NYPD's Chief of Patrol Talks Public Safety, Crime Stats and More

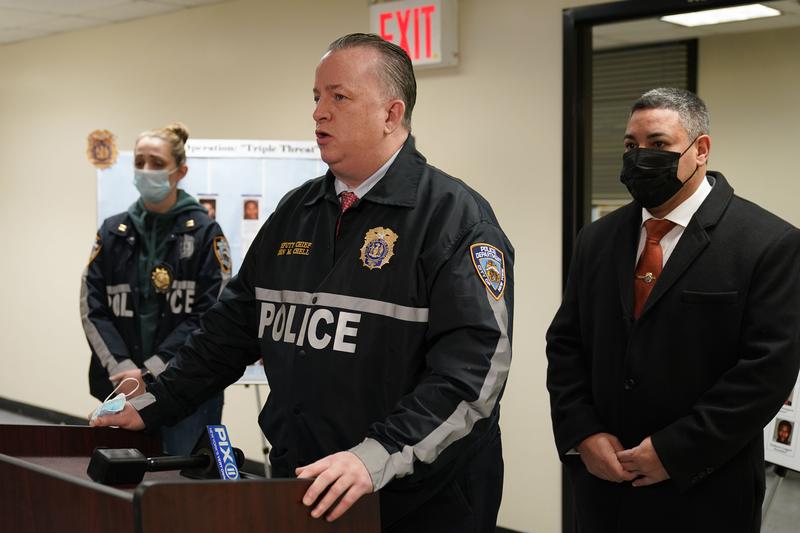

( Seth Wenig / AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone, and happy eclipse day. We got through the earthquake day on Friday and it's on to solar eclipse day today. Someone near where I live posted on a neighborhood website, "Is anyone going out to watch the elipse?" Oops, grammarians everywhere will be thrilled that everyone is so excited about an elipse... At the end of the show today in about an hour and a half, we will share solar eclipse science and safety tips, and stories, very important on the safety level. You can go blind if you don't know what to do during this. It'll be solar eclipse science, safety tips.

We'll take calls from anyone who has experienced a total or near total eclipse of the sun, to give us tips on how to get the most out of the experience. I was in one myself once in my life, and I'll share a little of that. That'll be our last segment today starting in about an hour and a half. We begin this week with one of the top-ranking leaders of the NYPD. We'll talk to Chief of Patrol John Chell about crime in the city, especially crime in the subway system. We'll talk about the murder of Police Officer Jonathan Diller two weeks ago today. Also a controversial fatal shooting by the NYPD a few days later.

We'll talk about Chief Chell's very public criticism on social media of a Daily News columnist, Harry Siegel, in the past week or so. Siegel claims it's part of a naked intimidation campaign by the NYPD as Siegel puts it against journalists who question them. Mayor Adams says it's all free speech. The Mayor said, "The columnist shared his opinion, the NYPD shared theirs." We'll talk about those specifics and the substance of public safety generally in New York City, especially on the subway. Chief Chell, we appreciate you making yourself available. Welcome to WNYC.

Chief Chell: Hey, Brian, how are you?

Brian Lehrer: I'm doing all right. Let me start with my condolences to you and everyone in the NYPD for the death of Officer Diller, just 31 years old, who leaves his wife and a 1-year-old baby. Is there anything you'd like to say first to our listeners about Officer Diller or his loss?

Chief Chell: I was just talking to his partners the other night and recently, we have thousands of officers and sometimes, you don't get to know their back story, what they were about. The more you hear about Detective Diller, the more you realize what a special person he was and what a great family man he was, and almost a mentor to the cops he worked with only with three years in service. Just a tremendous loss to our city. We're still mourning. We still have a job to do. We lost a good one is the message to NYC.

Brian Lehrer: The reporting I've seen says all Officer Diller was doing was investigating a car illegally parked in a bus stop in Queens, and a guy who he told to get out of the car shot him dead. I know the last police officer killings in the city two years ago of Officers Wilbert Mora and Jason Rivera when they were responding to a domestic call. Do both of these incidents tell us something about the nature of risk for a police officer? Because a domestic call or a simple parking violation, these aren't like they were in the middle of a bank robbery or something.

Chief Chell: All the calls, domestic violence or no car stop is routine. When you think about all the 911 calls we respond to, we never know what we're walking into. We could be told what's said to a 911 operator, but at the end of the day, we just don't know what we're walking into. That's the danger and the nature of what we do. For Detective Diller, those two guys in that car, both two-time violent convicted felons, both had guns on them. As far as the driver goes, not only was he a convicted felon, he was arrested for a gun last April and bail was set, and he made bail. In our opinion, he shouldn't have been out on the street, period. If he's not out on the street, then we're not having this conversation.

That's the frustrating part. Detective Diller, look, he fought to his last breath. He was mortally wounded. It's just how he fought to get that gun away from that perpetrator and slide it across the street and save some more lives is just truly sad and remarkable and heroic.

Brian Lehrer: Would you get even more specific about what you would like longer-term incarceration policy to be for people with how many or certain types of felony convictions?

Chief Chell: I think what we suffer from the city is repeat offenders, we call recidivism, to the public repeat offenders. Every community in this city, every single one, has a very small population of criminals that continue to hurt New Yorkers. What we're saying is, "Look, let's deal with them." It's a great story when we could help people, when someone makes a mistake one or two times, and they get rehabilitated, and they make a success out of life. We all love that, second chances. There comes a point in time where repeat offenders, they've forfeited their second chance and third chance, and those are the people that need to come off the street. That would really reduce crime tremendously.

It'll also affect the perception of what New York City sees. A person right now traveling to work does not want to read in a paper how John Smith was locked up 50 times for X and is still out in the community. That gets them upset. That is that perception problem we fight because the crime numbers are the numbers, but how people feel is just so much more powerful.

Brian Lehrer: Well, I read and write and talk to people for a living. I respect that so many men and women in law enforcement put their lives on the line. I say that with humility and respect with the comparative risks of our jobs. Having said that, it is also my job to help hold public agencies accountable and try to assess their performance in the public interest. Let me ask you next about a fatal shooting by police officers that you've been quoted on a few days after the killing of Officer Diller. As the New York Times report said a 19-year-old named Win Rozario, who was in mental distress, called 911 himself seeking help.

The Times says he was fatally shot in his Queens home after officials said he threatened officers with a pair of scissors, and they opened fire. You were quoted representing the NYPD in that Times article saying, "The situation became dangerous right away." The article says the man's brother, who witnessed the shooting, contradicted aspects of the police account saying his mother was restraining her son when he was shot and insisting that the officers had not needed to fire their guns. The brother was, "First of all, it was two police officers against him, and my mother was already holding him. He couldn't really do anything. I don't think a scissors is threatening to two police officers."

Can you respond to that account? Specifically, how does one man with a pair of scissors versus two police officers wind up being shot and killed by an officer's gun?

Chief Chell: I can't go too deep into this story because it's under investigation. What I said that day was it was a fast-moving hectic chaotic situation. It was tragic for everybody involved. We go to these jobs, these calls to mitigate, to de-escalate, to get people help, and sometimes it doesn't work out that way. It's just really goes fast. I wish I can get more into it. A pair of scissors can do you harm. It really can. Like I said, a tragedy for everybody. It's under investigation. Just tragic.

Brian Lehrer: Do you dispute that when Rozario's mother was restraining him?

Chief Chell: Well, again, Brian, I don't want to get too much into who was doing what. Our force investigation team, our internal affairs bureau is looking at every aspect of this, and we'll discuss it then.

Brian Lehrer: All right. Outside of the incident itself once police arrived, to the fact that he called 911 himself seeking help, and this is not your call, not those officers' call. Why were uniformed and armed police officers sent to his home rather than mental health professionals?

Chief Chell: I don't think we have a mechanism where mental health professionals show up to every 911 call. We're the first people that get their call. They're the first cops that get there. They spoke to the brother, and then what happened was what happened. I hear that often. If that ever can be worked out where mental health professionals do show up with our cops, and it de-escalates and gets that person help, that's a good thing.

Brian Lehrer: I see the 102nd precinct where that happened does not yet have the program that some precincts do in which mental health professionals respond with or I'm not sure if sometimes instead of police to a call like that. Do you have reason to believe that if that was in effect that police would have been involved at all? I don't know if the 911 call included any threat of violence.

Chief Chell: I don't know. Again, hindsight would it help? Like I said earlier in the show, every 911 call on the surface might sound routine, might sound the same, but it doesn't work out that way. Would it have helped? I can't say. Like I said, it moves very fast, and then what?

Brian Lehrer: I guess if somebody's calling saying they're in distress as opposed to calling and saying something like, "I'm holding a pair of scissors above my mother, and I might do something to her." If it's just a call for distress, and I don't know what the content of that call was, but it's been described as seeking help. Would it be better as a matter of policy, in your opinion, to have a mental health professional only respond with some of these 911 calls that come from a person themselves asking for help and not threatening violence, no cop?

Chief Chell: To go by themselves, again, you might go there unarmed professionals looking to help de-escalate and get the proper doctors look at this person. The question becomes, what happens when it doesn't work out that way? Then what do the mental health professionals do by themselves? Is there room for discussion to have a collective response and look at something? Sure. We're always looking as a department, as a city, how can we do things better under the banner of keeping people safe, and in this case, getting people the right help.

Brian Lehrer: All right. Now onto crime in the subways and the Harry Siegel Daily News columns. Listeners, we can take a few phone calls for NYPD Chief of Patrol John Chell, especially about public safety in the New York City subway system or otherwise in the city. 212-433-WNYC. 212-433-9692. Call or text. On subway crime, do you want the public to believe the subways are safe like before the pandemic, or do you want the public to believe the subways are a riskier place now where you might get shot or pushed onto the tracks?

Chief Chell: There's two things we discuss when it comes to overall crime. Since the subject is transit now, there are the numbers. The numbers that we are continuously tracked on. Right now transit crime is up slightly. When I say slightly, four crimes from last year based on the crimes that we track. If you just take a walk back to January of this year, crime was up in transit north of 45%. We all know the investment that Commissioner Caban, Mayor Adams, and even Governor Hochul, all invested in putting about 1,000 extra cops a day in transit. It's come down tremendously. It really has. Now, those are the numbers.

We are based on numbers, but people don't care about numbers sometimes, they care about how they feel. Just riding the trains like I do once in a while, last week Commissioner Daughtry, Commissioner Sheppard, the Mayor, and myself, we rode the trains last week till about 12:31 in the morning. The week prior we had that "Chiefs on the Train". I'm sure you saw that. The true measure for us is just talking to all different New Yorkers on the trains, what they feel, what they say, what they think. It was a mixed bag. Some people felt safe, some people didn't feel safe, they wanted more cops. Obviously the homeless and mentally ill are a big topic down in the trains for us.

Crime-wise, it's safe. Perception-wise, we got to just keep at it and give the ridership what they want. What they want, they want to see us. They want us to deal with the homeless and the mentally ill. Then they also don't want to hear about the people we arrest in transit, those repeat offenders, they want to stop reading how they get walking out every single time they're arrested. All this in conjunction with the media, in terms of we just ask the media, and then we'll get into this in a second, just to tell the whole story, you can criticize us, but tell the good, tell the bad, be factual about it, and give the New Yorkers a fair read and how that affects their perception.

Brian Lehrer: There's a narrative we've heard from some city and state officials that the subways are safe. This is the safest big city in America, but because public perception is that they are unsafe, that's why the mayor and the governor are surging NYPD officers and even National Guard troops into the system. Does that mean a lot of what's going on now is security theater to address a public misperception?

Chief Chell: No, we're trying to mitigate, at the end of the day, crime in the subway as it relates to those assaults you see, those pushes, what we call grand larceny, just picking up your pocket or ripping things out of your hands. That's where we're mandated is to get the crime numbers down. We often hear the mayor say without public safety, this city can't prosper, so that's the name of the game. The perception piece is much tougher, we're never going to tell people how to feel.

You got, I think, 4.2 million riders a day, that's a lot of thoughts, a lot of feelings, hard to control that, but if we can give them what they want, like I said earlier in terms of just seeing us out there, seeing token booth clerk, seeing on the train, on the platform, talking to the conductor, help the mentally ill down there, get the help they need, get homeless into a shelter. This is all the collective perception piece that we're trying to fix so hard. At the end of the day, I get to talk about it, Chief Kemper is the Chief of Transit, does a great job down there. We get to talk about, but the cops, the cops are the ones who are doing a 24/7 and trying so hard to get it done.

Brian Lehrer: You say people want to see the cops, do you acknowledge that some people do, some people don't? Maybe you and I, as relatively older white guys, feel reassured when we see a lot of police officers on a subway platform. Maybe somebody in a different demographic doesn't know what to feel, feels possibly a threat. You've heard civil rights leaders and others say, when you're Black in America, you have to fear the cops as well as the robbers. Is it too simplistic when you say people want to see us out there?

Chief Chell: No, I don't think so. Again, I base this on who we physically speak to. I don't know where this narrative-- I understand what you just said, but everyone we've spoken to in the subway, from all walks of life, every community, they want to see us. Some people like-- we have a cop on every train car. Well, that's impossible, but what they're saying is they want to see the police. Like I said, they like to see us by the conductor when the conductor makes an announcement, "Hey, the police are on the platform." They really want to see us by the token booth clerk. If they have any angst, they see us standing there, brings them down a level. I haven't heard anybody say they don't need more cops in trains. They want more cops in trains.

Brian Lehrer: Here's a question about that very thing, I think. John in Manhattan, you're on WNYC with NYPD Chief of Patrol John Shell. Hi, John.

John: Hi. I have a small-- an idea for helping the public feel safe and for the most effective use of resources. What if you had the police positioned on the platform where the conductor's car comes into the train, where the striped sign is? I don't know if people are aware, but there's a striped sign on the platform that shows where the conductor's is going to be lined up when the car is there. If the police were there and the public knew that the police are always there, then the information between the conductor can be relayed to the police officer on the platform if something is happening on the train. Let's say somebody pushes the emergency button and the conductor gets on, is like, what's wrong?

Brian Lehrer: John, let me get a response from Chief Shell. You hear the question. It's about the particular positioning of police officers on platforms to be as quickly responsive as possible if something is going on on the train.

Chief Chell: John is 100% right. What we try to do is have the cops, and he's correct, in the black stripes. That's where the cop knows the conductor stops. How it's supposed to play out is the cops are supposed to be on those black stripes. When the conductor pulls in, "Hello, Mr. Conductor." The conductor makes an announcement on the train that we are on the platform just in case something's happening. What we also as cops do is hold that train for maybe tops a minute and maybe step on the car, physically step on, take a look around, "Good morning. Good evening. How are you?" and step off the train. He's exactly right. That's what we try to do.

Brian Lehrer: Well, one of the calls that we get most often from listeners on the show, and you kind of referred to it a minute ago, is that it looks like NYPD officers are mostly deployed to the platforms and looking for fare evaders. When there are incidents, the worst of the incident, several shootings last year and this year, the Jordan Neely, Daniel Penny incident, regardless of people's opinions on that, they're usually on the trains in the cars, not on the platforms or the mezzanine. Is there too little deployment to the trains themselves?

Chief Chell: No. To your point, which you're correct, the majority of crime, I don't want to give you wrong numbers, but it's a high split. The majority of crimes in transit, number one, happen on the train, number two, happen on the platform. We made some adjustments to that with the surge of 1,000 cops where we're going to put them. I'll give an example. The incident, I think about two weeks ago, 125th Street and Lex, when that man pushed a woman on trains, we had six cops on the platform, six. We were there. We would love to stop every single crime by our presence.

Just like the shooting in Brooklyn about a month ago on Hoyt Street. We weren't on that train, but when those doors opened up, we were right there to apprehend the shooter. Again, in a perfect world, stop every single crime we possibly can. The second best scenario is to grab the person doing it right after it happens, but we'd much rather stop it.

Brian Lehrer: On the focus on fare evaders, the idea that fare evasion is connected to serious violent crime has become a very regular talking point for the NYPD. Is there evidence to suggest a correlation? Do you have data to back up putting as much energy on that as you do?

Chief Chell: Well, look, I think the stats for fare evasion, I think we only arrest about 3%. That includes some people we give a break to. Yes, I'll give you just two weeks ago, and we've had this numerous times, a person in Manhattan jump in a turnstile on parole for murder with a gun. We stopped something that day. We know that is where we stop something. We've recovered numerous firearms at the token booth clerk. We've people who are wanted, people who are wanted on warrants, recidivists. It is powerful. I don't have exact numbers for you, but I can get them for you but it is the first line of defense. That doesn't mean that we don't give people break.

Students, elderly people, we're going to give you a break. We're not doing that. We give what's called a TAB summons, which is a civil enforcement summons. It's not really punitive in terms of your record, if you will. Like I said, only 3% of the TAB summons we write end up in an arrest.

Brian Lehrer: We'll continue in a minute with NYPD Chief of Patrol John Chell. More of your calls and texts, and we will get into his back and forth with Daily News columnist Harry Siegel. Stay with us.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC as we continue with NYPD Chief of Patrol John Chell. I don't want to get too into the weeds about you and Harry Siegel's Daily News column, but he says when you lashed out at him for several reasons, you didn't even address the substance of his column. Which was largely that the NYPD's transit chief and a deputy commissioner said on TV, after a news anchor described an incident of her producer seeing a woman defecate during her subway commute, that they said there's nothing officers can do about people behaving erratically unless they're committing a crime at the moment. Harry Siegel in his column called that nuts. Do you stand by what your colleagues said on that show, or is there more that they can do?

Chief Chell: Look, there's always more we could do, and that's why we're currently looking at our homeless and mentally ill approach in the subway. We do a lot already, but we're always looking to do better to, one, get people help, and number two, again, keep our ridership safe and feeling, feeling safe. The substance of your article, okay, well, if you want to criticize upper management about our policies and things that you don't like that are wrong, by all means, we're fair game. When you talk about substance of an article, I've yet to hear an answer about how the substance of transit crime had anything to do with the cheap shot against our chief of department.

That's where part one issue I take with the article. Number two, you come out with an article that hit the computer, if you will, at five o'clock, a few hours after the burial of Detective Diller. Then it comes out on Easter Sunday, and then you say something in sum and substance, the cops aren't in line with what's going on in transit. Yes, we're going to take exception to that. We really are.

Brian Lehrer: Obviously a horrible tragedy, a horrible murder of Officer Diller. How long after that should journalists not write critical things about NYPD tactics and approaches and strategies? How long should they not criticize, not ask questions?

Chief Chell: Well, I don't have a strong answer for that one, but it certainly shouldn't be the day after on Easter Sunday. That I'm pretty sure of.

Brian Lehrer: At the Mayor's Weekly News Conference last Tuesday, WNYC reporter Elizabeth Kim asked the mayor about the substance of Harry's column regarding people who appear to be homeless or in distress. I don't think she referenced Harry. She put it in her own words, but I think it was along the same lines. She said, "I see the NYPD there, but I don't see them having conversations with homeless people." Here was the heart of the mayor's response. I'm going to play a few seconds of Mayor Adams here.

Mayor Adams: I saw that yesterday, that if the person had no shoes on or they were sitting down, clearly they needed help. The officers were not willing to engage. We need to sit down with Deputy Mayor Williams-Isom and her team and Brian and others. We need to figure out how do we tweak that more, because I would like to see the officers get more engaged just in that initial contact.

Brian Lehrer: It sounds like the mayor is acknowledging the premise of Liz's question and Harry Siegel's column. Do you hear it that way? Are you taking any steps yet to correct what the mayor described there should be done?

Chief Chell: Right. There are some cops that I think we may send out that come to transit for a day to help out over some of those 1,000 cops that maybe aren't used to doing that kind of work. We have to get them more engaged, and we're looking at that, but the Transit Subway Safety Task Force, you call them, that that's their job, they do a lot of removals with the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, they do with some private organizations. Like I said earlier, there's room for improvement, and there's room to always take a look at what we're doing and how can we do it better? If there's anything broken, how do we fix it? Can we do something better? Who's responsible for it? We are currently looking at, as we speak, to address the mentally ill, to get them help, and to make ridership feel safe.

Brian Lehrer: Eddie in Harlem, you're on WNYC with Chief Chell. Hello, Eddie.

Eddie: Hi, Brian. Thanks for taking my call. To your guest, thank you for answering questions. What I wanted to bring up was that yesterday evening, Sunday night, I got off the train around 7:30, 8:00 PM. It's a 2/3, the express stop at 125th. Walking from the platform to the street, I'm not exaggerating, I saw at least three different drug transactions. It's the same folks. I see them all the time. There were officers in the station. I think there were officers on the street, on 126th Street, sitting in their parked vehicle. It makes me angry, frankly, that I see these same folks. I'm sure everyone who lives in the neighborhood sees these same people. They're recognizable to me.

They're always doing these transactions right on the street in public, not particularly sneaky about it. It's obvious they feel like they can act with impunity. There are officers in the vicinity. I don't understand where the mismatch is. I was hoping that you could explain to me what's going on there.

Chief Chell: What block was that you said? I'm sorry, 126th and where?

Eddie: In Harlem? The 125th stop on the 2/3.

Chief Chell: 125 and Lex, I think you're referring to. All right, look, obviously, we don't want any drug dealing on the street. I wrote down the location. The cops, if they're in the car, they should be out of the car. I don't know what they were doing, but they should be out of their car, walking [unintelligible 00:28:04] to give that presence, to not have people doing drug transactions. As far as transit goes, you say, I'm glad you saw the cops down in transit on the platform. I'm happy that you saw what you saw on 126th Street. It seems like an ongoing problem. I'm writing this down as we speak. Again, we're doing everything we can to keep 125 and Lex a safe corner. It's one of our most active transit hubs in the city, and we're trying to address that. [unintelligible 00:28:36] more cops down, like I mentioned earlier, but I'm sad you saw that. I'll take a look at this.

Brian Lehrer: Some of the pushback we're getting in text messages regards police behavior in the subways. One person writes that it's false that police are routinely stationed on the platforms where the conductor's car is. That listener says, "They just don't see it." Another listener writes, "Not my job is what I'm hearing with the sound bites coming out of his mouth." Another one writes, "Police want respect, change their behavior. Cops don't interact with the public. They look like scared and annoyed people with guns." A fair number of people probably are nodding their heads right now when I read those texts.

Chief Chell: Well, our officers aren't scared and annoyed. Not my job, it's all of our jobs here to keep this city safe. I appreciate their opinion, but I'm going to have to respectfully disagree. Like I said earlier, look, in January, crime in transit was 45 plus percent. These cops who were down there making arrests, levels of arrest, we haven't seen in years whether be those token booth clerks on the train taking guns, and they got that number down. Again, these are numbers, but this is our mandate to keep numbers down. Now we're going to have to work on our perception piece and make people feel safer. I appreciate the text. I'm going to have to respectfully disagree with their analogies. Rest assured, the city, this team, this administration is doing everything it can to make the city prosper through public safety.

Brian Lehrer: On making so many arrests as a point of pride, there are people who don't want to go back to the bad old days of crime rates in the 1970s, 1980s. There are people who don't want to go back to the bad old days of mass incarceration. Do you take that into account?

Chief Chell: Absolutely, but we're making arrests because people are breaking a law. How about stop breaking the law? We wouldn't have to make arrests. What the public sees, again, we're talking about transit. They don't want to see people jumping the turnstile. They don't want to see people getting assaulted. We have to make arrests. No, we don't want mass incarceration by no means. We want people to get help. We are a very benevolent city. We want people to get second and sometimes third chances to better themselves, but when it comes to repeat offenders who are causing these issues, that's who has to be removed from our streets because at the end of the day, it keeps the community safe, it keeps the cops safe, and that's we're trying to do.

Brian Lehrer: On your tweeting about Harry Siegel, you wrote for example, "The problem is that besides your flawed reporting is the fact that now we're calling you and your latte friends out on their garbage." The NYPD Twitter derisively nicknamed him in a way that maybe Donald Trump is most famous for these days calling him Deceitful Siegel. My question about that is the motto of the NYPD is courtesy, professionalism and respect. Many people see that kind of tweeting as neither courteous, professional nor respectful. What would your response be?

Chief Chell: Well, we are not a punching bag. We try to stay professional, but we have a platform also and this is no longer a one-way street. I think what people are upset about is they're upset that we're pushing back and protecting our agency and protecting our cops. Our Public Information Deputy Commissioner stands by his analogy. Sometimes with certain people, you have to talk like that. We'd rather not. We'd rather keep it professional. It's funny. I think on a show we did last week, our mayor was criticized maybe a year ago for not letting us speak, and now he's letting us speak, and then we get criticized that way. Which way do we do this? We want to keep it professional. We do have a strong platform, and we're going to push back with things that we don't like.

Brian Lehrer: Well, Siegel says that what you're doing is not just defending yourself against criticism that you think is unfair for the department, but using your power to intimidate journalists into giving you more positive coverage, I guess, by you being snarky and calling people by derisive names. Do you want journalists to be afraid of you?

Chief Chell: Absolutely not. The journalists, the media is a stakeholder in this. We're not trying to intimidate people, but some people have to look in the mirror. Everything they said to me, does it apply to them?

Brian Lehrer: That you're out there getting aggressive with the police watchdog press makes me feel I have to ask you about this. I read that in 2017 a jury awarded $2.5 million in damages to the mother of a man you shot and killed. The reporting was that he was trying to get away after allegedly stealing a car in the middle of that, and you were chasing him, I gather, and you said it was an accident when you fell and your gun went off accidentally, and the department backed you up on that. The jury found that the ballistics report showed you must have been standing, and they awarded $2.5 million in damages from the taxpayers of the city.

With respect, Chief Chell, if NYPD Twitter is calling a journalist deceitful for something he wrote, a jury apparently found you deceitful for fatally shooting somebody and trying to pass it off as an accident. Are you in any position to be throwing those kinds of stones?

Chief Chell: Look, that was a tragic, tragic accident. A district attorney cleared me on this. The communities I've worked for over the years cleared me on this. I've served the city 15, 16 years after that. That was a civil trial, and I'll just leave it at that.

Brian Lehrer: There are those who question why, with that particular blot on your record, Mayor Adams and the commissioner would have given you the honor of being Chief of Patrol. Why, in your opinion, shouldn't that kind of jury finding be disqualifying for a top leadership position?

Chief Chell: Well, I've worked for the city for almost 31 years, and I've worked in all different kinds of communities and worked very hard to support the city and the communities I've served and the cops that work for me. He gave me this job and our team is trying to get crime down in the city so the city can prosper.

Brian Lehrer: I'm going to take one more call before we run out of time. I will say that this is the most frequent question that people are asking on our lines and on text messages. It's Jesse in Sunset Park, you're on WNYC with Chief John Chell.

Jesse: Hi, Brian. Thanks for taking my call. I called a bunch of times. I got to say something. I live in Sunset Park. I use the 9th Avenue train station. This happens all the time. The cops are on the cell phone, the kids are hopping right in front of them. I can only do so much. I pay my fare. I don't beat the fare, but this sort of stonewalling that I'm hearing on this show, the curtains don't match the drapes. I'm in the station the other day, a kid is on a scooter, scoots, bumps into me, hurts me. I'm not a little old lady. I can take it, but hits me. I say to the cop, I say, "Hey, aren't you going to do something?" The cop doesn't even look up from his phone, and he says, "Well, did you get hurt?" That's not the point.

The point is you're there to serve and protect. You got to take care of the people. People behave like garbage in the train and the police do nothing. I know I'm not the only person that's hearing this. Let's say you take a picture of the cop because, "Hey, I want your badge number. I want something to happen to you," nothing happens. Punitive action never happens. What actually happens is the cops get nasty when you do that. I'll tell you something else. If I was a Black guy, it would be a lot worse, and I'd feel a lot of consternation about actually pulling the trigger on that photograph. I think that whoever is talking right now is full of it. You know nothing about the streets. You have never walked the streets. You're a phony. That's what I got to--

Brian Lehrer: Whoa, whoa, Jesse, you know what? I'm going to draw the line there. Well, you can tell him what your experience is. I know you've been commander of several different precincts, so you've been at the neighborhood level. To his point about cops being on their phones and not doing anything, that's the one that's blowing up the board and the text message file.

Chief Chell: Well, what can I say about Jesse? I'll leave it at that. In terms of the phones, yes, listen, cops, are they looking at their phones when they shouldn't be sometimes? Absolutely. I'm not going to-- but there are times-- they have a lot of information on their phones, their whole computer system is on their phones, running names, locations, 911. Their phones are basically their desktop computer in their hands. Not all of that is what people are complaining about. They have to understand what are in those phones, the information they're receiving in real-time, the crime reports they get for a particular train, numerous wanted photos they're constantly looking at to see who-- if they run across someone in the train that's wanted. It's more to it than that.

Brian Lehrer: You want to say anything open mic as we end the segment?

Chief Chell: No, I appreciate the time. It's always a great platform to get our factual message out the best we can and all under trying to keep New York City safe and share our experiences with New Yorkers and hopefully keep doing what we're doing.

Brian Lehrer: Chief John Chell, Chief of Patrol for the NYPD. May everybody who works for you and you yourself stay safe out there. Thank you very much.

Chief Chell: Thank you, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Much more to come.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.