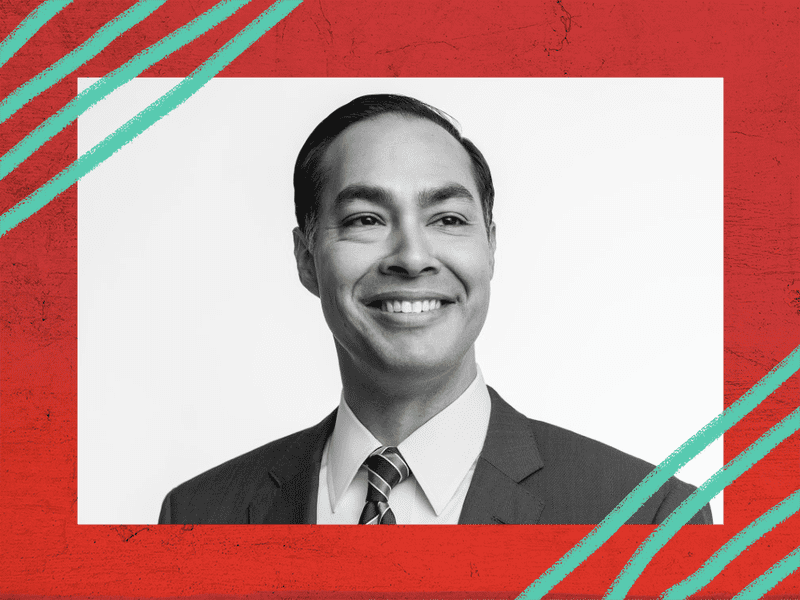

15. Julián Castro's Common Census

I’m Rebecca Carroll and this is Come Through: 15 essential conversations about race in a pivotal year for America.

It’s been almost four months since we launched this podcast — four months that have felt like decades, not least of all because we’ve been under quarantine. But also because it feels like for the first time in actual decades, and certainly in my lifetime, white America appears to be experiencing what’s being considered a racial reckoning. And we’re watching this national conversation around anti-Black racism evolve in real time.

During the Civil Rights era, protests led to legislation that forced white people to treat Black folks as equal — and while the laws were in place, they didn’t necessarily take. But the protests and uprisings sparked by the police killing of George Floyd this past spring have prompted a semi-implosion of white supremacist infrastructures in pop culture, and the publishing, retail and museum industries.

Powerful white men have resigned from high-ranking positions — I mean, not enough, but it’s a start — historical statues have been torn down, corporate heads have issued public letters of apology, white actors have given up animated voice-over roles, Taylor Swift is tweeting about the perils of white supremacy. Several states have decided to declare Juneteenth a holiday. And the book “White Fragility” by Robin DiAngelo, has been on the New York Times bestsellers list for weeks. (By the way, you can hear Robin DiAngelo on this podcast — listen back to episode 5.)

It’s a little surreal, though, because how do we, as in Black folks, reckon with the racial reckoning of white people? It can be tricky and frustrating and just straight up wild to try to process and trust what we’re seeing and hearing. For me, it’s a constant negotiation between working for big picture, systemic reform and maintaining my personal sanity.

I spend a lot of time writing and thinking and talking about race and racism in an effort to create broader cultural and social change — which involves interrogating a lot of whiteness — but it’s in the moments with the Black family I made, and the Black family I chose, that I feel the most powerful and hopeful about being Black in America. Because we live in conversation and community with each other.

Yet, when I step outside of that feeling of strength, being Black in America becomes a very different experience.

2020 is an election year. It’s also a census year, when the government asks us all to stand up and be counted. And whenever I have to check a box that identifies me as Black to our government, I feel a mixture of skepticism and rage. Skepticism, because there’s no guarantee of what the government is going to do with the information of my Blackness. And rage, because there should be. I should be able to check that box and know in my gut that giving over this information will improve my life and those of others who look like me.

Which is why I wanted to talk with Julián Castro. He served as the mayor of San Antonio, Texas before joining the Obama administration as Housing Secretary. And he was briefly in the race for President, as the only Latinx candidate in the 2020 Democratic primary. Since then, he’s been super vocal about the importance of filling out the 2020 Census. And I wanted him to explain to me why.

That’s first up on today’s show… which is also the final show of the season. And, as I said, at this moment, I find myself moving between the political and the personal. So we’ll end this episode with the first voice you heard in the series, and the voice that helps guide my day-to-day, my dear friend, Caryn Rivers.

But before Caryn, here’s my conversation with Julián Castro. I started out by asking him pretty directly, “Why is it important for me to fill out the Census?”

Julián: The census is the best tool that we have to make sure that our communities, that your family, your neighborhood, your local community, uh, has the resources that it needs to prosper economically, to be healthy. The census is the number one way that resources are determined for communities across this country, from how much investment your child's school is going to get to whether that road that you've been complaining about that needs to be expanded is going to get the attention it deserves. All of those things are profoundly impacted by whether you're willing to stand up and be counted by filling out that census form.

Rebecca: I mean, as you certainly must know, there's a real mistrust among Black and Brown folks about handing information over to the government. What do you say to those folks?

Julián: I understand the skepticism. Uh, I know why people would be concerned, especially with the president that we have right now that constantly is trying to instill fear in communities of color about what the government might do, could do, and, in some instances, has done to target them. However, people should know that it is against the law for anyone to use that census information for anything other than the purpose of counting the people who are in this country and being able to make decisions about investing resources. They can't take that information and turn it over to immigration. They can't take that information and somehow go after you in any other way. It's against the law to do that. And my hope is that listeners out there will, you know, themselves and then also to their families and their friends, they'll convey that message. You know? I know that it takes a little bit of a leap of faith during this Trump era, especially, but that is what the law says and that's how the law will be enforced.

Rebecca: Because he thinks he’s the law.

Julián: Yeah. He thinks he's above the law, that it does not apply to him, but it does.

Rebecca: So how do you keep your level of concern in check? Are there tangible ways that you can tell people that census information is beneficial and works?

Julián: Absolutely. I saw this firsthand when I was Secretary of Housing and Urban Development for President Obama. The number one way that a lot of these programs were decided, in terms of how many dollars were going to go into a community to address homelessness or to fix housing stock or to help fix roads, that was through those numbers in the census. So I saw that it can make a difference in lifting up the prospects of everyday Americans out there, and there are no communities that need it more than Black and Brown communities that are already suffering in so many different ways.

Rebecca: One of the sticking points I think of the census is that you look at it and it can bring up a lot of questions about identity and race, right? And how we categorize race, especially. Um, I think Southwest Asian, Middle Eastern and North African people all have to check off that they're white, which obviously feels like erasure to a lot of folks. What do you think needs to change about the way that the census and, sort of more broadly, government institutions approach questions of race and identity?

Julián: Absolutely. I mean, you know, it's been a process of the US Census Bureau getting more and more thoughtful and more equitable and more inclusive over the years. There was a time when the Census Bureau was not as interested in a breakdown of the Latinx community or the African American community as it is today. When I was HUD secretary, we were working to get a better count of the LGBTQ community into the census. In each and every one of those ways, there's still progress to be made. We want to meet people where they are and we want to allow them to express in the census who they are so that we can get an accurate count out there that reflects the identity, as beautiful as it is, of this entire country.

Rebecca: You know, an argument that comes up frequently, and seems to be in my Twitter especially often these days, is how people try to categorize Hispanic people and the argument that Latino isn’t a race. What's your take on that?

Julián: Yeah, I mean, you know, and, and within that Latino community, of course, over the years, there's been a lot of back and forth about how people identify. Even just take, you know, my example of somebody who's of Mexican heritage, right? Some people prefer Hispanics, some people prefer Mexican Americans, some people prefer Latino, Latinx, Chicano. I think that what makes sense though is to allow people to bring that forward themselves, to give them the option for their identity to be reflected in the choices that they see on those forms. And so, you know, I've tried over the years not to really enmesh myself in all of that back and forth and to say, “Look, you know, however, people want to identify themselves, they should be able to.” But what I do support, absolutely, is that they have the option of doing that on those forms

Rebecca: I mean it’s really fraught though, right? And why do you think that is?

Julián: I think that any time we address these issues, like there's going to be a certain crowd that just wants the status quo and you know, feels somehow… I don't know if they feel that they're a step above because there is that category and for others there's not. Or somehow feels that they're going to be bad consequences if you recognize, I don't know. You know, and, and frankly, I would be lying to you if I said that I spent too much time going and tying different arguments that people make over it, except to say that it's very clear the community is a major presence in this country. I think it was 1990 there was a book that was written called “The Disuniting of America” by Arthur Schlesinger. And one of the questions that he put forward was basically, “What would the growth of communities, like the Latino community, mean? You know, what would the diversification of this country mean? Would it mean the balkanization of America or would it mean that we're able to come together and create a nation that continues to get stronger and you know, it has some notions of the melting pot that I would think people have taken issue with and I would take some issue with?” But I think what we've seen over the generations is that it's a community, whatever you want to call the Latinx community, it's a community of people that have been hardworking, people that have been faithful to the country, whether they were documented or undocumented. They've been good community residents. Right now during this coronavirus experience, they’re a lot of the frontline workers, meat packing workers, farm workers, fast food workers who have often been on those front lines, but also get low pay and benefits. So my hope is that as we continue to diversify as a country, that more and more Americans will understand that what that diversification means for America is that we're going to have the same values, you know, of hard work, of belief in country, of family, of wanting to participate in a democratic process, that have been the underpinnings of a strong nation so far.

Rebecca: You know, obviously hope springs eternal. But I wonder how you're feeling about the election this fall, and if you think we've got any shot at a fair and just election.

Julián: Well, I mean, I would still rather be in the United States. If we were just saying, “Look where would you want to go to try and have, you know, as fair an election as possible?” The United States is still one of the countries that we would rather be in. However, I do have some very strong concerns about our election in 2020. We know that Russia is still trying to mess with our elections. Our federal government, specifically this administration, has never taken that seriously. At the county level, at the statewide level, where votes are actually tabulated, where voting machines are operated and administered, they don't have uniform election security. Oftentimes they have old equipment. They have been shown to be susceptible to hacking. So there are serious concerns and big improvements that we still need to make in our country. I also believe that the restrictions in place, because of this coronavirus, are going to create a dynamic for voting that is unlike anything that we've ever seen. We've had two examples now in the last two months of this. One of them was an election for a Supreme Court judicial post in Wisconsin, and the other was a special election in California's 25th congressional district. It concerns me that it seems like in that congressional district election, which as I understand it was mostly mail-in balloting, that a lot of the constituencies that are often the most vulnerable and often have, unfortunately, the track record of voting at a lesser rate, young people, communities of color, that they came out at noticeably lower percentages when we didn't have the opportunity for the same robust in-person voting. So what is that going to mean for November when our medical experts tell us that we may have another surge in the coronavirus, and if there are social distancing orders in place? If our voting now, I mean the mechanics, the physical mechanics of how we vote is impacted, people are not able, volunteers are not going to be able to, or block walkers go door to door and canvas neighborhoods in the same way. ‘Cause we know that, you know, these communities are, they require more effort to go pull out to get them to come and vote. And there's less in-person voting that's available.T hat really concerns me because I…

Rebecca: Yeah that doesn’t sound very hopeful.

Julián: Yeah, it doesn’t. My hope, yeah, I’ll bring it back to hope. My hope, though, is look, all of are going through this, I think, profound and, I think, both positively and negatively life-altering experience for this country. And my hope is that we're going to take an extra resolve out of all of this to make our country better, to do what we should be doing, to vote in the people that are actually going to make sure that everybody has healthcare in this country, make sure that every kid has that internet access at home that they need so that they can continue to learn, make sure that in the wealthiest nation on earth, that there aren't people that are still sleeping on the street tonight, and get rid of this notion that smaller, weaker government is always better and replace it with the idea that you need effective, competent government that is robust enough to provide broader prosperity in our country.

Rebecca: I do want to ask you, what is the appeal, the actual appeal, of running for president of the United States?

Julián: That's a good question. You know, I don't know that anybody's ever asked it quite that, that straightforwardly. Um, I, for me, it was that I got into politics because I have always felt very fortunate, very blessed, with the opportunity that I had in life to grow up in a single parent household, to go to these school districts where the odds would tell you that, you know, you ain't gonna probably ain't going to end up going to Stanford and Harvard law school, but my brother, Joaquin and I both had the opportunity to do that and then to get into public service. So I feel like I've reached my American dream and I got into politics because I wanted to work hard to make sure that everybody else could too. That's fundamentally what has animated my involvement in politics the whole way through, when I ran for city council, when I ran for mayor, when I served president Obama as housing secretary. And when I decided to run for president, I believed that I could lead this country so that we could have broad opportunity in a country that is stronger, uh, that we could all be proud of.

Rebecca: You all must have had family meetings. I mean, maybe not with your kids, but you know, with your wife, your, your partner, about how different it would be as a family if you were the president of the United States.

Julián: Oh yeah, no doubt.

Rebecca: How that must feel now that you’re spending time with your kids when you may have become president and not had this time at all.

Julián: No doubt. You know, no doubt. Um, I am very, very thankful that I'm having this time with my kids. I mean, people tell you before you have kids to enjoy it because they grow up so fast. And I never really understood what that I would, I would think when people told me that, “Oh, come on, what do you mean? It goes so fast? Like you're living your life like day to day. Like it would feel the same way.” It really does feel different with kids and you start to realize that you can't replace, you can't get those moments back, and that it's not the same when they're four as when they're thirteen or eighteen. You know, all of those times have, you know, there are positives and negatives, but there's something special about each and every time period in their life. And so, you know, yeah, I'm absolutely happy that I've had these last two months with them.

Rebecca: So the debates, like on the heels of asking about the appeal of, uh, running for president, I mean, the debates are hardcore and intense. Do you ever rewatch them or did you rewatch them?

Julián: You know, I did rewatch clips when we were getting ready for another debate. I haven't watched anything since after the last one that I was in, the fourth one, I think in October. But yeah, I mean those things are something else. You know? As somebody in politics and when you get ready to run for president, you think, “Oh wow, the debate stage, how's that going to be? Am I going to be nervous? Uh, you know, am I going to say the right thing or how's it going to go?” And what I found was that the preparation was just super helpful. And the teams of the people that are working on it, producing it from the networks, whether it's ABC or MSNBC, so forth, they're all professionals and they're really good at walking you through. And for me, that got me comfortable with those debates.

Rebecca: Were you nervous?

Julián: Oh, of course. Yeah. It was a little bit nervous, but what I found was that probably, you know, four or five minutes in, once you get into it, and especially after you get the first question, that those nerves kind of go away. It needs, I could understand then at that time, what sports players would say when they said they're nervous at the beginning of a basketball game or a boxing match or a football game.

Rebecca: I mean, it's a little, it's a little bit different when, you know, from a boxing match, when the long-term goal is to run the country.

Julián: It's true, you know? But I did have a fascinating conversation once with President Obama about his keynote speech and my keynote speech about nerves. You know, he gave the keynote speech at the DNC in ‘04 and I gave the keynote speech in 2012 and he said that when he looks at himself on tape, that he could tell that in the first, like, two minutes, that he was nervous. And I told him that for the first 30 seconds, like 30 seconds in, I thought I was going to pass out on stage in front of, you know, 25 million people watching. And you can almost tell if you look at it very closely, but thankfully, uh, I didn't, and I always tell myself that, “You're going to be fine. You can get through that. You can get through these debates or whatever else.” Yeah. That's my advice for people. Just getting into it is, uh, be prepared and you know, and be prepared for the nerves at the beginning, but then it'll be fine.

Rebecca: And what's next for you, provided we all can come out into the world again?

Julián: Uh, I'm going to keep using my voice to do everything that I can to move our country in the right direction. Uh, I'm going to be helping elect young progressives throughout the country in 2020. And we'll make an announcement about the vehicle to do that soon. I'm going to do what I can to ensure that we defeat Donald Trump in November. So, you know, I'm going to stay busy and, um, I'll always find a way, no matter what I'm doing, whether it's in the public sector or in the private sector, to make sure that other people have the kind of opportunity that I've had in life.

Rebecca: Just one last sort of, um, shallow question, what kind trashy indulgences are helping you through? Like, what trash indulgence is helping you get through right now?

Julián: Uh, I mean, I'm watching some TV. You know, I hardly watch any, any like regular sitcoms or stuff, but like AMC was having a “Rocky” marathon. I watched like the Rocky’s. My brother and I love horror movies, so I watched, like, several of the “Halloween” movies. I like boxing. So I’ll often be on YouTube watching old boxing matches, stuff like that.

Rebecca: You're a horror movie guy.

Julián: Yeah, yeah. They don't make horror movies the way that they used to, I think. But my brother and I grew up watching all of the “Friday the 13th,” “Halloween,” “Nightmare on Elm Street,” all those things.

Rebecca: Well, Secretary Castro, you are a delight, a lovely guest. It's such a pleasure to talk with you.

Julián: Thanks a lot, Rebecca.

That was Julián Castro — he’s @juliancastro on Twitter.

And there’s still time to participate in the census. The Census Bureau has extended its deadline to October 31, 2020 for online, phone and mailed-in self responses. For more information you can go to 2020Census.gov.

We’re going to take a quick break and when we come back, my friend Caryn Rivers.

I’m Rebecca Carroll and this is Come Through.

This podcast launched on April 7 — a day I’d been looking forward to because it was the day me, my husband and son were supposed to leave for our annual vacation with my friend Caryn Rivers and her son Anwar.

Caryn and I have known each other for a very long time. We moved to New York together in our early twenties and shared our first home in Brooklyn. Over the years, we’ve helped each other through tons of difficult turning points in life and relationships and jobs. We’ve watched the world change around us, and really just grown into ourselves together. We had our sons a year apart, and they’re both now in their teens. We are family.

Of course, we didn’t go on that vacation back in April. But we talked about what was going on — it was the start of something we knew was going to be big… but we didn’t know how big.

A lot has changed since then.

Rebecca: Hey, girl.

Caryn: Hi.

Rebecca: Um, so here we are. I started this podcast with a conversation between you and me, on purpose. It was at the onset of the pandemic and…

Caryn: Like, literally. Like, a week in.

Rebecca: And the podcast actually launched on the day we were supposed to leave for one of our annual trips together.

Caryn: I know, I know.

Rebecca: Is this the longest, I was trying to remember, that we've gone without seeing each other in person?

Caryn: You know, I thought about that. We haven't seen each other since Thanksgiving. So, that is eight months. It’s been about eight months.

Rebecca: That’s bananas. I mean, we did do, like, a little bit of the FaceTime thing, which doesn't feel like even… I don’t know. Did you warm to the FaceTime?

Caryn: I love the FaceTime.

Rebecca: Oh, you do?

Caryn: I love it all. I’ll take it all. I'm going to take my people however I can get them. You know? I love it all.

Rebecca: I also wanted to say, for you, um, and our listeners too, that the reason that I wanted to launch the podcast with a conversation with you is because our friendship really exemplifies to me what it means to come through, right? That notion of ease within Black community and Black family. And, unlike you, I don't have extended Black family. You and Anwar and Kofi are my Black family. And I just, I just wonder, does that feel like carrying a lot for you?

Caryn: Um, it feels like carrying a lot of responsibility, but right in keeping with what I've ever been told, taught, like, that's just what you do for family, because we're kind of a small family. Um, my branch, right? Like, my parents left their town and came to Philadelphia. So I'm kind of happy to have an opportunity to grow this branch, this new branch of the family. Right? And fold you into the rest of the branches, which, you know, goes hand in hand with holiday season. And then really, like, thinking about that, I just feel responsible because you know, the way I see it, your Black family is missing.

Rebecca: Yeah.

Caryn: And I feel like an unexplainable thing happened and your family is missing. And so, you know, it's just a responsibility. It doesn't feel like a drag. It just feels like I got to do that because something terrible has happened. And that's the thing. That's why I kind of compare it to that, the notion of missing persons. It's like there's an unexplainable piece to this, which we may never know, but there's no way that that family wants to be missing, but that's just where they are so we’ll build. Right?

Rebecca: We have built. And the other day, I mean, I think I told you that Kofi, um, was feeling kind of a way, like, about his Blackness and, you know, we had a conversation and I can only tell him what I can tell him. He's my Black family, I'm his. And then, like, a few hours later, I just texted him a picture of Joe Banks and just said, “This is your grandfather.” Um, and I just left it at that and he, you know, he didn't say anything, but I thought it was just so important for him to just see. I mean, the young folks call it “receipts.” Right? But for him to just have a picture of his Black grandfather on his phone…

Caryn: And I guarantee he saved it, I guarantee he saved it.

Rebecca: Yeah, yeah. I was thinking about something that you had said in the earlier conversation about how, if Kofi appeared on your door, I mean this was earlier on, you would be welcomed inside, which of course means everything to me. But also now that we've seen what this virus can do, in particular to Black folks, do you feel the same way about welcoming him?

Caryn: Yes. Yes. I even checked in with Anwar. I said, “Anwar, um, it's been a couple months and there are people we haven't seen in months. Are you cool? Like, are we still a home away from home for Kofi?” And he said, “Yeah.”

Rebecca: Yeah.

Caryn: Like, yeah. Because they see each other like distant cousins. But when we get together, we just chill and it's a given, it's just a given.

Rebecca: I loved, one of the things that I loved was how that small little anecdote in the, in the initial conversation we had where you were noticing that you and Anwar have this time together. Um, and I mean, I also have written about and reflected on how there's something so beautiful about being able to be in-company with your child. I mean, not since they were babies, right, have we spent this kind of time watching them grow.

Caryn: Correct. And watching them eat, watching all that eating.

Rebecca: They eat more.

Caryn: Yes. But it’s been a good time, you know, I’m grateful that for a number of reasons, none of which I planned, I just happened to have been home a lot more over the past four years than I had ever been in Anwar’s entire life. So, because I work for myself, I'm home. And then Anwar is the satellite that goes in and out, and in and out, you know, right, when they were doing school regularly. But for us both to be home, it's kind of like that entity that's probably most delighted is the house. It's like, thank you. It's kind of breezy in here. It’s kind of airy in here.

Rebecca: Thank you for living in me.

Caryn: Yes. We’re in here. We’re living. We don't mind each other's company. Um, he's tired of my food. I'm tired of cooking for him, but everything else has fallen in the line. We're good.

Rebecca: Yeah, I know. And, so now, like, the added chaos and intensity of the rallies and the protests. I mean you just — in a recent episode of the podcast, I'm talking with a First Nations author and an activist, and, you know, talking about this notion of, of apocalypse, you know, like he, he writes about it in his fiction, but he also references how Indigenous people and First Nations people have sort of experienced apocalypse already.

Caryn: Wow.

Rebecca: And I was just thinking, like, how this virus that is disproportionately killing Black and Brown people and then confounded by these rallies in protest of Black violence. It's like, maybe this is the apocalypse.

Caryn: Maybe this is it. I can tell you that I think there are people that are hopeful that a critical mass of Black and Brown people would just disappear. Oh, I believe that.

Rebecca: Oh, I do too.

Caryn: But I just don't think it's going to happen. ‘Cause I, I, this just, isn't the worst we've been through. So it's reckoning time, in the midst of feeling very comfortable saying that my Black life matters. Right? And, and, and all of them do. And they deserve that shout out. I'm also keenly aware that the forces that be are still excluding other people, even as we push for the Black community, there are still people whose voices who aren't even being referred to. And we're still doing this binary thing. This white folks, Black folks thing. And so, you know, I appreciate you just giving those voices air and your ear.

Rebecca: It's also wrapped up in what's probably going to change all of our lives in just extraordinary ways in a few months' time with this election. Um, how do you feel like this experience over the last four months has changed? Your sense of hope or what you think we need in a, in a president or are you just like a lot of folks, like we just need to get Trump out.

Caryn: Uh, I definitely feel that, but I have been more curious and more convinced that we need coalition government, like other nations have. This binary, again, you know, the binary thing it's not working. So this Democratic/Republican thing, it's not working. It's not working because even if the candidate that I intend to vote for, Joe Biden, gets the presidency, he's going to be met with a whole bunch of roadblocks that have been laid to trip up the next frame. It's just, it's absurd. It's absurd regardless. I'm not sure what progress looks like. I've even heard folks say, “You could expect for it to actually get worse if Joe Biden is elected.” So I'm sick about it. I recognize that I have to do daily social action through the election. I recognize that the Montgomery Bus Boycott was an excess of 380 days. And I'm going to have to have at least six months in me of daily action of some sort, no matter how big or small. However, this election I'm so deflated. I'm so deflated because now I've recognized that the problems, that this nastiness is looking back over the “saying her name,” “saying his name” and the folks who have died have died under multiple administrations.

Rebecca: Yeah, that is something, I mean, you don't hear in that specific, concise away. I mean, people know and say and acknowledge that it's been decades, but under multiple administrations.

Caryn: Yeah. Democrat, Republican, Democrat, Republican. So what am I? I'm not excited at all. I'll be there. We voted, we voted in April. I'll be there, but I'm not hopeful. I'm for coalition.

Rebecca: What does daily social action look like for you? Because I know that you guys have been out, um, protesting. I have been just doing my work, which…

Caryn: I don't know why you say “just” doing that because the writing and the… I mean, no, don't, don't make it small, honey. Um, my little, my Juneteenth celebration was running around with the Black women in my run group to different Black-owned businesses and this morning. So we just made our run, like, uh, hitting different Black-owned business spots, taking pictures and supporting them this morning.

Rebecca: I love that.

Caryn: Yeah. So that's what we did. But, um, I've also gone flat on social media.

Rebecca: Flat, how? Like, you don’t have the energy for it?

Caryn: I’m discouraged. I’m discouraged.

Rebecca: Yeah. Okay.

Caryn: Let’s say, I say something and you're like, “Wow, that's a really good point,” or, “that's thoughtful, you should share that.” I don't have any faith in sharing it on social media. I don't.

Rebecca: I recognize that, I really do. As someone who is, I don't mind saying, far more social media savvy than you are, I would say that it actually, is part of, it's a integration process of your entity, of your identity, of the work that you do for whomever follows you, whether it's the parents that you help, the folks that you work with who follow you, they take that little bit of whatever it is that you said into the next conversation they have. That's the entire premise of this podcast, right? It’s that people come through and have a conversation and they hear something that they can bring with them to the next. That's coalition, building. You have to look at social media that way, otherwise you will go flat.

Caryn: Well, you just gave my sail a little air. I feel myself pumping up. So, you refresh me. You refresh me. Thank you, honey.

Rebecca: I do my best, girl.

Caryn: Yep, you do.

That’s Caryn Rivers. She’s an education consultant, and the founder of Pathfinder Placement, which develops youth leadership curricula and helps families with school choices.

Oh, and that vacation with our families we had to postpone… it’s back on. We’ve all been in lockdown mode for the past four months, and doing the social distancing and all the precautions. So we’re leaving today — proceeding with love and big picture awareness.

And that’s it for this season of Come Through. I am so deeply proud of this podcast and the conversations we were able to highlight. While the country has currently turned its focus to addressing systemic racism, I’ve been confronting issues surrounding systemic racism, both personally and professionally, throughout my entire life. So it’s been very rewarding to have this platform as a way to further interrogate those issues. But more than that, it has allowed me, to quote the revolutionary poet and essayist June Jordan, “to invent the power my freedom requires.”

Thank you so much for listening — and please, keep having these conversations.

Christina Djossa produces the show, with editing by Anna Holmes, Jenny Lawton, and Tracie Hunte. Our technical director is Joe Plourde, this episode is mixed by Jared Paul, and the music is by Isaac Jones. Special thanks to Joanna Solotaroff and Jennifer Sanchez.

The folks who worked on Come Through were an absolute dream team. Each team member brought such dedicated joy and professional insight, and never backed down from the challenge of making a show that was premised on having difficult conversations. Thank you all.

I’m Rebecca Carroll - you can follow me on Twitter @Rebel19 for all things Come Through.