What Russia and China Are Doing in Africa

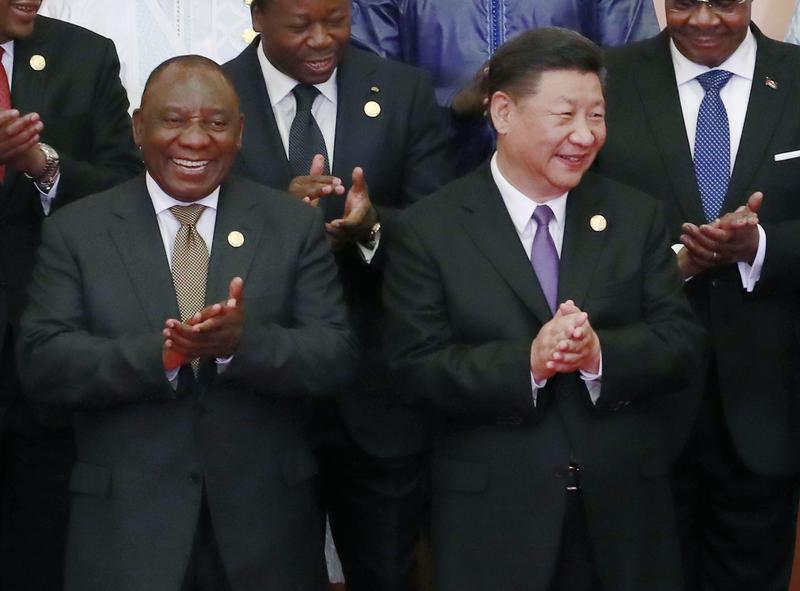

( How Hwee Young, Pool Photo / AP Photo )

[music]

Brigid Bergin: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Welcome back, everybody. I'm Brigid Bergin filling in for Brian today. Today marks the start of the BRICS summit, bringing together heads of state from five non-Western major economic powers. We're talking Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. They'll meet in person over three days in Johannesburg. Notably, President Vladimir Putin of Russia is unable to appear in person due to an arrest warrant issued by the International Criminal Court over war crimes in Ukraine.

He's attending via video call instead. To understand the goals of the individual BRICS member states at this summit, as well as the broader ambitions of the group as a whole, I'm joined by Semafor's Africa editor, Yinka Adegoke. Yinka, welcome back to WNYC.

Yinka Adegoke: Thank you for having me.

Brigid Bergin: Can you start us off with the basics? When was BRICS formed and for what purpose?

Yinka Adegoke: BRICS was formed in 2009. It actually came out of a paper by a Goldman Sachs economist who coined the term BRICS; Brazil, Russia, India, China, initially, and in 2010, South Africa was added to make it the BRICS, the S on the end of that, of BRIC. The idea was basically economic cooperation, multilateral development, the kinds of ambitions you'd expect from these emerging economies, right?

Brigid Bergin: Yes.

Yinka Adegoke: Initially and very early on, as I say, it was very much about economic cooperation, but over time, there's been an emphasis on geopolitical influence. Russia, in particular, has always wanted that, and China more so in recent years under Xi Jinping.

Brigid Bergin: Yinka, can you talk a little bit, and you're starting to get into it, but the power of the member nations in this group and how they compare in population size and maybe GDP, to, say, the G7.

Yinka Adegoke: Right. Here's the thing about BRICS. It's very much about the future of the world, so to speak because here you have already, as they are, 40% of the world's population. You've got China and India in there already. I think they're about 25% of the world's aggregate GDP. These are not insignificant countries as they are, particularly the two really big ones in China and India. The idea is that they are hoping, over time, even though they're informal on, say, the United Nations, or, I don't know, the World Bank, whatever,

they're informal, but there's also a sense that we need to be some counterbalance to the Western hegemony as it is right now, with all the organizations we've mentioned there.

Over time, as China, in particular, although its economy is slowing down right now, but over time, one imagines that this will become a far more influential and important organization economically. As I've said earlier, they would definitely want to flex their muscles in geopolitical terms as well.

Brigid Bergin: Listeners, we can take your questions for our guest, Yinka Adegoke, editor of the Semafor Africa. We're talking about the BRICS summit that is set to begin in Johannesburg today. Are you from one of the nations that is part of the BRICS, that's a BRICS member state? We'd love to hear from you, what are you going to be watching coming out of this summit? Is this something that you're following the news closely? Give us a call or text at 212-433-WNYC. That's 212-433-9692. As I said, you can also text at that number.

I mentioned it when I did the introduction, Yinka, but obviously, a big elephant in the room is the physical absence of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Yinka Adegoke: Yes.

Brigid Bergin: We gave the broad reason for why he's not attending, but how does the war in Ukraine factor into discussions among these world leaders? What does his absence say to all of them? The relationships among these countries, particularly related to the war in Ukraine are not all the same, right?

Yinka Adegoke: Yes, completely. You're spot on. Very different. To be fair, there's nuance. One, it's not very easy to just paint it in a black or white situation, but definitely, you have China there who are somewhat supportive of Russia without actually sticking their necks out all the way. You have India, which is more aligned with the West, but at the same time is obviously importing oil from Russia on the side as well. Then you have South Africa, which has been in this very awkward and interesting situation with President Ramaphosa where they are constantly trying to show that, well, we're not aligned with anybody, and we're neutral.

At the same time, so much of their economy in South Africa is linked to the West, so they have to also toe the line very carefully. It was interesting, we at Semafor with our newsletter, a few times a week, almost every story for about two months was about, will he or won't he, and what does this mean if he does? It was that. It just went on and on because there's so much tension. Listen, President Ramaphosa has enough problems and enough challenges in South Africa as it is. It's not in the strongest of positions, and this was a huge issue.

At one point, he described it as it would be a declaration of war if they arrested Putin on South African soil. They obviously didn't want that, and that went on for a bit. It's different for all the different countries. They have different things they're more concerned about, but it's also, to also take us back a few weeks, Ramaphosa led a group of African leaders to both Russia and Ukraine to broker peace between both countries and to see if there's a way to end this. Obviously, as you know, Ukraine is a particularly important country in terms of its production of wheat, of grain.

Brigid Bergin: Sure.

Yinka Adegoke: It's a big, big, big food supplier to the world, including many African countries. The fact that so much of its supply has been stifled by Russia and by everything going on is a big issue for many countries. That's also on the minds of all the leaders, and that will come up as well.

Brigid Bergin: I want to bring in one of our callers. Aaron in Manhattan asks, I think, a pretty good global question. Aaron, welcome to WNYC.

Aaron: Thank you very much. I appreciate it. The question is, I figure that if these large powers get together and they actually want to create a better world, that the goal wouldn't be some kind of hegemony or political, or economic power over one another. My question is, is the goal to come together to solve any problems in a different way, to actually have a conversation, or is it to assert military might and the grab for other property?

Brigid Bergin: Yinka, what are your thoughts on that?

Yinka Adegoke: That's a great question. It's a great question. Listen, let's say what they say. What they say is, "We want to have economic cooperation, we're emerging economies, and we want to find ways to work together," particularly in what we broadly call these days the Global South. "To work together and to trade with each other more efficiently." One of the big issues actually, which we haven't brought up yet, is this de-dollarization of the global economy. That if, say, Nigeria wants to buy something from China, they have to first change their currency into US dollars to buy something from China, or if Kenya wanted to import something from Paraguay, it would have to, first of all, transact in US dollars.

There's this idea and discussion about how do we get ourselves to depend less on this dominant US dollar? Now, to be clear, this is not the United States' direct fault in each individual case. This is simply about the economic might of the United States at this time in history. That's, as countries like China and India rise, they want to see ways in which they can reduce that reliance on the US dollar. Obviously, if you're President Putin or President Xi, you also have geopolitical reasons why you want to rely less on the United States. In just everyday practicalities, it's very tough for particularly the smaller economies.

They will be looking for ways to figure this out. This is one of the key topic areas. As for military might, to be fair, this is not really an area of discussion much in this particular context. The way it happens or the closest it comes to that is this kind of geopolitical cooperation between countries, right?

Brigid Bergin: Sure.

Yinka Adegoke: If you're Russia, you find yourself isolated because of the Ukraine conflict, and you want to have another forum in which other countries can work with you or partner with you.

Brigid Bergin: I want to pick up on a thread that you were talking about there, Yinka, related to some of the economics discussions that are happening. You said that one of the objectives of this group is to challenge the US supremacy over the world economy, and the rule of the US dollar. My understanding is there's been some discussion of a BRICS currency, but that it is not, again, like many of these issues, something that all of the member states necessarily agree on. Can you bring us up to speed on where those conversations stand and what are some of the other paths they might be looking at to achieving this goal of competing with the economic dominance of the West?

Yinka Adegoke: Yes, the idea of a BRICS currency is one of those things that, particularly for those of us in the media who are writing stories or have stories on the radio or TV, or whatever, it sounds like a really interesting idea, but it's nothing more than that. It's an interesting idea. The economic reality is, who would fund the BRICS currency? You would need countries, at least two or three of those members, to be really very liquid, and that's not China right now, which is dealing with its own economic challenges. Its economy is slowing down.

India is doing okay but has enough domestic issues for it to be concerned about. Brazil is not in the position. South Africa is tiny relative to those countries, so that, it's not realistic that it will happen. You're right, they will have to think about other ways, and they're certainly thinking of this in terms of how they trade together. I think India has been pushing this to try and get countries nearby to trade with the Rupee rather than having to go use a dollar. The same thing with China as well, also using its currency in trading with other countries.

More of those discussions are happening. Are they dominant? Are they huge yet? No, but maybe over the next couple of days, they'll figure out ways to make this more of reality or to make it more common. These are the kind of things that take a long while to sort out.

Brigid Bergin: Absolutely.

Yinka Adegoke: One of the challenges that they have with BRICS is it's this consensus-led organization. Everybody has to agree to everything. You've got these huge countries, it takes a long while for them to figure these things out and agree on them. We'll see how that plays out.

Brigid Bergin: If you're just joining us now, I'm speaking with Yinka Adegoke, editor of Semafor Africa on the topic of the BRICS summit that began in Johannesburg today. We'd love to hear from listeners, particularly our international listeners or listeners who are from one of the countries that is a member state of BRICS or just listeners who are from countries that may be thinking about the US Western influence versus the influence of Russia or China in your home country. We'd love to hear from you. Yinka, I want to read you one text that follows up on a theme we were just talking about related to the BRICS currency.

That listener texted, "BRICS isn't talked about enough on US news. It will destroy the dollar, which means the end of the US dominance and the world's reserve currency." That came from Corina in Queens. If you agree with Corina, give us a call. Tell us what you think, or you can text and share a different perspective. The number is 212-433-WNYC. That's 212-433-9692. Again, we would love to reserve some lines for some of our international listeners who may be thinking differently about this issue about Western and US influence versus the influence of some of these bigger players in the BRICS Coalition, Russia and China in particular, or maybe you're from Brazil or from South Africa, and you have a different perspective about being in this particular group with some of these other nations.

We would like to hear your perspective on that. Yinka, one of the things that I thought was interesting is the creation of the New Development Bank, the BRICS counter to the IMF and World Bank. It's seen as a major achievement of this group. Can you talk a little bit about what it is and what its economic capacity is?

Yinka Adegoke: [chuckles] It's interesting that you say it's seen as a major achievement of the group. It's often seen as the only achievement of the group.

Brigid Bergin: Making it very major.

[laughter]

Yinka Adegoke: [unintelligible 00:16:37], exactly. I know that sounded like a bit of a putdown, it wasn't necessarily so. It was just to point out that because of that kind of consensus-led thing that I mentioned earlier, they haven't done very many formal things, but they did do this one thing. One of the big issues we've seen over the last decade, and the voices have picked up a lot on this within BRICS, outside of BRICS, it's a big issue as to the reliance, the continued dominance of the development finance by the World Bank and IMF.

What we in the business called the Bretton Woods organizations. A few countries have, and a few- what should we call them?- continental groups have created development banks, but this one clearly with three of the largest emerging markets in the world, four of them actually, it could be particularly influential. It's based in Shanghai. It has lots of numerous projects developing, building roads, maintaining roads, bridges. All the stuff you expect development banks to do in developing and emerging markets. The hope though is that it becomes increasingly influential because it's not just about the projects.

It's also about the kind of influence. If you think about the kind of influence that the World Bank has on the entire development space, you start to understand that what they really want some other organizations to be able to, as we say, to use their word, counterbalance this, it's not just about building more roads and building more [unintelligible 00:18:41]. It's about building them on terms that we can have some influence over. China, in particular, really cares about this. You can see that in their influence in the whole discussions around debts.

They've lent money for infrastructure projects around the world, particularly in Africa, but not just Africa, Southeast Asia as well, and Latin America. It's something of, it's not just about development, it's also about a battle of ideas. Like, "Yes, you've done it this way and you've had control over the way it works. We want to have some say over how it works because these are our countries."

Brigid Bergin: Sure.

Yinka Adegoke: China wants to be seen as a leader in the Global South, and all these people are our friends. Eventually, if you think about it, they're playing for the long term. They're not playing for today. In only about 20 or 30 years time-- What year are we? 2023. By 2050, one in four workers in the world will be African. If you have an organization which includes Africans as well as Chinese and Indians, you have organizations which have the vast majority of the world's population.

Brigid Bergin: Right.

Yinka Adegoke: It's a long-term game for them. It's not just about the bank for today.

Brigid Bergin: Then on top of that, a huge issue at the summit is expansion of BRICS, right?

Yinka Adegoke: Yes.

Brigid Bergin: With China and Russia seemingly pushing for more rapid inclusion of some of the applicants. I understand at this moment more than 40 countries have expressed interest-

Yinka Adegoke: Correct.

Brigid Bergin: -in joining, and 22 nations formally submitted applications. Can you talk about what are the implications of expanding this alliance of nations if some of these applications are accepted? We had a caller who wanted to actually correct me that Saudi Arabia was already a member of the BRICS, but my understanding is--

Yinka Adegoke: No, that's not correct.

Brigid Bergin: Okay. Talk about some of the folks who are applying to become members of this and what the implications are of that.

Yinka Adegoke: Yes, in fact, this will be the number one topic this week. You're correct. More than 40 countries have applied, or at least expressed interest will be the more correct description of what has happened so far. It includes Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Venezuela, Congo, Ethiopia, Kazakhstan. Really far wide range of countries, and all with various degrees of development, all with various degrees of ambition, all with various degrees of funding because none of this stuff is for nothing. Saudi Arabia, in particular, could have a really big influence because they are clearly more liquid than most countries in terms of raw cash.

Some countries will be extremely controversial and will be problematic, particularly for the West. If, say, Iran is near the front of the line for countries that have expressed interest, Venezuela I mentioned, that will be a bit of an issue for the West. Frankly, BRICS hasn't so far, and I could be wrong on this in the future, but so far hasn't been positioned as a confrontational type of alignment, right?

Brigid Bergin: Sure.

Yinka Adegoke: The idea that countries like Iran or Venezuela would be the first to expand with seems unlikely, but I could be wrong on that. It depends on so many different things.

Brigid Bergin: Yinka, I want to bring some of our listeners into this conversation. Let's go to Logan in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Logan, thanks for calling WNYC.

Logan: Good morning. Thank you for accepting my call. I'm listening to your guest. At least he's not the usual pro-American propagandist that NPR has been bringing on lately. I've been listening to this program for years. Anyways. He's saying that he doesn't think military strength is behind this whole issue. Why then would America spend so much money on the military instead of domestic programs that would really help people?

Brigid Bergin: Logan, thanks for that call and that issue. We're so glad to have all variety of listeners to The Brian Lehrer Show and to WNYC. Yinka, I think what I heard in that call was some skepticism that this type of alliance isn't one that is being fortified for military purposes, that it is a pure economic alliance, but I think probably part of that conversation would also get to the fact that an economic alliance could then turn into a military alliance because you would have a lot to protect if you have come up with-- if you want to respond to that at all.

Yinka Adegoke: Yes. I still stick to the point that that's not their primary purpose. I don't say that because I feel like it's all flowers and gardens, and that kind of thing, and no one ever thinks about military might, but more because, look at the countries who are in here, look at the leading countries. China and India, they can barely be in the same room. Prime Minister Modi and President Xi barely see eye to eye. They already have their border problems as it is, which is, there's a lot of tension there. If their primary purpose was military cooperation, this is perhaps not the way they will go about it or these will not be the countries that will be members.

Now, your listener is correct in one sense. Over time, who knows where this can go, right?

Brigid Bergin: Sure.

Yinka Adegoke: This will be the concern of the White House or anybody else in Washington DC. watching this stuff. Even when I say, and this is a personal opinion, of course, that this has not been a very effective organization, that doesn't matter to the White House or to those who care about US foreign engagement. They will understand that just seeing all these countries together feels like you're just watching all the countries that have complained about the United States' dominance for years in one room together. Just in a kind of optic sense, it's a challenge.

People don't have to pull out nuclear weapons and threats, and military might. Just the very fact that these countries are all talking to each other, the US is not part of it, will be of some concern and of interest. You can be sure that they're watching closely this week.

Brigid Bergin: Yinka, China is currently engaged in development projects across Africa where this summit is taking place, as well as Latin America. What's the significance of Chinese development projects in the Global South with regards to the summit?

Yinka Adegoke: I'm not sure whether that will come up directly. It comes up indirectly for two reasons. You're right, China is involved in a lot of these projects. I'm sure you're familiar with the Belt and Road Initiative, which they put in place about, I think, it's nearly 20 years ago now. Yes, 2013 was when it really kicked off. Yes, they will continue to push their position as your go-to infrastructure partner to build bridges and roads, and all the rest of it, but there's also the discussion, which will be happening on the side with some of the other countries, about the level of debt that has been racked up over time with countries who have built things but can't quite pay back.

It's caused a lot of consternation. The United States has been very vocal about this, about the fact that so many countries have found themselves in precarious situations in terms of the level of debt that they've racked up building all these projects. Some that aren't great, and some that frankly end up being white elephant projects or whatever. That will come up. It won't be the primary topic of discussion, but it will come up this week.

Brigid Bergin: On the flip side of that, despite it being such an economic powerhouse, China is also experiencing this substantial economic slowdown.

Yinka Adegoke: Yes.

Brigid Bergin: Again, how does this affect China's goals for the summit, and its standing among other members, whether it's an explicit conversation or just something that is the backdrop of some of those conversations?

Yinka Adegoke: Yes, I think it will be the backdrop of the conversations. Just to even put it in context of how important this conference is, this is only the second time President Xi has left China this year, it's my understanding. I think the only other time was to Russia for a short visit. This is as important as it's going to be for him as the president and to make sure that China is still seen as influential with these countries. This is where they see the future of the world. They want to continue to encourage development and for China to be seen as the leading partner in the Global South. This is something that, I think, in particular, his presidency has really pushed. We will see a lot more of that over the week.

Brigid Bergin: I want to go to another caller. Let's try Jeffrey in Jamaica, Queens. Jeffrey, thanks for calling WNYC.

Jeffrey: Thank you for being there. I do not hear much talk about democracy, and that Russia and China are not democratic. With all of America's faults, I would like to see someone struggle to keep us where we are. Even if it's because of nuclear missiles, I really don't want North Korea, and Iran, and Afghanistan to be the-- [sound cut]

Brigid Bergin: Jeffrey, I'm sorry. We're having a hard time hearing your line. It's a little bit low. Yinka, I think what we were able to hear was some reaction to this idea that these are nations that don't universally have democratic systems. Obviously, India is in this group, which is a democracy, but there are a lot of people who challenge some of the strength of its democratic operations at this point. To what extent is democracy and democracy-building at all in any way part of these conversations given the members of the BRICS nation states?

Yinka Adegoke: It's a bit like our earlier points or the earlier question about military cooperation, what have you, yes, that's not going to be on the agenda at all. [laughter] It's just not.

Brigid Bergin: Of course.

Yinka Adegoke: How could it? You have China, you have Russia, and most of the other countries they're trying to get in there, like Saudi Arabia. It's not a primary conversation, which is why we talk a lot about it being about the economic cooperation and trade. Now, where that leads to is what we don't know, but it's almost like the reason it exists is so that we don't have to have these conversations about you asking me about democracy just because we're trying to develop our country.

Brigid Bergin: Sure.

Yinka Adegoke: You have to think about it from their perspective sometimes. It's like, "Sure, yes, we'd like to have this discussion about trade or what have you, but why do you have to bring up all this other stuff that has nothing to do with trade?" That is the way they see the world. I'm not saying I-

Brigid Bergin: Right.

Yinka Adegoke: -necessarily agree with that, but I'm just saying that's the way they see the world.

Brigid Bergin: Absolutely.

Yinka Adegoke: "Let's have these discussions separate to each other." They're not going to go there. By the way, particularly, this is led by China because it's the largest economy of all of those countries. China's position is often, "We do not interfere in the affairs of other countries." They can sit there with a democratic country regardless of the quality of the democracy like India, and it's not in conflict with the way they operate, right?

Brigid Bergin: Right.

Yinka Adegoke: They will go to any country, and they don't care if it's a military leader, as we've just seen in Niger or whoever, they will work with whoever they need to work with. This is just not a topic of conversation, which does not mean you couldn't say they were anti-democratic in the sense of actually doing something to stop democracy, but they're not trying to--

Brigid Bergin: It's not a topic. It's not on the agenda.

Yinka Adegoke: It's not a topic of discussion. Right, exactly.

Brigid Bergin: Yinka, I am assuming that we will be able to get updates on what happens at the summit from Semafor's upcoming newsletters. Is that right?

Yinka Adegoke: Yes, correct. We're all over this. You can sign up for it at semafor.com. Yes, this is a big one. It's probably the biggest diplomatic event on the continent in quite some time.

Brigid Bergin: We will leave it there for now, but much more to come on that. My guest has been Yinka Adegoke, editor of Semafor Africa. Thank you so much for joining me.

Yinka Adegoke: Thank you for having me. It's a great discussion.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.