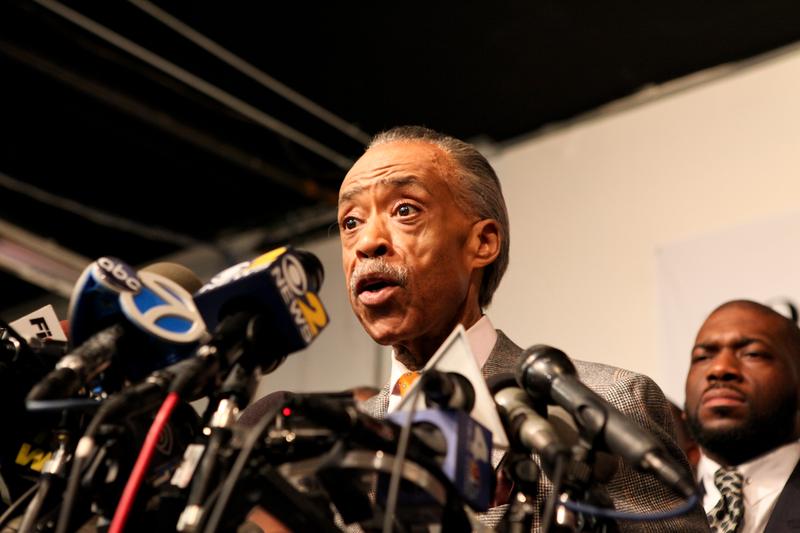

Rev. Al Sharpton's Call To Action

( Stephen Nessen / WNYC )

[music]

Announcer: Listener-supported WNYC Studios.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. We'll get more debate reaction now and also talk about the extraordinary era of the crossroads for racial justice that we are in, no matter who wins the election with the Rev. Al Sharpton, who has a new book called Rise Up: Confronting a Country at the Crossroads. Rev. Sharpton is also the host of PoliticsNation on MSNBC weekends at 5:00 PM Eastern Time, host of the daily syndicated radio show Keepin' It Real, and of course, founder and President of the influential civil rights organization, the National Action Network. Reverend, thanks for making this one of your stops as your book comes out. Welcome back to WNYC.

Rev. Al Sharpton: Thank you. Glad to be with you.

Brian: I want to start with last night's debate. I'm going to replay the clip we started the show with last hour because it might be the only news that matters from last night's debate. Trump's reply to this question from moderator Chris Wallace of Fox News, when he asked, "Are you willing tonight to condemn white supremacists and militia groups and to say that they need to stand down and not add to the violence in a number of these cities as we saw in Kenosha and as we've seen in Portland?" That was Chris Wallace's question verbatim, and the president replied like this.

President Trump: I would say almost everything I see is from the left-wing, not from the right-wing-

Chris Wallace: What are you saying?

President Trump: I'm willing to do anything. I want to see peace.

Chris: Then do it, sir.

President Trump: Say it. Do it. Say it.Do you want to call them-- What do you want to call them? Give me a name. Give me a name.

Chris: White supremacists. [crosstalk]

President Trump: Stand back and stand by, but I'll tell you what. I'll tell you what. Somebody's got to do something about Antifa and the left because this is not a right-wing problem--

Brian: They went on and on. The leader of the Proud Boys later tweeted, "Standing by Mr. President." Mr. Sharpton, Rev. Sharpton, apologize. Your reaction.

Rev. Sharpton: I think that it is extremely disturbing and downright offensive to most people, that you have the President of the United States that cannot unequivocally denounce a group whose pronounced agenda is white supremacy and violence. I've been involved in civil rights all of my life. I cannot think of any president, and I've disagreed with many, that would not outright denounce a group like the Proud Boys.

This president had the opportunity in the first debate of his re-election campaign to unequivocally say, "I do not side with white supremacy. I do not side with militia groups, and I denounce them," as many of us have denounced people, or that he claims are on the left that have common cause violence in the name of fighting for causes we believe in. He did not do that. I think it shows us who he is and what he stands for. It compels us as he tells them to stand by for us to rise up, which is the title of my book.

Brian: On the flip side of that, after the debate, Trump challenged Biden to name one law enforcement group who endorsed him as opposed to Trump, and Biden couldn't. Here's a little bit of that.

President Trump: He doesn't have any law-- He has no law enforcement, almost nothing.

Joe Biden: That's not true.

President Trump: All right, who do you have? Name one group that supports you. Name one group that came out and supported you. Go ahead. I think we have time.

Joe Biden: We don't have time to do anything.

Brian: He didn't seem to be able to name one law enforcement group that supports him. What do you think that says about the politics of the police today?

Rev. Sharpton: I think it says a lot. I think when you look at the fact that we are in the middle of a real reckoning of how we deal with the police, particularly in the Black community, and the issue of how we reimagine policing, how we deal with police killings and harassment, to act as though now it's us against them is a climate that I think is not good for the police or the community.

I'll give you an example. Right in New York, a policeman was killed about two years ago, and I went at the request of the family of the deceased police officer, met with the family, they invited me with no suggestion of mine to come and speak at the funeral. I agreed. When it was announced publicly, the police union absolutely rejected it, said he shouldn't speak, caused an uproar. I call the family and said, "Look, I don't need to be a distraction, you're grieving. I'm not coming. Remove me from the program." National Action Network and I still sent our $5,000 to the policeman's family's fund they set up for that young man.

This whole thing of that you, if you question policing that you're anti-police, or that you and the police unions are diametrically opposed, is something that I think they cause. We are willing to deal with police. I've dealt with the last several police commissioners, but I've challenged police policy. I think that for Donald Trump to act like having the endorsement of law enforcement, which in many ways are fighting on the other sides of issues is some litmus test, is ridiculous.

Brian: I happen to see a Fox News notification go by a few minutes ago. I haven't had a chance to look deeply into it, but it was from Fox News. It said, "The sheriff of Portland refuted Trump's claim in the debate last night that he had endorsed Trump." Just throwing out that as a little fact check that interestingly-

Rev. Sharpton: Interesting. Interesting.

Brian: -came from Fox News this morning across my device. In the book, you tell the story of the day after the 2016 election when Donald Trump called you on the phone and said of all people who would-- I'm sorry, said that of all people, you would understand his win. It would be you. Why do you think he thought that and how right or wrong was he?

Rev. Sharpton: What happened was it wasn't the exact day after. It was a couple of weeks after.

Brian: Sorry.

Rev. Sharpton: I had that morning appeared on Morning Joe and MSNBC. Joe Scarborough asked me about Donald Trump, and how did he get these voters in the Pennsylvania and Appalachia, Kentucky. I said, "You got to understand. Donald Trump comes from Queens, New York. Even though his family, his father, specifically had money, they were not part of the inside crowd of the real estate establishment with the Park Avenue kind of business tycoons. They were the outer-borough, felt like they were rejected, felt that they were looked down upon, and he always had a chip on his shoulder that he had money, but they did not respect him. He was able to translate that," I'm talking now to Joe Scarborough.

"He was able to translate that chip on his shoulder, that sense of rejection to others, notwithstanding that he had a lot more money than they did. You've got to understand New York and the difference between what is perceived as a Manhattan elite and the outer-borough guys that never felt embrace. He was not seen at the power places having breakfast or lunch. That was not a crowd that embraced him and did not see him in many ways as legitimate."

When I had got off the show, I remember we were in a board meeting at National Action Network, and my cell phone rang. It was on silence. I looked down. I didn't recognize the number. I didn't answer. He call right back. I stepped out of the room, and I answered and said, "I'm in a board meeting, I can't talk." The voice said, "Will you hold on for the President-elect?" I was a little stun, and Trump comes on, "Al, I saw you this morning on Morning Joe. You get me. You understand me. You an outer-borough guy from Brooklyn. You know how to elite looked at both of us. We were outside as we were the ones that didn't understand the elite, and can you believe it now I'm the President-elect of the United States?"

I said, "Frankly, I do have a hard time believing." I said, "but we were two different kind of outsiders." I think what he was trying to do, was tried to compare me being an outsider for many reasons and him being an outsider for many different reasons. He invited me to come meet with him in Mar-a-Lago and I said, "No, I'm not going to do that. If you want a meeting, you should meet with all of the leaders of National Civil Rights Organizations. I'm not doing the photo-op." I think he always tries to say to people something that makes them feel like he is similarly situated with them though he definitely is not, and his policies are antithetical to that kind of commonality.

Brian: Can you talk about your side of that experience in the early days? Because you read about the structural changes that were taking place in the city at the time, including the departure of manufacturing jobs, the rise of the finance and real estate sectors, the red-lining that was still taking place, and more. For people who might be younger or newer to the city, can you describe more about what was happening economically to the Black community in New York at the time that you were coming up?

Rev. Sharpton: Yes. When you had the migration from the South of many Blacks that came to New York, the North in general, but specifically New York like my parents. My mother was from Alabama, my father from Florida. They came to get work, and they worked in manufacturing jobs. They could get work in various places that were available. As the economy in New York shifted from manufacturing to finance, it became a more closed economy, opportunities dried up and they could not get that kind of employment easily. Those that did survive and expand their families, they could not get the bank loans and the home loans. It was a very isolated kind of existence that they had to try and struggle through.

I was born and my parents having to deal with that. I was born in Brooklyn at a time that my father owned the house we lived in, but couldn't get remortgaged. He could not have various opportunities. He ended up owning the store on the corner and he had some houses, but a lot of it was in a financial climate that you could not thrive. We grew up into that as we saw the transition of New York go more from where you could be a laborer to where if you didn't have financial skills and certain educational backgrounds, opportunities began to dwindle.

Brian: Let's notice our guest is Rev. Al Sharpton who's got a new book called Rise Up: Confronting a Country at the Crossroads. We can take some phone calls for him on things from the book like we've been talking about or things from the debate last night, which we're going to play another clip of or things related to the crossroads that the country is at right now on racial justice and other things. 646-435-7280. 646-435-7280 or tweet @BrianLehrer.

Another moment in the end debate, Reverend, where Trump engaged in-- I don't even know what to call it. Maybe barely concealed racial coding was this. Interestingly, it ends with Biden flipping it to the issue of COVID-19, but also maybe painting life in the suburbs from his end as more integrated than it really is. Listen.

PresidentTrump: If he ever got to run this country and they ran it the way he would want to run it, our suburbs-

Joe Biden: We would run it the way suburbs-- [crosstalk]

President Trump: -would be gone. By the way, our suburbs would be gone and you would see problems like you've never seen before.

Joe Biden: He wouldn't know what's suburb unless he took a wrong turn.

President Trump: I know suburbs so much [crosstalk]

Joe Biden: I was raised in the suburbs. This is not 1950. All these dog whistles and racism don't work anymore. Suburbs are, by and large, integrated. There's many people today driving their kids to soccer practice [unintelligible 00:13:45] Black and white and Hispanic in the same car as there have been any time in the past. What really is a threat to the suburbs and their safety is his failure to deal with COVID. They're dying in the suburb.

Brian: Rev. Sharpton, your thoughts about that exchange?

Rev. Sharpton: I think that there are pockets in the suburbs that have a lot of Blacks and Latinos. Though I do not agree that they're totally integrated. You can go in suburban communities and you still have the Black side of town and the white side of town, whereas in the past you didn't have Blacks or Latinos out there at all. The other thing that I think has to be factored in is gentrification. That is, there are many whites that move back to the inner city and a lot of Blacks are moving to the suburbs because that is where they're being forced to go.

I think Donald Trump is talking about back in the day-- He's 19 years older than me. Back in the day when he was coming up and he and his father was shooting for racial discrimination and housing, where it was defined the suburbs was white and the inner-city was Black. With gentrification, we're seeing many inner-city Black communities having a lot of whites that have moved in and Black forced out. I think that Biden is generally right. It's a different landscape, though I would say that there is not full integration in the suburbs or even in the inner-city. We're in transition and a lot of that largely because of gentrification.

Brian: Let's take a phone call. Glenn in Brooklyn. You're on WNYC with Rev. Al Sharpton. Hi, Glenn.

Glenn: Good morning. Good morning to both of you gentlemen. There was a comment made about the police unions and their [unintelligible 00:15:34] the mentality and posture. I'm a retired officer. I spent 20 years with New York City Police Department. I can tell you there's a certain amount of animus that exists even within the organization with its own members.

Given all the things that are taking place right now, I sincerely doubt that there has been any union official from any of the unions that have vowed to reach out to any of the Black officers that happened to be members of those [unintelligible 00:16:00] unions, to find out from them whether or not any of these things have affected them personally, whether they feel it's true, and how they think these things can be resolved or dealt with.

Brian: As a retired police officer, do you have an impression of whether the language, the tone as well as language that we hear from people like the head of the Police Benevolent Association in New York really represent the rank and file?

Glenn: It represents a segment of the rank and file. That segment is not these segments of those officers that are of color, that are Black and brown. That's been an unfortunate reality within that organization for a long time. I think it's extremely difficult that the leader of the PBA has not seen fit to remain neutral and not posture himself to where he now presents to the public that this is perhaps a perception that all police officers have by him going in and speaking at the RNC convention. That's something that I think he should have had the foresight not to do.

Just the idea that he didn't have the wherewithal to understand why he should not do that. It's also indicative of how he conducts himself, assess himself as a leader of an organization and what does rank and file tend to follow.

Brian: Glenn, thank you very much. Rev. Sharpton, despite the way we in New York may hear Pat Lynch, head of the PBA, on a year and year out basis. This was the first time as I understand it that the group ever actually endorsed a presidential candidate. I guess from their point of view, the police feel under siege too right now. How would you address that and what Glenn said?

Rev. Sharpton: I think Glenn raises an interesting point. Many unions in the city of New York and nationally, make endorsements but they usually will find a way to get the members to weigh in to where they want the support to go, and really vet out with their membership before they do an endorsement. I would be very curious to find out if the rank and file was involved or even questioned or given an opportunity to weigh in before the speech was made, supporting President Trump's re-election.

Don't forget that Mr. Lynch spoke on the night that Donald Trump took or spoke to his acceptance of the nomination of the Republican party at the White House. This was a major event and a major feature. If Mr. Lynch had not in many ways found out the political thinkings of the membership, then there was a false image given though he was speaking for all police. I also think Glenn, the caller, is right that I've had many officers, Black and white, tell me at various cases that National Action Network and I were involved in that they disagreed with the position of the union.

For example, years ago, when we did the Amadou Diallo movement or the Sean Bell movement, where they would pack the court, supporting the police and there was some police that's saying, "I think the police were wrong. I think they did overreact. I think that they did break laws." The Eric Garner case just six years ago, the same thing. I think that it is absolutely right that there are different feelings among some officers which is why years ago you saw the forming of 100 Blacks in law enforcement who were Blacks in law enforcement, in the police department that took positions against the union heads.

Brian: Related to this, you write in the book against what you call purity politics. It sounds in that section of the book, at least as it struck my eye like you're writing about the religious right almost. "If you take such a hard line for your morality, how is there ever going to be political negotiation that has to appeal to a wide range of people?"

You related this to the defund the police movement. I read that you said on Morning Joe and I read it in the New York Post, but I'll assume the quote of you is accurate that to take all policing off the table is something that I think a latte liberal may go for as they sit around the Hamptons discussing this as some academic problem, but people on the ground need proper policing. Can you talk about the defund the police movement in the context of purity politics as you write about it in the book?

Rev. Sharpton: When I write about the purity politics as those that are on the right that feel that you've got to check off every one of the boxes of what they claim to represent a religious belief and that there's no room for discussion or debate. There's not even room for how one may interpret the same scriptures differently than others. The same must be said on those on the far left. When the question was raised about defunding the police, my response and the position that we've taken a National Action Network is, "Yes, we need to distribute resources differently to keep putting money in the same areas of policing that is not working is foolish."

At the same time, we need to have a re-imagined police department that can take care of crime in the streets, stopping gun trafficking, dealing with those that inundate our communities with guns that have now-- Again, we've seen the rise of gun violence in the city, but at the same time deal with community policing and mental health needs and dealing with how they operate in the schools and places of education and having people call to the scene of a crime or an alleged crime that could give some kind of counseling and talking and looking into the situation, showed the policemen using lethal force.

That is how I think we ought to deal with it. There are those that say, "No, we don't need any policing at all." We've talked about the latte liberals. That may be good for those that live in communities that are not inundated with crime and that are not facing communities where there're guns easily available, even though there's no gun manufacturing plants or bullet manufacturing plants there. You can sit back in safe environments, sipping a latte talking theory. Those on the ground that have to deal with the reality can't afford to embrace those theories.

It is the height of being stressed out when you are living in communities where you are afraid of the cops and robbers. If you're being robbed, you're afraid to call the cops because you don't know if you're going to be victimized. We need to be able to reimagine policing where that's not the case. What a lot of people, Brian, do not deal with though it was covered, but very few times is it mentioned after the initial coverage is a month after I did the eulogy at George Floyd's funeral in Minneapolis. I did a eulogy at the funeral of a young 17-year-old young man here in the Bronx, New York, that had been killed by a stray bullet with gun violence.

Two weeks later, I did the eulogy at a funeral of a one-year-old child in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn killed the same way with a stray bullet. I'm just as adamant about gun violence and about those that have inundated our community with guns and those that would participate in gun violence as I am against policing that also act in a reckless way using firearms.

Brian: Pat in Peekskill. You're on WNYC with Rev. Al Sharpton. Hello, Pat.

Pat: Hi, Brian. Thanks a lot. First-time caller. Rev. Sharpton, thank you for all you do. Rev. Sharpton, I wanted to get your comment, Mr. Sharpton. I don't know if you heard Jonathan Alter on Brian's show earlier. He was [unintelligible 00:24:31] about almost his fear of putting a protest in the wrong direction, meaning away from the impulse, the importance of maybe redirecting that energy from the protest right now to the importance of voting and coming together as one people to oust the president.

Brian: Pat, thank you. Reverend, I don't know if you've heard them. I know you must know Jonathan Alter from MSNBC, but he was on the show last hour, commenting on the debate and he says, "Our democracy is at stake unless Biden wins this election and can take office." He wants to see the protests of all kinds for justice stand down for the moment and just focus everybody's energy on doing phone banking and swing states and other things and also not give Trump any more excuses to point to anything going on in the streets just for a few weeks. What do you think?

Rev. Sharpton: I did not hear Jonathan, but I would not say that the protests need to stand down, but I do think that we ought to be engaged in voter mobilization and that we need to use the energy to get people out to vote. I think you can do both at the same time. I think we need to focus on why we're telling people to vote. That is so that we can bring about laws that would give prominence to the change we seek.

When we had the march on Washington just last month, tens of thousands came to Washington. The theme of the march was we wanted to see the George Floyd policing and justice Act passed in the Senate. It has already passed the House. It would be making it a felony for police to use suppression, whether it is a choke-hold as in Eric Garner, whether it is a knee on the neck as in the case of George Floyd, that would be illegal. Where police records would be made public. If there's a record of several complaints of harassment or of doing things wrong, where the police would lose immunity from being liable.

A policeman, I think, would operate different if they knew that they could be sued. They could lose their house or car. They would think differently before they just operate in a certain way. It is past the House. We need to deal with demonstration and legislation and you can't get legislation without lawmakers making laws. I think the spirit what Jonathan says is right. We need to put energy into voting. I don't think we have to stop demonstrating at all to do that. I think we can walk and chew gum at the same time, which they did in the '60s. The civil rights movement dramatically affected the '64 presidential election of Lyndon Johnson, but Dr. King never stopped marching to do it.

Brian: As we begin to run out of time, I want to ask you to take us back into one more piece of New York City history because you end the book vowing that even after you are laid to rest one day, your spirit will still be chanting, "No justice, no peace." Would you talk about the origin of that phrase that you popularized starting in the 1980s? "No justice, no peace." Did it originate with the white mob killing of Michael Griffith in Howard Beach, Queens back then? To relate it to today, there are many people, as you are very consistently over the years call for nonviolent protest, who hear the "No peace" part of that phrase as threatening violence.

Rev. Sharpton: No. In 1986, young man, Michael Griffith, was killed in Howard Beach for being in the neighborhood. He was there. The car broke down, him and two others, and he was chased in the Belt Parkway and killed. The movement that started out of that, that I was a part of, started that chant, "No justice, no peace." I don't know exactly who started it. You're right. I helped to popularize it.

The idea was not violence. The idea was there is a difference between quiet and peace. People would say, "No, let's just shut up. Don't march. Don't protest. Don't raise the issue. Just let's have peace." No, what they really meant was let's have quiet. Peace is the presence of justice and fairness for everyone and in order to have peace, you must have justice. We're not saying be violent. We're saying that don't be quiet. Let's stand together and demand what is right. When I say, "No justice, no peace," I'm saying that until we have justice, there cannot be peace. It can only be quiet in justice and everything remain the same. We cannot have everything remain the same. We must continue to do what is necessary to bring about justice therefore peace will accompany that.

Brian: Rev. Al Sharpton is host of PoliticsNation on MSNBC weekends at 5:00 PM Eastern time. Host of the daily syndicated radio show, Keeping It Real, founder and president of the National Action Network, and the author now of a brand new book called Rise Up: Confronting a Country at the Crossroads. We are at a crossroads, Rev. Sharpton.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.