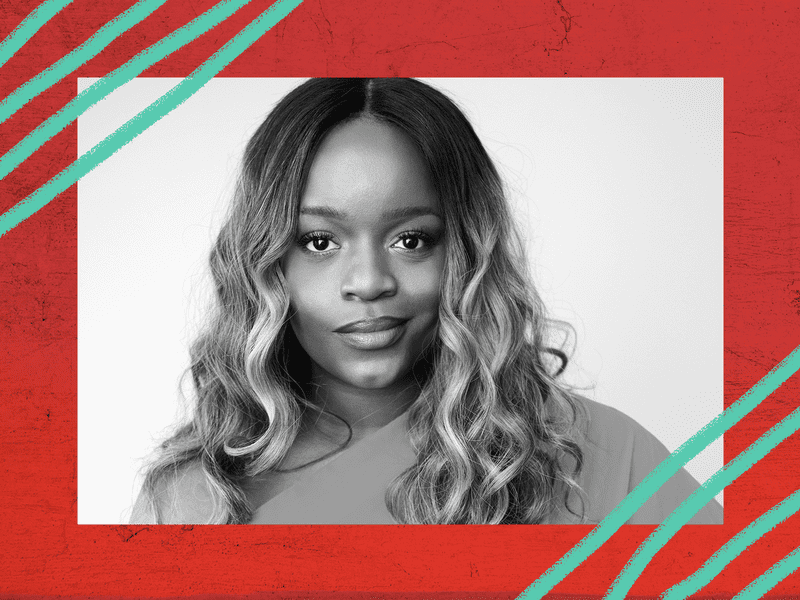

3. Brittany Packnett Cunningham on Activism in Crisis

In 1968, James Brown released the hit song “I’m Black and I’m Proud.” I was born a year later, and the small, insular, New England world I was raised in, was completely white. It would take me decades to understand the meaning of both the James Brown song and the Black is Beautiful movement that inspired it.

When I finally got to college, I discovered black literature and history, and met and became friends with black folks — black folks who embraced me and loved my blackness. And I started to love it too.

My white adoptive family hadn’t known that learning to love one’s blackness requires a black community — and that the creating and caring for blackness alongside other black folks is where that love is born and nurtured.

And that is what I admire so much about the educator and activist Brittany Packnett Cunningham. Brittany is one of the hosts of Pod Save the People, and she’s also a contributor to NBC News and MSNBC. She sees and loves her own blackness, while also seeing and loving mine, and every black sister and brother she comes into contact with.

Brittany is a native of St. Louis, Missouri, the daughter of a pastor and an ordained Baptist minister. And she absolutely practices and embodies the necessary work of upholding community — you might even call her a pillar, except that pillars are made of stone, and Brittany is the total opposite. She is emotionally porous, vibrant, and always, always listening and looking for ways to evolve.

I had been aware Brittany and her work -- I follow her on social platforms -- but we got to meet face to face and really spend time with each other a couple months ago.

I curated a live event celebrating black women at the intersection of Women’s History Month and Black History Month. I called the event In Love & Struggle. Side note: the title was my small tribute to the great novelist Alice Walker — 25 years ago, I got her to sign one of her books to me and she wrote “To Rebecca: In Love and Struggle.”

That phrase became the prompt for the series: three nights of performances in which a group of women would deliver monologues or personal stories or poems.

As soon as Brittany submitted her piece, even without hearing her say it out loud, it became clear to me that she was the right person to kick things off.

Each night, she came out on stage in a white suit, her eyes bright and focused, shoulders squared and lifted. She talked about her mother and grandmother, how black women fought for the right to vote, even when white women refused to let us stand with them. Her words rang out like a sermon or a seance, calling upon ancestors to keep us accountable, to keep us together, in community.

This is how Brittany spends her days — how she spends her life — and now that we are all in quarantine, I wanted to hear from her again, to learn how she is using her platform to keep us all together, to keep loving us and us loving each other, and our blackness.

Brittany: My platforms for me are an opportunity not just to continue to be an educator, cause that's truly what my background is - I was a third grade teacher, but Facebook was a bevy of misinformation about Covid 19. About what its roots are, there were conspiracy theories about it starting in everything from the 5G in your phones to Bill Gates being the architect of this pandemic.

There were lots of myths about who could get it and who couldn't - because to be very clear, everyone can get it. And there were ideas circulating around the idea that black people weren't getting it because, you know, people were looking at a low number of cases in Africa at the time.

They were all of these kind of wildly spun conspiracy theories that I was very clear, we're going to leave people in jeopardy, in danger. And we should be clear - people are not attracted to these conspiracy theories because they are ill equipped or low information or not smart enough.

There are lots of reasons why marginalized communities, black communities, communities of color, are suspicious of the medical profession, right? We look at, uh, the Tuskegee Experiment. We look at the fact that the so-called father of gynecology literally created treatments for women by performing involuntary surgeries on enslaved black women, right? So, I mean, the distrust of the medical field is justified and historic.

So I kind of went on there, I was like - I love you all, you all are my community, and I want us all to be well. So, as somebody who is responsible for reading the news and sharing the news all the time, let me make sure I'm doing that here too.

Rebecca: Did you find that it was more elders or everybody that was sort of across generations?

Brittany: You know, it was across generations. I think that when I have been engaging with my elders in particular, some of it has come down to just how resilient black people have had to be throughout time. And therefore, we've got elders who are like, look - this didn't take me out,

and the depression didn't take me out, and Jim Crow didn't take me out, and, X, Y and Z didn't take me out. I'm still here, so this isn't going to take me out either. And I'm like, I want that to be true, therefore I need you to take these precautions. So I, there, I think there was really a generational aspect to it.

Rebecca:Yes. And when I think about that history of resilience, I feel so proud and I think of that refrain I hear in times of both joy and crisis: I love being black, I love us. But I’m also reminded that that pride can cause a fissure of sorts between communities of color. Have you seen that in response to this pandemic?

Brittany: I think what I have personally witnessed is something that I'm really grateful for in that there is an acknowledgement of a common human condition right now, while there is simultaneously an acknowledgement of how inequality is exacerbated in moments of panic and global crisis, right? So, as an example - today, I was going through the detail of the relief bill that the Senate had just passed. There are all kinds of inequities that are continuing to be laid bare during this crisis and by that bill. And so I started to bring some of those things up on Twitter.

What I found was that people who are interested in eradicating inequality always, and especially now, were interested in all of it. And I think that that speaks to the power of the human spirit to be able to say. We are both all one and we all have unique challenges unto ourselves. And we can do two things at once.

We can walk and chew gum at the same time. We can make sure that there are certain things like testing and treatment and, and, economic relief that are universal for every single person who needs them. And we can also pay special attention to the folks who have to have a special call out. Otherwise they will continue to be disproportionately impacted.

Rebecca: Right. Right. Another tweet you wrote, “I saw a lot of folks making jokes on Sunday. Pastors are still asking for those tithes, ain’t they?” You wrote: “Churches employ people who need their paycheck too. Churches often stand in the gap in emergencies where social services don't. Most are not Joel Olsteen.” Can you talk a little bit first about your own relationship with the church.

Brittany: Yeah. You know, I, um, I am absolutely a child and a product of the black church as an institution. And I discuss it as an institution because it is both a spiritual foundation for me, but it is also an outlet of social justice. And those two things are deeply interconnected. So my father was a pastor of a very large historic black church in St Louis called Central Baptist church.

My mother is an ordained minister. She was ordained several years later. My brother is a licensed minister and he went to divinity school where my dad went. Um, and I consider justice to be my ministry. So this is very much the family business. And it is such because my father was a black liberation theologian. Black liberation theology can help a black person, have mindsets of freedom and take action toward freedom was the tradition that I was consistently raised in.

And I centered that not just in, you know, the words that I read, and the things that I studied in Sunday school, in the songs that we sang, in the history that I learned, but also in the fellowship and the gathering of other black folks. That in a single church service, there could be somebody laying hands on the sick praying for them to be healed, and somebody passing out backpacks to kids because school is about to start and they need school supplies. And my dad preaching a sermon about what it looks like to be free in heaven and on earth. Right. That that could all happen in the span of two hours in one place.

Rebecca: Yeah. Right. Because it's not necessarily about, you know, this almighty white guy in a chair. It's about essence really, right? It's about what's at the core of who we are as human beings, and that's who we can be to each other, right?

Brittany: Yeah. And,what we can accomplish together. And listen, the black church and the church broadly is not without fault. We need to be very clear about that. There are far too many misogynistic, homophobic, transphobic messages that are being shielded in improper theology. And I think that that's critically important that we acknowledge that, that we own that, that we correct for that within the church.

It took my husband and I a year to find a church that was both affirming of women and LGBTQ folks and also culturally black. It felt like we were looking for a needle in a haystack, but there is work to be done inside the church to correct it so that it is properly edifying all of God's people. like that is, that is critical.

And so I understand why people are suspicious of supporting the church in a moment like this, but the truth of the matter is, the number of families I know that experienced their house burning down or their child not having enough money to pay the tuition bill in college or the families that would have gone hungry if it weren't for somebody's church house. The wives that would not have been able to leave abusive relationships had it not been for the church house. I know too many of these stories personally. And I know too many examples of times when churches who properly understand their position in society as a service to the people have stood in the gap between people's needs and their social services that they were able to access.

For me to think that without churches, we're going to be able to meet every need in a time like this. Churches, their food banks, their pantries, their counseling services - A lot of them are really necessary for people. And I respect people's decision to worship whomever they weren't or not worship at all. So I don't want to commingle the wrong things here. But I do think that it is important for us to recognize that there is a role that religious institutions are playing, especially in low income communities and communities of color.

Rebecca: You said in an article, because of them we can - faith without works is dead.

In our household, we do our best to pray for those who go without, then get to work playing our small part to create justice for all of us - however we can. It's not about us, it's about our community. In these terms what does community actually mean to you?

Brittany: I mean, Rebecca, this time is really reminding me that there are no strangers.

Right? I mean, if we, if we, if we think about how Covid-19 has spread, it has spread between people that we would deem, on a surface level, as strangers, right? Folks past each other in a coffee shop, People who are opening the door of one after another, people who are sitting on the same subway car, people who in other circumstances have no connection.

And suddenly if you are finding yourself in the extremely unfortunate position of having gotten Covid 19, you are then retracing your steps and thinking about all of these people whose names you don't know, whose faces you might not remember, but who you are now intimately connected to. Because you have shared something that can harm both of you.

If we have the power to share things that can harm us, then we have the power to share things that can heal us too. And so I'm just reminded in this moment that there are no strangers. That we are all intricately connected in all of the ways that Dr. King described before. And if we choose to, we can leverage those connections to ensure that each one of us experienced justice in our lifetime. And so for me, community means being intentional about that. It means, you know those moments when I'm in the grocery store and I'm feeling that panic, and I've looked in four different grocery stores for canola oil because if I have to learn how to make my own bread - I need canola oil, and I finally get to the Safeway, and there are two things of canola oil on the shelf.

Deciding to take one, because me and my husband are a two person household. Instead of deciding to take two and not think of the person's coming after me, right? It is those small intentional acts of community, of a recognition that I need to care about the person coming after me because their fate is my fate too.

Those are the things that we need to be thinking about now and wrestling with now and deciding to do with intention, not just during moments of crisis, but when we emerge from moments of crisis.

Rebecca: So those moments of intention, you know, are individual moments that have broader, repercussions, of course. But how do we, you know, you talked about the - if we have the power to harm, we have the power to heal - how do we harness that power? How do we harness those individual moments?

Brittany: I think it's about surveying your direct field of influence. I have so many people who ask me the question all the time - how did you get started in activism? How do I get started in activism? I got started in activism A) because like my parents raised me to do this and I really didn't have a choice. So my very first protest, I was in strollers.

But the first time I ever remember really choosing an activist lifestyle was when I saw something happening in my class, to a classmate of mine that I didn't think was fair. I was in the third grade and there was, I went to predominantly white schools because that was my best shot at a strong academic upbringing. And so I was one of few, if not the only black kid in my class, often. In the third grade, there was a young man named Christian who, uh, joined the school. And because I went to school with mostly wealthy kids, and because, many folks in my family and my own family and people I went to church with are not wealthy. I constantly felt like I was experiencing that double consciousness that DuBois talks about. Not just in matters of race, but also in matters of class.

And Christian was being raised by his grandmother. He lived, um, in a low income community. When he came to school, he looked so scared and then he locked eyes with me. And I was like, okay, well the Christian is the person I'm going to sit next to at lunch, right? And I clearly wasn't translating it in this language then, but the idea that somebody who is different from everybody else wouldn't be treated well, bothered me.And instead of running away from that feeling, I ran toward it and decided to leverage it to fuel something, right? And that is the intentional thing that every single person can do. You can look at your sphere of influence, your family, your children, your elders, your block, your church, your book club, your mosque, your workplace, your team, your kid's school, your kid's soccer team. Those are all places where you exert influence.

That’s Brittany Packnett Cunningham - coming up - how the Coronavirus could impact policing in black communities. That’s in just a minute.

Rebecca: You know, we set out to create this podcast as a series of essential conversations in a pivotal year for America, that pivotal thing being the upcoming presidential election.

But now, you know, we have another pivotal thing. This pandemic is truly pivotal. So have you thought about how it will impact the election?

Brittany: I had a super long conversation with my husband, Reggie this morning. We've been married for like, we're coming up on four months. So the phrase, my husband is still weird to me. So I think I keep saying it like, as practice. Like - get used to this! Um, but we had a really long conversation this morning about it. Because there are so many permutations here, right? There is a path that says: we will be back to some semblance of normal life by the summertime, those postponed primaries can continue, the Republican National Convention and Democratic National Convention will go on as planned. Maybe with some alterations, but as planned. And we walk toward November, continuing to flatten the curve and everybody can go vote. Hopefully with an increase in voting by mail and early voting so that we can space people out and keep them healthy, right? Then there is the permutation where we've got a great summer, but there's another peak in the pandemic in the fall, and we have to look seriously at whether or not November is actually a safe national election day, right? There are possibilities where we don't get the summer back at all, and the nominating process is completely altered and we have no idea how to ensure that folks feel like their voice was heard in deciding who would be the democratic nominee to face off to Donald Trump. And beyond that, deciding who the next president would be, right? I think what I am paying most careful attention to is how we are fighting suppression in this moment. As I shared in my piece In Love and Struggle, voter suppression in America, suppression specifically of Black voices, marginalized voices, poor people, indigenous people -

that is as American as Apple pie. And it has been going on for a very long time, and we're having to be diligent about fighting it every single day with every single election cycle, not just federal, but local and state, right. Now we have a situation where that suppression intentionally and unintentionally can be heightened. And so how do we make sure that we do not create a false choice of keeping people healthy, or letting them be heard democratically. There are solutions to figure out how we do both of those things. I think that nationwide voting by mail should have been instituted a long time ago. The postage should be prepaid. Um, there are lots of ways in which States and the federal government can decide to make this thing truly equitable.

The problem is, for too many of them, it's actually not in their best interest to do so. And so I continue to worry about, and focus a lot of my energy on how we correct for the existing suppression and how we, uh, guard against additional suppression that can happen because of these unprecedented circumstances.

Rebecca: Um, you know, so much of your work is about police brutality and racial profiling. Is there a nuanced conversation at all about how this pandemic has impacted policing?

Brittany: I think that it's a conversation that is still in development. I think that activist spaces, most certainly because we have been doing a lot of this research and speaking out on this for a long time, and communities of color more generally black and Latin X in particular, and indigenous communities in particular. Because we are already so tuned in to police violence, a lot of us are thinking ahead about what it means if we end up in the state of lockdown, such that there is a police officer at the end of my block asking me where I'm going. Demanding that I pull out ID. Right, right.

Rebecca: I had a girlfriend say, she was at the park with her son the other day and a police officer said, what are you doing? Like, that's already happening.

Brittany: Yeah, exactly! So there is already a heightened sensitivity to what it can mean for that to happen. There's also, I think an understanding that everyone is not going to make the right choice for themselves and their neighbors and stay inside when they don't need to be outside,

right? So, I think that that conversation is developing because it is really tough to let both of those things be true. That we do not want to increase experiences of police violence in our communities, and we also want people to be healthy and well, and to do the things that will help their neighbors be healthy and well. So I think that that conversation is still in development. What I do think is critically important though, is that, um. We pay attention, not just to the kind of experience of policing that we have on our streets, in our neighborhoods during this, but how the Department of Justice operates during this. Because these are the kinds of crises where people see their right to privacy, um, and their right to human dignity, superseded by governments who are, and administrations rather, who want to reach a long arm into your life, and leverage the crisis in other ways, right? I mean, we saw that after 9/11. We now all know what Dick Che- we know at least plenty of what Dick Cheney was doingI'm sure there's plenty of stuff that we still don't know yet.

And so I think that in that way, there is a nuanced conversation about what justice looks like right now, for everyday people and watching very closely what the Department of Justice is trying to do. The other piece, most obviously, is thinking about people who are incarcerated right now and how unsafe they are. They were already unsafe. We already saw a number of deaths in Mississippi prisons, in particular due to overcrowding and the kind of violence that people were experiencing in there. There are actually 18 incarcerated people who died between, I want to say December 29th or 30th, and the middle of February. There were some days where there were multiple people who died in a single day because the conditions in there are so inhumane. And now we are seeing so many people. Who did not have to be in jail, who are in jail because they can't afford bail, and they have not been convicted of anything.

People who are nonviolent offenders, people who are elderly and have served out the majority of their sentence, but they're still being held. I mean, there are so many folks who are being put in harms way in these tight and crowded conditions, when they don't have to be. And I'm hopeful that this moment will help us realize and get serious about all of the things we were once told were impossible that simply are not.

It is totally possible to dramatically reduce the prison and jail population in this country within a matter of years, not decades, years. It is totally possible to figure out how to get people a universal basic income, not in decades, in a matter of weeks and months. It is completely possible for us to figure out how not to evict people and cut off people's essential utilities, uh, in a matter of days, not weeks or months, right? So these are certainly unprecedented times, but unprecedented times call for us to have unprecedented imagination. And it is our choice as to whether or not we will apply that imagination, not just to times of crisis, but to times of restored normalcy as well.

Rebecca: It is heavy, man. It is really, really heavy. How do you not get overwhelmed? And you have to take care of yourself for yourself, right?

Brittany: Absolutely, Absolutely, a hundred percent.

Rebecca: And, and what do you do to take care of yourself? What is your self care?

Brittany: I saw somebody say on Twitter, and for the life of me, I can't remember who that person is now. They said that true self care is curating a life from which you don't have to constantly escape. And that for me was a game changer. Because previously, whenever anybody asked me this question, it was - I go to get my nails done, I stopped answering emails at this time, I have date night with my, at the time fiance now husband. All of those mechanics are helpful. But it's actually about looking at the entirety of my day, my week, my month, and saying what has to exist here for me to be my best self. Not just my best laborer, not just my best worker, not just my best thinker, and not just my best writer, not just best at whatever I am looking to produce. But be at my best period. Be at my most joyful, be at my most rested, be at my most whole, um, be at my most happy. What are the things that are necessary for me to feel like that consistently over time instead of in spurts? How do I curate a life that I do not have to constantly escape? That takes a lot more planning, but in the end, it is absolutely time well spent.

Rebecca: Yeah. And I think it also comes with living, you know? Comes with realizing that, you know, the things that you curate, the things that you choose to have in your life then doesn't matter like that your apartment is tiny. Like ours is. You know, like my husband and I recently rediscovered that we actually really like talking to each other when we're not rushing to be somewhere or in between meals or taking our kid to his basketball practice.

And that's really - it's a lovely thing to be able to say in this small space, the three of us, we enjoy each other. I mean, obviously we're getting on each other's nerves as well. What have been sort of the discoveries and or challenges?

Brittany: Newlywed and quarantined. Who would've thunk it?

Rebecca: Hey that's a reality show right there!

Brittany: We've been putting up clips, you know. We like, joked around on Instagram and now it's become a whole thing. That like, every day we're like “tonight on Newlywed and Quarantined”.

Some of what I have learned about him, I don't think I could have learned if we were not in these circumstances. And some of it is like, you know, cute, fun stuff about how we can make our own fun, and how apparently we can play two person UNO until four o'clock in the morning, which we did last night. Um, and I still hadn't even come close to besting him in most of the games, which is very frustrating and I've been trying to figure out how to do that.

Um, but we also just had some really intimate conversations as we've come to learn each other. About like - what he needs to have a well curated life and what I need to have a well curated life and how we're just continuing to refine our edges so that they fit better with one another. There have been things that we've shared that I've just really grateful for, that I don't think would've happened if we didn't have this much intentional time together.

Rebecca: I mean, as somebody who's constantly on the go, I mean, when I saw you a month ago, you were like, you had come from here, you're going there, you're about to go here. I mean, what must it feel like to just sit your ass down, and not go anywhere?

Brittany: I'm not going to lie to you. I'm not happy about the reason that I'm having to do this, but it has felt really good. Like, I can't even lie about that. My body has basically been telling me, thank you for sitting down.

Um, and I, you know, as a person that faith believe that there are times that God will stop you and say. You were prioritizing the wrong things. You are not prioritizing the taking care of the temple and the vessel that I gave you, in your body. And so you're going to have to recalibrate here. too often.

I feel like a pinball, so I feel like I'm bouncing around from place to place. And the force that is pushing me is not even me, right? That there's somebody at the back of the machine who's like pushing me in this direction and that direction because I'm a people pleaser.

So you're pulling me over this way and you're pulling you over this way. And I never pulling myself back to a neutral position so that I can reset. And I am, I'm trying, much better to be a person in alignment, more often than I am not.

Rebecca: Yeah. And so to be that person in alignment, you have to be still, maybe, right? And so if you're, if you're talking about who you were before, who you have to be during this time and who you will be after. I think it's hard to imagine. It's hard to imagine who we will be after. You know, I keep thinking of it in such a, in an intergenerational way, you know, thinking about my teenager who has gone through waves of, you know young people can't get it to, Oh my God, mom, don't touch anything at the grocery store that you're not gonna actually buy. You know, to like trying to do his online classes and not be able to see his boys and play basketball and, you know. And then I'm thinking about the babies who, who moms and dads and, and are home with constantly. I mean, I remember when my kid was a toddler. It's a long ass day without a pandemic, you know? It's hard to think about who will be, um, after this. But in a best case scenario, what do you think?

Brittany: In a best case scenario, we won't have wasted the lessons that this time is forcing on us. Um, in a best case scenario, I think we will recognize and act upon the fragility of human life and understand that people deserve protection.

I'm hopeful that we will understand that, uh, survival is the floor, and thriving should be the ceiling because now we're all in a state of survival, right? There are people who were constantly living their lives in states of survival. Racially, economically, physically, there are people who the best they could do every single day was to survive.

And there were folks who would look at them and say, that's your bed. You lie in it. That's a choice that you made, and at least you're surviving. Now that everyone is forced to be in survival mode, folks realize that that is no way to live, right? And so I think that, I'm hopeful that one of the lessons that we learned is that.

Well, we should be doing in this world is not trying to get to a place where everyone can survive, but get to a place where everyone can thrive. Because every single human being actually deserves that. And I believe that they will make better choices for themselves and other people if they are able to thrive.

Um, I'm hopeful that we'll learn some basic lessons, like I said,about consumption, about community, about remembering that we are a part of a community, no matter where we are, if you're at home or if you're in a room full of 50 people I'm hoping that people will remember how to connect. And lastly, I hope we all pay teachers better after this.

Rebecca: That's right. Oh, I appreciate you so much, Brittany.

Brittany: Oh, I appreciate you. Thank you for this conversation. Thank you for this podcast. I can't wait to subscribe and listen and get some joy and some insight during all of this wildness, so thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

Rebecca: Thank you. Thank you.

That’s Brittany Packnett Cunningham. You can hear her every week on the podcast Pod Save the People - and I highly recommend following her on twitter. She’s @MsPackyetti.

Come Through is a production of WNYC Studios.

Christina Djossa and Joanna Solotaroff produce the show, with editing by Anna Holmes and Jenny Lawton. The show is executive produced by Paula Szuchman. Our technical director is Joe Plourde, and the music is by Isaac Jones. Special thanks to Anthony Bansie.

I’m Rebecca Carroll - you can follow me @Rebel19 for all things Come Through - and - if you liked the show, please go ahead and rate and review us. Until next time.