10. Don Lemon is a Soldier for The Army of Truth

I’m Rebecca Carroll and this is Come Through: 15 essential conversations about race in a pivotal year for America.

When I was little, I was determined to write myself into existence. I wanted to tell and read stories that included me, along with other people who looked like me. I was raised on Frog and Toad, Amelia Bedelia, and Beatrix Potter, and while I loved these stories, I never saw myself reflected in their pages.

Later, when my parents began to get the hefty Sunday edition of New York Times, I became obsessed with the Style section, the Magazine and Book Review, and William Safire’s column, On Language — I loved the nuance and mash-up of fashion, culture, art and books. It was a dispatch from New York City, where I dreamt of moving one day. But still, no brown-skinned faces, or stories about black people like me.

I didn’t set out to become a journalist, I only knew that I wanted to write as a way to understand the truth and meaning of things. From as far back as I can remember, it has always felt imperative to use language as a tool to broaden the scope of the world around me.

All throughout my childhood and in high school, I wrote short stories and plays, essays and research papers. So when I got to college, and a professor encouraged me to consider writing for the school paper, it seemed like a natural evolution. I never anticipated that when I pitched stories pertaining to anything black, I would be accused of pushing an agenda, nor that this accusation would be a recurring theme that would surface well after I’d graduated from college.

I’m not a traditionally trained journalist — I didn’t go to journalism school, but I believe that being a journalist is about telling the objective truth and reporting the facts. What I didn’t know until I started my career in media, was that what is called “the objective truth” was established without me or anyone else who looks like me in mind. The concept of journalistic objectivity comes from a completely white male standard of values and normative truths. And the facts, particularly in this era of “fake news,” are suddenly considered subjective.

In recent years, I have leaned into my role as a cultural critic and opinion writer, because it started to feel like the bosses in newsrooms where I was working were only ever going to see my ideas, observations and reporting as opinions anyway. But this is where things can get tricky. Where is the line between opinion and fact if you are a black journalist in America?

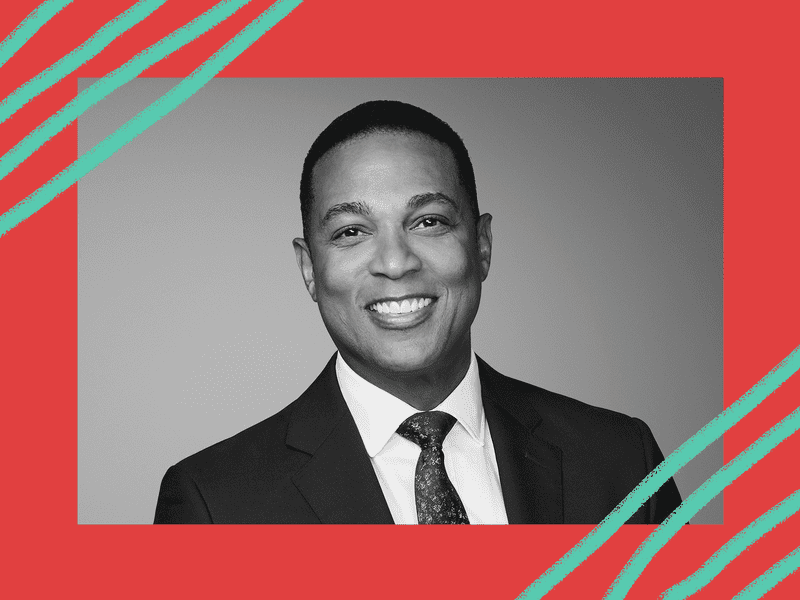

This is why I wanted to talk with journalist and CNN anchor Don Lemon. Over the past several years, we’ve watched Lemon’s trajectory from a semi-conservative broadcast journalist to an emotionally expressive, openly opinionated public figure. It’s a notable shift from being accused of engaging in respectability politics to calling the President a racist on live air.

And by the way, the President called him “the dumbest man on television.”

Lemon is an award-winning television journalist, and host of CNN Tonight with Don Lemon. In April, he and political commentator Van Jones launched the first edition of a special series about the coronavirus and race. It’s called The Color of COVID — there have been two episodes so far, with more expected in the future. The show features conversations with celebrities and experts about the devastating and disproportionate impact of the virus on people of color.

Lemon is surprisingly open about his opinions on certain points — such as when he will and will not use the N-word in his work. So I was curious to hear from him about his understanding of, and commitment to, journalistic objectivity... If that concept has changed for him, and about the expectations and pressures he’s faced as a gay, black male journalist who has willed himself into existence and onto the TV screens in our living rooms.

Rebecca: Hello, Don Lemon.

Don: Hi, how are you?

Rebecca: Thank you so much for taking this time to talk. I'm really, really thrilled. So I saw this clip of you from when you were a guest on Jimmy Kimmel last year, and you said to Jimmy, “You do the same thing that I do, but you do it with humor.” And I was thinking, “What is it exactly that you do?”

Don: I think that I inform people and I like to think that I make them think. I try not to beat them over the head with the information because I think that it's a really tough time in the country, even before Covid-19 when people are dealing with a lot. So, um, I like to think that I'm a truth-teller and that I'm an informer. And that I’m a soldier

Rebecca: A soldier… who, or for what?

Don: I'm a soldier for truth because, and information, because in this time right now, people don't know what to believe. And there's often a lack of information. I think people are just exhausted because they really don't know what to believe in. And I think that, um, that journalism is under attack. And I think many times people don't know what to believe because the administration likes to refer to us as “fake” all the time. And that we're not giving, you know, giving people true information, which is not true. We are. And I think that we have to hold steadfast and give people information and that's the true role of a journalist, whether people like it or not, whether the administration likes it or not. And that's what I do. So I am a soldier in the army of truth.

Rebecca: And so before we get into sort of journalism being under attack, and I do want to get to that, I would love to just know how you got into journalism and how you chose it. And were you always a news junkie?

Don: I was always curious. I don't know if it was always news, but I remember growing up as a kid, and I remember in the background, the television always being on, and in those days television was always on a stand, either on the floor or on a dresser. Uh, as we call it, the bureau, you know, we had a high bureau, then there was a low dresser. So the television was either on the high bureau or on a television stand and the Watergate hearings would be on, in the background, uh, or news about Vietnam, or my cousins or relatives who would be coming home from Vietnam. Or there was a, you know, a fuel shortage. The economy was bad. There were gas lines and on and on. And I would see all of that on television and I would be enamored by the news people and how they would give the information. So, um, you know, I think that I was more curious than anything. And I think secondarily, I was interested in the news people and how they conveyed and gave the information. So it's first Peter Jennings and then Max Robinson, and then later Bryant Gumbel.

Rebecca: And so what was it about their presentation that was more appealing to you than, say, an actor on a nightly show?

Don: Well, I, you know, don't get me wrong, I love actors on nightly shows, but there was just so many of them. Right? And they would sort of come and go, so the TV shows would come and go. And I would have my favorite person and, you know, it would be whoever was, you know, would be Emergency! or, some of these shows were before my time, but they were in reruns or one Adam-12 or, you know, something like that. Or The Brady Bunch, or what have you. And those shows would come and go, but there were so many of them, but the news people would be steady and they would be there all the time. And then, so then my grandmother would, she was a news junkie. She would have the soap operas on during the day. And then she would make dinner and then she'd watch the news in the evening. And so, um, she always had the TV on. And then at night we would listen to radio shows because the television would go off at midnight. And if we happened to be up that late, or in the middle of the night, I would wake up and I'd hear the radio. Um, we'd hear like KMOX, I think, out of St. Louis, Missouri, and we would just listen to news radio. So I think my grandmother's interest in news, um, she was a big influence. And so it rubbed off. So that's how I became interested. And so the, but the news people were steady. They were there every night, and it was just one or two or three of them who were always there for years while the people on television would come and go. So, there you go.

Rebecca: When I was coming up in my own career I also loved the idea of, of telling the truth. Um, but I never really understood when white editors or bosses would accuse me of pushing my agenda. When I pitched stories relevant and or a value to the black community… I remember distinctly pitching a story on how white consumers of nineties black hip hop affected the emotional health of black America and was shot down by my boss who said I was only interested in hip hop because I'm black. Um, is that something that you can relate to and that you experienced earlier on in your career, on your way toward CNN?

Don: Yeah, well, of course. Um, especially if you're a minority or if you're Latino, if you're African American, if you're Asian, if you're a woman, you experienced those things that you find that are important to the people in your own community or the people you relate to, and the larger culture in the newsroom may look at you, you know, especially in those days. Now it's a little bit different because people, you know, there's a, there's a little bit more diversity in newsrooms, but back when I was coming up, there wasn't a lot. I remember when I would try to pitch stories on HIV and AIDS in the black community and people would look at me like I had three heads. First they would say, “Well, you know, eight, oof, that doesn't rate. People don't want to see that. It's too depressing.” And then, you know, and then I would say, “Well, it's killing people in the African American community more than any other group, you know?” And it's like, you know, all of those statistics that you give and they would say it's kind of too niche. And so, um, at one point I had to go off to another country and do like my own documentary on HIV and AIDS in Africa in order to bring it back and tell a story about that and also incorporate the African American community in America. It was just, it was a strange thing like that people were so interested in how exotic Africa was that I had to go and do that in order to bring the black community in America into the news. It’s interesting how I had to do that.

Rebecca: And were you out at that time?

Don: I was out to my friends and myself, so to speak, but I really didn't talk about it. And I remember, um, my news director bringing me in and he thought it was an issue because people in the newsroom were gossiping that I was gay. And he brought me into his office and he says, “I think that you should know that people are saying this as if it was a big deal.” And I looked at him like, “Uh, okay, like is this supposed to be a thing?”

Rebecca: What thing? What was the thing it was supposed to be?

Don: It was supposed to be a thing that he was concerned that someone who was one of his main anchors, that there were rumors that I was gay and if I was gay was an issue and if I wasn't gay, it was an issue. And I just didn't understand why there had to be some big meeting about whether I was gay or not, and rumors I didn't really care. And I didn't really get it because for him, as a manager, all he had to do was say, “That is none of your business, and stop gossiping if Don is gay or not. That's none of your business. Do your work. And if he, even if he is, that's fine. And if he isn't, that's fine and that's none of your business.” But it was an issue and he just didn't really know how to handle it.

Rebecca: Did it concern you that he might have thought your being black and gay was a form of pushing your agenda on the AIDS or HIV story?

Don: No, I don't know if it was, I don't know if the two were together because I think by the time the HIV/AIDS story came around that I wanted to do, that I had, um, I had, um, a little bit more self possession, you know, in that particular newsroom and that I had, I had empowered myself a little bit more. But in the beginning it was certainly something that I did not, although I wasn't ashamed of it, I just didn't want to have that, I just didn't want to have another strike. Like, I don't want to have another issue. Like, okay, I have to deal with the black issue. And then I'm going to have to deal with the gay issue. It was just like one more thing. You know what I mean? And then I remember I went out on a date with someone who was also in a high profile position in the city. And my gosh, it was a thing like… Oh my gosh, if you guys are going out, it could be a thing and they can write about it and maybe it'll be a conflict of interest. And I reeled off all these names of these very high profile people in the city who were dating and who had married and whatever. And I said, why is it a thing if I'm going out with somebody? It was just, it's, you know, this was back in the early 2000s when people were just really ignorant about it.

Rebecca: Still, I mean, the early 2000s… You make, you make it sound like it was like the 1800s. I mean, you know what I mean? Like, at that point, at that point, people really should be a little bit more hip, you know?

Don: I think when I was in New York it may have been a little bit different. But you know, I was in Chicago, I was in the middle of the country and things were a little bit different then. But I mean, I think things have changed, things have progressed really quickly now. I just remember feeling very oppressed and like I had, I felt like I was in the 1950s.

Rebecca: Yeah, yeah. I mean, it was interesting that you sort of paused and struggled for a minute to find the right word to describe what it meant to have another thing, another strike, another handicap. Right? I mean, for us that we have to sort of search for those terms. And at what point do you feel like you were like, “You know what, they're not strikes. They're not handicaps. I am a gay black man and I do my job well, and that's that”?

Don: Well, I feel that way now. I mean, um, listen, I, I don't think you get any, I don't think there's anybody else on television news like me. I mean, you know, I don't want to, I hate to sort of toot my own horn or whatever, or pat myself on the back. That's not really what it is. I'm just being honest because I'm the only, I'm really the only person of color in prime time on cable and gay. Rachel is, you know, Rachel Maddow is on, Rachel is a woman. She's not a minority, but I don't think there's anybody else now that I can think of. So, and prime time cable, it's just me. And so I've had to develop this thick skin, but it really is tough because the standards are different for me. You know, I find myself getting criticized for things that people do and say, and for whatever that people don't get. I remember when I first started in my position, and, you know, I would do things on the N-word, which nobody was doing. And I would get hit from the, you know, the black community and I would get hit from the whites and I would get hit whatever. I wasn't black enough for blacks, and then I was too black for whites. And I was just like, “Oh my God, I can't win.” I think that the, the… If you read the blogs and if you read the criticism of me, I think a lot of it is rooted in homophobia and racism.

Rebecca: You think? I'm sorry, I mean, as a black woman in America, I'm like, really? Yes, I understand. I get it. I get it.

Don: All you have to do is go on and you will see that every single comment is either about some sort of gay act or sexual act about me or something about being black. Uh, either I'm a race baiter or it's some sort of homophobic thing. And after a while it's just like, why do I even bother? So, you know, and I think there's, you know, even the president of the United States who likes to call me the dumbest man on television or dumb or stupid or whatever, he likes to call me, or, you know, a low IQ or whatever it is. Where does that come from? So I deal with it, I accept it, and that's what it is. But I don't let it, I don't let it stop me.

Rebecca: Do you feel like this idea of neutrality or objectivity or, you know, the sort of tenants of journalism, traditional journalism, are being challenged or forced to change under this administration?

Don: Well, here's what I think. I think, I think that there's an objectivity trap, right? That if you don't call this president out for what he is, then it's a trap. Like, if you say, “Well, the president lied about this, and if you constantly tell the truth about this president, about what he does in this administration, that the administration isn't telling the truth about this, the president isn't telling the truth about this.” If you do exactly what you're supposed to do, then you, they cast you as biased and not objective. And that is a trap because it is, it's not true. You're simply pointing out what the truth is. And so if the president is doing something that is racist, if he is exhibiting racist behavior, it is incumbent. Not I think, I know it is incumbent on journalists or a journalist to point that behavior out. And to say what it is. To call racism, racism. To call a lie, a lie. And if you do that you are doing your job. And so I think that the media has to be constantly vigilant not to fall into a fake objectivity trap, that you have to give some extra sort of leeway to an administration that is being overtly racist or overtly lying to you all the time. And pretend like, “Oh, I have to, like, give them the benefit of the doubt that they're not lying when all the evidence is there that they are. I have to give them the benefit of the doubt that they're not being racist when all the evidence is there, that they are being racist. I have to give them the benefit of the doubt that they're not misleading the American people when all the evidence is there, that they are misleading the American people. I have to give the people their spokespeople the benefit of the doubt that they're not standing there at a podium or in front of a camera and lying to people when all the evidence is there that they are.” That is fake objectivity. And I think that a lot of people have fallen for that. When people say, “Oh my gosh, you're biased.” You're not being biased. When the truth is not on your side, meaning when the truth is not on the administration side, it can look like a news organization is being biased when they're actually not. They're just pointing out what you're doing and you don't like it.

Rebecca: You just had a total James Baldwin moment there. You know, that famous interview when he's on Dick Cavett and he's talking about, you know, the difficulty of people believing the truth from the mouths of black people.

Don: Yeah, it’s… They tell you what, when they say it's an alternative fact, an alternative fact… An alternative fact is an alternative reality, which is a lie. They tell you what they're doing.

Rebecca: I'm just wondering, ‘cause I, I know that you've talked about, um, as you said earlier, the N-word. And, you know, been very sort of consistent in terms of your integrity about the use of that word. Um, and I just wonder how as a black man, as a gay black man, as a journalist, what role does the interrogation of language play in the work that you do?

Don: So for me, it's really important because it doesn't, it language for me, it's not, it's not always black and white, but it is black and white. Because as a, as a journalist who happens to be black, when the, the language in our society now as it comes to, when it comes to the N-word, and when it comes to calling people thugs, I think that that is important to interrogate because it doesn't mean the same thing to all people. And I think that's one of the, I think that's, it's an important reason why I am here. Because not everybody, it doesn't mean the same thing to every single group. And not every single group understands the language in the same way. Um, I was watching, I was just watching a story about the guy who was, um, trying to deliver in a neighborhood. It was a black driver, a delivery driver, and it was a white man who lived in the neighborhood and said, he was finally, said he was head of the neighborhood watch or something. And then he went to get another person and the guy was trying to explain to him that the reason he was in the neighborhood is that he was delivering something. And the guy said, “Well, I don't understand how you got in.” And he says, “Don't I need a code to get into the neighborhood?” And he said, “Well, yeah.” And he goes, “Well, don't you think I wouldn't be in the neighborhood if I didn't have a code to get into the neighborhood?” And they just kept going back and forth. And just, it was like another citizen's arrest and they were trying to explain to him why they were stopping him and they were each talking over each other's heads with their language because this one group thought that they were police officers because they live in the neighborhood and they thought it was their role and their, but they were just talking over each other. They were not understanding each other's language. What was coming out of their mouths and also their physical expression of their body, their body language as well. And I kept saying, they don't understand each other at all. The words that are coming out of their mouth don't have the same value and they don't understand each other.

That’s Don Lemon. Coming up — when he’ll say the N-word on TV and when he won’t. That’s in just a minute.

Rebecca: Alright, I want to talk to you about, um, some of the L’s that you've taken and moments that may have felt or been perceived as maybe, you know, having failed the black community? And I say this as somebody who has been dragged by black Twitter. We judge as hard as we love, but we're always welcomed back into the fold. What do you, what do you make of all of these, um, “welcome back to the cookout memes” on black Twitter about you?

Don: I look at it in the way, I don't read my own press and I don't believe my own press. I just kind of do what is right and if someone wants to make a funny meme out of it, then I think it's great. If someone wants to make a, you know, a mean meme out of it, then I think that's okay too. But, um. I've always, uh, you know, I sort of remain the same person. But I think it's, I think it's only natural for anyone in any position to grow into a position. So, you know, if people in the black community think that I have grown into my position as a better representative of them than I accept that. And I think that's great. Um, but I, you know, um, I've always been me and I've always had the best interest of the black community at heart. Whether African Americans or people on Twitter, on social media, thought it or not.

Rebecca: Did you feel unwelcome at the cookout before? I mean, I'm a, I'm a sucker for, for an evolution, you know, especially when it comes to race. So I'm, I'm very curious to know it had to do with you being gay?

Don: Um, well, I think there's a lot of that. Listen, there's a lot of that in our community, and let's just be honest, but there's a lot of that in every community. I mean, I, there's a lot of that in the white community. There's a lot of that in the Asian community. There's a lot of that in the Latino community. Um. And, but you know, I am a black man, so I see it. It is magnified in my community because that's the community that I, that I relate to and that I, um, draw on for support. And, um, and that's the first community I look at for support and for acceptance. So it hurts when it more, when it comes from the community. So don't get me wrong, you know, I'm not going to say that I didn't, I wasn't affected by it. But does it hurt? I have a very thick skin. Um, no one ever likes it. “Oh, you can't come to the cookout in person, the echo chamber of the internet or the, you know, social media.” I'm sure people said that, but it never affected my ratings or it never affected my job or, or anything like that or anything in person. Um, I think the only thing, the only thing that it did affect, which was surprising to me, and I've never really spoken about this, was my relationship with the National Association of Black Journalists because I had been a big proponent of the National Association of Black Journalists. I tried to help them and do, you know, and help black journalists. I'm always helping journalists, if any. I don't care what color you are, what background you are. I try to help you because I think that's what we're supposed to do. But, uh, I think the black journalists, like, wrote a letter or something about something that I did and, and whatever, instead of like reaching out to me and calling me and asking me what was going on, they decided to write an open letter and published it.

Rebecca: Do you remember what it was?

Don: It was something that I did about the N-word. I think it was… I remember it was a time they were taking, it was the Confederate flag and the N-word. They were taking the Confederate flag down in South Carolina, and it was this controversy about the Confederate flag, and then it was the N-word. President Obama actually said the full word on a podcast on, I forget who it was, it was maybe Marc Maron's show or something like that, and he said the word. And so I opened my show. And instead of saying the word, I was like, wow, that's, that's heavy. And I have said the word before. I've always said that you should say the word, you should use it judiciously. Like I don't like just saying it in songs. That's up to you. If you want to say it. I just don't like bastardizing that word. But I think that if you want to, like, in a police report, if you're reporting on something, I think that you should say, the person said, you should actually say the word because they didn't say “N-word.” They said the word. And so I think we should feel the full impact of that word if you're a journalist and it's something of record. And so I said, these are the two. I opened my show and I said, “These are the two big stories in our country right now. These two things offend people. Does this offend you?” And I held up the Confederate flag and then I said, “And does this offend you?” And I held up the word and I didn't say it. And, like, everybody came for me. And so they wrote a letter saying that saying something like, “I can't believe this is, this is so offensive. I cannot believe, I'm where you know, this is not, a journalist should not be doing this.” And I'm like, wait a minute. You guys say, you, we say this to each other. We say it in songs. I'm a journalist. I held it up. I didn't even say it. Why aren't you writing this to the president of the United States who actually said the word on a podcast?

Rebecca: But also your argument, uh, when you got into it with, uh, with the journalist and lawyer, Sunny Hostin, who I recall was just livid. And she said that you should use your journalistic conscience and not use the word, which I don't know. I, I felt like you made a pretty good argument, which was that the way that Barack Obama used it, he wasn't calling anybody that, he was making a point in the context of race and racism in America. And I just, I feel like this policing of each other though… What do you, what do you, where does that come from?

Don: I don't know because I'm not the word police, but I can certainly express my opinion and say, “God, I don't like it when you use that word gratuitously and I'm not going to castigate you for using it.” But I'm not going to say, “You cannot use that word. I'm so offended that you use it.” I'm just going to say I would prefer not to use that word gratuitously because that really bothers me. But if you are a journalist, if you're using it in a context that you need to use it, then by all means, I think that you should use it. And I think again, that you should feel the full impact of it. I am a journalist of record. Let the record state that this is what was said. “N-word” is not what was said. I feel an obligation that I have to say this, just like it's, it's almost like a legal proceeding. And so, um, it didn't quite understand what Sunny was saying. And I think now if you talk to Sunny, I think she probably has changed her tune when it comes to that. I think that she has, she's probably grown now when it comes to that word. Um, and I don't, and it's weird because I didn't think that we were actually saying anything that was that different. But, who knows? Maybe, maybe she just wanted to have an argument on television. I don't know. I have no idea.

Rebecca: I think with that word, the tensions are so high and the emotional resonance is just incomparable, really. So I want to talk about something that you’re working on right now. Tell me about The Color of Covid.

Don: Okay. So this has been a thing for me because I have been sitting here almost every night since it started, reporting about, you know, this, this pandemic, this thing that's been killing people and that has been attaching itself to people and no one knows what's going on. And all of a sudden, we get these statistics that 60% of the deaths, uh, in many areas has been African-Americans. Okay. And I, why? And the president wants to open up the economy and all these things, and you wonder why is, you know, almost 60% of the people, why are African-Americans dying at an alarming rate? And more often than anybody else? And it is because we're in contact and in the jobs we're where we have to touch things and be closer to people and we have to take public transportation. And we're, and you know, the bus drivers and the cafeteria workers and the janitors and so on and so forth. And so we come in contact with people who, and with surfaces, that may be contaminated more and were in places that, you know, the air may not be as clean. And we live in food deserts and we have, um, underlying conditions and so on and so forth. And so it just exposes another place in the world and in our society where African Americans are at the bottom wrong. And, and so for me, that just bothered me. So we did a Color of Covid when these, all these numbers started coming out and I just went to our management and I said, “We have to meet the moment and we've got to do this. And we have to tell people about how to protect themselves and how to be better and what to look out for because it's not just health disparities. It's health disparities, plus. It's not just living in dense areas. It's living in dense areas, plus. it's not just institutional racism and conditions and all of that. It's all of that, plus. It's a number of things that we need to figure out how to deal with. That's what we talk about on the Color of COVID, and I think that we're going to end up having more than just one more. We'll end up doing several more because, um, how can you justify being 13, you know, 14% of the population and having 60% of the deaths? It's just not justifiable.

Rebecca: And so what do you hope is the biggest sort of takeaway for people who've watched the series? And I'm glad to hear that there'll be more than one.

Don: I think the biggest takeaway is awareness for everyone. For the larger culture, for everyone, for people to understand that the people that you're, who are keeping everything going, the people who are conducting the subway, the people who are changing the bedpans, the people who are cooking the food, the people who are doing all those things, are people of color. They're keeping your cities going, they’re keeping the hospitals going. Those nurses out there, many of them are people of color. A lot of them are people of color. A lot of them are people of color. So having awareness about that. But I also want self-empowerment to be a part of it as well, for people of color, for black folks to learn something about how to improve our particular situation as well and not become victim to Covid-19 or any other disease.

Rebecca: Don, thank you. I mean, I appreciate it. I so appreciate you and all that you do.

Don: It was such a pleasure. Be well and be safe, okay?

Don Lemon is the host of CNN Tonight with Don Lemon. His series with Van Jones about the pandemic is called The Color of Covid. Christina Djossa and Joanna Solotaroff produce the show, with editing by Anna Holmes and Jenny Lawton. Our technical director is Joe Plourde, and the show was mixed by Isaac Jones, who also wrote the music. Special thanks to Jennifer Sanchez.

I’m Rebecca Carroll - you can follow me on Twitter @Rebel19 for all things Come Through - and - if you liked the show, please rate and review us.