I asked why they intervened in the L3 real estate deal – the one John Sheridan had been working on in the months before his death. Their lawyer, Bill Tambussi, says Cooper Hospital, where John Sheridan was the CEO, was also involved in the deal to purchase L3.

Bill Tambussi: And John was told, by me, that he needed to recuse himself from this matter, because he was in a conflict of interest. He certified to that in July of 2014 – months, months before the events of the tragic events of September

Mark: The suggestion that when he was acting solely with respect to Cooper's Ferry, that he had a, a conflict of interest is just untrue. It's a false accusation.

Nancy: That was actually something that John Sheridan had asked his son Mark to research back in the spring of 2014. The question was whether the L3 deal put John’s job as CEO of the hospital in conflict with his role at Cooper’s Ferry.

Mark: The advice I gave my father about that alleged conflict - at the time it was made, it was, it was just manufactured to get my father out of the way.

Nancy: Mark Sheridan’s law firm advised his father that, with respect to the L3 buildings, he was obligated to do what was best for the non-profit – Cooper's Ferry Partnership. At the time, there was no discussion about the hospital buying L3. There was some discussion of the hospital renting office space in part of the building -

Mark: But the fact that Cooper Hospital might sometime in the future, want to lease space – doesn't create a conflict of interest. That conflict arose well after Cooper's Ferry was forced to give up control of that transaction. And the people that are pushing the narrative that he had a conflict – are playing around with the dates to hide what actually happened.

Nancy: And what happened? In December 2014, the hospital – where George Norcross is chairman of the board – got a $40 million tax break. And it also became partners with the new owners of L3. The hospital now owns 49 percent of the building complex.

So what do these documents left on the dining room table mean? I’m not sure, and neither is Mark.

Mark: We're not accusing anyone. What we want, is we want the investigation that wasn't done the first time.

Nancy: What do you make of the documents that your father left on the dining room table?

Mark: My father was involved in a very high dollar real estate transaction that was going to make lots of money for lots of people. And uh, we were asked during the investigation, if there was anything that was going on in my father's life, that might've had anything to do with his death. And, this was what was going on in his life at the time. And I just think that in that circumstance, it's something that should be investigated and looked into. And there were lots of people involved in it and lots of money changing hands. And it was a, a precursor to a whole lot of other transactions.

Nancy: Transactions like more than a billion dollars in state tax breaks for companies that moved to Camden. After Mark Sheridan read the documents left on the dining room table, he brought them to the Somerset county prosecutor and the state attorney general. But he never heard back from them.

On the next episode of Dead End, we talk to a whistleblower about who benefits when the Attorney General turns a blind eye. And what it would take to fix corruption in the garden State.

That's coming up in episode seven. This is Dead End: A New Jersey Political Murder Mystery. I’m Nancy Solomon.

Dead End was reported and produced by me with Emily Botein, Karen Frillmann, and Adam Przybyl. Music and sound design by Jared Paul. Additional engineering by Andrew Dunn and Jason Isaac.

This is WNYC Studios; learn more at deadendpodcast.org. If you like what you hear, give us a review. It really helps introduce the podcast to new listeners. Thank you.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record