Episode 4: The Massacre

KALALEA: Before we start, I want to let you know that in today’s episode, we’ll talk at length and in detail about the attack on Greenwood. You’ll hear the words of people who were there; who wrote about their experiences or shared them in interviews in the days and years afterwards. So this episode includes descriptions of violence and hatred, including racially offensive language.

[PAUSE]

There’s very few first-hand written accounts of what happened in the days surrounding the massacre. But a few years ago, a group of Tulsans uncovered an amazing document written by a man named B. C. Franklin. It’s a 10-page typed manuscript—when I read it it brought me right back to 1921—to those two horrific days.

We’ve adapted the manuscript for this podcast.

[SOUNDS OF BUSTLING CITY]

FRANKLIN: It is May 31st, 1921. The day is just beginning…. An unbroken stream of pedestrians—male and female—passes down Greenwood Avenue. It is made up of laborers, some empty-handed and others with dinner pails, on their way to work.

KALALEA: Franklin’s a lawyer, who’s new to Tulsa. He’s renting a room in a boarding house while he searches for a home for his young family. He’s looking out the window and sees a group of teenagers. They’re laughing and joking with one another. The sky is clear. It’s the beginning of summer.

FRANKLIN: It is also commencement season and the streets of the city are filled all day long with the happy, innocent, care-free graduates, walking proudly in their caps and gowns. Then comes a lull—a lull before the storm.

[THEME MUSIC]

KALALEA: This is Blindspot: Tulsa Burning. The story of a community set on fire. I’m KalaLea.

Episode 4: The Massacre

FRANKLIN: I had had an unusually hard day of it at court and in my office. By noon, I had finished the trial of a land case. I purchase a newspaper and hurry to my office.

KALALEA: The Tulsa Tribune, a white-owned newspaper, just published a story with the headline: “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator.” It says, a Black boy has been arrested for attempting to assault a white elevator operator. And man, does the news spread fast.

By the late afternoon, large crowds gather outside the courthouse jail in downtown Tulsa—around a thousand white people—men, women and children. They’re rowdy... agitated... and armed.

Some months ago, a white man was forcibly taken from this very same courthouse jail and hanged by another white mob that behaved pretty much like this one.

Some Black folks are convinced that if white people are crazy enough to hang one of their own, they’ll surely do the same... if not worse... to this young Black man, Dick Rowland.

Later that night, a group of Black men arrive at the courthouse. Seventy-five men, many of them veterans, all carrying guns or pistols. Some of the men—white and Black—are full of “choc” beer and whiskey. And they’re ready for a fight.

Then… a gun goes off.

And more shooting.

Pretty soon, the streets of downtown Tulsa start filling up with people. A good number of them are card carrying Klan members but most are regular white people, either from Tulsa or outside the city limits.

They go down to First and Second Streets and break into sporting goods stores, then pawn shops and hardware stores. They’re throwing rocks, shooting out windows, taking anything of value plus what they came for: weapons and ammunition.

The ones with fire power run from street to street shooting at any Black person in sight.

Those lucky enough to have a gun shoot back.

As one witness reported: “The Negroes became the hunted game.”

Across town in Greenwood, B.C. Franklin’s sitting in his boarding room. He can hear the shooting and yelling.

FRANKLIN: I arise, dress, and go to the phone to call the sheriff’s office to find out the trouble. I cannot make connection. I feel puzzled. We would soon be in the midst of a great catastrophe if something is not done at once to avert it. No one can reach the sheriff’s office and no one knows where he is.

KALALEA: I’d like to pause just for a moment. In all my research on Tulsa, people keep talking about the police: where were they ... who was in charge …. And then I read this wild story, which explained so much to me.

That night, Walter Francis White arrives in town. He’s trying to find someone who can tell him what’s happening when he learns that local police are swearing in temporary deputies. They need men to protect downtown from a Black uprising.

But listen to this: Walter White works for the NAACP. He’s a Black man with fair skin and blue eyes, so he can pass for white. He decides he's going to try to sign up.

The officers only ask for three bits of information: his name, age and address, nothing more. He’s asked to repeat these words:

“I solemnly declare I will do my utmost to uphold the laws and constitutions of the United States and the State of Oklahoma.”

And with that, Walter White becomes a deputized officer of the law.

A man standing next to him leans over.

ACTOR: Now you can go out and shoot any Nigger you see, and the law’ll be behind you.

KALALEA: Now there are thousands of armed white men running through the streets of downtown. Many holding a shotgun in one hand and a liquor bottle in another. Cars and trucks drive by, filled with white faces hanging from car windows and shooting at any Black person they see.

FRANKLIN: There is shooting now in every direction. And the sounds that come from the thousands and thousands of guns is deafening.

KALALEA: Black people run as fast as they can away from the white mob—back home to safety, to Greenwood. Black military vets set themselves up in strategic locations, using techniques they’d learned during the war in Europe. One group fires back at the gangs of white people attempting to cross the tracks into the neighborhood. Other men shoot from behind the Frisco train station, or from tall buildings.

FRANKLIN: I see the top of Stand-pipe Hill literally lit up by the blazes from the throats of machine guns, and I can hear bullets whizzing and cutting the air.

KALALEA: On top of the hill a different group of Black men have posted up. They’re shooting at dozens of National Guard soldiers and any other deputized white person trying to invade Greenwood. But real fast, it becomes clear they’re outnumbered.

B.C. Franklin is still holed up in his room. He paces around and watches the battle from his balcony. The main fight hasn’t reached the interior of Greenwood. It’s only on the fringes.

And then, around 2am, Greenwood gets quiet.

The sound of gunshots are distant and few. The men fighting for their community are like, we did it, we kept the white folks out of Greenwood, and Dick Rowland is still alive.

Franklin breathes a sigh of relief. But he doesn't sleep. He stands on the balcony, thinking and watching.

FRANKLIN: When the eastern sky reddens, announcing the approach of the day, I walk from the front porch into the bathroom and wash my face. I leave the building for my office.

KALALEA: It’s 5am.

FRANKLIN: As I reach the sidewalk a shrill whistle sounds from the direction of Standpipe Hill.

[WHISTLE]

KALALEA: No matter where you are in Tulsa, you can hear it.

FRANKLIN: And then, immediately thereafter, the sound of 5000 feet, it seems, descends that Hill in my direction

KALALEA: It’s actually more than double that. Thousands of armed white people come running over the train tracks, spilling out from behind the boxcars and stations, screaming, all heading in the direction of Greenwood.

Some of the Black vets are still awake—ready and waiting for them.

Franklin doesn't have time to wait, he darts through vacant lots and behind empty buildings—trying to find a way out.

Shots echo all around him, and smoke fills the air. That’s when he sees a familiar face—John Ross, the young soldier. Franklin had last seen Ross a just couple of years before, when Franklin gave a speech, encouraging young Black men to enlist in the war.

[TONAL CHANGE]

This an encounter that would haunt Franklin in the years to come. Two men, who once had such faith in America, now unarmed, running for their lives.

FRANKLIN: “I asked him … Ross—where have you been and where are you going?”

He told me, “I was out of the state until this morning. I had a feeling, a bad one, then came running home to find this. It’s a miracle that I got through the mountain of white men on the other side of the city. Franklin, we’re literally surrounded.

I'm going back home to defend it or die in the attempt.”

[BEAT]

When young Ross leaves me, I think of those stirring words of President Wilson, “We must fight to make the world safe for democracy.” I repeat those words aloud and they sound like hollow-mockery. I think too of that other saying found in the scriptures, “He saved others; but himself he cannot save.” That saying seems so applicable to my race. We have saved others any number of times. We have saved, or helped mightily to save, this nation from the enemy upon countless battle fields. And now, young Ross and I and the whole race are unable to save ourselves.

[TONAL CHANGE]

FRANKLIN cont’d: I reach my offices in safety. But I know that that safety is short lived. I now know the mob spirit. I know that it cares nothing about the written law and the constitution.

KALALEA: He hears a buzzing sound from up above.

FRANKLIN: From my office window, I can see planes circling in midair. They grow in number. I can hear something like hail falling upon the top of my office building.

Flames roar and belch and lick their forked tongues in the air. Smoke ascends the sky in thick, black volumes. The planes, now a dozen or more in number, hum and dart here and there. The sidewalks are literally covered with burning turpentine balls. Every burning building first catches fire from the top.

‘Where oh where is our splendid fire department with its half dozen stations?’ I ask myself. ‘Is the city in conspiracy with the mob?’”

KALALEA: Tulsa’s fire department tries to get to Greenwood. But white attackers threaten to shoot them if they help put out the flames.

And the men behind these threats aren't hiding their identities. Some are wearing their police uniforms while they set fire to homes.

Franklin is moving as quickly as possible. Making his way towards the outskirts of Greenwood. But it’s even more dangerous there. There’s a machine gun sitting on top of a grain elevator, aimed at Greenwood.

Franklin sees a woman flying across the street. She’s trying to grab hold of her child who is running away from her. Bullets fly past.

FRANKLIN: I shout out “Turn back woman. For God sake, turn back! You will be mowed down!”

Never turning her head, she answered as she hurried on, I must follow my child. And so she follows her child and not a bullet touches her although they literally rain down on the street.

KALALEA: Across from Franklin, on the corner, another building goes up in flames. A woman, a child, and three men come running out of it.

FRANKLIN: The three men, one lugging a heavy trunk on his shoulder, are all killed as they cross the street. When the old man is hit, no doubt by a dozen bullets, he falls sprawling. Blood runs down the street. I turn my head from the scene.

Across the street, directly in front of me, stands the Gurley building, property of a very wealthy and up to that time a very influential colored man. I hear shots fired from behind that building and hear angry and profane voices saying, “Come out of there Gurley, you Black son of a bitch.”

KALALEA: Franklin doesn’t stick around to see what happens next. He keeps running through the neighborhood, heading back to his rooming house. He needs a gun.

Minutes later, he looks up and realizes he’s standing in front of the Ross’ residence, where the young soldier lives. Ross’ roof is on fire and it’s spreading. A group of white men are heading in his direction.

Then, Franklin hears the young soldier. He’s in an upstairs window. Ross has got a rifle and he’s shooting down at the attackers.

It seems like a losing battle, but the feeling Franklin has in this moment is pride.

FRANKLIN: I, somehow, feel happy. I can not explain that feeling. I never felt that way, before nor since.

KALALEA: And then…. Franklin turns around and finds himself face to face with the mob.

FRANKLIN: Directly in front of me stands a thousand boys, it seems, with guns pointed at my head. They command me to “right about face.” Then one half-starved ruffian comes forward to search me. Finding no weapon, he starts to take my money.

KALALEA: He surrenders, and reluctantly follows the armed white men.

Soldiers in Oklahoma’s National Guard stand next to civilian members of the white mob as they round up Black people and march them north. They’re taking them to an internment camp set up at the edge of Greenwood.

By the day after the massacre, June 2nd, some six-thousand people—all of them Black—have been forced to go to make-shift detention centers. They’ve just witnessed their homes being robbed and set on fire. They’re exhausted, hungry, angry and in shock. And most of them no longer have a home to return to.

FRANKLIN: The people are fed and watered like so many cattle by the benefactors who had allowed the mob to take their government away from them and trampled their laws and constitution under their unhallowed and barbarous feet.

KALALEA: Franklin, whose grandfather bought his whole family’s freedom from slavery. Franklin—a man who was educated, a man who built his life and career in service of the law—now finds himself with no home, no money, living in a tent. Everything else—gone up in smoke.

FRANKLIN: During that bloody day, I lived a thousand years. I lived the whole experiences of the race; the experiences of Royal ancestry beyond the sea, experiences of the slave ships on their first voyage to America with their human cargo, experiences of American slavery and its constant evils, experiences of loyalty and devotion of the race to this nation and its flag and more and in peace, and I thought of Ross yonder, out yonder, in his last stand, no doubt.

[ANOTHER VOICE COMES IN]

JOHN W. FRANKLIN [reading]: I thought of the place the preachers called hell and wondered seriously if there was such a mystical place, it appeared, in the surrounding, that the only hell was the hell on this earth, such as the race was then passing through.

[PAUSE]

JOHN W. FRANKLIN cont’d: My name is John Whittington Franklin. I'm the grandson of attorney BC Franklin.

KALALEA: More from John W. Franklin—in a minute. This is Blindspot.

[[MIDROLL]]

KALALEA: This is Blindspot: Tulsa Burning. I’m KalaLea.

John W. Franklin was sixty-five years old when he first read his grandfather’s manuscript. At that time, he was a manager at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

KALALEA: Do you remember, like when you first read his manuscript, what was your reaction that first time?

JOHN W. FRANKLIN: When I read it, it's a very powerful piece. And I wept.

KALALEA: The manuscript was found in 2015, in a storage vault in Tulsa. Back in D.C., John W read it three times and cried every one of them.

JOHN W. FRANKLIN: You hear in World War One about people who have been traumatized by the war, but you don't hear what that called for people who have trauma in a domestic setting. And I think that Tulsa, and the impact of the massacre on the people who survived, was tremendous. They lost their personal belongings. They lost their friends, their loved ones. When you have a catastrophe, it creates an exodus and people leave a place of a catastrophe, some of them never to return.

KALALEA: We know that your grandfather was in Tulsa alone and was looking for a home for his wife and children. And so I could imagine his wife, your grandmother, was really worried. What happened to her?

JOHN W. FRANKLIN: So my grandmother learns of the massacre and does not know if her husband has survived until he sends word, I guess a note, that he has been detained in the convention hall for several days, that he's unharmed, but he has no place to receive them.

KALALEA: Was his rooming house, the place where he was staying, was that destroyed as well?

JOHN W. FRANKLIN: Yes, And so what personal effects he had, what money he had saved, went up in smoke.

KALALEA: Mm. Your grandfather died in 1957. Did you get a chance to get to know him?

JOHN W. FRANKLIN: Yes. Until I was eight. He died when I was eight.

KALALEA: Until you were eight.

JOHN W. FRANKLIN: He came and saw me as soon as I was born, both grandfathers came to Washington, and I go to Tulsa for the first time when I'm two. I have a picture of my grandfather holding me and my toy cat at two in Tulsa.

KALALEA: And what was he like? Like, what do you remember about him or how do other people describe him to you? Other family members?

JOHN W. FRANKLIN: Well for everyone, he was attorney B.C. Franklin, and he was highly respected. He was a judge by that time. I remember him as very serious. I have a picture of him smiling, and it's the only time I can recall him smiling is in a picture of him smiling.

[PHONE RINGS IN THE BACKGROUND]

KALALEA: Can I ask, is that your phone ringing?

JOHN W. FRANKLIN: It is.

KALALEA: It’s a house phone?

JOHN W. FRANKLIN: It is. We’ve paused that phone, it will not ring again.

[PAUSE AND MUSIC]

KALALEA: Can we talk about your grandfather’s experience during the massacre? What did you know about that? Did he ever talk about it and its effect on him?

JOHN W. FRANKLIN: He didn't discuss it with me. I grew up knowing about the massacre from my father. My father, he was six years old, and from the age of six to 10, they are a separated family. And they're not able to live together as a family until 1924.

KALALEA: That’s because your grandfather was helping a lot of the survivors and victims of the massacre?

JOHN W. FRANKLIN: Yes. Immediately following the massacre, with his law partner and their temporary secretary, they're processing insurance claims from homeowners and businesses that were destroyed in the massacre.

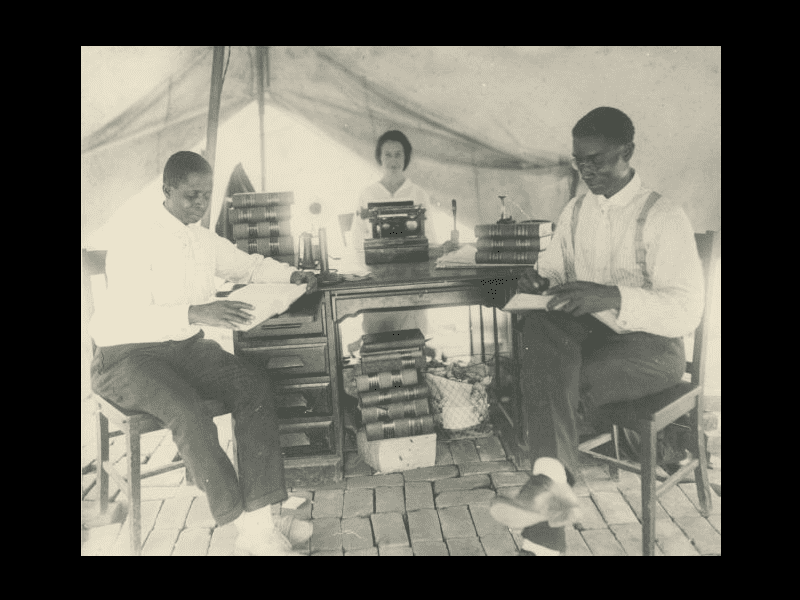

KALALEA: There's a photograph of your grandfather that I really love. It's of him sitting in a tent. And he's working and there's a typist or a stenographer or something like that.

JOHN W. FRANKLIN: It's a sepia-colored photograph of a red cross cloth tent. There's a brick floor. There's a desk, which Ms. Thompson is sitting at with a typewriter and between the typewriter and I. H. Spears is a telephone. Telephone is in two parts. There's a part that you put on the table, and there's a part that you take and listen to in your ear.

Very different from the phones we have now. But I think it's remarkable that in a red cross tent following a catastrophe, six days later, they have a phone in their tent.

KALALEA: Right how did that happen?

JOHN W. FRANKLIN: Yeah, remarkable. I don’t know.

KALALEA: B.C. Franklin worked out of that tent every day, trying to get insurance companies to pay out claims to the people of Greenwood.

JOHN W. FRANKLIN: At the same time, the city council has passed an ordinance saying that African-Americans could only rebuild with non-flammable materials, which were harder to come by and more expensive of course. And then he successfully fights that to the state Supreme court.

KALALEA: The road to rebuilding was long. In the days after the massacre, about half of Greenwood’s residents left. And for those who stayed, like this young woman, the violations were far from over.

PARRISH: People were seen to flee from their burning homes, some with babes in their arms and leading crying and excited children by the hand. I walked as one in a horrible dream.

KALALEA: Mary Elizabeth Jones Parrish was a journalist living in Tulsa when the massacre happened. She fled for her life with her young daughter, but returned to Greenwood a couple days later.

Parrish writes about a moment when she was riding in the back of a truck operated by the Red Cross. They were heading back into town. But first, she had to pass through the white section of Tulsa:

PARRISH: Dear reader, can you imagine the humiliation of coming in like that? With many doors thrown open watching you pass, some with pity and others with a smile?

Soon we reached the district which was so beautiful and prosperous-looking when we left. This we found to be piles of bricks, ashes, and twisted iron, representing years of toil and savings.

For blocks we bowed our heads in silent grief and tried to blot out the frightful scenes that were ahead of us.

KALALEA: Parrish wrote a book about the days and weeks immediately following the massacre. She catalogued the losses of buildings, property, and people. While at the same time, reporting on the efforts to rebuild.

BRUNER: My great grandmother she stayed. She said, I want to see this thing through. My name is Anneliese Bruner, and I am the great-granddaughter of Mary Elizabeth Jones Parrish.

KALALEA: When did you first learn about your great-grandmother’s book?

BRUNER: I went home over the holiday break, ‘93, ‘94. My dad took me aside and he took me into his room and closed the door. I knew at that point that it was something serious. I was worried, oh, maybe it's a health issue. But he said, I have something to give you. He went over to his papers and he pulled out this little red book. A small and very slim volume. It didn't look like any book I had really ever seen before. It was worn around the edges and it was cloth bound. On the front of it, it had gold lettering. Events of the Tulsa Disaster by Mrs. Mary E. Jones Parrish. And he said, Lisa you're the matriarch of the family now, and I want you to see if there's something that you can do with it.

At that time I was 34 years old. I sat down, read through the book. I was stunned for any number of reasons, as you can imagine: the content, the stories that poured out of this volume of human suffering, human brutality, human resilience.

But also I was shocked. My father had never said a word about this to me.

KALALEA: So, you receiving that book is the same time you learned about the massacre? Or had you heard about it before?

BRUNER: KalaLea. It was all simultaneously. The book, the massacre, my family's connection to it, my great-grandmother's work. All of this came down on me at one time. I had no clue of any of this. No inkling, no whisperings, no indication that there was some big family secret, nothing, zero.

KALALEA: What did that feel like for you, to get all of this information just like dropped on you in one day, you know, in one moment. What did that feel like?

BRUNER: It felt like a mix of feelings. One of them is betrayal. How could my family not have shared this with me? But that's a self-focused response, of course. But then as I began to think more broadly, I began to have more compassion for what that must've felt like in terms of how my grandmother, as a young child of seven, lived through such a horrific event. I mean, what an experience for anyone, but particularly for a young girl to have to endure and carry forever for the rest of their life.

So I understand the complexities of motivations that people have for doing or not doing any number of things. So I have great compassion for my grandmother and what she endured and why she may not have wanted to talk about it.

KALALEA: I would imagine that some things came into focus for you. You know, there's things about your family members, you learn later in life, they might've passed, and then it dawns on you. So I'm just wondering for you, did you have like, kind of a revelation or a moment of like, no wonder.

BRUNER: Well, my grandmother self-medicated with alcohol. And so, um, I knew that there were issues. And, it wasn't really until I was in college that I understood, even that my grandmother had alcoholism. My father also developed alcoholism. They had a lot of family trauma, and certainly these things are passed down from generation to generation. People think it means, you know, we're talking about genetics here. Depression yes has a genetic component. But some of these are just behaviors that arise because of the chaos that is passed down from generation to generation. And the responses and the symptoms are just the outward manifestation of the suffering that people are enduring and carrying around with no hope for resolution.

KALALEA: In the book, her great grandmother Mary Elizabeth Jones Parrish interviewed dozens of survivors. Her report was the first published book to include eyewitness accounts of what took place during and after the massacre.

BRUNER: They exhibited that spirit of self-sufficiency and cooperation that drew my great-grandmother to Tulsa in the first place. So it was a wonderful place. It wasn't a perfect place, but it was a wonderful place.

KALALEA: There’s a passage from your great grandmother’s book that stood out to me when I read it, near the end of the introduction. And it’s a warning of sorts.

PARRISH: Just as this horde of evil men swept down on the Colored section of Tulsa, reducing the accumulation of years of toil and sacrifice. If something is not done to bring about justice and to punish them, thereby checking that spirit, just so will they, some future day, sweep down on the homes and business places of their own race. This spirit of destruction, like that of mob violence when it is once kindled, has no measure or bounds. Neither has it any respect of place, person, or color.

KALALEA: (sigh) Man. What do you think your great grandmother is saying, and why does it matter now?

BRUNER: It is an inspirational and cautionary paragraph. It tells us that when people are not punished for wrongdoing, they won't stop themselves. That passage connected to a recent event: 1/6, the Capitol insurrection, where our democracy itself was on the line. These people were animated by hatred, lies that had them believing that they had been somehow robbed. Their grievance was high and their boundaries were low. The spirit of mob violence had been kindled within their hearts by the outgoing president at the time.

And we saw what they did. These people were willing to seize what they wanted by violence and power. And they feel justified. That's the danger here. And you know, that provides a moral void, a moral vacuum where these kinds of things continue to flourish without a clear moral direction and a moral consequence to this type of behavior.

KALALEA: Hm.

BRUNER: This is a serious threat, and Mary Jones Parrish says the nation must awake.

KALALEA: Tulsa's mayor had publicly said, you know, that he does not think that reparations are tenable. In a recent interview for NPR, he said:

BYNUM: The idea of financially penalizing this generation of Tulsans for something criminals did 100 years ago; that's a hard thing to ask.

KALALEA: What is your reaction to that?

BRUNER: Is that penalizing them or is that giving them an opportunity to participate in the restoration of justice? It depends on how you look at it. I suggest a reframing. And it would invite people to think about this, not as punishment for someone else, for what someone else did, but for an opportunity to contribute, to healing, to people who deserve it.

KALALEA: Mr. Franklin, I want to ask a question about the Tulsa mayor, who publicly says that he doesn't think that reparations are tenable. What do you say to that? What is your reaction to that?

JOHN W. FRANKLIN: You're so quick to say, we don't have the money to do this. Sorry. That's an easy excuse. But it doesn't look to the causes. It doesn't look to the people who are responsible, does not even seeking to find out who was responsible for this. The mayor's great grandfather was mayor in 1899 on his father's side. And I want to know what was his family doing in 1921? I know where my family was. I know exactly where they lived. I know what they did. Where were your family members? What were your family members doing?

Part of the challenge that Tulsa faced and faces is that we know the names of many of the victims of the massacre. But we have no names of the, or faces, of the perpetrators of the massacre. And so…

KALALEA: It's a good question.

JOHN W. FRANKLIN: ...to have reconciliation, you need two sides. You can't have a one-sided conversation that leads to reconciliation. And so part of Tulsa is in denial. They have been in active denial that they could have done this to a community. So we're going to have to continue to tell this story.

[MUSIC COMES UP]

KALALEA: B.C. Franklin’s story of the massacre doesn’t end in the days after. He wrote a postscript. In it, he describes a visit 10 years later to the soldier John Ross—the one he heard shooting at the white mob from a window of his home. Turns out, he survived.

FRANKLIN: A little more than 10 years have passed. Young Ross, the veteran of the World War, survived the great catastrophe, but lost both his mind and eye sight in the fire that destroyed his home. With a burned and scarred face and a mindless mind, he sits today in the asylum of this state and stares blankly into space. Young Mrs. Ross is working and doing the best she can to carry on in the times of Depression. She divides her visits between her mother-in-law and her husband at the asylum. Of course, he has not the slightest recollection of her or of his mother. All yesteryears are only blank pieces of paper to him. He could not remember one thing in this living, breathing, throbbing present.

[PAUSE]

KALALEA: What happens to the physical body when it endures such an assault, or experiences such a tragic event? And is it ever possible to truly heal?

[THEME MUSIC]

That’s next time, on Blindspot.

Blindspot: Tulsa Burning is a co-production of The History Channel and WNYC Studios, in collaboration with KOSU and Focus Black Oklahoma.

Our team includes Caroline Lester, Alana Casanova-Burgess, Joe Plourde, Emily Mann, Jenny Lawton, Emily Botein, Quraysh Ali Lansana, Bracken Klar, Rachel Hubbard, Anakwa Dwamena, Jami Floyd, and Cheryl Devall. The music is by Hannis Brown, Am’re Ford, and Isaac Jones.

Our executive producers at The History Channel are Eli Lehrer and Jessie Katz. Raven Majia Williams is a consulting producer. Special thanks to Alex Barron, Wilder Barron, Danny Wolohan, Shelley Miller, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, Trinity University Press, Jennifer Lazo, Andrew Golis, and Celia Muller.

Andre Holland was the voice of B.C. Franklin; and Jordan Boatman was Mary Elizabeth Jones Parrish.

I’m KalaLea, thank you for listening.

###