EPISODE 5: New Jersey’s Other Boss

( Mel Evans/AP/ / Shutterstock )

Nancy Solomon: This episode includes some salty language that might not be appropriate for all ages.

[music]

John Sheridan was a governmental MacGyver. He loved fixing problems like the state's crumbling highway system. In the oral history in the Rutgers archives, he relishes the details of the transportation system.

John Sheridan: Four leaf clovers were originated in New Jersey. Jersey barriers that everybody-everybody knows are here. Jughandles, uh, I could go on and on and on, but-

Nancy: Sheridan was a problem solver and a creative one.

John: [laughs] I was told, I don't know if this is true, but I was told the governor said, "Are we gonna do that crazy thing Sheridan wants to do?" [laughter]

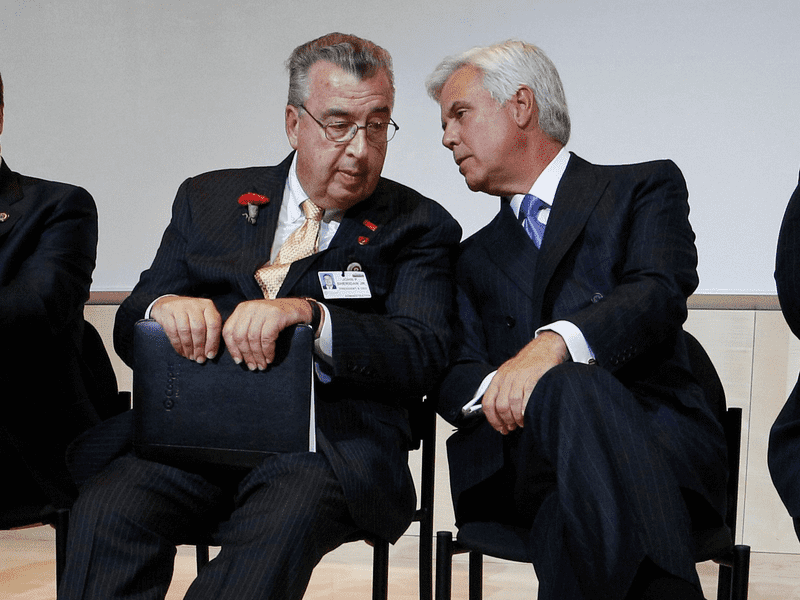

Nancy: Some of his friends and family thought he was crazy to go work in Camden. If I'm gonna understand what John Sheridan was up to in the months before his death, I need to find out what he was doing in Camden, and to understand Camden, I have to take a deep dive into Sheridan's boss. He's New Jersey's other boss, George Norcross. He's the head of a powerful political machine and Camden is his hometown, his passion project, and the spiritual center of his empire.

John Sheridan’s decision to go work at Cooper University Hospital came at a curious time. It was just months after news about those secret recordings – the Palmyra tapes – came out.

The tapes are a rare instance where evidence emerged of the rough and tumble side to the South Jersey political machine. They caught George Norcross bullying and offering a favor to a small town official. He also boasted about his power.

George Norcross: You have to understand something, I'm not gonna tell you this to insult you.

Nancy: You have to understand something, I'm not gonna tell you this to insult you.

George: But in the end, the McGreeveys, the Corzines. They're all going to be with me.

Nancy: But in the end, the McGreeveys, the Corzines. They're all going to be with me

George: Not because they like me, but because they have no choice.

Nancy: Not because they like me, but because they have no choice. For the New Jersey uninitiated, those are two of our former governors.

Palmyra is a small town in South Jersey. A city Councilman wore a wire for state investigators and recorded Norcross telling him he must fire the town's attorney, Ted Rosenberg and in return, the city Councilman would get some benefit at the engineering firm where he worked. Rosenberg was running against the Norcross-chosen-person to run the local Democratic party committee. This is what Norcross says, "I want you to fire that fuck. You need to get this fuck Rosenberg from me and teach this jerk off a lesson.He has to be punished."

Norcross said this. It was a pretty big story in New Jersey and yet just months after the tapes went public, John Sheridan agreed to go work for him at Cooper University Hospital.

I was curious to know what his son Mark thought about it but before we hear that, I need to correct something. In the first three episodes of this podcast, I said Mark was the lawyer for Governor Chris Christie, but at the time of his parents' deaths, he was actually the lawyer for the Chris Christie campaign. Suffice it to say Mark’s connected, and he would know what it meant to go work for George Norcross.

Nancy: And he didn't express any concerns about George Norcross's reputation? This is now post the Palmyra tapes and you know, people know what kind of an operator he is at this point.

Mark: He-- so I-I asked him about that. Um, he had this view that, uh, George's bark was worse than his bite. Um, and that, uh, George really was working to redo his image and wanted to fix Camden. The Norcross family had a long storied history in Camden and my dad believed George genuinely wanted to fix it and I-I think that's been borne out.

Nancy: I'm Nancy Solomon, and this is Dead End, Episode 5. George E. Norcross III was born in Camden and grew up in Pennsauken, a blue-collar town right next door. He's 66. A few years ago, he was said to be worth 245 million collars. He owns a multimillion-dollar insurance brokerage that does a very lucrative business with government entities all over New Jersey. Until 2021, he was a member of Donald Trump's Mar-a-Lago. Unlike Trump, Norcross didn't inherit wealth from his father, but he got something else, something even more valuable, a lesson in how to amass political power.

George: Undoubtedly, my father influenced, uh, me greatly as he did each of my, uh, brothers.

Nancy: This is a recording of a Chamber of Commerce interview with Norcross from 2018.

George: And from a very, very young age, my dad used to bring at least two of us to every meeting he had on the weekends and we'd wear our suits and bowties.

Nancy: His father, also named George Norcross, was a television antenna installer at the RCA factory in Camden. And that got him involved with union organizing.

Kelly Francis: His father was a- was a union, a bonafide union, uh, leader. You know, he was the real deal.

Nancy: Kelly Francis came to Camden in 1949 as a kid. He worked for more than 30 years at the Post Office and he knew the elder Norcross. They were both involved in unions in Camden.

Nancy: Was his father a good guy?

Kelly: Oh, oh, his father was great. His father and I were good friends.

Nancy: George's father led a Camden Labor Coalition that represented 90,000 workers. That put him at the table with powerful people and he made sure his four sons would learn from that access.

George: We'd be told to sit and not speak and listen. My father was a big believer in listening and learning.

Nancy: This was a pivotal moment in Camden's history. Until the 1960s, the city had thrived.

Advertisement: Now a brief intermission in which the Campbell kids discover that mother knows best.

Nancy: Camden was home to Campbell Soup, and one of the first record companies in the country was there too. It eventually became RCA and released some of the biggest records in American history: Enrico Caruso, Duke Ellington, and Elvis.

[music]

Well, since my baby left me,

Well, I found a new place to dwell,

Well, it's down at the end of Lonely Street,

At Heartbreak Hotel.

Nancy: There were lots of jobs that drew families to move to Camden like Kelly Francis, the one who knew the elder Norcross. Before he joined the post office, he worked at Campbell Soup.

Kelly: Loading freight cars, shipping soup all over the country, back in the 1950s. And of course, it paid for my college education. I was able to work my way through my college education.

Nancy: In the 1950s, the city had 124,000 residents and 86% of them were white. But this is when white residents began to leave. It's the same story that happened all over the country. New highways enticed middle-class families to move to the suburbs. Some white suburbanites fought to keep Black families out and banks blocked them from getting mortgages. The racial composition of Camden began to change. One of those families that left for the suburbs was the Norcross family. And then years later, after the education at the knee of his union leader father, young George headed off to the Camden campus of Rutgers University.

George: I'd have breakfast with a lot of my colleagues going to class, and then they'd go to class and I'd read The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times.

Nancy: He dropped out, started his own business, volunteered on the campaign for the Democratic mayor of Camden, and started raising money for local candidates.

Nancy: Tell me-

Kevin Riordan: Yeah.

Nancy: -w-what's your first memory of George?

Kevin: Oh, I have one. [laughs] It's-

Nancy: Kevin Riordan came to Camden in 1976 to work for the local newspaper.

Kevin: I was in the Parking Authority and I looked at the wall and there was this giant portrait of him, Norcross, photo portrait. I mean, you know, it wasn't, you know, the size of a mural, but it was very large and he must have been chairman of the board of the Parking Authority at that time.

Nancy: It's the only official government position that Norcross has ever held. At the age of 22, he was appointed by the mayor to run the Camden Parking Authority. Riordan has reported on South Jersey off and on for the past 45 years, now at the Philadelphia Inquirer. He covered that mayor who ran Camden like his fiefdom and the Parking Authority was the perfect place for Norcross to learn about the power that comes with doling out patronage jobs and government contracts, you know, who gets hired and who makes the money for things like picking up garbage or printing office forms. Then the mayor went to prison for bribery, and that meant there was no party boss running Camden.

Kevin: George stepped in behind the scenes and filled the void.

Nancy: So young George, chairman of the Parking Authority and never elected to anything, becomes the new political boss of Camden.

Kelly: Like I say, I gotta give credit.

Nancy: Kelly Francis, the guy who knew Norcross' dad, says George took a different route to power.

Kelly: I mean, the guy came up with a very unique, uh, style of political boss-ism. Because prior to him, all political bosses held political office.

Nancy: Norcross didn't run for office, but he handpicked candidates, raised money for them, and hired expert campaign consultants and pollsters. By 1980, the population of Camden had dipped to 85,000 and jobs were disappearing. Much of the industry had left, leaving behind vacant land and abandoned buildings.

Newscast: The skyline of Philadelphia is almost painful to look at from here because it's so close. Such a glittering symbol of wealth and prosperity compared to here. It's the highest crime rate in the country, the highest murder rate in the country, in the poorest city in the country.

Nancy: By the 1990s, Norcross had a network across South Jersey who owed him. Mayors and people who served on city councils, school boards and even the state legislature.

Micah Rasmussen: There's nothing harder to do in politics than to ask somebody for money.

Nancy: Micah Rasmussen is the director at a center for politics at Rider University. But he's not just an academic. He ran local campaigns in South Jersey. He worked in the state legislature and he worked for a governor. Throughout it all, he saw how Norcross became powerful by raising campaign cash for local candidates.

Micah: There's nothing more unpleasant. Unless you're good at it. Unless-unless you're just you know masterful at it, as Norcross is.

Nancy: Rasmussen told me Norcross was careful about the way he called in favors.

Micah: One of the things that Norcross was good at was not asking too much, um, at least at the outset. He-he wasn't on the phone with you all the time.

Nancy: The politicians who took Norcross' money, they could be independent, as long as they voted with the boss on the things he cared about.

Micah: You knew the votes that were important, who was going to be the speaker of the assembly, who was going to be the Senate president, who was going to wield the power. Those were votes where you-- That-that-that came with the bargain.

Nancy: The strategy worked. In 2009, the Norcross allies elected Steve Sweeney president of the state senate. That’s the most powerful person in the state legislature, and makes him second only to the governor statewide. That meant Sweeney could control what bills came up for a vote and who would serve on which committees.

The relationship between Sweeney and Norcross is often boiled down in news articles, to one phrase: Sweeney -- the childhood friend of Norcross. But I got my hands on an email chain from 2014 that showed the kind of power that Norcross held over Sweeney. In the thread, Sweeney received a list of bills from his assistant that are ready to be put up for a vote. He forwarded the list to Norcross, with a note: is there anything on this list that bothers you? In a one word reply, Norcross approved Sweeney putting the bills up for a vote. He wrote simply, “Good.”

Shaneka Boucher: George Norcross is the CEO of the Democratic Party and it operates like any other business, any other corporation.

Nancy: Shaneka Boucher is a city councilwoman in Camden. She got elected with the help of the Norcross machine. But on one issue she refused to vote as told. She says that's a rarity on the seventh person council.

Shaneka: And, um, it was a six-one council vote, right? Like I was the only person on council that voted no. And so the retaliation starts small. So it's really like, "Well, we're not gonna talk to you as much. We'll isolate you a little bit." And I'm comfortable with that. I'm not from, uh, South Jersey. So I'm from New York, so I'm a little--

Nancy: Boucher was new on the city council and she gradually began to speak her mind more and more.

Shaneka: What they was trying to explain to me is like, "It's not that we don't have issues." It's like when you have a family you don't talk about those issues outside. But because I was talking about them outside, they didn’t like it. It's almost like it's embarrassing and they say that a lot. They said I embarrassed the fa-- I guess, you know your parents say you embarrass the family. They told me a lot of times like, "You are embarrassing the family."

Nancy: What form does the retaliation take? Like what would be some of the-the small punishments?

Shaneka: So, for instance, like me working on a committee and now your committee’s changed or people that would have called or returned your call on things that you were working on together, now they don’t call you back.

Nancy: One elected official told me that serving on the Camden City Council requires being – a “yes yes person”, doing what the machine wants. But for the first time in decades, there are three City Council members who are speaking out. And they’re all women. I recently sat down with them to hear how the machine works.

Marilyn Torres: I hear a lot of George Norcross, but to me, it's our fault accepting positions, accepting jobs

Nancy: In 2010, Marilyn Torres became the first Latina to be elected to the Camden city council. She voted in line with everyone else and she was rewarded with an appointment to lead the Camden Redevelopment Agency.

Marilyn Torres: What do we become to be? A yes, yes person. And that's what I was: a yes, yes person.

Nancy: In a controversial decision, Torres and the rest of the city council voted to turn the Police Department and the millions of dollars that came to Camden for law enforcement over to the county and that broke the union.

Marilyn: And I hear the community complain: "Don't vote yes on this because this is not good for our city," and many times I went home and I cried. I regret that for the rest of my life.

Nancy: Well, Marilyn, when you-you were hearing from your constituents that they didn't want you to vote for it, and you felt like you had to vote for it and you went home--

Marilyn: No, I didn't feel like I had to vote for it. I was forced to vote for it because I was a yes-yes person.

Nancy: Yeah but who-who-who had their thumb on you, forcing you to vote for it?

Marilyn: It's like-like the octopus is pulling his strings.

Nancy: The octopus is pulling his strings. It's a bit of a mixed metaphor, but I understood exactly what Marilyn Torres meant because there's a book about the Norcross machine in Camden and on its cover there's a drawing of a huge octopus hovering over city hall.

Tom Knoche: You don't do business on any kind of scale in Camden unless you pay your dues to the Norcross organization.

Nancy: Tom Knoche is the author of that book and a lecturer at Rutgers University in Camden. Every town, school district, and Parking Authority awards contracts to purchase equipment or pave roads, or pick up the garbage.

Tom: When I did the book, you know, I researched who were the contractors that worked with all these big quasi-public entities and, uh, compared that to the donor list for the different Norcross entities and they-they're a match.

Nancy: It's political machines 101. Norcross would raise money for candidates and when they were elected, they would do favors for him and his stable of campaign donors.

Tom: So with the amount of money that he's able to amass in that way, he has this-this very sustainable setup.

Nancy: But I wanted to understand why George Norcross was more powerful than any other political boss in the state, and I knew the exact person to explain it.

Matt Katz: Well, you know, I mean, New Jersey, New Jersey is absurd. New Jersey is absurd, is not the entirety of my statement, but it might as well as well, it could be.

Nancy: That's coming up after a short break.

MIDROLL

Matt Katz: My name is Matt Katz. I'm a reporter at WNYC and for many years I covered Chris Christie.

Nancy: Matt is my colleague and friend, and he taught me a lot about how political machines work and before he covered Christie, Matt was a reporter in Camden where the power of George was ever present.

Matt: People told me in south Jersey that members of the planning board, um, in a local little local town would have to be approved by Norcross. Um, people would know that they had to give to the machine because they would get invitations to events, to fundraisers.

Nancy: I found a perfect example of this in an old lawsuit filed in 1997. It's hard to find evidence that shows how the machine operates, but this lawsuit by a Camden landlord named Rahn Farris, it offers up a detailed account. He received 10 tickets in the mail to a political fundraiser. It was the kind of thing Matt Katz heard about all the time.

Matt: Whoever got the invitation was under no obligation to go. They just were under an obligation to buy the number of tickets that was already in the invitation for them and it didn't matter if they showed up to the thing or not. They just had to funnel money into the machine.

Nancy: Farris owned an office building in Camden, and he rented space to a Camden county agency. Farris ignored the invitation to spend $10,000 on a party fundraiser and the next thing he knew, he got an invitation of a different sort – to meet with George Norcross. Farris would later testify, "I walked in his office and he said to me something to the point of how do I get you to be a team player?" I said, "if you're talking about the tickets, I'd love to be a team player, but I can't afford the tickets at this point in time." Farris testified that when he returned to his office after his meeting with Norcross, his tenant, the county agency, already knew what had happened.

He was warned, "You're gonna have problems with Norcross." The next thing he knew the county stopped paying its rent. Farris ultimately dropped the complaint against Norcross and settled with the county.

It could be a fundraiser for the Democratic party or a political action committee or a specific candidate. Norcross became the premier political fundraiser in New Jersey and that helped him grow his network of elected officials. But the inquiry into the Palmyra tapes was still working its way through the system.

Remember Norcross boasted that he controlled governor Jim McGreevey. Turns out that under McGreevy's attorney general the investigation stalled. The top attorneys in that department were transferred out. In an unusual move, the attorney general at the time tried to hand off the case to the federal prosecutor.

Chris Christie: There is no one beyond the reach of the law.

Nancy: And that federal prosecutor was an up and comer who was going after corrupt politicians in New Jersey: Chris Christie.

Christie: There is no one above the law, there is no one immune to the law.

Nancy: But when it came to the Palmyra case, Christie treated the potential corruption investigation like a hot potato. He refused to take the case.

Matt: But, you know it became whispers for

Nancy: Matt Katz

Matt: For years, whispers that only grew louder as Christie and Norcross became publicly closer through the governorship.

Nancy: Christie understood that to be a successful Republican governor in a Democratically controlled state would require an alliance with the most powerful boss of those Democrats.

Matt: Because that's exactly what happened, um, you know Christie got elected in 2009, started wooing Norcross immediately. They started going to Eagles games together and Norcross has a box at the stadiums and they started working first behind the scenes and then very publicly on all sorts of legislation and the byword through it all was-was bipartisanship.

Christie: I can't believe it, but I am honored that George Norcross is here today.

Nancy: Christie even gave him a shout out at his final state of the state speech before leaving office in 2018.

Christie: And I'm even more honored to call him my partner in this rebirth of Camden. We did it, George, and thank you for being my partner.

[applause]

Nancy: The two men worked together to turn the Camden police department over to the county, and convert a large number of public schools to charters. Then they remade the tax break program, giving Camden huge benefits. During those eight years, Norcross reached his zenith of power.

Nancy: So nice to virtually meet you, Mr. Norcross.

George Norcross: Nice to meet you, good morning.

Nancy: I produced a series of stories about Norcross in 2019 and early in that year he agreed to speak with me.

George: Camden, dubbed Americas most dangerous city at one time, was a place that in the, uh, center city area and probably almost every neighborhood, uh, in-in the city, you could buy drugs, buy sex, or get killed all in the same block.

Nancy: So Norcross ushered in a redevelopment plan for Camden and he hired a wise hand, a guy who knew how to make government work better, John Sheridan.

John Sheridan: Camden city, uh, is one of the poorest cities in the United States with approximately 40% of its households living below the federal poverty level. And Cooper is the city's main healthcare provider.

Nancy: That's from a 2009 hearing on Capitol Hill, when Sheridan testified about health insurance. He was CEO of Cooper Hospital, the city's largest employer and his goal was to use the hospital to drive economic development in Camden.

Jeffrey Brenner: He was a risk-taker too. He was not afraid to take bold risks.

Nancy: Jeffrey Brenner worked for Cooper Hospital, first as a doctor in a small three-room clinic in the Cramer Hill neighborhood of Camden, and he would later run a much larger health institute for the hospital. He told me John Sheridan was a mentor.

Jeffrey: And a colleague, and a friend. He asked lots of questions. He was an ambitious leader, a thoughtful leader, and he was at a point in his career where like, he had nothing to prove he-he could have retired, you know, he was really dug in on a very idealistic cause of improving Camden.

Nancy: Did you- Did-Did you ever get a sense of like, what his vision was for, like, what he wanted to see for Camden and his role in it?

Jeffrey: Was reconnecting Camden to the region and to the state and he was-- definitely thought Cooper has an important anchor.

Nancy: It was a vision that his son Mark found hard to believe at the time:

Mark Sheridan: My initial reaction was, it was a crazy idea because you're never going to fix Camden. Um, and I'm not sure you can fix an ailing hospital system in Camden. Uh, look I was wrong on both fronts. So, uh, you know, to his credit, he saw a way to do it. And to George's credit, they saw a way to do it together

[music]

Nancy: John Sheridan and George Norcross shared the same vision, create a top-notch hospital, recruit a medical school to be located there, and then attract private investment to downtown Camden. And that shared vision was working. The two men were on the same page and the hospital had become a crucial driver in the city's redevelopment. On the next episode, we'll find out what was happening on the Camden waterfront, and why that was getting in the way.

Jeff Pillets: It's easy to say that he controls things but it's hard to see the fingerprints, but they-they do exist, we've seen them, and when you do see them it's a stunning thing.

Nancy: That's coming up in Episode 6. This is Dead End: A New Jersey Political Murder Mystery. I'm Nancy Solomon.

[music]

Dead End was reported and produced by me with Emily Botein, Karen Frillmann, and Adam Przybyl. Music and sound designed by Jared Paul. Additional engineering by Jason Isaac, Andrew Dunn, and Sham Sundra.

[music]

We were sad to learn just weeks ago that Kelly Francis died in Camden in March of this year at the age of 87.

[music]

This is WNYC Studios. Learn more at deadendpodcast.org. If you like what you hear, give us a review. It really helps introduce the podcast to new listeners. And thank you.

[music]

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.