What's Gone Wrong For the Rikers Island Federal Monitor

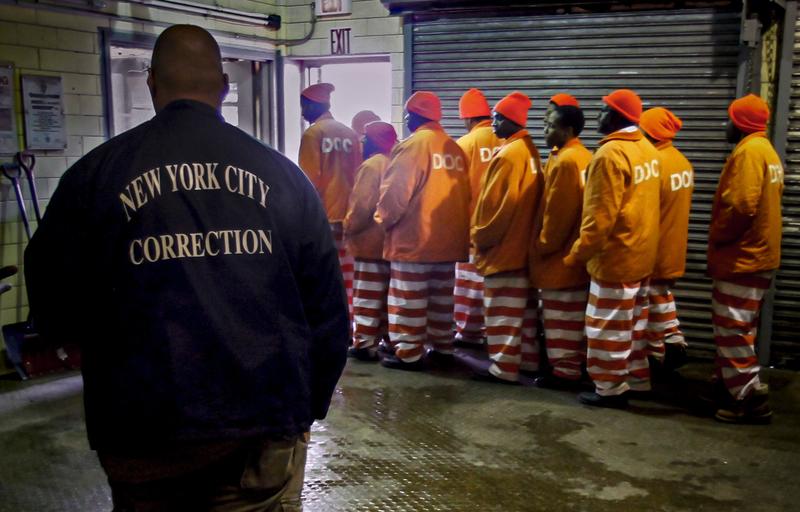

( Bebeto Matthews / AP Photo )

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. If you were listening on Monday, you heard us cover the rising death toll of inmates. Just one aspect of what is being called a humanitarian crisis at Rikers Island. This year, 18 inmates have died in New York City jails or right after their release, making it the deadliest year since 2013 when there were many more people incarcerated at Rikers. In case you missed it, here's a clip from our interview with Lezandre Khadu, mother of Stephan Khadu, who died from meningitis while in custody at Rikers last year.

Lezandre Khadu: The things that my son had to indulge in there was not fair, and it was not cool for anyone to have to suffer like that. No one should be put in that place where lives are being taken away every second, every day.

Brian Lehrer: New York City officials are now looking for ways to get the crisis under control. A big one took a step in court yesterday or did it? A little more background and his appearance on this show last month, Comptroller Brad Lander called for the appointment of a federal receiver taking Rikers Island out of the city's control altogether. Here's his reasoning.

Comptroller Brad Lander: A receiver has the power to move past, to cut through some of the managerial issues, some of the procurement issues. Again, it's not a magic fix but I think at this moment of full scale emergency, it's necessary to get the violence under control.

Brian Lehrer: A federal judge held a hearing yesterday on the appointment of the federal receiver. With us now to discuss the outcome of the hearing and more about his reporting on Rikers is WNYC Public Safety correspondent Matt Katz. We will also touch on an emerging story from his hometown of Philadelphia where there's an attempt to remove the famous progressive DA. Hey Matt. Welcome back to the show.

Matt Katz: Thanks, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: What did the federal judge decide in yesterday's hearing on the appointment of the federal receiver, and how did they reach their decision?

Matt Katz: No receiver. This is Judge Laura Taylor Swain. She heard arguments from the Legal Aid Society, which represents detainees at Rikers, and filed this class action suit back in 2011 saying that there were constitutional violations at Rikers. That suit ended in a consent decree, which is why the federal judge is involved in this case. The federal judge had appointed a monitor seven years ago to oversee Rikers, and finally the Legal Aid Society this year said, "Listen, it's not enough." In every way imaginable Rikers is more dangerous than it was back in 2011 and 2015 when this consent decree began.

They said yesterday in court, "Listen, we need a receiver. We need somebody to come in and literally strip control of the jails away from the city. Break city laws that are holding back progress, break union contracts like unlimited sick leave for correction officers," which some say is a reason for a lot of the absences and therefore a lot of the problems at Rikers, because there's just not enough staff there. They were arguing for a new aggressive federal intervention and the judge disagreed. She was swayed by arguments made by the correction commissioner Louis Molina, who was appointed by Mayor Adams less than a year ago, and by city attorneys, that progress is starting to take hold there. That there's a glimmer of hope that things are turning around at Rikers.

The US Attorney's office in the southern district, Damian Williams's office, is also a party to this suit, and he also decided not to support a receiver. They basically stayed out of it. They said, "We'll reserve a judgment for a later date, but we're not supporting a receiver at this time." There's not a hearing in this case until well into next year. It looks like, at least for the foreseeable future, this dream that a lot of activists for incarcerated people had, a lot of council members had, Brad Lander, the city comptroller was also pushing for this. That dream of a federal receiver is not going to happen anytime soon.

The jails at Rikers will remain under the control of Adams and his administration, and people are just going to hope things get better there, but there is no question things are worse than they have been in many, many years by almost every measure that you look at.

Brian Lehrer: From the reporting that you released yesterday on the progress or whatever the opposite of progress is since a federal monitor arrived a number of years ago, that's somebody from the federal government to oversee it without it going fully into federal receivership and taking control away from the city. Since that federal monitor arrived, you wrote, the rate of fights and assaults per detainee has nearly doubled. According to annual reports from the mayor's office, a person in custody is seven times more likely to be seriously injured by another detainee.

Staff are almost twice as likely to be assaulted, and slashings and stabbings have increased each of the last four years. That's on top of this completely unacceptable and rising death rate at Rikers, which has peaked with 18 deaths already this year, and the year isn't over yet. Matt, I'm astonished that the judge came to the conclusion that progress is being made. How did she come to that conclusion?

Matt Katz: I was astonished as well. This is the judge who has been on the case from 2015. She appointed, as you said, this federal monitor, and if I could talk about him for a moment. He was a correction expert. He testified in trials. He would come in and consult on jail systems to help them fix the place. He was hired by the federal government in 2015, by this judge essentially, to deal specifically with violence and use of force, which are two areas that have gotten far worse since he got there. Even though he was essentially hired by the federal government, he's paid for by you, he's paid for by city taxpayers.

It took us a while, but we dug into the records. We finally found out how much he's been paid by the city, and this came from the city law department. He has a team of eight people, this monitoring team, and they've made $18 million over the last seven years. That's at least $18 million because there's also this compliance unit within the correction department that it supplies them information. There are employees within the correction department that are also paid because of this monitorship. His team has made $18 million. He personally collects more than $400,000 a year and works an average of 23 hours a week.

He makes more than the mayor and works a part-time job. What we found in this story, we published yesterday on Gothamist and I spoke to Michael Hill on Morning Edition about it too, is that he has not had any success in turning the system around. In his most recent report, rated the correction department as non-compliant in most of the areas that he's been judging them on over the last several years. Yesterday in court when it came time for the judge to say, "The monitor is not enough. We need something stronger, we need a receiver, we need somebody to take it over."

She listened to arguments from the city, from the correction commissioner, Louis Molina, that he just got here in January, and that there were small signs like violence going down in one particular jail at Rikers, the hiring of 28 new civilian leaders because there's been an issue with lack of management and not having leaders from outside the department. They have too many who have come up through the ranks. That's long been a criticism. This new hiring of leaders, this new correction commissioner who the judge seems quite impressed by, she indicated that that shows signs of a glimmer of hope and that a receiver is an extraordinary intervention, and that's not something she's going to entertain at this time.

There was a family in the courtroom yesterday, in federal court, who just lost one of their loved ones at Rikers through an apparent suicide just a few weeks ago, and they sat in the front row and she wished, the judge, Judge Swain wished that family her condolences. She said she hopes that other families don't have to go through the same thing, but Brian, there have been 18 deaths this year, mostly because of drugs that are getting into the facility somehow. Drugs and suicide. The suicides happen when often there aren't officers available or doing the work that they're supposed to do to check on people and to make their rounds.

There's an extraordinary spike in deaths that the Board of Correction Oversight Body that advocates link directly to problems with management and running the facility. That connection and a need to do something more aggressive about it was not made yesterday in court.

Brian Lehrer: We're getting an interesting-looking call, not about Rikers Island per se, but Jonathan in Macintosh County, Georgia, I think is calling to say that he had his first experience being put in jail last night. Jonathan, you're on WNYC. Hello from New York.

Jonathan: Hey, Brian. Hello from McIntosh County, Georgia.

Brian Lehrer: How'd you find our show, and what story do you want to tell us?

Jonathan: WNYC is probably one of, if not the best NPR stations that exist in this country. I listen to KPCC out of LA, KQED, but WNYC, and your show in particular, it's the best and everyone around the nation should know about it.

Brian Lehrer: That's very kind. What happened to you?

Jonathan: What I wanted to speak about is that, what I'm realizing in my adult life, a lifelong supporter of prison reform and rehabilitation and not just penalization, it's easy to talk about statistics. It's easy, as tough as it is, to hear about conditions and experiences from other people within the prison system and going to jail. I didn't really understand until I went in last night. I would like to say that there is no doubt in my mind that the whole system is set up to make it incredibly uncomfortable, including for the staff. It's not a surprise that there's staffs at Rikers who are just not showing up to work.

It's even less of a surprise that there are people who are being neglected intentionally so that they do suffer the worst experience, including death. It's just you don't know until you're actually in there, and I don't mean to sound naive. It did happen to be the first time that I was arrested.

Brian Lehrer: Do you want to describe it a little bit? You don't have to tell us what you got in for if you don't want, but there was something about the experience that obviously was surprising to you, even as somebody who says you were already interested in jail and prison reform. What was it?

Jonathan: The biggest that I experienced was that from the get go, from the arrest, there was seemingly intentionally provided misinformation, including about my personal rights during the arrest. Then upon getting processed at the jail, anything from the proper address and telephone number of the the tow truck company that had my car to just the information about how to make phone calls. There was a lot of information that easily could have been explained upfront as well as throughout the experience, but just wasn't. It made it so that I was put in a position to navigate basically the social ins and outs of being incarcerated in a cell, trying to ask people information.

As we all know, from TV, you don't want to ask too many questions, you don't want to reveal too much about yourself, you don't want to come off as weak. All those things are real in jail, and there are people with white supremacy tattoos, and yes, it's real. You got to deal with that, and no one is there to help you, and the information is such a huge component about having to navigate the entire experience. They want to keep you down. No windows, no clocks. I've never found myself in any point in my life doing this, but I just wanted to sleep it away. The only thing I could do is just sleep. Fluorescent lighting, overly cold. This doesn't make sense. We're in Georgia. It's a little bit cold down here, but it was ridiculously cold in there. No blankets, and-

Brian Lehrer: No blanket?

Jonathan: -ironically a TV that's blaring advertising from the outside world. It just makes you feel incredibly frustrated and I can understand why someone would commit suicide.

Brian Lehrer: Jonathan, thank you very much for checking in. We really appreciate you sharing your experience,, troubling as it was, from McIntosh County, Georgia. McIntosh County, by the way, is like southern coastal Georgia near the Florida border down there, and no, I didn't know that. My producer looked it up. This is WNYC FM HDNAM New York, WNJT FM 88.1 Trenton, WNJP 88.5 Sussex, WNJY 89.3 Netcong, and WNJO 90.3 Toms River.

We are New York and New Jersey public radio and live streaming at wnyc.org. A few more minutes with our public safety correspondent, Matt Katz, as we talk about a federal judge's decision yesterday not to put Rikers Island into federal receivership, and we're going to get to the impeachment attempt. I guess he was impeached actually, but may or may not be removed from office, impeaching the famous progressive prosecutor in Philadelphia. Matt, that was quite a call. Though his experience was far from Rikers Island, did you hear echoes? Did you hear connections that you can make to your own reporting?

Matt Katz One thing that people who aren't necessarily familiar with the criminal justice system should remember is that Rikers Island, the jail that this gentleman was at, they're pre-trial detention centers. The vast majority of the people at Rikers are just accused of a crime, they have not been convicted, and they're waiting on their hearings. They're waiting on this whole justice system that's happening outside of their jail cell to let them know when it's time to come to court, and to maybe pursue a trial, or get into settlement talks and all the rest. Where they stay is not meant for long term stays, and yet they don't have the same access to programming that people in, let's say, a prison might who are sentenced to be in there for 5 to 10 years.

When they're in an intake facility at Rikers, we know that they sometimes don't have access to bathrooms. We published photos a month or two ago of a man who ended up defecating in his pants because apparently he didn't have access to a bathroom when he first arrived at Rikers, and ended up in this intake facility for longer than he was supposed to. They're crowded in these intake facilities. The jails can't necessarily handle all the people that come in at one particular time. The other thing he said that's reflective, he was talking about how he could see how someone might want to commit suicide.

The correction officials at Rikers tell me the issues that they're having in terms of suicides and drug overdoses are reflective of what's happening in jails across the country. There have been other jail systems that are also seeing record high levels of death. This is clearly an American issue. Then the final thing I'll say, correction officers have an incredibly difficult job. They face a ton of abuse also from detainees. That is also a national issue, and I'll say, since this monitor came to Rikers, I'll bring it back to Rikers for a moment, the number of attacks on staff have also increased. It's actually less safe for staffers at Rikers than it used to be.

Staff are almost twice as likely to be assaulted now than they were back in 2015 when the Federal Monitor first got involved in this case. The issues at Rikers are really reflective of a larger national criminal justice problems.

Brian Lehrer: With this Federal Monitor in place, who was supposed to make things better, and all the ways that you've documented it becoming worse with the annual cost of incarceration growing to more than half a million dollars per person per year, plus the $18 million that New York City taxpayers have paid to the Federal Monitor. You spoke with Vince Schiraldi, the former commissioner of the Department of Corrections under Mayor de Blasio, and known as a reformer. Here is what he had to say about the federal monitorship.

Vincent Schiraldi: The question is, does this cost the city a lot of money beyond just the monitor and this team's salary? The answer is yes, and it's not successful. It's not so bad if it costs money and it works, but so far it doesn't.

Brian Lehrer: You reported in a groundbreaking story that you did on revealing images of inmates locked in caged showers, defecating in their pants due to lack of bathroom access, other horrors. How is it, Matt, that such massive dysfunction could be so expensive?

Matt Katz: Part of the reason, people say is because of the nature of Rikers. That it's this unwieldy facility that is out of date, that has broken down. It can take 15 minutes just for a group of officers to bring somebody to the infirmary because of the extent of the place, the mass of the place and the complicated ways to get around. It's also there's the monitorship. You have a team of people that have sometimes been a dozen large just for the compliance unit to supply information to the monitor. When Vinny Schiraldi, the former correction commissioner just now was talking about the cost of the monitorship beyond the $18 million, it's because of the salaries of those employees.

There is just inefficiency after inefficiency baked into the system. That's why there's this plan to close Rikers by 2027, which supposedly is going to save the city a ton of money. The problem though, is we have almost 6,000 People now held at Rikers and in order to close Rikers and move people to these four borough based jails that they're currently building, the population needs to be a lot smaller, it needs to be like 3,300 people. The cost of this criminal justice system, the 500,000 plus per detainee, is really reflective in just the incarceration mentality to begin with, the fact that we incarcerate people at such a high extent and do so more than most of the rest of the world. That's really what costs so much money and that's why people of all stripes are saying, "Listen, if you want to fix the safety issues of Rikers, if you want to be able to close it down and move people to more humane facilities, you got to decarcerate." That requires a mayor who's on board, an entire justice system that's on board, and we're not really there yet.

Brian Lehrer: Here's Miroslav, a retired New York City police officer calling from Ulster County. Hi, Miroslav. You're on WNYC. Hello.

Miroslav: Good morning. Pleasure to talk to you. I was telling your screener that, based on my experience as a police officer in Manhattan, central booking, Brooklyn central booking and I've seen some prisons down in Texas also years ago. Given a choice, based on my experience of being a correction officer or being homeless, I would take being homeless. I know that sounds extreme, but being locked in four walls, and everyone hates each other, everyone is angry. Obviously, nobody wants to be there. It's just a horrible place. They seem to be run on some 18th or 19th century principles.

Brian Lehrer: Have you seen in your experience any model of prison where it's done as well as it could be done?

Miroslav: Not personally, but I have watched other shows, documentaries on the European prison system and some progressive prisons in this country, I believe there was one in California, where they just have basically redesigned the whole concept to give people a little privacy but safety. One of your previous callers, the gentleman that was just incarcerated, said there's no clocks. ell depriving a prisoner of time references is just an old school way of basically dehumanizing them.

Brian Lehrer: Psychological torture.

Miroslav: Right, exactly, and so many other things that go into it. Don't get me started on private prisons, because that's the worst idea.

Brian Lehrer: Miroslav, thank you for that disturbing but revealing portrait of what a former police officer within the system. Thanks. Matt, we just have a few minutes left and I do want to switch gears and ask you briefly about the impeachment of Philadelphia's District Attorney, Larry Krasner. Now for people who don't know the name, he's the model progressive prosecutor. Tiffany Cabán in Queens ran with him as a model though she lost to Melinda Katz. Of course, the impeachment of him in Philadelphia, I don't think they're going to succeed in removing him from office.

Impeachment is a step before that. It's reminiscent of course of how Lee Zeldin just ran for governor of New York, saying that on day one, he would start a process to remove Manhattan DA, Alvin Bragg. Larry Krasner is this towering figure of progressive prosecutor-ness, you're from Philadelphia. Tell us briefly who Larry Krasner is, and what just happened in the Pennsylvania legislature?

Matt Katz: Sure, and it's totally related to what we're talking about with Rikers because criminal justice advocates want to make Rikers safer by keeping people out of jail and that's what Larry Krasner is the model of a progressive prosecutor in the country has tried to do diverting some low level offenders away from jails through alternative programs. He's exonerated several wrongfully convicted people, pulled them out of prison. He has programs for alternatives to cash bail, so he's rolled back the bail system there. He's been popular, he's won two elections in Philadelphia, which is obviously a very, very blue place.

Since the pandemic, as has happened across the country, crime has risen in certain areas, and that has gotten the ire of the Republican controlled legislature in Pennsylvania, and that's why they impeached Krasner. They did vote this week, the Republicans along party lines voted this week, the state house of representatives there, to impeach Krasner. Now it goes to the Senate, it would take two thirds of a vote to remove him from office. It looks like they don't have that, especially because they just lost the seat in the last election. It is an absolute prism in which to look at this divide in the country, which was so starkly clear in the last election, between people who believe that mass incarceration is a stain on this country and we need to do something about it.

Those who think that there's a rising crime and we need to bring back, Bernie Kerik, Rudy Giuliani, tough on crime policies, and it's just a become an a political debate that's playing out from the courtroom in lower Manhattan yesterday to the legislature in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Brian Lehrer: In New York, there's this conversation about how there's no data. That the bail reform that's the center of the debate in Albany has or has not increased crime in New York. Is their data from Philadelphia, that the progressive policies of the DEA, the decarceration in particular, led to increases in crime there or caused other public safety concerns, or that it hasn't?

Matt Katz: There's data on both sides. There's criticism that there's a decline in conviction rate on Krasner's watch, but there's also a declining arrest rate by the police. There is not definitive data on this and it is really hard, I know this as a public safety reporter, it is really hard to try to gauge whether bail reform, whether more progressive policies when it comes to criminal justice, how that makes communities safer or not in the whole. If somebody doesn't end up going to jail for a low level crime, and then they don't commit another crime and then they also are able to stay in their job and take care of their kids and keep their kids off the street in the long run, that is a very complicated thing to quantify.

There isn't a easy statistic to say that one side is right or wrong here, and that's what makes this so ripe for really political manipulation, which is what we saw in the last election.

Brian Lehrer: WNYC public safety correspondent Matt Katz, and I recommend that everybody go to Gothamist and read Matt's article on what has happened to Rikers Island since the federal monitor was appointed a few years ago. Matt, thanks for coming on the show.

Matt Katz: Appreciate that, Brian. Thank you.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.