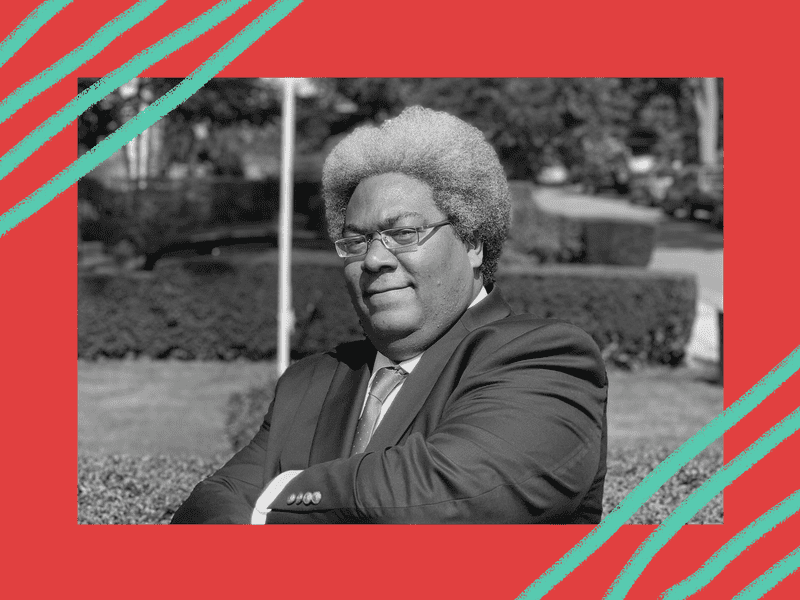

8. Elie Mystal: Call It a Lynching

( Courtesy photo. )

I grew up in rural New Hampshire, where everything and everyone was white, including my adoptive family. One summer when I was probably six or seven, an older girl who was a friend of my sister, tried to drown me. I’ll call this girl Kelly.

It was a sunny afternoon at Lake Winnepocket, where we spent many summer days when I was a kid. Kelly had offered to carry me out to the big rock in the middle of the lake. The big rock was set under the water a ways from the shore, and was a marker for where there was a sharp dip in the lake and where the water got super deep, and very dangerous. Most kids who swam at Winnepocket knew not to go past that rock, whether we could swim or not. I didn’t know how to swim. So when Kelly offered to carry me out to the big rock, it felt cool getting attention from an older girl.

She held me on her hip and walked with me out toward the rock. And then, when we got there, right where it got deep, she dropped me. The water closed over my head and my feet couldn’t touch the bottom.

My sister saw it all happen from about five feet away, where the water was still relatively shallow. She later said she was too stunned and that it happened too fast for her to do anything. But what she didn’t tell me until we were adults was that after Kelly dropped me in the water, as I gasped and flailed, she laughed at me and yelled the N-word at me.

But my sister wasn’t the only other person at the lake that day — there were probably about 15 other people, all white, and more than a few were adults. One of them pulled me out of the water. I still wonder, though, how many other people saw or watched it happen?

Kelly’s assumption that she could just dump me in the water and watch me sink while openly calling me a racist slur in front of over a dozen people without concern or consequence... It haunts me to this day. And I was reminded of this memory again recently, after reading about yet another murder of a black person caught on cellphone video, and that was circulating on social media: Ahmaud Arbery, 25 years old.

Right away black folks started referring to this as a lynching — a word that has especially poignant meaning for black Americans. Lynching was a terrorist tactic used by white people during slavery to remind black men, women and children where they belonged. They were hung from trees in front of crowds of white people as a form of entertainment — the spectacle of it was the point, the killing and its manner were almost secondary.

It was February 23rd, a Sunday afternoon, and Arbery was jogging in his neighborhood in suburban Georgia... when two white men, a father and son, got in their pickup truck, hunted him down and killed him without any justifiable reason. A white man in a nearby car caught the murder on video with his cellphone — he recently spoke in public for the first time, and said he was in shock, and that’s why he didn’t do anything to intervene. But it also seems that he held onto that video for months — the footage didn’t even surface until a couple weeks ago, nearly three months after Arbery was killed.

But what actually constitutes a lynching? If I had drowned that day in the lake in broad daylight, in front of a crowd of white people, would that have been a lynching? What sets apart the white adult who pulled me out of the water and the other white adults who may have seen me drowning but did nothing?

I believe that my sister was stunned by what she saw, but I also sometimes wonder if as an 11-year old white girl in America, something hadn’t already been ingrained in her mind, either through school or TV or who knows where, that betrayed her instinct to save me.

What is the broader moral responsibility of white people to understand what a lynching is? What is the professional responsibility of national media outlets to distinguish between a murder and a lynching? And what is the difference between a murder and a lynching?

To help me parse through some of these questions, I invited Elie Mystal to come through. Elie is a trained lawyer and commentator who recently wrote a piece for The Nation called, “We Didn’t Need Video to Know that Ahmaud Arbery Was Lynched.” And we got right into it.

Elie: So, because of my legal training, I tend to break it down this way. I'm not saying that my definition is going to work for everybody and I don't mean to, I don't have an agenda with this word. I use the word “lynching” when I am looking at an extra judicial killing, most importantly, right? So it's a killing that happens outside of the authority of the rule of law. It's vigilantism. And then what separates, like, a lynch mob from Batman is, is that the crime that the person is being killed for is their blackness, right? Like, that's, it's vigilantism against blackness as opposed to vigilantism against, you know, psychotic people in clown makeup. Right? In a way that’s more of a narrow definition than some people. We'll, we'll use it, uh, because I, I think it does require the racial component to make that word stick. But in a way, it's a more expansive definition than a lot of people use it. Because some people will use that word to describe, you know, every killing of a black person. And I won't, right? Like sometimes it's just murder.

Rebecca: When is it just murder?

Elie: Murder I think to me requires a little bit more of a personal component, right? Like you hate the black guy who also did something to you. Who also, you know, offended you in some way. Why you got offended might be its own racial, you know, pit of despair. But there's some kind of personal connection, um, to a murder. A lynching, you don't know the guy, you’ve never met him before or her before, you have no personal grievance against the person. You have a grievance based on the person's race. Right? To me, that's the turn of a lynching versus a murder.

Rebecca: So wait, would you say that lynching in our country is uniquely American?

Elie: Oh yeah. Yeah. I mean, I don't, I don't really care about how white Americans use to figure out how lynching isn't their fault. No, lynching is there. Like, they invented that term, that, um, crime. And they invented it pretty early on. Legally, I think it does go back to Lynch's law, a Virginian, who had some law that allowed for, again, these kind of extra judicial killings. Which is part of the reason why I center the word in that concept. It's a thing that was used against African Americans, to make an example of African Americans, who stepped outside the social bounds that whites had for them. Right? Like, that’s an important thing that we can't let pedantic history buffs allow us to lose sight of. Lynchings are done by white people to keep black people in line. It is a terror tactic, right? To make sure that black people understand. It might not have been used this time, but it could be you at any time so always be afraid and always be respectful and cower in front of white authority, real or perceived. Right? And that perception of authority is another aspect that I think is important when we're talking about lynchings. It's what the McMichaels used in this case. If you, for those who don't know, the older McMichaels is a former police officer. He was an investigator for the district attorney. It's one of the reasons why charges were so long in coming. Again, admitted in the police report that they kept shouting at Arbery, “Stop, we just want to talk to you. Stop, we just want to talk to you.” Again, the hubris of these people to think that they could be chasing after a black guy in a truck and have the authority just to stop and talk to him… Like it's just ridiculous. But that apparent authority is actually critical to a real conception of lynchings. What it comes from is the thought that white society writ large has the authority to police any black person that they find stepping out of line anywhere they might find them stepping out of line. That they don't need to go to the cops.They don't need to go to official authorities. Whites’ authority alone is enough to interdict an African American.

Rebecca: I think what I'm also trying to gauge here is when and how we use that word, “lynching,” both personally and professionally, but in particular when it comes to the media. Would you say that the decision of when to use the word “lynching,” is similar to when to use the word, say, “racist,” right? Like, a lot of media headlines did not use “lynching.”

Elie: Yeah. I mean, Rebecca, I mean, this gets into issues of white media that I don't know if I'm fully prepared to talk about. But like, there's such a desire in white media to write things in a way, or headline things in a way that will appease racist, right? Like white media is more concerned with appeasing the very worst people in our society. As opposed to A, accuracy or B, appeasing the people who actually read their stuff. It's frustrating and amazing at the same time. I was watching Chuck Todd talk about this story. And he said before he showed the video, “Now, you know, we don't know what happened before this video was recorded.” Man, go jump in a lake, Chuck Todd. What could have happened before that video started shooting to justify the crime that was shown on the video? That little tic, and it was a two second thing… You had to get, your antenna had to be up to even notice. It was a two second thing, but that two second thing, that microaggression by Chuck Todd against the life of Ahmaud Arbery is, is what bothers me more than whether or not they use the word “lynching.”

Rebecca: But what is in Chuck Todd’s mind when he says that?

Elie: Right? I don't mean that, I don't know. Like, who was he trying to please? What master was he trying to please by saying, “We don’t know what happened before this video…” Like, and that's the thing. He wasn't trying to please anybody. It's just a tic. It's just how they've been trained to think and process the death of black people. Right? That, well, there's always the possibility that they deserved it. It's just an internal tic. We never know if the black guy we see being mercilessly destroyed on camera... We don't know if he deserved it, so let's leave open the possibility that he did.

Rebecca: I get so frustrated, which is an understatement, though, by this whole notion of white people being trained. You know, that it's so ingrained that they can't find their moral center. Like, I just, at what point do white people find their moral center? Like, what has to happen?

Elie: Um, I, I don't know what it takes. I don't know what it takes. I don't know what more they have to see or hear or witness. The only thing that I do know is that I think affirmative action helps. I think that one of the things we've seen over the course of history is that the more white people are forced to meet non-white people, the more they are forced to interact with non-white people. Um, the more they get to know us, the better they are. And more importantly, the better their children are. Like, Chris Rock has this great joke, right? That, you know, what needs to happen is that America just needs to start producing some better white people. And that's true. And to me, the way that we get there, the way that we have gotten to this point, um, and the way that we will continue progressing is through programs like affirmative action programs. You know, integration programs when white children have to interact with non-white children, with black children, children of color. When they get to know them, when they become friends with them, they're less racist when they grow up.

Rebecca: What do you think it means, though, that the video resurfaced and circulated and broke through the news cycle during a global pandemic that is disproportionately killing black and brown folks?

Elie: Why did it break through the news cycle? I think sometimes when you hold a mirror up to white people and show them what they do, show them who they are, they are horrified. If white people saw themselves as I see them, as many black people see them, they would be horrified at the view of themselves of how they look to non-whites on a regular basis.

Rebecca: You think so? You really think so?

Elie: I think most white people would be horrified to see their world through my eyes. The reality of our world is that the average white person could not handle living as the average black person in this country for a damn week, right?

Rebecca: Right. And so when you say the average white American would be horrified to see themselves the way you see them… What do you see when you look at white people?

Elie: Extremely privileged bunch of brothers who walk around this world like they own the damn place. Right? They walk around this country and this world like they own the damn place. Like everything exists for them. Like they are the stars of their own sitcom and that everybody else has to fall in line. Right? And that fundamentally is the crime of blackness in this country. It's the crime of reminding white people that they don't in fact own the place. That they don't in fact own us anymore, that they don't in fact own women anymore. Black people remind them that they do not walk around owning people anymore.

Rebecca: And we remind them of that just by existing, right?

Elie: Just by existing, just by walking free, just by opening our mouth, just by having jobs. And some of them react quite violently to that reality.

Rebecca: And so this is what happened to Ahmaud Arbery, right? In your mind, two white men decided on, like a dime, really, like, “This guy is black. There have been some crimes. We have guns. Let's go get him.”

Elie: “Let's go do something about it.” Right? They knew that they could, right? That's, that's the thing that gets me about this case, um, more than some of the other ones we've seen. The presumption that they could hop in their truck, get guns, go hunt this man down, fully expecting not only to get away with it without reprisal, but to be potentially lauded for their efforts in crime fighting, right? It is so far removed from the experience of African Americans in this country. The way that I put it in my piece was — can you imagine what it would sound like if we flipped the races, right? Can you imagine if I was sitting in it outside of my home, you know, watering my garden and some white person jogged past my house? What kind of person would I have to be to feel like I have the right to hop in my car with firearms and go pursue that person because he fits the description of, I don't know, every mass shooting that I've ever seen. Because he fit the description of, I don't know, every bank embezzler I've ever seen. Right? I then had the right to go apprehend… Like, what does that take? It takes whiteness is what it takes. That is the indispensable ingredient in their crime. It's whiteness because if you don't have whiteness, you don't even think that you have the right to do that.

Rebecca: Right. I mean, I think that is an interesting question. And I think really the only question left after whiteness is, what kind of person do you have to be? Like, that's what really sticks in my craw, so to speak. You know, like I have dealt with white people my whole life. I know what they are capable of, but to think that this life is so absolutely valueless. I mean, it's not even like they were on drugs… Like, I just, I can't wrap my head around that. Like, past whiteness, past white privilege, past white supremacy, Is there a lack of moral existence?

Elie: That’s, to me, that's what distinguishes these white people from every white person, right? Like, whiteness is necessary but not sufficient to commit violent acts of racism, right? But the sufficient component also requires just a psychopathic, almost, disregard for human life that not all white people… Like you're not born with that. You're not raised with that. Like you have to, that's the special sauce that turns, kind of, I don't want to say benign racism because racism is never benign. But that's what turns kind of nonviolent racism into a lynching, into a killing, into getting a posse of your friends to go out and hunt some black people. That takes an extra level of oomph that these people clearly had.

That’s Elie Mystal. Coming up, do you share the video or not? That’s in a minute.

Rebecca: I want to go back just a minute to, um, to the lynching and sort of when to use it, when not to use it. Who gets to say it? Does the definition of it, or the meaning of it, rather, change depending upon who says it? Like, does it matter to you if a white person uses the term lynching?

Elie: Uh, well, number one, because of my job and my profession, I tend to be, like, very, like, pro First Amendment. And that also leads me into this, like, negative language police thing where, like, if you're gonna be white and say it, I'm not going to be the guy to stop you. I'm also not going to be the guy to listen to you. Right? So.

Rebecca: So do you think that in this particular case, white people should use the word.

Elie: It was a lynching.

Rebecca: Right, yeah.

Elie: So they can use that word accurately in this case, or not, as they determined. But it was what it was. White people saying that it was, doesn't change it. Right? It doesn't make it more or less of the thing that it is just because a white person in authority calls it the thing that it was.

Rebecca: But there is a responsibility, no? To be accurate?

Elie: Yes. But, that goes back to my media comment, right? Like, I believe that the most accurate way of describing this particular crime is: Lynching. I think the other thing that's worth kind of exploring with this space is does the use of the word lynching change how white people view the crime?

Rebecca: Right, exactly.

Elie: I am of the belief that black people are going to view that crime appropriately because it is exactly the kind of crime that many black people, especially African American parents, are terrified of. Like this, as a parent of black boys, this is the crime that hits me where I live. This is the crime that makes me lose sleep at night. I think there are a lot of African American parents who are going to feel the same way that I do. Calling it a lynching, does it make white people more aware of what happened and why people are so outraged about it? Um, I think so. And so that's why I think the word should be used. I think it does heighten the, the reality for white people. It makes them more likely to appreciate the horror of this crime appropriately. But by the same token, if you think of this incident as individualized, then you missed the whole point. The word lynching is used to show that it's not an individualized crime. It's a crime that happened to one individual. It's a crime that was perpetrated by two individuals, but this is not an individualized incident and lynching should help people see that. But if you can't see that, then you've missed the whole point of this discussion. You've missed the whole point of why this particular episode is making the news.

Rebecca: I think one of the things too, for me, that I come up against with white people specifically and their understanding of lynching, is how central the spectacle aspect of it is that the killing is kind of secondary and that the primary attention is to watch a black person die. Do you think that Arbery's lynching counts as spectacle because it was captured on a cellphone or because it was captured on a cellphone and then shared on social media?

Elie: Yeah. I mean, this is where we get into the, the knottier question of whether or not the video should be shared at all.

Rebecca: Right.

Elie: Key to lynching. Key, is the public spectacle. Again, it doesn't work as a tactic unless you are disseminating that tactic to other black people, not yet killed. So there's a reason why lynchings always make the papers, right? These are, these are white papers, right? Um, controlled by a white racist. There's a reason why they would highlight lynchings in their pages. Um, that's why black people who were hanged were left hanging. Right? That's why they didn't try to hide the evidence. Uh, and I think with, um, Arbery, um, what you see with the video is a little bit of that memorialization of the crime. That the video itself is a warning. So with that said, do we essentially do their work by sharing, disseminating, and talking about, um, this traumatizing video. I think it's a really difficult question and I kind of go back and forth. I think that the video was unnecessary for the prosecution of the crime. You didn't need the video to know that a crime had been committed because the perpetrators of the crime admitted their crime to the police officer on the scene. The video therefore only serves to popularize the crime. However, it is undeniable that these white prosecutors in Georgia would not have acted without the public dissemination of the video. I think one of the things that was going around last week on social media… They did not charge the McMichaels because they saw the video. They charged the McMichaels because we saw the video. Right? The video is what spurred the justice system to take any action at all against these people. Who knows if they'll actually be convicted. They found a black woman who happens to be a Republican, appointed by Governor Kemp, who stole the election from Stacey Abrams. That's who they found to prosecute this case. So we don't know if that's going to go well. So we don't know if the video will actually lead to conviction, but we know that the video led to charges.

Rebecca: You wrote in your piece, “Um, why do we have to wait until the entire black community can be traumatized by video evidence of a lynching before some white people are moved to act?” Um, and we are talking sort of here about sharing the video and, you know, a lot of black folks have shared it. You know, it's split, right? I would say right down the middle of sharing it or not to share it. But I'm wondering if there's something about our trauma that compels us to share the footage.

Elie: Look, it's real. All right. Because every black person up in here has been in the situation where some racist thing has gone down, has been perpetrated against them, and they have told white people about it and white people said, “Nah, that ain't racist. He didn't mean it racistly. You're wrong. You're lying. You're making it up. You're exaggerating.” We've all heard it, right? We've all been forced to prove our pain to white people at some point in our lives. A video like this is part of that proof, right? I'm not making it up. It's not in our heads. It's not that black people are obsessed with slavery. It is happening today in 2020 right in front of your eyes. Look at this video that proves it. Because of our experience in this country, because of our experience with white people in this country, there is a need to prove that what we say happens to us actually happens to us. And this video is evidence. This video is proof. And part of, at least a lot of the black people that I've seen share it… Part of the reason why they're sharing it is to establish that proof. You know, a lot of times when I’ve seen it shared it's with the tagline, “Look at what happens to us. Look at what they do. Look at how they be.” Right? Like, that is part of why this video is being shared. Part of the reason why I haven't been psyched or, or, or quick to share the video myself, is that I try to live, I like to call it, I try to be a fully emancipated black man. And part of that emancipation process, which is still a process for me… It's still something that I struggle with, but part of that emancipation process is to not need white people to believe what I say, to not care whether or not white people believe me or not. And not have white approval be important to my life in any way. And in that vein, I don't need to share the video to make some white person understand that my pain is real because I don't need to care whether that white person understands that.

Rebecca: Is there also, though, not the fear of normalizing the violence?

Elie: I mean, I don't fear that as much as other people because I feel like the violence against us is already normalized.

Rebecca: Right.

Elie: I feel like they've already won that battle because it's not like this is the first, this is not the first video. This is not the first example. White people already know the kind of violence they commit against our bodies, and they're already okay with that. That's already part of the deal. And so I don't think that there's any video that can accelerate that process.

Rebecca: Again, I mean, I feel like it's about having a moral compass. It's about having a sense of, just, humanity. It's bizarre and I'm glad that it's still bizarre and that I don't feel to the point of complete cynicism. But it's bizarre to me that anybody would look at this video, of this man literally being gunned down in broad daylight for jogging and being black, and not be absolutely horrified to their core.

Elie: I mean, I think many people are, just not the people who did the shooting or prosecuted the crime. Right? Like, it's that, and I think this is, this maybe is a little bit too in the weeds, but it is something that I think about sometimes in terms of white people versus white people in a position of authority. It's easy enough to be white and be horrified at things when there ain't nothing you can do about it. Right? It's easy enough to be black and be harmed by the things when there ain't nothing you can do about it. But when you're white and in a position where you can do something about it, for whatever reason, that seems to make white people less willing and able to do something about it. Um, and so, yeah, I can imagine that lots of white people who don't, can't do anything, saw the video and were shocked. But the white people who could, the first prosecutor, the second prosecutor who wrote an entire letter defending the killers, the third prosecutor who sat on the video for a month, the governor, Brian, all of those white people, those are the white people we needed to be horrified. And they weren’t sufficiently.

Rebecca: I was really struck by what you said toward the end of your piece that, you know, you don't know why. You don't know why white folks are titillated by the snuff films of murdered blacks before some of them are willing to consider the notion of justice. That word “titillating.” Just, ran, you know, chills. Um, why did you use that word?

Elie: Because there's an excitement here. You see it in some of the people who are sharing it. There's a fascination. There's a morbid curiosity with watching a person die. That sure, that they can then turn or reformat into outrage and demands for justice and all that stuff. But at a core level, there's something base and gritty and nasty, um, about watching a life taken from a person and then having that kind of be the motivation for political point. There's a seediness to it. That's why I use that word.

Rebecca: But it's specific, I think, to white people watching black death. Do you think, or no?

Elie: I think so. I have difficulty proving it because there aren't a lot of films of white people getting shot, now, are there?

Rebecca: No.

Elie: There are a lot of movies where it happens. A lot of war films where it happens. So I don't know if white people would react the same or differently if it was somebody who looked like them who was being murdered by police. I know that they would react with the same level of fascination if the killing was done by a black person. Like, there's an exoticization of violence against black people, but there's also an exoticization of violence committed by black people. Right? Um, white people seem to find both of those aspects as intriguing as the other. Um, I'm sure if there was a video of a black person beating the snot out of a white person, those would go around all of right-wing media and you’d see them on Breitbart and they’d go, you know… Republicans enjoy sharing those videos especially amongst themselves because it justifies their, they think that that justifies their entire regime of white supremacy. But if it was white on white violence where it was just Gregory and Travis McMichael shooting a white jogger to death, I don't know how much they would be sharing. I don't know how they would be reacting to that and I can't take the Pepsi challenge with it because that video doesn't really exist.

Rebecca: Right, right. I think, of course, about the historic moment in America when Justice Clarence Thomas in hearings, you know, that claimed he had sexually harassed Anita Hill, called the case a high-tech lynching. Do you remember what you thought about it then when you heard him say that?

Elie: I was aware of that confirmation hearing. But I wasn't even in high school yet, so I didn't have the full historical understanding of how ridiculous it was for him to use that word. When I kind of learned about it later, what struck me was how Thomas will always use the specter of racism against himself to justify the racism that he is permitting to exist or actively engaging in, towards other people. It's a very depth thing that Thomas has done for his entire career. Now with the understanding of what his career has looked like, I now understand that moment to be his first real experience with just how useful his little trick is, right? He was able to distract from his own terrible, and uncontroverted by the way, sexual harassment of Anita Hill by throwing white people off the scent by using this word. It was, I don’t want to say brilliant because I don’t think evil genius is particularly brilliant, but it’s evil genius. Right? It’s his whole shtick, it turns out, is exactly that this use of the specter of racism to justify his racism.

Rebecca: Can you imagine hearing a high-profile black man in his position or, or any high-profile position, using that term today?

Elie: No, but I can imagine white people doing it, right? Like the analogy of being held accountable publicly for something that you did, or allegedly did, to being hunted down by a mob of vigilantes and strung up from a tree. That's the analogy that Republicans are now comfortable making, and you don't even have to be black to make it if you're on the Republican side anymore. That's where that party is. I cannot imagine a high-ranking African American Democrat using that term. But I can imagine, like, low-ranking Democrats using that term, less national profile Democrats using that term, because one of the things that we've seen during ‘Me Too’ is this feeling from men that, again, being held accountable for their past actions is somehow wrong.

Rebecca: Right. That's what I was sort of getting at earlier about who uses the word, how it changes, who gets to decide. And it sort of tends to always come back to white men somehow.

Elie: For all the white men who complain about political correctness and the language police and the pronoun police… White men invented the language and they still do. White men invent the language, control the language, try to use language to oppress other peoples. That's all an invention of white people in this society. Our language is completely tied to their viewpoint and they get pissed off when we say they not shit. It's just, it’s hard to swing out from under all the layers of hypocrisy that go into the white man’s annoyance at having to use appropriate terms when they invent all the fricking terms.

Rebecca: So if you could see some kind of change about the way in which these sorts of stories are told, what would it look like?

Elie: There would be African American people in the damn newsroom. We've been talking about hubris a little bit. Part of the hubris from white media is their thought that only white people need to be involved in the production of media. How on earth are they running stories about the killings of black people without having black people on staff, black people in the production meeting, black people on the editorial board just giving a different point of view? You think that would be kind of crucial for stories like this. That would be the change.

Rebecca: Fair. Elie, thank you so much.

Elie: Thank you so much for having me.

That’s Elie Mystal - you can read more of his work at The Nation and follow him on twitter @ElieNYC.

Christina Djossa and Joanna Solotaroff produce the show, with editing by Anna Holmes and Jenny Lawton. Our technical director is Joe Plourde, and the music is by Isaac Jones. Special thanks to Jennifer Sanchez.

I’m Rebecca Carroll - follow me on twitter at @Rebel19 for all things Come Through.

Until next time.