9. Bassey Ikpi Didn’t Enter the World Broken

Before we get started, I wanted to just give you the heads-up that in this episode, we talk about suicide.

I’m Rebecca Carroll and this is Come Through: 15 essential conversations about race in a pivotal year for America.

At what was probably the darkest moment in my life, I experienced a bout of depression that I couldn’t get out from under.

I just felt kind of done. Done doing life.

This was about 25 years ago. I’d just moved to New York. I was living with a close girlfriend who came home one night to find me in a really bad state, and she said, “Oh girl, honey, listen — you have too much to do to be done. Too many books to write, stories to tell, children to love.”

Here we were, two black women in our early 20s, both with promising jobs, trying to carve out lives for ourselves in the big city, and I was ready to hang it up. That’s what depression does. It doesn’t care about your promise or your ambition.

My girlfriend told me that I needed to get help, and to be perfectly honest, I had no idea what she meant by help — like, a therapist? “Yes,” she said. “Exactly like a therapist.” I did get help. And to this day, I believe that my girlfriend saved my life that night.

Talking about mental health is hard -- especially in the black community - where it has been stigmatized in a very different and potentially more dangerous way than in the white community. But it’s also where the conversation is most needed. And more specifically, among black women. Because we are suffering right now. Right this minute.

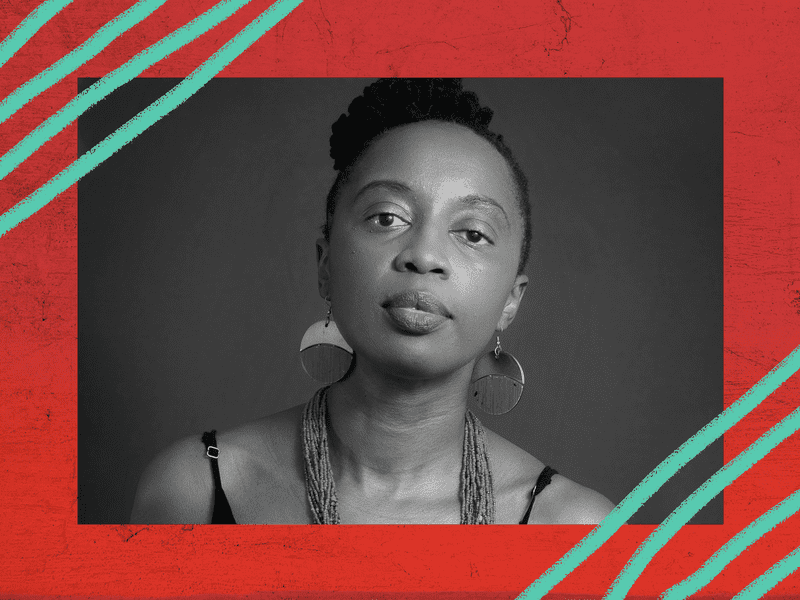

That’s why I’m so grateful for women like Bassey Ikpi, who are willing to go there and talk about it. Bassey’s career began to take off with her work as a performer on HBO’s Def Poetry Jam. Her book, called I’m Telling the Truth, But I’m Lying, became an instant New York Times Bestseller after it was published last year. In it, she describes her own personal, harrowing account as a black woman dealing with mental health. Bassey writes about how she struggled with a heaviness and worry growing up as a young girl in Nigeria - feelings she wouldn’t have language to identify until over a decade later. In 2004, Bassey was finally able to put a name to what she had been experiencing all of her life, when she was diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder.

I interviewed Bassey a few months ago - and we’ll get to that conversation in a minute.

But now living in the age of Covid-19, a virus that is disproportionately killing black people, I feel like there’s this whole new influx of trauma we have to endure - the disease is plowing through our communities, while we’re cut off from resources and family support that we normally rely on to keep ourselves steady. And so for anyone with a history of trauma - that trauma is resurfacing in really complex ways. So, before playing you that initial conversation, I wanted to quickly check in with Bassey and hear how she’s doing - right now.

Bassey: Um, I am a lot better than I was just a few days ago. Um, last week was very, very difficult and I think that for me, my default, um, I tell people that I have resting smile face. Um, and so my default has been, “It's not great, but it's okay.” Uh, last week tested that to the point of everything that's happened or hasn't happened for the last two months came to a head in the form of all these black people dying. You know, like the personification of all of the collective, you know, emotions that we've been holding with no place to put it. 'Cause you can't be mad at Coronavirus. I was telling my therapist when this first started, when I can't get out of bed, when I can't leave the house, when I feel so uncertain and untethered, it's usually because it's depression. So to not feel depressed, but live in an environment that is fostering depression is very confusing. And for me, it all had a place to go last week.

Rebecca: And so in that instance, how did you take care of yourself?

Bassey: I gave myself permission to grieve without having to quantify it. I didn't need to explain why my heart was broken for the recent murders of Ahmaud and Eric and Brianna, and the recent deaths of Little Richard and Betty Wright. And I was allowed to just feel that. Um, I also gave myself over to community. One of the most difficult things for me, again, in this experience is that we as a community aren't in a position to mourn and grieve the way that we're used to. So having to recreate that in the space that we're in is something that I took to heart. You know, the Erykah, Jill Scott conversation on Instagram did something to my spirit that I didn't know that I needed because it recalled a different time. It recalled an easier time for me, especially early two-thousands Brooklyn. I gave myself over to that memory and to those memories and I called people and spoke to people who, who could reminisce about that time with me. That was important to me. Music, I played all the songs that reminded me of the people that we lost and gave myself permission to celebrate them in the way that I knew how to.

Rebecca: So I, you know, we, we live… My husband, my son, and I live in a very small apartment and we're all really trying to hold each other up and not go crazy and keep creating and talking. But I just, I'm thinking of that kind of, how close and easy it would be for me to lapse, you know, um, into that time of which I haven't felt for a very long time just of not being able to move. But I have, I have this mantra for myself, which is just to cultivate gratitude, to do the quarantine rules and keep it moving. Do you have any kind of mantra that's helping to get you through?

Bassey: For once I don't have, you know, words that I repeat. Um, but I've started taking really long walks. I'm not an audiobook person, but it's become almost an, it's become a meditation for me where I just, I press play and I just start walking. And it's almost like a conversation with somebody who likes to talk a lot. Um, and it gives my brain space to just rise and fall and settle wherever it needs to settle. And, um, it's gotten me back into working out because there was a time very early in this when I would wake up at 6:30 and 10 o'clock would roll around and I'm still in the bed as though, you know, I just could not bring myself to get out of bed. And so training myself to wake up, walk across the room to get my medication instead of keeping it next to me, take that while I'm up… Okay, well, I'm up now. Go to the bathroom, I'm in the bathroom now. My, you know, workout clothes are hanging on the back of the door, put them on. You know, like, these are the things that I used to set up for myself when I was deep in depression. So I'm using those same tools to get me out of this, I don't know, spiritual, environmental depression. Um, so that ritual for me, the walking and then coming in, and then, you know, doing a medicine ball, things that, that, that let me close my eyes and just give into the repetition of moving up and down or putting one foot in front of the other.

Rebecca: And what would you advise or what, what would your advice be for folks who are really struggling right now?

Bassey: My main advice, ’cause all the stuff that I'm telling you, I've only been doing for the last week, which means that for the last, yeah, so that means for the last, uh, month and however many weeks, um, I wasn't doing that. But one of the things my therapist, and we were still having, um, tele sessions, was that to remember that this is an unusual time. There's nothing ordinary about this. There are no rules. There are no tools. What you need to do is find the thing that you can hold onto. And I mean that in a sense that I would, you know, speak to my therapist and tell her, “I'm not motivated. I'm not productive. I'm not this, I'm not that.” And then she's like, “Well, what are you doing? You know, when you say that you can't get out of bed, are you just lying in the bed and staring at the wall?” And I'm like, “Well, no, I'm on, you know, I've got my phone and I'm scrolling through through Twitter or TikTok, which I've just discovered.” She's like, “Well, are you laughing?” I was like, “Well, yeah.” “And are you having conversations with people via Twitter?” “Yeah, I'm doing that.” She's like, “Well, you're engaging. You're in community with people. You don't like to think of it that way because we've been taught that these things are time-wasters and are preventing us from being productive. But that's actually the way that we're learning to be productive. And just know that you are still a person who deserves to take their time to feel whatever it is they need to feel.”

Rebecca: Yeah. I love that. And I also think this moment, um, which, as you said, and as your therapist said, is, you know, it's happening for the first time. We don't, we don't know what's happening. And so we also don't know what's going to trigger certain traumas we thought were dormant. Right?

Bassey: Yes. Yeah.

Rebecca: What has that felt like for you?

Bassey: Uh, in the very beginning of this, I was numb, um, in ways that I hadn't experienced for a really long time. And what I realized was that we have learned to be busy. Um, we would feel certain things that may be leading to a bigger trigger or a trigger and we'd find a way to be busy around it. To say, “Okay, well I can't do this right now. I need to go about my business.” And right now we have no business to go about. So we have to live with and sit with these things in ways that we never have before. And I think there's something very necessary about that. Uh, something very beautiful about that. And I'm speaking in terms of, uh, you know, nothing that's catastrophic or so traumatic that it's, that you can't drive yourself out of it or you can't pick yourself out of it. Um, but it was important for me to realize that I had been avoiding things because they were too small. Right? I'd avoided them because they didn't seem as serious as the huge depressions and the huge anxieties that I'd learned were the only ones worth focusing on. So it's given me the opportunity to work on the smaller things because they're taking up space too. Um, I read an article, or it was a tweet, very soon after this started where someone was basically saying, “Oh, you know, welcome to our world. This is what chronic illness feels like.” And I thought that was so uncharitable because there’s no superiority in knowing how to deal with trauma. If someone hasn't faced things the way that you have, it's not your responsibility, but it would be a grace offered to say, “Okay, this is new for you, but this is how I've dealt with it in the past. This is one thing you can do to make it just a little bit easier for you. ‘Cause I don't want you to experience it the way that I've known it outside of this.” I've seen, you know, the worst of people ‘cause people will always show up the way that they are regardless of what pandemic is happening or not happening. But I've also seen so much hospitality and grace and, and compassion and empathy being offered to people in order to support them. And that's something that I've learned to focus on too, because I need those kinds of things to keep me motivated. I need to know that there's a possibility that the world will end up better because of this. And last week tested that for me. And I have to re-give myself that, um, that optimism to keep myself moving and motivated. And not giving yourself permission to step away is something that I'll always advocate. You don't need to watch the world burn. Step away. You don't have to stare at it.

Rebecca: And on that note - thank you so much, Bassey.

Bassey: Thank you.

That was Bassey Ikpi, about a week ago.

Now we’re going to jump back in time - to my initial conversation with Bassey, which was recorded pre-Covid. But the story of her life and her work is as relevant as ever. And it’s really inspiring too.

Here’s that conversation now.

Rebecca: So the first line of your first essay in your book, "I'm Lying, But I'm Telling the Truth," which is an extraordinary piece of work reads, “I need to prove to you that I didn't enter the world broken.” What did you mean by that statement?

Bassey: Um, I meant that because of the rest of the book was filled, I thought, with so much chaos and so much, uh, I don't really love using the word “trauma” ‘cause I feel like there are other people who own that word in ways that, that I don't want to, um, to take over. But because during the process of writing the book, I had to uncover so much, that it was really heavy for me that I almost forgot that I was doing okay now. You know? So, um, it was important for me to, as a reminder to myself going forward and then for other people reading it that not only was I okay now, but I was okay at some point. There were things in the middle that got a little bit shaken up.

Rebecca: So how would you describe the way you entered the world?

Bassey: Um, I'd say chaotic. I think that there was a lot going on with my parents that I didn't know and I probably will never know. Definitely came in loved. I never, ever, with all the things that I've gone through, I never felt unloved. Um, I might've felt unliked at certain times, but I never felt uncared for. In the book I describe the many hands that held me and took care of me. They were, I always felt that there was somebody or a group of somebodies who, um, were going to take care of me, which was a double-edged sword, because to feel that lonely, knowing that you're surrounded by so many people, is also something difficult to combat.

Rebecca: And so you were diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 2004. What did it feel like to hear that diagnosis?

Bassey: Uh, it was a relief, um, because I knew that there was something, quote, unquote wrong. And I knew that there were things going on in my life that I couldn't control. So I was grateful to know that there were other people, or at least someone who knew of this thing that I was going through. It wasn't that unusual. Uh, but I was also scared to death because those aren’t the words you want to hear, especially as a black woman, especially, you know, 2004 where we weren't having conversations about mental health. We weren't as… Uh, introspective in that way was very much, “Oh, I don't want that. That person's crazy. Get away from me.” That was the thing I was most afraid of. Uh, being thrown away because of this thing that I just discovered that made me feel good to know. But then, you know, that fear of being thrown away is something that I think that a lot of us have. And I imagine just from stuff that I've read from you that this idea that people can just abandon you or just leave you at any chance. That's something that follows me to this day.

Rebecca: Right. No, I was going to ask. Like, since the diagnosis, have you experienced feelings of dismissal or discouragement, um, regarding the diagnosis and how you're going to move forward with your life?

Bassey: Definitely, yes. Uh, in relationships, uh, with, with men. I've had conversations where someone has done something that is infuriating and anybody would be mad. And then when you express that anger, “Oh, you're being bipolar. Oh my God. Is that the bipolar talking?” And it's like, “No, I'm, I'm a human being. And what you did is messed up. And I'm upset about that.” And for, for a while I got very quiet about expressing anger because I didn't want the label of, of what people think it is to be bipolar, to have bipolar disorder. When it comes to medical professionals, what's interesting is that I was very, very fortunate to have my first therapist and first psychiatrist really arm me and prepare me and teach me how to advocate for myself in ways that I've carried on to this day. But in October I was hospitalized for, um, something called pancytopenia, which is like a severe, severe form of anemia where all your blood cells are just low. And I'd been feeling unwell for a while, but I've been so trained to focus on my mental health that my physical health was just doing all kinds of things. And getting older, I was like, “Well, I guess I'm out of shape. I haven't really worked out that much, and you know, I'm over 40 now, so I guess it's just the way I feel.” But I would go to the doctor and I would tell her, I was like, “Listen, I’m having trouble breathing, walking short distances. I'm not feeling great. You know?” And because this doctor had my full medical history, she blamed it on anxiety. She just kept dismissing it and dismissing it to the point where I go to the ER because I'm just like, “I can't function.” And I went to the ER and I was immediately admitted and given an emergency blood transfusion. And I’d been feeling unwell for over a year, but this doctor had decided that because she knew my mental medical history, that she didn't have to take care with my physical. And that's something that was very jarring to me, that I was actually very upset once I thought about all that could have happened just because she decided that she didn't want to take me seriously.

Rebecca: And so has your own language around your diagnosis changed in the 15 or so years since you were diagnosed?

Bassey: Oh, absolutely. Um. I, I'm very careful to say that, "I have depression. I have bipolar disorder." I don't say, "I am bipolar." Or, "I am depressed." That language is really important to me because I don't want to be intertwined with it so much that it becomes part of my personality.

Rebecca: Do you think it’s possible to separate the diagnosis from your lived experience? Meaning, once you understand what the diagnosis is and what you have, does that make your life any easier to negotiate?

Bassey: It did for me. I, I am able to check myself in ways now that I, that I had never done before in my life. I'm able to acknowledge that there’s a depressive coating that isn't necessarily part of my actual skin. I didn't mean that to be as poetic.

Rebecca: I’ll take it.

Bassey: Um, yeah. So I’m the healthiest now that I've ever been in my entire life. And I say that often because it doesn't mean that anything went away. It means that if I go too many nights going to bed at two, three in the morning, I have to be very careful and check in and say, “Is this insomnia sneaking in? Is this hypomania sneaking in?” And I have to make adjustments. You know, I have to go to bed a little bit early. I have to, you know, do things that other people take for granted in order to make sure that I am not veering one way or another. Um, there's a very tight, tight rope that I walk, um, in order to make sure that I stay balanced, uh, making sure that my doctors are aware of everything that's going on to the point where it's like, “All right, you're good.” You know? As opposed to me trying to figure it out for myself. My family is in on it. I live with my parents and my son because for my son, I don't want him to be responsible for my moods. Therefore, he needs to have other people in the house that surround him when I'm not able to do that.

Rebecca: How old is he?

Bassey: He just turned 13, God help us all.

Rebecca: Listen, mine is 14.

Bassey: Oh my God. And I talked to you about how that works ‘cause I am…

Rebecca: But in terms of your own moods and, you know, keeping yourself in check and your accountability, I mean, you know, that as a parent, as a mother, you know, there's a whole different level of accountability.

Bassey: Yes.

Rebecca: And so is that something that you think over in your head at various times during the day, at night or with, or in conversation with your child?

Bassey: All the time. Um, I've spent so much time being afraid that I was going to break him in some way that I don't think I realized about a year or two ago that I wasn't arming him properly. I was keeping them a little bit too protected. Actually, he started therapy about three or four months ago, just as a preventative measure, just so he has someone that's not me to express whatever fears, whatever questions he might have, to help him understand some of the… Because he was very young the last time I was hospitalized. He was nine the last time I had a deep depressive episode that I thought that I would never get out of it, and I mistakenly thought he was protected from that, but he sees it, you know, he felt it and I had no idea that the thing that I was running from the most, which is him being responsible, had taken on another form. Um.

Rebecca: What did that look like?

Bassey: It looked like even though I said I didn't want him responsible for my emotions, he did track when, when I was, you know, happy. You know, he's an athlete and a star soccer player, like, unbelievably good at soccer. And because I wanted to be present for him, I would get excited when he scored. You know, I’d get excited when he did, like, a really great play. I was able to access that in, like, in the deepest of my depression, be very happy for him when he did something well to the point he felt like he always had to do something well or else I would get upset or I would fall back into the quiet. Because at the end of the day, regardless of whether how many people you surround them with, you're still mom. You're still like a connection there that even if they don't say anything, it's present. And, you know, he goes to therapy once a week and every once in a while he'll ask me to come into a session with him. And there's so much about him wanting me to trust myself and trust that I didn't break him, which is something that I'm very grateful for. But on the flip side of that is that I have a kid who is more empathetic than any grown human I, I know.

Rebecca: I was about to say. I mean, he sounds extremely mature, emotionally mature, which for a boy I have to say is pretty impressive. But also, did he go to therapy just willfully?

Bassey: Um, I asked him a couple of times over the last couple of years if you wanted to go. But there was a time, um, last year when I asked him one day and he was like, “Alright, cool. I'll try it.” And he had a lot of questions, like, on the drive there. And then after the first two or three, he stopped wanting me in there with him. And I noticed anxiety in him from when he was five years old. When he was five years old was when Trayvon was, was killed. And I remember him standing in front of the TV in the family room shaking. And he's five and I'm trying to understand what he's seeing and how he's processing it. And from that point on, I realized how nervous he would get in different situations. I spotted the anxiety and, and I wanted him to know that that was something that didn't have to be a regular part of his life in that it didn't have to control the way that he saw himself or the way he moved in the world.

Rebecca: You know, I had a similar experience with my son when Mike Brown was shot, you know. And he would have been, I don’t know, eight then, and said, “Are you going to get shot?” ‘Cause you know, ‘cause he sees me and then he's like, “Wait, am I going to get shot?” Um, and the anxiety is sort of amped up by social media. And you have had a really interesting relationship with social media, right? You in 2018 was it that you went off social media entirely?

Bassey: Uh, yes. I was off for almost a year, but it was primarily Facebook and Twitter. Um, Twitter was the thing that changed me the most, as far as going off of it, because I went on Twitter when I was at a very, very low point in my life. I was having a mixed episode. It was my last hospitalization in 2010 and I would just pour my feelings out. Like, just tweeting fast and furious and, um, ‘cause I was having a manic episode. And it helped bring this community to me that I didn't know existed. People from all over the world who were able to identify with some of the things I was talking about and I didn't feel quite as alone. But the flip side to that was that I felt this need, especially as politics got ramped up, to share my thoughts on things before I actually thought them through. Um, I had opinions on things that I knew nothing about, but because of the rapid nature of things, I was just talking and talking and talking. And I realized looking at it that I wasn't giving other people grace because they weren't as quick as I was to come up with something off the top of their head. Um.

Rebecca: I mean that’s what Twitter is.

Bassey: I didn't want my Twitter personality to be my personality.

Rebecca: Did you feel like you were mean or?

Bassey: Oh, no, no, no. I was, no, I was never mean. I wasn't mean. I just didn't want to be that vulnerable all the time. I didn't want to be responsible for that. And I felt like as I was talking to people and building this community, I felt that the community started changing in that people started to identify themselves as the illness as the, uh, the thing that I was working so hard to make sure didn't become a part of myself.

Rebecca: Right.

Bassey: I don't know if that's clear. Does that make sense?

Rebecca: It does make sense. And it's all, I mean, it also just speaks directly to, you know, trying to figure out ways to use social media in a way that is healthy. You know, particularly in this regard of a community that talks openly about mental health issues. But also for black women, you know, I mean, Twitter has been an amazing platform for me, certainly, as someone who grew up without black women around me. It's like, I feel that it's a necessary thing for me in some ways. But then there's that question, right, of the “overshare” or the “putting yourself up out there too much.” So how did that affect your healing, your mental health? Or your day-in-day-out? Or, has it?

Bassey: Um, what I discovered was I was just putting things out there, but I wasn't doing any work to heal myself. During that time I wasn't seeing a therapist, um, when I was doing the most oversharing. And it just felt like I was just heavy ‘cause I was putting things out, but they just kept coming back to me even heavier and weightier than before. And I didn't want people to think that the way they manage their own health was just by talking about it and just leaving it out there for the world and just leaving it out there because it's not safe. You know, when I started Twitter in 2009 and then again in 2010 it was a much smaller space. So you didn't have trolls. You didn't have people who's, who only got online to say something terrible to you. And that's not safe, to be going through something and pouring your heart out and then having strangers, people who don't care, don't know, don't have to care, saying terrible things to you. I didn't feel like that was something that I wanted to promote. What I started doing was I'd see someone who looked like they were struggling or looked like they were quote,unquote oversharing, and I'd slip into the DMs and I’d say, “Hey, are you okay? Do you need something outside of Twitter to support you? I've got numbers. I've got a phone number.” You know, I was doing that a lot because there were more people sharing than there were people helping.

Rebecca: Do you think, though, that social media platforms, I mean specifically Twitter, actually undermines or worsens mental health because it encourages this kind of self exposure?

Bassey: Yes, I do. I think there is a category of narcissism that Twitter promotes. Uh, and I don't mean it in the way that narcissism we know narcism to be. But it's this narrow funnel that you see yourself through, and only that through, and you're not able to step outside of it to see where you need to, to help yourself, where you need to go to find the support that you need because people are validating the way that you feel.

Rebecca: And so now that you've been both on and off Twitter, which experience has been better for your mental health?

Bassey: Being back on with the tools that I learned while I was off.

Rebecca: What were the tools?

Bassey: Um, to be quiet, to step back, to let other people tell their stories, um, to not allow people whose sole goal is to irritate people, irritate me. Um, knowing that, you know, what? Now that I'm talking, you're, like, bringing up some other things. I think part of my usage of Twitter was also feeling like no one would know I was around if I didn't tweet. So, now I know that I'm a person who exists on or offline and I'm able to be comfortable with myself offline, enough to leave when it becomes too much. As opposed to staying in the storm because I don't want anyone to forget that I wasn’t there. Now I've got to write this down for my therapist. Thanks, Rebecca.

That’s Bassey Ikpi. She’ll talk about the limitations of Black Excellence - in just a minute.

Rebecca: Have there ever been times, personally, professionally, and now with the success of the book, that you have felt unable to fully commit to or focus on your mental and physical and emotional wellbeing? Has that changed?

Bassey: Oh, no. No, no, no. My, my mental health is more important than anything in the world to me. Oh, that sounds dramatic, but in 2016 I was done. Like, that was the end. I had a date, I had all kinds of things prepared. And once I made the commitment, because my parents and my siblings, like, begged me to just keep trying, just give it, you know, six months or whatever. And I was like, “Alright, fine. You know, I'll just prove to you that I'm going to try, I'm going to double my medication, I'm going to go see the therapist four or five times a week as opposed to twice. I'm going to do all those things and you'll see that it's still not going to work.” And then slowly I started to get better and feel better.

Rebecca: What was the date for?

Bassey: Um, the day that I wouldn't, I wasn't going to be here anymore.

Rebecca: Right.

Bassey: In the book I mentioned a passive suicidality, which is what I've always experienced. It had never been, except for 2016, it’d never been active. It's always, like, “Well, I just won't eat, I just won’t sleep. Whatever people do to make sure that they stay alive, I'll just stop doing that.” And because of that, knowing what that feels like, being healthy is an active part of me. Um, I don't do or experience or, or put myself in situations that jeopardize my mental health, even if I'm not sure. You know what I mean? Like if there's a question that this won't be healthy for me… I've turned down work, uh, because the traveling would be too much and maybe I could handle it, but maybe I couldn't. And the “maybe I couldn't” is enough for me to say no. You know? I couldn't own a Fortune 500 company. The level of…

Rebecca: Did you want to?

Bassey: No, but I mean, I could, do, you know what I mean? Like, you think about the stuff that people are doing and then like, “Oh, I could do that.” And, like, “No, you can't.”

Rebecca: Yeah, I mean, right.That's what I mean, though, about the sort of pressure to be, or to succeed. It’s a confluence of all of these things that then also feed into whatever the diagnosis or the depression or the disorder is. And I think a lot about our mutual friend Erica Kennedy, who was an amazing writer. She wrote “Bling” and “Feminista.” And she was truly a star and really well poised to keep shining even brighter, but still took her own life. And then I think about black girl magic and how there is this sense of championing black girls. And I mean, do you think telling any black girl or woman with depression that she's magical helps anything?

Bassey: Oh, God, you’re gonna get me in trouble. I’m about to get canceled. Um, I, and again, I speak for myself, I had to redefine and redetermine and reassess what success meant to me. Um, I had to take control of the idea that somewhere along the line I had failed. Um, I dropped out of college because I, I know now that I was depressed, but I, at that time I thought I was just lazy and, and, you know, really smart in high school, but kinda dumb in college. That’s the way I felt about myself. And, I'd held that. You know, it's been 20 plus years. I've held not having a college degree. Even though I've talked game about, “Oh no, you don't need it. I'm cool, I'm good,” it's still been a source of shame for me. So all these things that I'd held on as shame, that I smoothed over with varying levels of success, I had to go back and dig through what other people thought was success go to the root of when I thought I had failed and made sense of what it was. Had I continued my career with Def Poetry and moved on to all the producing and television stuff that I wanted to do, I probably would not be alive today because it doesn't change the way my brain works. It just changed the way that I, that I was moving through the world and I would have been a shell of a person and I would not have made it. The thing with Erica, like, one of the reasons I'm still here is because of Erica. Erica is the one who encouraged me to write openly about it in the way that made sense. She was like, “I can't do this, but you can do this for us.” You know what I mean? And this is the first conversation I had with this woman. Like the first conversation I had with this woman. I knew her name. Of course, you see her byline, you know, everywhere. And she just started talking to me and created this community for me that I'm so grateful for. But, knowing that Erica didn't make it, I felt almost responsible for Erica and her memory and all that she had given to so many people that she couldn't give to herself. Um, trying not to cry. It’s quite… Uh, there’s a young girl by the name of Siwe Monsanto. When she was 15 years old, took her life. We used to babysit her growing up. The Siwe Project, the foundation I started, is named in her honor, and I think about her as well. And I think about all that she couldn't accomplish because she was suffering in this way. And I feel responsible. I feel like I've got to try a little bit harder every day. I feel like it takes a little bit more work for me to get up in the morning sometimes, but I gotta get up. I gotta get up because I’ve got things to do and I've got a vantage point that makes it sometimes easier for me than it, than it was for other people.

Rebecca: Is there a difference that you feel between responsibility and then being a role model?

Bassey: Responsibility for me means that I am grateful for all the people who have saved me. I lucked out. I lucked out with those, my first doctors, I've lucked out with therapy, I've lucked out with medication, I've lucked out with a family that I have that's been very supportive and very diligent in helping me. Um, I lucked out. So, because I know there are people who have different situations, I want to be able to talk about it. I wrote the book the way that I did because I wanted someone to be able to hand it to someone else and say, “This is what it feels like.” So I have a responsibility in that because I'm always filled with that gratitude for all the luck that I've had. But I don't want people to think that the way that I am or the way that I did it is the way they need to do it. I want people to understand that there is a path for them that makes sense for them, and I want them to be able to just see it. Not see it because they're looking at me, but just see it because it exists for them.

Rebecca: You said earlier, “You're going to get me canceled.” What was it that you thought would get you canceled?

Bassey: I have a… You want me to say it?

Rebecca: Yeah.

Bassey: I have a, I have a, I have an issue with, with the way we celebrate black excellence. It's usually the five-year-old who graduated from college at, you know, who graduated from medical school by the time they were in the seventh grade or something. You know what I mean? Like, it's these huge things that it's just impossible for people to see themselves in. And it's great to celebrate as black people collectively, but on an individual level I think that the way that we talk about our magic and our excellence needs to shift a little bit. I think that CaShawn, um, Thompson who started the, the black girl magic hashtag in the Twitter iteration, because I'd heard it before, she meant it for everyday homegirls. Like, everyday round-the-way black people and it, it got away from her and it became about these huge, unattainable Beyonce levels of success that it's not realistic for me. It's not realistic for a lot of people I know. So what does that mean for me to tout black girl magic? Sometimes it means that I brushed my teeth twice. You know what I'm saying? Because there are times in the worst of my days when I would just lay in bed filthy for weeks because I did not feel like I deserved to have a clean body. You know? So when I take a shower, when I brush my teeth, when I get dressed, um, in something other than, you know, yoga pants, I feel magical because I remember what it was not to be that, not to want that, not to feel that. And I want it to be about these attainable successes and these attainable magical moments as opposed to these, these ways that are so huge and so excellent that we will never see them. We're never going to be Diddy and Jay-Z black excellence. So what does black excellence mean to you on an everyday basis?

Rebecca: So, shifting slightly, it's an election year and we're having conversations for this podcast that we consider essential. So what do you think the essential conversations for this year should be?

Bassey: The thing that comes to mind immediately is healthcare. I think that on a physical, a mental, emotional level, we all need access. I'm fortunate to live in Maryland that has an amazing state insurance. It's amazing. I can go anywhere and get the help that I need and not feel like I'm getting treated less than. And I think it's a fantastic model for the rest of the country, and it's heartbreaking to know that there are people who can't afford to get the help that they need on any level.

Rebecca: Inside of that, what do you think is the essential conversation for people to be having about mental health, specifically the mental health of black women?

Bassey: Um, so many people don’t have the access to the proper care. And I, and I want a, I want an actionable plan from people about how our communities are going to be serviced as far as our health. The fact that we have to go to a white or, or a more affluent neighborhood to get the proper medical care in an emergency situation… How are you going to widen access for all of us? But one of the conversations I've been having with people is I was blindsided in 2016. Like, I woke up and I was like, “What is happening?” And I’ve felt blindsided ever since.

Rebecca: How did that affect your, your healing, your, your mental health or your, your day in, day out, or how has it?

Bassey: Girl, I was depressed. 2016, I was, like I said, it was one of the worst depressive episodes I’ve had. And it made me feel hopeless. It made me, like, wonder why I was working so hard to be here if we're all going… It, it affected me in ways that I found shocking because I was never really that invested. I, I'm into politics in that I, I talk about it and there I'm a very liberal, progressive person in my, in my life. But I felt like this was a sign, especially surrounding all of the black men, black people being killed unjustly. I felt like, like we were going backwards, so I was very, very disappointed and I was very hurt by the fact that things weren't getting better the way that I'd always convinced myself they were. It made me very pessimistic in ways that aren't healthy for me.

Rebecca: Do you think about the legacy, though, of black survival and thriving in America and elsewhere? You know, despite multiple oppressions. I mean, in your darkest moment, have you taken inspiration from all of those who've come before us and survived?

Bassey: I think we are a remarkable people, and between, you know, enslaved people, colonized people, white supremacy and how it devastates, has devastated the continent, um, I appreciate it and I'm grateful for that, but I don't want suffering to be our legacy.

Bassey’s book is called I’m Telling the Truth, But I'm Lying and you can follow her on twitter at @BasseyWorld.

If you are experiencing suicidal feelings or know someone who is, please get help. You can reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 -- it’s open 24 hours a day.

Christina Djossa and Joanna Solotaroff produce the show, with editing by Anna Holmes and Jenny Lawton. The show was mixed by Jeremy Bloom. Our technical director is Joe Plourde, and the music is by Isaac Jones. Special thanks to Jennifer Sanchez.

I’m Rebecca Carroll - you can follow me on twitter @Rebel19. Thanks for listening. Until next time.