EPISODE 4: The Dirt on the Garden State

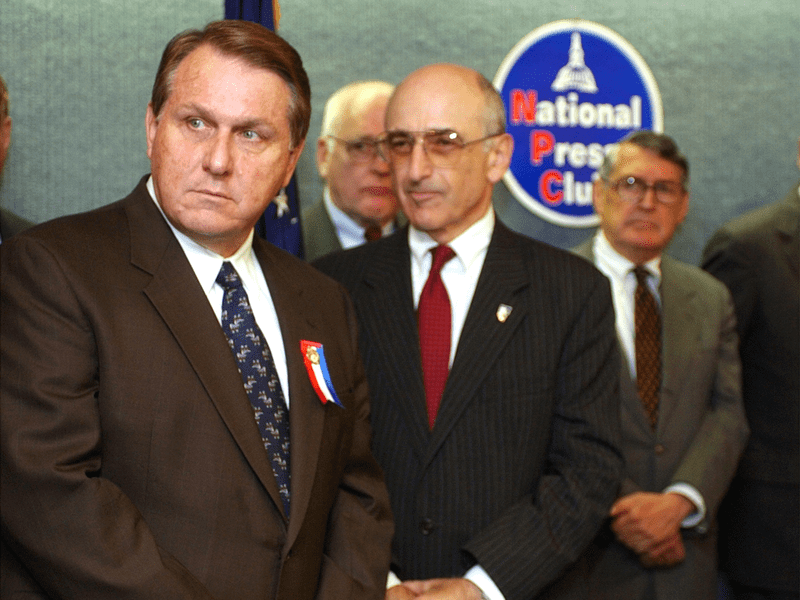

( Photo credit Susan Walsh/AP/ / Shutterstock )

Nancy Solomon: I've got some intriguing leads. There's DNA on the handle of the knife that killed Joyce Sheridan.

Lawrence Kobilinksy: And it indicates the presence of another male individual.

Nancy Solomon: But it's too tiny a fragment to make a match on a DNA database. And I can't go anywhere with the story of the mystery car that could've been casing the neighborhood.

Tom Draper: Someone who would be unfamiliar with our area probably just didn't know that they were moving quickly into what was a dead-end street.

Nancy Solomon: There might have been video surveillance footage of cars arriving and leaving that day because there's only one way in and out of the neighborhood, but the Somerset prosecutor's office won't release any of their investigation files. And there's the fire poker that might have been used to crack John Sheridan's ribs and chip his tooth.

Eddie Rocks: I'm sure it was never fingerprinted and it was just in the pile in the bathroom.

Nancy Solomon: So at this point, without subpoena power, my investigation into who killed the Sheridans is stuck on a cul-de-sac.

[music]

This is Dead End, Episode 4. I'm Nancy Solomon.

[music]

I'm going to be honest with you, I haven't solved this murder, at least not yet, but I'm rattling a few cages, and things might be changing. I'm getting phone calls from powerful people who want to know what I know. I might not have subpoena power, but there's a statewide law enforcement agency that does. The attorney general was urged by the Sheridan family to get involved. Now this has become another question I want to answer: why didn't the state attorney general intervene? I'm not the only person who wanted more answers. A year and a half after the murders, and, yes, I think we can definitely say murders, some 200 prominent citizens sent a letter to the state attorney general.

It's signed by a state Supreme Court justice, two former attorneys general, and three former governors, and some of the biggest names in New Jersey's legal world; and friends of the Sheridans and his boss, George Norcross. They all wanted suicide to be removed from John's death certificate.

Christine Todd Whitman: I'd signed the letter along with the other governors.

Nancy Solomon: Former Governor Christine Todd Whitman still feels about it.

Christine Todd Whitman: calling for a full investigation and calling into question what had been done at the time because it seemed as if a lot of things were missed. It just didn't make any sense anyway. Knowing John and Joyce, it just didn't make any sense from the get-go.

Nancy Solomon: A few days after the letter went public, it seemed to have an impact. Governor Chris Christie announced he wasn’t renewing the appointment off Somerset County prosecutor, Geoff Soriano. But Soriano was given a soft landing that didn't make the news. He was hired on at the attorney general's office. And despite the letter being signed by the biggest names in New Jersey legal circles, the attorney general never got involved with the investigation.

So I want to find out--who killed the Sheridans? And I think it's important to understand why the investigation was not pursued. I'm back to the basics of my day job – covering NJ – looking at the way money and politics come together.

Politics is the world John Sheridan and I shared. He was on the inside. I’m on the outside looking in. And to understand what he was up to at the time of his death, and why it’s so important – we need to enter that world. And it starts with a trip to meet a man whose experience with New Jersey crime and corruption goes back 60 years.

Okay, I'm in Princeton. On my way to interview Ed Stier. I'm pretty excited about it because I've been talking to Ed over the last couple of years, but he has been reluctant to ever do an on-the-record interview, so today is the day.

Ed Stier's large house is set back from a narrow street with an electric gate that sweeps open when I pull up. When I get out of the car, the first thing that greets me is a once in every 17 years insect invasion. My God, cicadas.

Ed Stier: My goodness, you are on time.

Nancy Solomon: Yes, I'm sorry. [laughs]

Ed Stier: Come on in.

Nancy Solomon: Are you going to sit at your desk?

Ed Stier: Wherever you want me to.

Nancy Solomon: There's a little sign in Stier's wood-paneled office of the kind of career he's had. No photos with famous people, no framed headlines, but he's worked with or known a lot of major players in New Jersey and New York, including John Sheridan.

Ed Stier: So when he and his wife died, I was, of course, shocked. And I had come to know his son, Mark, and I sent a note to Mark expressing my condolences and I began to monitor as a private citizen what had happened and how the investigation was being conducted.

[music]

Nancy Solomon: Investigations are Stier's specialty. He got his start as a federal prosecutor, then took a job at the attorney general's office in New Jersey in the 1960s, and it was a critical moment for New Jersey. Organized crime had infiltrated government, unions, and industries like construction and garbage. In September of 1967, Life Magazine, which was a major source of news at the time, published an article that embarrassed state leaders.

Show this to me.

Stier still has the original. It has Red Sox slugger Carl Yastrzemski on the cover, and inside, there's an ad for a new Ford for $1,800.

Ed Stier: Well, this Life magazine article which is quite lengthy.

Nancy Solomon: I love this headline; Mobsters In The Marketplace: Money, Muscle, Murder.

Ed Stier: And it was literally true. There were stories of trunk loads of cash coming out of Las Vegas back to New Jersey. Carlos Marcello racketeers.

Nancy Solomon: King Thug of Louisiana, these are great headlines. [chuckles]

Ed Stier: And even though everybody knew that organized crime was very powerful in New Jersey and had political connections, the shockwaves that were sent through the media, through the political system in New Jersey by the Life Magazine articles was overwhelming.

Nancy Solomon: In response to the article, the attorney general created the Division of Criminal Justice.

Ed Stier: Ad that is a state-level criminal investigation resource that is beyond anything that any state had or has to this day.

Nancy Solomon: Ed Stier would become one of its most accomplished directors. Now, there was a state law enforcement agency that could take on crime beyond the scope of local police. Just like the FBI's role nationally, the Division of Criminal Justice would investigate criminal networks across county borders and take on complicated cases.

Ed Stier: We investigated some of the states leading racketeers and brought cases. Sam DeCavalcante, the head of the only New Jersey-based mob family.

Nancy Solomon: Tony Soprano was modeled after him.

Ed Stier: Gyp DeCarlo if you've seen Jersey Boys. Seems rather benign in the musical, but in truth, he was a leading racketeer in New Jersey and had tentacles into legitimate government and law enforcement.

Nancy Solomon: And they convicted Bayonne Joe Zicarelli, who had the head of the state police on his payroll.

Ed Stier: We put the first bug ever installed by state law enforcement in Zicarelli's office.

Nancy Solomon: It wasn't just New Jersey. This was going on across the country, and the biggest of those cases, the Teamsters. Tell me about the Jimmy Hoffa case.

Ed Stier: The kidnapping and murder of Jimmy Hoffa was one of the most shocking events in the modern history of law enforcement.

Nancy Solomon: Jimmy Hoffa was the head of the Teamsters Union from the 1950s until the '70s. Back then, the Teamsters controlled the trucking industry, a huge part of the national economy. They would slash tires, blow up trucks, or any number of things to win contracts, but for the bad stuff like killing people, Hoffa enlisted actual mobsters. Ed Stier was of a generation of young prosecutors who were going after the mob in New Jersey. At the same time, the Feds were taking up the fight too..

Ed Stier: When Bobby Kennedy became the attorney general, he created a squad that became known as the Get Hoffa Squad.

Nancy Solomon: Robert Kennedy, the president's brother, had been appointed US attorney general and he was determined to rid organized crime from the Teamsters by passing new racketeering laws.

Robert Kennedy: These laws are aimed at those who are in the business of prostitution, who are in the business of gambling, who are in the business of narcotics.

Nancy Solomon: But Jimmy Hoffa was not intimidated.

Jimmy Hoffa: And I say to the millions of members of organized labor, have heed because those who fight for you and fight to win will find that out of this conviction, the zeal of Attorney General Robert Kennedy will be to destroy you unless you give in.

Ed Stier: They pursued Jimmy Hoffa until they found a case, prosecuted him, and convicted him.

Nancy Solomon: After a stint in prison, Hoffa returned to the Teamsters, but according to an interview I found on Youtube with Michael Franzese a former mobstere.

Michael Franzese: When he came out of prison, he was told to lay low and just stay back, and he refused to do that, he didn't want to give up his position. There's no question he was taken out by my former associates. Now, the question is always where is he buried? That's what everybody wants to know. I can tell you this, he's not in the Meadowlands, that's for sure. New Jersey, the stadium, he's not there and they will never find Jimmy's body.

Nancy Solomon: Members of the New Jersey Teamsters local were suspected, but never convicted, and that's when Ed Stier was brought in.

Ed Stier: They were so brazen that they felt capable of carrying out the murder of someone as important as Hoffa was, showed the extent to which corruption and organized crime had grown in this country. The law enforcement response, the legislative response was dramatic.

Nancy Solomon: So, you're basically the guy who rid the Teamsters Union of the mob. Is that fair to say?

Ed Stier: Well, I’m the guy, I guess it's true that I am the guy who rid Local 560 of the mob.

Nancy Solomon: I'm not just taking a walk down memory lane. Ed Stier believes the Jimmy Hoffa case is not so different from the Sheridan's.

Ed Stier: It wasn't just a murder, the question is why? What's behind it? What underlies a decision that somebody or some group of people have made to murder somebody of great prominence. And what that means is that under the surface, there's a massive problem. What you're seeing is the tip of a gigantic iceberg. Maybe the same is true with respect to John Sheridan.

Nancy Solomon: We’ll be right back.

MIDROLL

Nancy Solomon: My visit to Ed Stier happened before the news broke earlier this year about Sean Caddle. He's the Jersey campaign consultant who hired two hitmen to murder a political operative. Remember, hat's another murder of a guy involved with Jersey politics that happened just four months before the Sheridan's and the guy is stabbed and his apartment set on fire.

Bratsenis: George G E O R G E John, J O H N. Brett, send this B R a T S E N I S.

Nancy Solomon: One of the hit men pled guilty just recently.

Bratsenis: Date of birth, 1/10/49.

Nancy Solomon: Looking old and weak, the 73-year-old gave his plea in an online court hearing.

Court Hearing: Did you travel from Connecticut to New Jersey. For the purpose of participating in the murder of Michael Galdieri? Yes sir.

Yes sir.

During that meeting? Did Mr. Cattle pay you thousands of dollars of cash in exchange for all the area? Yes sir.

Nancy Solomon: So law enforcement was investigating two murders, four months apart, with the same M.O. and both victims were involved with New Jersey politics.

I mean it's kind of crazy that it seems nobody made any connection between these two cases. This is what Ed Stier was trying to explain to me: The Division of Criminal Justice was set up to see patterns, make connections

Ed Stier: Even before Mark Sheridan came to the attorney general to ask the state to supersede, the state should have done it on its own. The prosecutor should have been informed that the state was taking over the crime scene from the very outset. John Sheridan wasn't just a local figure in Somerset County, but he was the head of Cooper Hospital down in Camden, so now you've got a couple of different counties involved. The circumstances of their deaths were very, very unusual. And for the Somerset County prosecutor's office to walk into the crime scene and say, "Oh, this is obviously a murder-suicide" before any investigation took place was criminal negligence.

I realize that's a very strong term, but I'm very upset about it because it is completely irresponsible. They couldn't have done a worse job if they intended to mess up that investigation. They destroyed the crime scene, made it impossible for anybody to come in later on and do any decent forensic work. This is precisely what the Division of Criminal Justice was created to deal with.

Nancy Solomon: Do you have any analysis or, uh, a frame for thinking about why the division of criminal justice didn't step in?

Ed Stier: I really don't understand it. I wish, I wish I could explain it.

Nancy Solomon: I’ve called Hoffman and every assistant attorney general who reported to him, uh, and the top tier of the division of criminal justice. And I have not been able to get one person to talk to me. And I understand that they don't want to talk about investigations and such, but how should I interpret the wall of silence that I've been met with about this case?

Ed Stier: What you're asking about is the exercise of, uh, discretion. You're not asking about the details of evidence that was obtained as a result of grand jury subpoenas. You're asking, uh, why didn't you intervene? It seems to me that's a legitimate question to which, um, they should be prepared to respond. I don't know. Obviously nobody has a good explanation for you or you would have heard it.

Nancy Solomon: The Division of Criminal Justice had investigated the biggest cases in New Jersey, whether it involved organized crime or political corruption or both, but Ed Stier told me that began to change about 20 years ago.

Ed Stier: The level of sophistication, the aggressiveness of the Division of Criminal Justice seriously declined.

Nancy Solomon: That would have been during the Jim McGreevey administration. When he was sworn in as governor in 2002, McGreevy appointed a new attorney general, and suddenly, the top people at the Division of Criminal Justice were reassigned. Corruption cases mysteriously disappeared. I called Governor McCreevey. He has a new life now working to help people recover from addiction and stay out of prison and he has no interest in rehashing the past. But Ed Stier argues this is the period declines.

Ed Stier: Precisely what the reasons were remains to be exposed at some point, but clearly, the record shows that the state, state law enforcement was extraordinarily ineffective during that period.

Nancy Solomon: One of the high-profile case to disappear, it's known as the Palmyra Tapes Case. A local city councilman wore a wire and captured Norcross, who would later become John Sheridan’s boss, trying to bully him into firing a city employee. On the tape, Norcross can be heard bragging about controlling Governor Jim McGreevey and the US Senator at the time, Jon Corzine.

George Norcross: You have to understand something, I'm not going to tell you this to insult you, but in the end, the McGreeveys, the Corzines, they're all going to be with me. Not because they like me, but because they have no choice.

Nancy Solomon: The McGreeveys, the Corzines, they're all going to be with me, not because they like me, but because they have no choice.

Nancy Solomon: In the coming episodes, I’m going to tell you a lot about George Norcross. And he’s not happy about this podcast.Turns out Mr. Norcross is listening carefully.

I had an hour long video call with his lawyers just as we were putting this episode to bed.

Norcross was there, He didn’t speak – and he, three lawyers and two spokespeople didn’t turn on their cameras. Attorney Michael Critchley did most of the talking.

Michael Critchley: if you're going to be fair, make sure you emphasize that you have no evidence whatsoever that George Norcross had anything to do with the Sheridans’s murder investigation, that tragedy I don't want to get this to be adversary because if anyone even suggests intimates or infers obliquely directly indirectly that George Norcross was somehow involved in John Sheridan and Joyce Sherman's tragic death, the next letter, you receive from me is a litigation hold notice.

Nancy Solomon: I had to look that up. It’s when you get a letter saying you are about to be sued and you’re legally required to keep documents.

Suffice to say, they’re not happy I’m talking about Norcross. And they wanted me to agree to say on the podcast that I have no evidence that George Norcross was involved in the Sheridan deaths.

Michael Critchley: If you're not going to give me that commitment, I would recommend we terminate this proceeding because other than that, it's just wasted time.

Nancy Solomon: I told them I would consider it, but without a promise, the meeting ended abruptly and I never got to ask my questions of George Norcross. But fair enough. I’ll say it. I don’t have any evidence that George Norcross had anything to do with the deaths of the Sheridans.

But there IS a reason I’m talking about Norcross. On the next episode, we take a trip to Camden – where John Sheridan worked and where George Norcross is king.

Tom Knoche: You don't do business on any kind of scale in Camden unless you pay your dues to the Norcross organization.

Shaneka Boucher: George Norcross is the CEO of the Democratic party and it operates like any other business, any other corporation.

Nancy Solomon: That's coming up in Episode 5. This is Dead End, a New Jersey political murder mystery. I'm Nancy Solomon.

[music]

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.