[music]

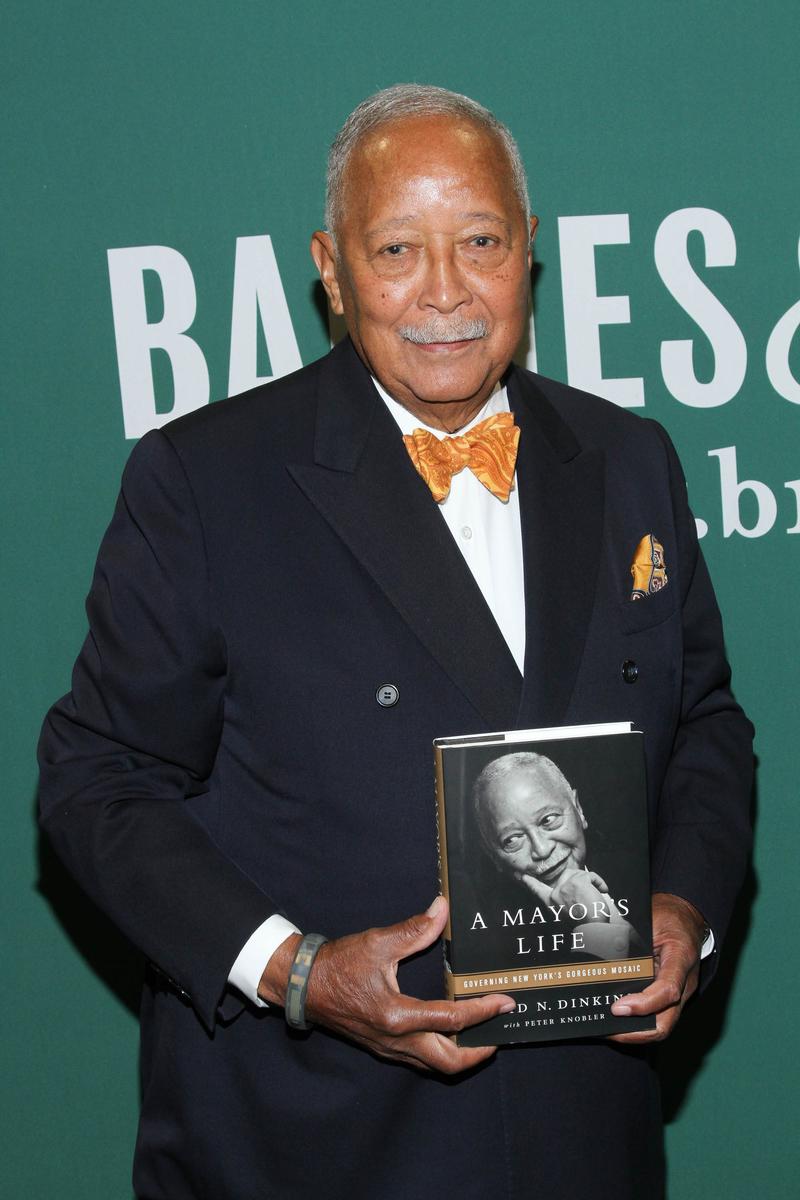

Brian Lehrer: It's the Brian Lehrer show on WNYC. Good morning again everyone. I want to play a few clips of Mayor David Dinkins on this show. Mayor Dinkins who has now died at age 93. Who was elected in 1989, and for the 20th anniversary of that in 2009, Mayor Dinkins was a guest on this show and I asked him this question. Looking back, why was 1989 the right time for you to run for mayor, and for the city to elect an African-American for the first time?

David Dinkins: First, I have to quickly point out that I never felt that, "Gee, I can't wait to become mayor." I ran three times for Manhattan Borough President before I succeeded. Indeed people would say to me, "What do you do?" and I'd say, "I run for Borough President." Then when I finally succeeded in1985, and people had become dissatisfied with Ed Koch.

Keep in mind that I and Sutton who had run in '77, and a lot of us Basil Patterson who became a deputy mayor with Ed. We were all for Koch against Cuomo, in a runoff in 1977, but there came a time when we were less than satisfied, and there was a search for somebody to run against Ed Koch. I don't want it to sound like I was drafted, but I did have a judgment to make after running three times for Manhattan Borough President; I going to put it all on the line, and if I lost I'd have zero.

Brian: Here in 2009, now you've probably been hearing or reading in the obituaries, or some of you if you were around then you remember how his legacy has usually been tied to the Crown Heights Riots of 1991 before all other things. In that same 2009 interview, I asked him this. How would you like your mayoralty to be remembered?

David: I often say that The New York Times, which as you know has partial old bits on public figures, and given my age I'm confident that they have one on me. The opening graph will read, David N. Dinkins, born July 10th, 1927 in Trenton, New Jersey, first Black mayor of the city of New York, and then immediately Crown Heights. They are not apt to talk about the fact that we kept libraries open six days a week when we had little money, spent $47 million to do so when this had not occurred in a quarter-century, and there would be mention of Crown Heights.

Brian: Mayor Dinkins here in 2009. Just for the record, he predicted in that answer what the first graph of his New York Times obit would be 11 years ago. Well, here it is. Mr. Dinkins who served in the early 1990s was seen as a compromise selection for voters weary of racial unrest, crime, and fiscal turmoil. The racial harmony he saw remained elusive during his years in office. That's the beginning of that.

That's actually a subhead, so I'll go to the actual first paragraph. David N. Dinkins a barber's son, who became New York City's first Black mayor on the wings of racial harmony, but who was turned out by voters after one term over his handling of racial violence in Crown Heights Brooklyn, so Dinkins predicted correctly, died on Monday night at his home on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. He was 93.

If we're going to think about Mayor Dinkins's place in history, it helps to step back and remember the big picture of the city and the country in those days. That in certain ways lead right to where we are today. Crime was high, but it had been going up for decades. It had gone up and up and up on Mayor Ed Koch's watch, for three terms as it had in cities around the country, and yet, people didn't hold him personally responsible for it in the way I believe they held Mayor Dinkins for it, perhaps because of his race. Dinkins inherited that crime rate and became the first of three mayors to hire William Bratton to be a police leader, and crime started to go down on Dinkins watch.

Racial tensions were also high of course, Ed Koch like Giuliani later, and again, this puts so much on Dinkins in some of these stories, but Koch like Giuliani after Dinkins, was a very polarizing figure along racial lines, especially in his later years as mayor. He had had a lot of black support, as Mayor Dinkins recalled in that clip, but he had lost much of it, and the city and the country were both in a big recession.

Mayor Dinkins in that clip refers to expanding the library hours despite the city's budget woes of the time, and that was true nationally. Two, the budget woes. Remember Bill Clinton's 1992 campaign mantra, which exists to this day. People cite him saying, it's the economy stupid, because it was a very down economy nationally at the end of the '80s start of the '90s, and a high crime period nationally, and voters took it out on George H. W. Bush when he became a one-term president and got defeated in '92, and on David Dinkins when he got defeated and became a one-term mayor in 93.

Then came the federal crime bill in 94 that we're still debating today as a federal government driver of mass incarceration. Exactly as Giuliani was starting out as mayor centering his get tough on crime policies, and meanwhile the economic rebound was taking place in both places as well. Nationally as the cycle kick back up, and in New York.

One way to look at that period is Dinkins and the first President Bush got blamed both of them, for national trends even though they were from different parties. Clinton and Giuliani got credit for the rebound, even though they were and of course, more complicated than that too, but that's one take on David Dinkins mayoralty in context.

Now, tomorrow folks, we'll do a deeper remembrance of Mayor David Dinkins. We're calling up some people who we think will be worthy guests, and we'll do a major segment that we can put together better on a day's notice. For today, those clips and those thoughts, and Mayor David Dinkins rest in peace.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.