What If I Could Have Grown Old With My Brother?

( Kia LaBeija )

KAI WRIGHT: You were just saying no one has ever asked what if, what I, what were you about to say about that?

JOYCE RIVERA: Well, no one has ever asked what if there had been no HIV epidemic. Right. No one's ever said that. Not to me anyway, I've been around long enough. What if, what if I could have grown old with my brother? Hmm. That's, uh, something that I, uh, miss. Sometimes I'm at home and whatever, something happens, you know, and, and I wanna get up and call someone. And I realize that my entire immediate family almost entirely is missing.

KAI WRIGHT: What IF HIV had shown up in the U.S. and we stopped it? Could we have stopped it? Joyce Rivera is from the South Bronx — which is a place where both HIV and drug addiction remain enormous challenges.

[Sound of office at St. Ann’s Corner of Harm Reduction]

KAI WRIGHT: She is someone who's thrown her entire life into stopping the spread of HIV— and through her work, she has saved thousands of lives. Unlike in Harlem, where we were for the last episode, where some people were very reluctant to speak up, Joyce Rivera took action as soon as she understood what was going on in her neighborhood: in the South Bronx.

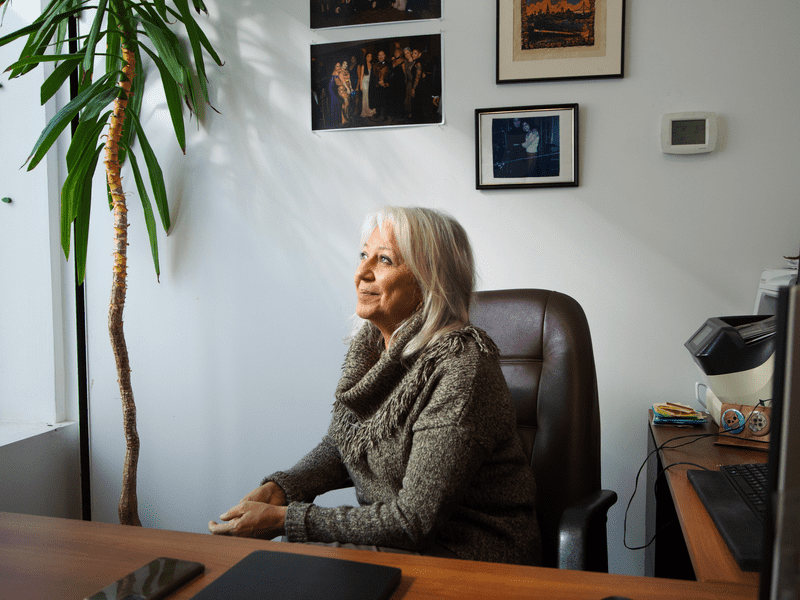

And today, decades later, she still runs a syringe exchange and what she calls a health hub there — they provide all kinds of services — it’s called St. Ann’s Corner of Harm Reduction.

[Sound of office at St. Ann’s Corner of Harm Reduction]

KAI WRIGHT: But Joyce Rivera wasn't a public health leader back when the disease first showed up in her neighborhood, and in her brother. In her office, there's an old photograph of them together.

JOYCE RIVERA: It’s an old NYC apartment, you see the radiators and wall to wall curtains in the back

KAI WRIGHT: It’s Christmas time — you can see a Christmas tree off to the side.

JOYCE RIVERA: And of course it’s in the '70s — and he has pretty long hair. He has his arm around me and I have my arm around his paste. It’s a picture of pals. We were pals.

[MUSIC]

KAI WRIGHT: Um, do you, I assume you do know how he got sick in the first place?

JOYCE RIVERA: Yes, he was, he was, it was injected related. He engaged in petty crime that led him to land up at, uh, at a prison upstate, and there, he started to inject and there, they were sharing, you know, one, one work.

KAI WRIGHT: One needle. Among all the people in Carlos's unit. It was the early 1980s. And when Carlos was released from prison, Joyce Rivera noticed he was weak.

JOYCE RIVERA: My brother, uh, started to develop symptoms. And I've been watching the news and I'm matching up the symptoms with what he's experiencing. And one night, I get up in the middle of the night and sitting at the pot, it hits me and I just bend over and sob, because I knew that he had it.

[MUSIC]

KAI WRIGHT: From The History Channel and WNYC, this is Blindspot: The Plague in the Shadows, stories from the early days of AIDS and the people who refused to stay out of sight. I’m Kai Wright.

What could have saved Carlos and thousands of drug users in the South Bronx alone? Joyce Rivera is going to walk us through her decades long effort to find an answer to that question.

In this episode we look at the heroin epidemic of the 1970s and ’80s, and how big a role it played in the spread of HIV.

The story actually begins way before HIV had an actual name.

We know, when AIDS came into public consciousness in 1981, it was described as a gay man’s disease. But for people who were interacting with drug users, the signs started popping up years earlier.

In New York there was an agency set up in the 1960s — called DSS — the Division of Substance Abuse Services. Their job was to try to study drug use. Don Des Jarlais was a researcher there. And in the late 1970s, they noticed a huge uptick in pneumonia deaths.

DON DES JARLAIS: And we couldn’t understand what was happening, because pneumonia was a constant threat and all of a sudden there was an explosion of pneumonia deaths.

KAI WRIGHT: It was like five times the number of deaths as the years before. He told my colleague Lizzy Ratner, this just didn’t make sense.

DON DES JARLAIS: At that time, we were monitoring death certificates among people who injected drugs.

LIZZY RATNER: When you say at that time, do you mean?

DON DES JARLAIS: In the late ’70s.

LIZZY RATNER: So already in the late ’70s, you were seeing these pneumonia deaths?

DON DES JARLAIS: Yes.

LIZZY RATNER: Not like in the ’80s, you looked back, but in the 70s.

DON DES JARLAIS: We saw them in the late ’70s. They were not classified as pneumocystic pneumonia. They were just pneumonia. We didn’t, unfortunately, we didn’t look carefully enough to see that it was pneumocystic, but we saw a big increase in pneumonia deaths.

KAI WRIGHT: So this organization in New York that’s set up to study drug use saw something out of the ordinary. And, turns out, other people were seeing this same “explosion” of illness and death in drug users too.

[Sound of arrival at house]

KAI WRIGHT: There were big red flags on Rikers Island — New York City’s largest jail complex.

LIZZY RATNER: You clearly saw this …

SISTER EILEEN HOGAN: Well usually …

KAI WRIGHT: Lizzy went to visit a nun who had worked at Rikers, Sister Eileen Hogan.

SISTER EILEEN HOGAN: There wasn’t much communication …

KAI WRIGHT: In the late 1970s, Sister Eileen was a chaplain at Rikers — she worked there for nine years. She was the first female chaplain in the Department of Correction.

SISTER EILEEN HOGAN: Well, I went through another, uh, a logbook that I had. You know, like what I was doing every day.

KAI WRIGHT: Sister Eileen has notebooks from her time there. And she remembers spending most of her days in the infirmary ministering to sick inmates.

SISTER EILEEN HOGAN: And I was talking about how crowded the infirmary was. All I say is, it's crowded. It's very crowded. It's crazy here.

LIZZY RATNER: And that was already in 1978 that you're, it's crowded. ’79.

SISTER EILEEN HOGAN: Uh, ’79. That was in, uh, ’79. We didn't even call it a disease then. People would, uh, they couldn't gain weight. They were very thin. Um, and usually if people. Uh, came back in, and if they were just on drugs, they would kind of begin to fill out in two or three weeks, but these people, these women weren't, and it was a fact that the number of women up, up in the infirmary, because normally it wasn't packed, normally they didn't have to open more rooms for them.

LIZZY RATNER: And they had to open more rooms.

SISTER EILEEN HOGAN: They had opened more rooms.

KAI WRIGHT: So researchers studying drug users; a nun at Rikers; and then we met a doctor who spent most of his career in the Bronx.

[Sound of arrival at house]

KAI WRIGHT: Arye Rubinstein was also seeing something new — something he had never seen before.

ARYE RUBINSTEIN: Suddenly, in 1978 and ’79, even ’78 was one, the end of ’78, we saw patients that we could not figure out what they had.

KAI WRIGHT: Arye is on the faculty at Albert Einstein Medical Center and Montefiore Medical Center. He’s an immunologist — and back then, he was spending most of his work day dealing with test tubes, mice in a lab.

ARYE RUBINSTEIN:: And that was my life, actually, at Einstein from ’73 until ’78, I think, when suddenly there was an explosion of patients with immune deficiency that we didn't understand. And then I switched into the clinical part.

KAI WRIGHT: And he started seeing these patients and their immune systems seemed out of whack.

ARYE RUBINSTEIN: What they had is, they had huge lymph nodes. An elevated immunoglobulin. We thought that this is a severe immune deficiency. Most of them were from the South Bronx.

KAI WRIGHT: And why do you think that was the case?

ARYE RUBINSTEIN: Because I think this was an area in which, uh, drug use was uh, and there was a lot of substance abuse in, in men and also in women.

KAI WRIGHT: So you would assign it primarily to the drug epidemic.

ARYE RUBINSTEIN: I think that was the initial, uh, cause of the rampant transmission.

KAI WRIGHT: Arye was seeing all these patients — drug users and young kids — with puzzling symptoms, but he was also reading the medical journals. He knew that doctors around the country were starting to see something unusual in gay men in urban centers.

ARYE RUBINSTEIN: And I said, there must be some connection. uh, and I wrote the paper. Uh, it was rejected. I mean, the people of CDC came to us. and looked at our patients and did not believe that they have HIV. They said, it's possible. I mean, I'm not sure. They spent, I think they spent half a day with us going over the cases. Look, we had different opinions. I was convinced about it, and they were not convinced.

LIZZY RATNER: I guess one of the questions we have is would it have made a difference if people had listened more sooner?

ARYE: Well, I think concerning the epidemic, it would have made a difference because you could have prevented sexual transmission. You could have prevented transmission through drug abuse. But regarding treatment really had no tools at that time, there was no medications, but the spreading of the disease, uh, it may have made an impact.

LIZZY RATNER: Was there a particular blind spot that the medical community you think had that prevented them from recognizing what you recognized?

ARYE RUBINSTEIN: I think we are focused mainly on the gay community. They didn't look behind it, and they did not look at the substance abuse community. That happened much later. Other communities were just hiding it. In the substance abusing community in South Bronx, they were getting infection, dying from infection, dying from poverty, and did not go out to the press.

JOYCE RIVERA: Yup. He’s right. It’s exactly right. Who cares about the poor? And who cares about substance abusers. Nobody.

KAI WRIGHT: Joyce Rivera saw it all close up.

JOYCE RIVERA: It’s very sad. How do you allow this infection to be in the life blood of a community and basically, like just let people die, let people infect each other.

[MUSIC]

KAI WRIGHT: To really understand what happened — why and how the virus was able to flourish among drug users — it's worth taking a walk with Joyce Rivera through the South Bronx she grew up in.

[Voices on the street: Hi, how are you? Good, how are you? Thank you so much. Thank you so much. Oh, sure.]

KAI WRIGHT: On a rainy day, Joyce Rivera bounds out of an Uber and calls out as she opens up an umbrella to protect her head of silver and pink hair.

ANA GONZALEZ: I love the pink in your hair. Is it new? Is it always there?

KAI WRIGHT: Joyce Rivera meets our producer, Ana Gonzalez.

JOYCE RIVERA: I put it on occasionally and you know, I, I used to have it all purple. Ooh.

KAI WRIGHT: She tours us around her neighborhood.

JOYCE RIVERA: I really am a city kid. I learned how to swim there. In the pool? All the kids would come and we would go swimming. I was like 10 or 11. Would make sure it had 25 cents or 30. I'm gonna make, it really dates you, but you could get two little hamburger pads or pizza which was for us, like we would never, ever, you know, I come from a traditional home. We never ate out

KAI WRIGHT: Her parents had come from Puerto Rico when they were young. Growing up, she and her brother lived in the same apartment building as her grandparents.

JOYCE RIVERA: We had apartment four, apartment 16, apartment 17.

KAI WRIGHT: A whole family right there. Her parents were on the 5th floor; the grandparents on the 2nd. When Joyce Rivera's family got even bigger with 2 younger sisters, Joyce and her brother, they would go stay downstairs with the grandparents.

JOYCE RIVERA: The two of us were like two little puppies for the old people. And we were like two shih tzus running around the house. Very indulged by these old ladies.

KAI WRIGHT: There were four kids, but Joyce Rivera and Carlos — or called Carlito, as they called him — they were especially tight.

JOYCE RIVERA: We were a year and 10 months apart.

KAI WRIGHT: Always together.

JOYCE RIVERA: We played under the bed, we had fun.

JOYCE RIVERA: Her mom’s apartment was on the top floor of the building, right by the staircase that went out onto the roof, both of which were big hang outs for people getting high. Drug users were part of life in the neighborhood. They all knew Joyce Rivera and they all knew her mom, Nellie, and they trusted each other.

JOYCE RIVERA: And they would knock on the door and ask, they would say, Nellie, you know, Nellie, can we have some water? And Nellie would give him water and then they would, they would either leave or something bad happened. They would say, Nellie called the cops. And, and I would call.

KAI WRIGHT: But by the ’70s as Joyce Rivera finished college and started working, things had gotten worse. Some streets in her neighborhood just had become open drug markets.

JOYCE RIVERA: Brook Avenue was like a bazaar. So I mean, every, every car length there would be a different dealer, selling a different brand. When you walk, you would hear everyone hawking their brand, you know, Gucci, Dead on Arrival, Michael Jackson, you know, whatever. They had different names, different brands.

ANA GONZALEZ: All heroin?

JOYCE RIVERA: All heroin.

KAI WRIGHT: The Bronx became a central place for the distribution of heroin throughout New York City and a center for drug addiction too.

JOYCE RIVERA: Those were terrible years. Terrible years. And, um, the Bronx looked like no man's land.

KAI WRIGHT: People argue about which things were cause and which things were effect, but here are some realities about the late ’60s, and early ’70s that led to this moment in the Bronx: economic collapse across the city but particularly in poorer neighborhoods, like much of the Bronx.

JOYCE RIVERA: The fiscal crisis reduces the services, social services, health care services, by over 40%.

KAI WRIGHT: Jobs disappeared.

JOYCE RIVERA: And then we have a homeless crisis.

KAI WRIGHT: Landlords burning buildings for insurance money.

JOYCE RIVERA: The housing stock in the Bronx is burning for somebody’s else’s profit, so we ignored that.

KAI WRIGHT: And then an influx of drugs.

JOYCE RIVERA: So we ignored that. We sort of decide the Bronx can die on the vine.

KAI WRIGHT: In that moment, many responses were possible: more addiction treatment centers to help drug users; economic development to create new jobs; a robust social service network to provide support for struggling families. But that is not where the country was politically.

[ARCHIVAL AUDIO PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON]: America's public enemy number one in the United States is drug abuse.

KAI WRIGHT: This was from a speech President Nixon gave in 1971 — and it kicked off what became the war on drugs. Nixon set up the Drug Enforcement Administration — the DEA — in 1973.

ROBERT FULLILOVE: And it becomes clear that part of what we're gonna do to bring the problem of drugs down is think about not the public health issues of high rates of addiction and use.

KAI WRIGHT: Robert Fullilove teaches at Columbia University's School of Public health.

ROBERT FULLILOVE: No, let's think about how much drugs are leading to crime and make it a criminal justice issue. We don't deal with issues of addiction as a medical problem that can be managed if there are appropriate resources. No, we declare this a criminal justice issue: let me scare you away from drug use, by threatening you with many, many, many years of incarceration.

KAI WRIGHT: Eventually, states like New York passed laws making it illegal not only to sell, but to use any drug equipment. Like needles and syringes. And what that meant, in practice, is that you could get arrested simply for carrying around a needle. So just as a new virus lands in our cities — one that spreads through bodily fluids — you have a drug policy that ends up concentrating IV drug users in tight spaces with little access to clean needles. One was in prisons and jails: remember how crowded the infirmary was at Rikers? And another one was on the outside: in places like the South Bronx, drug users began to change where they would gather to get high.

ROBERT FULLILOVE: Addicts aren't stupid.

KAI WRIGHT: And dealers aren't stupid either. All those empty, often burned out buildings in the Bronx? They could be put to another use. Shooting galleries started appearing — abandoned buildings where drug users could rent or borrow needles and then inject heroin, right there, away from the eyes of the police.

ROBERT FULLILOVE: How about we take over whole buildings where it might be possible for you to come clean and buy product as well as your tools, injection equipment?

KAI WRIGHT: So the the law leads people to create shooting galleries, which is an irony, right? Like people didn't use to shoot up that way.

ROBERT FULLILOVE: They did not. They did not.

KAI WRIGHT: And shooting galleries brought together a group of people where needle sharing was common.

ROBERT FULLILOVE: Suddenly makes it possible for HIV to have a hugely efficient route through which it can infect other people.

KAI WRIGHT: By the end of the 1980s, the highest concentration of HIV infection in the entire country was in the South Bronx. Dr. Kathy Anastos was a primary care doctor there, at Montefiore Medical Center.

DR. KATHY ANASTOS: I don't think anyone saw that it would devastate whole communities, it would devastate the gay men's community. And it really did devastate the South Bronx.

KAI WRIGHT: She treated heart disease, diabetes, asthma, regular stuff, but a full half of her time was spent treating patients with HIV and AIDS.

DR. KATHY ANASTOS: Well, how much patient care did I do? Six sessions, probably actually probably 40 to 50 people in a week. It was the leading cause of death for people 15 to 49, 15 to 45 for a decade at least.

KAI WRIGHT: Injecting drug use had surpassed all other risk factors as a cause of new cases of AIDS in New York State. And the thing was, there was a way to change this, to slow the rate of transmission. And it wasn’t even that complicated. Remember the drug researcher, Don Des Jarlais? The guy who saw all those pneumonia deaths in the 1970s? He said he knew a doctor at the time who offered up clean needles in his office waiting room. He didn’t give us the guy’s name — it was definitely illegal back then.

DON DES JARLAIS: There, there was a long time between knowledge that the virus was being transmitted through sharing syringes, which was developed in the mid-eighties till New York City got, uh, syringe exchange programs in ’92.

LIZZY RATNER: What do you think the consequence of that delay was?

DON DON DES JARLAIS: Um, tens to maybe hundreds of thousands of unnecessary deaths.

KAI WRIGHT: That’s a world-wide figure, not just New York City, but it might have included Joyce Rivera’s brother, Carlos Rivera.

JOYCE RIVERA: Yeah, it was terrible. He died at, uh, New York Hospital. My brother was just 31 years old.

JOYCE RIVERA: What's that song? You ain’t heavy she’s my sister. He would sing that.

Mm-hmm. (laughs)

JOYCE RIVERA: That’s a beautiful song. I guess what I want to say is, for anyone that I love, I'm always going to stand up, always, you know, like be their best advocate. I didn't want my brother, Carlos, to just be one more on a heap of a pile of people. And I also didn't want the community to just be unremembered.

KAI WRIGHT: After all, it wasn’t just Carlos. She loses friends, a cousin, another cousin, many neighbors. So, Joyce Rivera charts a new life plan — when we come back.

KAI WRIGHT: You’re listening to Blindspot: The Plague in the Shadows. Joyce Rivera didn’t see anybody coming round doing anything to stop the mounting death toll in her neighborhood. It’s the late 1980s. HIV and AIDS are a leading cause of death in the Bronx at this time. In Harlem, a neighborhood with more political clout, needle exchange was a no go. That’s the story we told you in the last episode.

But there was nothing getting in Joyce’s way. She was studying political science in graduate school. She quit. And after her brother’s death, she looked around and decided: she needed to deal with problems closer to home.

JOYCE RIVERA: So when I look at people who've decided to do their own thing, I like those people.

KAI WRIGHT: Cause you're getting out of the straight jacket.

JOYCE RIVERA: Yeah. Because they, their resilience, comes from the power that they just say no.

KAI WRIGHT: She got a job with the National Drug Research Institute. She was a researcher, an ethnographer, on one of the first studies of drug use in the United States — and she ended up meeting a drug dealer, a guy who went by the name Cuzón. He worked with his cousin. And between them, they were bringing in about $3.6 million a year from their drug trade.

JOYCE RIVERA: The first time I met this man, I met him behind the barrel of a gun. Alright, to go down to meet this guy, one of his security guards had a gun, and I said to myself, Whoa, what did you get yourself into now? But it turned out all right.

KAI WRIGHT: I guess!

KAI WRIGHT: We found Cuzón at a prison in Pennsylvania. He is now serving life on 13 counts, plus 185 years on a slew of charges that would make Tony Soprano blush. Murder, kidnapping, distributing heroin, you get the idea. We wanted to hear his side of the story. What did he see in Joyce?

[Phone: This call is from federal prison. You will not be charged for this call.]

KAI WRIGHT: Cuzón has a case that is still pending, so he wasn’t willing to talk on record. But he told us he remembers Joyce. And she remembers him.

JOYCE RIVERA: He looked like a Latino man, my complexion, slender, someone who is burning a lot of calories.

KAI WRIGHT: And he looked like a guy with power — the power to make stuff happen in a place that had been abandoned by the people who were officially in charge.

JOYCE RIVERA: I made an appointment. Put him in my calendar, you know, I mean, how about next Tuesday? Can we meet ? Oh yeah, I'll be here. Okay, great. And then I come and I'd have my car and I said, well get in, we'll grab around, we'll talk.

KAI WRIGHT: Now Joyce knew what she was dealing with.

JOYCE RIVERA: I don't want to tell you that I in any way romanticized this was a man who solved, uh, disagreements with violence.

KAI WRIGHT: But she realized he could help her and they might help the community combat HIV and AIDS.

JOYCE RIVERA: I mean, obviously I hated drug dealers because my brother had just died of HIV/AIDS you know, through drugs. And I was furious around all of that. But I'm teaching him about HIV/AIDS and he wants to know, well, what can I do about it? And of course, I have a ready answer.

KAI WRIGHT: She says, give out free clean syringes. With each heroin sale. No way, he says, he does not want to get that involved. But he has another idea.

JOYCE RIVERA: That I should do it in his spot.

KAI WRIGHT: Cuzón wouldn’t hand out the needles himself, but he’d make a space for Joyce to do it.

JOYCE RIVERA: And he says, no, we'll close up for you. And he did.

KAI WRIGHT: For a couple hours every week, the drug trade stopped. And that same location became what you might call a pop up/DIY public health site.

JOYCE RIVERA: And then he said, you have any business cards? I said, no. He says, make some. We'll give it out with every sale. That's what we did. It said, stay healthy. You know, and it did it in Spanish, you know. Cuida su salud.

KAI WRIGHT: Stay healthy. Cuzón and his team would take Joyce’s business cards and pass them out during drug deals.

JOYCE RIVERA: And they came.

KAI WRIGHT: That first Saturday, in spring of 1990, Joyce drove her hatchback down to the park and unloaded boxes of literature about HIV transmission and boxes and boxes of clean syringes.

JOYCE RIVERA: Hold on, this tree was here, this was a big drug dealing spot.

KAI WRIGHT: She placed them on three tables. And held them down with rocks and bricks from the park. True to his word, Cuzón wasn’t there, but his men were.

JOYCE RIVERA: They unpacked my car and, um, they stood sort of like, you know, sentinels. And it occurred to me that people had to learn to exchange syringes.

KAI WRIGHT: Cause this had never happened before.

JOYCE RIVERA: You know, in a way their sentinels allowed me to create a line that somewhat mimicked the lines that they had for the drug dealing.

KAI WRIGHT: Joyce's DIY needle exchange in partnership with a drug kingpin was a success. In fact, it's so successful, Joyce ran out of those little Red Sharps containers for the used needles. She put out the word: she needed help. And, help came.

JOYCE RIVERA: Then the grandmas came with their bottles of detergent.

KAI WRIGHT: To store the used needles.

JOYCE RIVERA: And then in those lines that they brought me those bottles they talked about their despair about having a daughter that was in jail.

KAI WRIGHT: Needle exchange was still illegal in New York City, and at this point Joyce’s was totally improvising. She cashed out her retirement fund to keep the work afloat.

JOYCE RIVERA: It wasn't a lot of money, but you know, it was like, you know, $15K.

KAI WRIGHT: Soon it wasn't just the grandmothers in line.

JOYCE RIVERA: People came with, you know, evident, uh, HIV, right, and, uh, sickness.

KAI WRIGHT: This time, she found a physician’s assistant from Beth Israel to help people get tested for HIV, which wasn’t so easy back then. When Joyce says she runs a “health hub” now — where you can get lunch, as well as a flu shot — this is where it started.

KAI WRIGHT: But of course, drug dealers are not the most reliable people on earth. Cuzón and his cousin were fighting and eventually Cuzón was charged with hiring someone to murder his cousin. The local police, who had basically been turning a blind eye to this free syringe operation, they told Joyce she had to cut it out; she couldn’t keep operating here.

So now Joyce had a mini-outdoor-public health one-stop shop for drug users with nowhere to put it. She had to find someone to help, and someone told her to turn to, of all things, a local church. A guy named Luis.

ANA GONZALEZ: Oh, there he is.

JOYCE RIVERA: Mi amor!

FATHER LUIS BARRIOS: I'm Father Luis Barrios.

KAI WRIGHT: Even though she never made her first communion, and rarely went to church, Joyce is strategic. She was not afraid to use the church. Father Luis Barrios was the priest of the episcopal church a few blocks up the street. He was already making a name for himself as a bit of a radical.

FATHER LUIS BARRIOS: What I bring to the pulpit is activism. You don't get the community inside the church. You get the church inside the community.

KAI WRIGHT: Father Barrios had seen Joyce at her pop up needle exchange and he could tell she was a powerful person.

FATHER LUIS BARRIOS: I knew all the drug users in the community, but I never saw them in the line and so organized. So she's giving out needles and condoms, and I say, oh, this is very interesting, and then later we talk.

JOYCE RIVERA: And he said, listen, this is what we're gonna do. And he used a word in Spanish: truco. Vamos a hacerte un truco.

KAI WRIGHT: Let's trick 'em. Let's just move this operation up the block to outside of St Ann's because the police, they’re not going to cross onto church grounds.

JOYCE RIVERA: You'll be safe in here.

KAI WRIGHT: Father Barrios isn't just a priest. He teaches psychology and Latin American studies at CUNY. And he was drawn to Joyce, in part because his story was a lot like hers.

FATHER LUIS BARRIOS: With Joycre Rivera, she lost her brother. Uh, with me, I lost three brothers, uh, HIV, AIDS. They were infected in New York City in the South Bronx.

ANA GONZALEZ: Do you know how they contracted it?

FATHER LUIS BARRIOS: Dirty Needles, that was it. We always had the hypothesis, well, it can be sex, can be, but no, they were sharing needles, dirty needles. And then the other three die of overdose.

KAI WRIGHT: Father Barrios gave Joyce an office inside the church building.

FATHER LUIS BARRIOS: This is where your office used to be.

JOYCE RIVERA: Well, there were two desks in here.

KAI WRIGHT: It was a tiny room across from the priest's office,

JOYCE RIVERA: Luis, this was the closet where we kept the syringes.

KAI WRIGHT: Joyce was one of a bunch of activists and community groups.

JOYCE RIVERA: You know, off, off of Broadway theater.

FATHER LUIS BARRIOS: The rainbow office, right? LGBTQ that we created.

JOYCE RIVERA: We had an LGBTQ office. In the midst of all of the sorrow and struggle. This place radiated all this life.

KAI WRIGHT: Father Barrios encouraged a certain ecclesiastical creativity. One time he told her to store the used needles in the crypt below the church.

ANA GONZALEZ: You would bury them?

JOYCE RIVERA: No, we didn’t bury them. We just kept them there until we could find a place to discard them

KAI WRIGHT: Another time he got involved, he knew that if people felt like the needles and condoms were blessed they would be more likely to use them.

FATHER LUIS BARRIOS: I still think that we are the only one who blessed the needles and the condom. And some people came back, asking. So he said, okay, put your hands. Put your hand.

KAI WRIGHT: Father Barrios extends his hands as he remembers the prayer.

FATHER LUIS BARRIOS: We're gonna bless these needles and these condom. And you say, God, the preservation of life, this is what we gonna do. Bless us. And some people really believe.

JOYCE RIVERA: That's his ministry. He reminds everyone that they have God inside them.

FATHER LUIS BARRIOS: Uh, huh.

KAI WRIGHT: So here are two people — who, in the absence of any coherent or effective public health policy, took it upon themselves to fight the virus in their community. Needle exchange finally became legal in New York City in 1992. Joyce was ready to stop improvising. She wrote her first grant. And in 1993 she got it — $70,000. St Ann's Corner of Harm Reduction was born.

JOYCE RIVERA: I was doing harm reduction. Where? At the corner of St. Ann's. Right. And so it became St. Anne's Corner of Harm Reduction.

KAI WRIGHT: Joyce’s work has had real impact. Syringe exchange, combined with the onset of effective treatment for HIV infection, which came in 1996, they dramatically slowed the spread of the virus in the South Bronx. St Ann’s still has a van that parks on corners, offering up free needles.

JOYCE RIVERA: And this is our syringe exchange right now. It’s outside of the park.

KAI WRIGHT: In the early days, the numbers were bad — well more than half of the people they tested had HIV.

JOYCE RIVERA: We had 65% plus of our 250 drug users were HIV-positive.

KAI WRIGHT: So it went from 65 to five.

JOYCE RIVERA: Less than five. It's about three.

KAI WRIGHT: In 2022, in New York City, 1% of new HIV infections were through injection drug use.

KAI WRIGHT: How singular would you say, like, access to clean needles is in that change?

JOYCE RIVERA: Absolutely essential. Pivotal. Pivotal. So we taught people, in effect, a new way of viewing syringes. That you didn't have to pay for them, a new, it was much more profound than we thought going in. We transformed the commodity into a public health intervention. The syringe lost its dollar value. And it became a human endeavor. It has a humanistic value like that. And we didn't know that until we started doing it. The work has made me touch my own humanity in so many ways that it has transformed it, it's made me a better human being. I mean, and yes, I've had loss, but it's never shaken my, um, my faith in humanity.

KAI WRIGHT: Today, Joyce Rivera is turning her focus toward another danger for drug users: the South Bronx is now ground zero in New York City for overdoses. Joyce is trying to open a safe-injection site.

And look, she knows that for thousands of people in the South Bronx, her efforts are not going to be enough. Most households around where St. Ann’s is based have an income of $20,000 or less. And Joyce knows that the problems of poverty can easily lead to addiction.

But Joyce also remembers the lessons she learned with Father Barrios and that drug kingpin: when systems and institutions fail, individuals can still save lives.

So now, if she can keep drug users safe until they can get into recovery, at least she knows she is honoring her brother and making a difference.

Next time on Blindspot: living with HIV today.

KIA LABEIJA: I knew that I was HIV-positive since I was very, very young. Um, and even though I didn't really know what it meant., I knew that I had it.

KAI WRIGHT: Blindspot: The Plague in the Shadows is a co-production of The HISTORY® Channel and WNYC Studios, in collaboration with The Nation Magazine.

Our team includes: Emily Botein, Karen Frillmann, Ana Gonzalez, Sophie Hurwitz, Lizzy Ratner, Christian Reidy and myself, Kai Wright. Our advisors are: Amanda Aronczyk, Howard Gertler, Jenny Lawton, Marianne McCune, Yoruba Richen and Linda Villarosa. Music and sound design by Jared Paul. Additional music by Isaac Jones. Additional engineering by Mike Kutchman.

Our executive producers at The HISTORY® Channel are Jessie Katz, Eli Lehrer and Mike Stiller.

Thanks to Miriam Barnard, Lauren Cooperman, Andy Lanset and Kenya Young.

I’m Kai Wright — you can also find me hosting Notes from America live on public radio stations each Sunday. Or check us out wherever you get your podcasts.

And thanks for listening.

Copyright © 2024 The HISTORY® Channel and New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.