NJ Legal Rights & NYPD's Facial Recognition Technology

( AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein )

[music]

Nancy Solomon: It's the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Welcome back, everybody. I'm Nancy Solomon filling in for Brian today. Last Tuesday when New York governor Kathy Hochul announced a plan to install cameras in subway cars, this somewhat puzzling line from her speech gained lots of attention.

Governor Kathy Hochul: You think big brothers watching you on the subways? You're absolutely right. That is our intent, to get the message out that we are going to be having surveillance of activities on the subway trains.

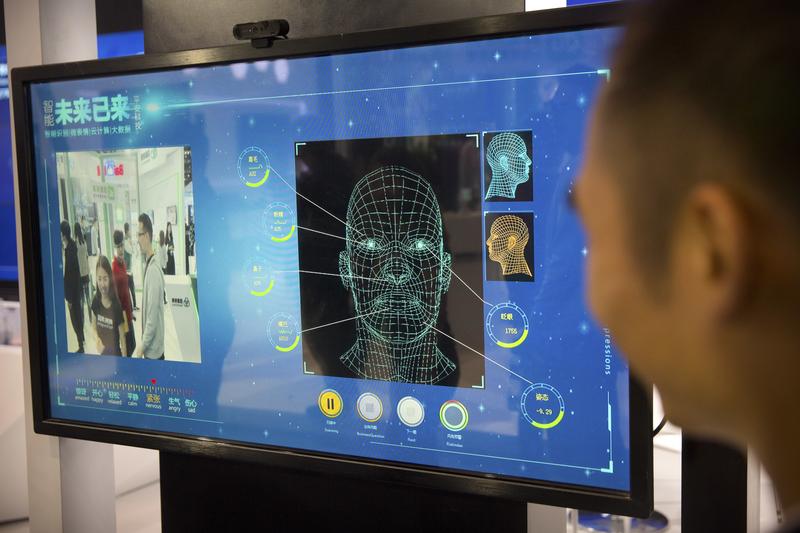

Nancy Solomon: Wow. While cameras and subway cars haven't been installed yet. Hochul is right. Big Brother is already watching. Unlike the Orwellian novel, it's not a 24/7 surveillance through telescreens. Instead, we could potentially be identified with facial recognition, a revolutionary technology that has surfaced in the past 10 years.

Police reform advocates have raised the alarm on this technology saying it can lead to false arrests. One case in Hudson County has grabbed the attention of multiple organizations concerned by the threat to privacy or civil liberties, that facial recognition software poses. Joining me now is Alexander Shalom, the senior supervising attorney and director for Supreme Court Advocacy at the ACLU of New Jersey. Alex, hi.

Alexander Shalom: Hi, Nancy.

Nancy Solomon: According to a CNBC poll or reporting, companies that make facial recognition technology have created databases of faces by collecting images often without people's consent from any source they can access. What can you tell us about where they're getting this database of photos of faces?

Alexander Shalom: The interesting thing about this case, Nancy, is that I can't tell you anything. That's really what the case is about. The case is about the fact that in order to defend himself, a person who was charged because of facial recognition technology wanted to know some of those questions, wanted to know where do they get the database, who's on the candidate list, who's manipulating the data, what is the name of the software? Things as basic as that have not been disclosed to the defendant.

Nancy Solomon: We do know that there are private companies that are selling people's data which includes photos of their face that could come from social media say.

Alexander Shalom: Sure, we know that those are the possible ways that the databases can be formed. What we just don't know in this case is did they only use information from the Department of Motor Vehicles or did they also get things from the Department of Corrections or did they get things from Facebook or did they get thing? They're endless possibilities. All of those things impact the reliability of the technology and to defend oneself in a very serious case it's important to know those answers.

Nancy Solomon: You just mentioned mugshot. We're talking about people obviously who have been previously arrested. How is this being put into use? Why do police officers need facial recognition and how did they use it in conjunction with this database? There used to be a book of mugshots, right? Like how are they using it now in terms of fighting crime?

Alexander Shalom: Again, we have to just infer because the NYPD is being scrupulously silent and not answering the questions that we think we're entitled to have answers to. Our best understanding is that the way that NYPD's facial identification Section, FIS, works is they start with a probe image that's something that was maybe pulled from a surveillance camera or something like that.

They take their probe image that they're trying to identify, but sometimes it has to get edited because probe images work best when their eyes are open, mouth is closed and it's a full frontal shot right of the face. If the head is turned to the side or the mouth is a gap or the eyes are closed, they might Photoshop it a little. At some point, they then take the probe image, maybe edited, analyze certain points and features to create what's called a face print.

It's a mathematical formula, which, again, we don't have access to. They take that and they run it against an unknown database, that will produce a candidate list. Maybe a hundred people who look similar to the probe image, they assign a numerical confidence ratio. This person is a 94 and this person is a 92 and then a technician, again, someone we don't know chooses which image counts as a possible match.

The thing that's so interesting about that, Nancy, though is that the list, that candidate list is going to be filled with false positives because if it's a hundred people, well, 99 of them are not the person in the image and maybe a hundred but at least 99 of them are not the person in image. It's very important for a criminal defendant to find out who's on that list because in that list might be the actual suspect, the actual person who committed the cry.

Nancy Solomon: Listeners, what are your concerns regarding facial recognition technology especially when it's used by law enforcement? Do you work in law enforcement? If so, what can you tell us about the process of using facial recognition to identify perpetrators of crime? Lawyers, what is your take on facial recognition being used as evidence?

Do you work in facial recognition technology for the public or private sector and have something to contribute to the conversation? Call us with your questions at 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Tell me, Alex, how this came onto either your personal radar or the ACL use radar in terms of this potential threat to civil liberties.

Alexander Shalom: This is a case as you said that arises from Hudson County. It was a robbery in West New York and they had an image from a surveillance camera and they brought it to the New Jersey State Police. The state police said, "Well, we can't find any matches. It's not a good enough picture for us to work with."

The West New York Police Department went to the NYPD and said, "Hey, can you find someone?" NYPD ran it through the process I just described, produced a possible match and they went to two different witnesses to the crime and had the possible match whose name is Mr. Arteaga in the photo array. Both people picked Mr. Arteaga out though after some hesitation. One person had gone past him once and then came back.

They picked him out and he was then charged with a crime and he became represented by the Office of the Public Defender in New Jersey. They have a really terrific forensics team there who recognized that this was a novel issue here on how we deal with facial recognition technology. They filed an absolutely terrific brief. They got a court-- First thing they said is, "We need some information." The court said, "We're not going to give it to you."

I can talk about their rationale there because it's really troubling. They then took an appeal and the court agreed to hear the appeal and the office of the public defender reached out to us at the ACLU of New Jersey and our colleagues at the ACLU National and the Innocence Project. We together wrote a brief and some other organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation put together a brief and some of the world's leading experts in misidentification put together a brief because everyone recognizes that this is new technology, but it's decidedly not science.

Rather than being akin to fingerprints, which are at least pseudoscientific, it is more akin to like a sketch artist. It might be helpful, but that doesn't mean it's always reliable and we need certain information to test its reliability. This case that we're litigating now is really about our access to that information.

Nancy Solomon: I'm sorry, that was a very good clear explanation. I appreciate that, Alex. We're going to take a caller who I believe wants to challenge the way that you're describing the technology. We have Dwayne in Manhattan on the line. Dwayne?

Dwayne: Yes. Hi.

Nancy Solomon: Hi.

Dwayne: One of the issues that he brought up was that if there's surveillance photo produced from an investigation, I'm a detective. I've been a detective for years and we've used this technology. That image, it is a photoshop before it's parsed through the facial recognition software.

It is whatever image that is obtained from whatever video surveillance that's around, that image is submitted to FIS, and whatever raw footage it is, the more footage that is available the better. Yes, it does include, it does work best if someone's eyes are able to be seen or something like that. The more footage of that person that's there, the better the software, of course, works, and of course, the better the quality of the image.

Once that hit, if there is a hit that is generated from that image, from whatever other sources that are available, either through previous bookings or other arrest records that maybe the department has access to, the detective receives that hit. That hit, one of the first things they say is this is not probable cause to arrest this person. I want to make that very clear. The regular identification process that has to occur for identifying someone to generate probable cause it still generally relies on a witness. That image has to be presented to a witness with other similar witnesses in that photo array and the rules, especially in the last few years, have been quite stringent as to how that photo is presented.

If that individual is wearing a red shirt and he has an earring or something like that in the ear, then all the other similar images that are presented to the witness have to at best be presented in the same fashion. This is where sometimes Photoshopping is used not with the original photo but with the subsequent photos that are presented to the witness so that all the images appear to be as similar as possible so that the person makes the best so is given the best opportunity to identify who is the perpetrator of the crime.

Nancy Solomon: Okay. Fantastic to have you on the show. I love that. I just love that you called. Alex, do you disagree with what Dwayne is saying?

Alexander Shalom: No. I absolutely appreciate Dwayne coming on and his candor. I just wish we were able to get straight answers like that in the case we're working on which is to say one of the things we wanted to know is was the image manipulated and we were told we were not going to get an answer. The reason we were told that is because the NYPD isn't part of the team in West New York but of course, we don't want to allow police agencies to outsource their responsibilities.

They were asked to do a task and as part of doing a task, they're required to give us certain information and some of that information is the very stuff that Dwayne was talking about. Unfortunately, I don't think Dwayne's answer is going to be admissible in court but it is certainly useful to know that the general policy of the NYPD is to not manipulate those images.

Nancy Solomon: It sounds to me like maybe what detectives do isn't so problematic but it's more at the trial level. The problem is that information about the source of this photo identification is not being shared with defense counsel. Is that the crux of it?

Alexander Shalom: That's what this case is about. It might be that there's some departments that do facial recognition searches in the way Dwayne described which would be less problematic and others where it's more problematic. For example, we don't even know the software that they use in New York. We don't know how often it gets it right, how often it gets it wrong and different agencies use different programs, and that black box where we're depriving defendants and the public of that information is not generally how we approach criminal cases.

We say that because we don't just want to win when we punish the guilty, we also want to ensure trials are fair, we want to prevent innocent people from being convicted. We try and share as much of this information as possible. It's a rule that's been around in American jurisprudence for more than half a century. That's what the fight is about now, getting enough information so that Mr. Arteaga can figure out whether the process used in his case was a fair one and one that led to the right result.

Nancy Solomon: Now, there's a long history with photo arrays and lineups and witness identification. This goes back years long before facial recognition technology. I'm curious how these two things play together because I think it's largely misunderstood that there are problems with photo arrays that are given to a witness and that witness testimony is one of the largest contributors to wrongful convictions. Where is the interplay between the old technology and problems with it, meaning a photo and the new technology?

Alexander Shalom: They're deeply interrelated. Dwayne actually alluded to some of this when he talked about some of the safeguards that have been put in place in recent years to minimize unduly suggestive identification procedures. New Jersey has frankly been at the vanguard of ensuring that eyewitness identification procedures are as reliable as possible which isn't perfectly reliable but is nonetheless an improvement.

Think about this, Nancy. Imagine the facial recognition technology produces a hundred pictures, and they take the one that they want to put in the array and that person clearly is going to look something like the probe image, the suspect. If the other five images that they're asking the witnesses to look at aren't from that list, then they presumably aren't going to look that much like the suspect even if they're wearing the same red shirt that Dwayne talked about or the same earring Dwayne talked about.

In many ways, using facial recognition technology, unless you're being very careful about it, can lead to more suggestive identification procedures because you're putting in one person who looks similar to the suspect and five people who do not. A smarter way, a more reliable way would be to ensure that the filler images, the other five images are also from the facial recognition technology generated list, otherwise, it's natural that the eyewitnesses would gravitate toward the only facial recognition technology generated match.

Nancy Solomon: We're talking about facial recognition technology and the criminal justice system with Alexander Shalom of the ACLU of New Jersey. Alex, why do you think that either the NYPD or the DA's office is so reluctant to share information about these practices surrounding facial recognition?

Alexander Shalom: Because they haven't been told that they have to, frankly, and it's easier for them not to. It's easier for two reasons. One, just a general who wants to go through the effort of sharing things like hit rates and failure rates and false positives and things like that. The other is because it will give defendants ammunition to undermine the technology and anyone who's looked seriously at that technology and as I said there's a whole brief written by our colleagues at the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and a group called Epic that looks really deeply at this technology.

Anyone who looks at the technology understands that it's an art, not a science. I think DAs and police officers would like to present it to juries as if it were a science. I think any information that they have to provide to defendants that undermines that scientific fallacy, they perceive as harmful to their interests.

Nancy Solomon: Okay. We have Brandon from Keyport, New Jersey on the line. Brandon?

Brandon: Hi. Thank you very much for taking my call. I'm a documentary filmmaker. I'm working on a film about a gentleman by the name of Nijeer Parks. Nijeer Parks was wrongfully arrested because of an erroneous facial recognition match. The reason that his name came up in this facial recognition match is because he had been arrested for a crime that happened nearly two decades prior and because his face was in the system he was arrested in a town that he had never visited for a crime that there was ample evidence to demonstrate that it was somebody else. Even though it's a very clear-cut case, it's very clear that he didn't commit the crime. His case has been languishing in the courts for years now.

Nancy Solomon: Is one of the problems have to do with race and the way that facial recognition software works with people of color?

Brandon: Absolutely. In addition to that, because of the way our criminal justice system works, there are more people of color in the system, and probability states that if you are looking at a database that includes more people of color that it's just more likely that a computer will choose one of those people that are in the system.

Nancy Solomon: There was a 2018 study by the MIT media lab researchers about facial analysis algorithms showing that the technology misclassified Black women nearly 35% of the time while nearly always getting it right with white men. There is some research backing up these problems. Alex, is that something that you've looked at or the racial disparities and the way that the recognition software works?

Alexander Shalom: It is and again, Nancy, since we don't know the exact software they're using, we can't be precise but as you point out, the studies have actually shown that generally speaking, facial recognition technology performs worse on people of color, on women and on young people as opposed to white folks, men and older people.

Nancy Solomon: Yes, our producer had pulled up other work by one of your colleagues, Kade Crockford at the ACLU of Massachusetts, the Technology for Liberty project that called facial recognition surveillance technology, Racist and anti-Black. Kade wrote, "Since Black people are more likely to be arrested than white people for minor crimes, their faces and personal data are more likely to be in mugshot databases. Therefore, the use of face recognition technology tied into mugshot databases exacerbates racism in a criminal legal system that already disproportionately polices and criminalizes Black people." Even the use of mugshots could be a problem as well, right?

Alexander Shalom: Absolutely. To be clear, Nancy, no one is suggesting that if you have a suspect, you can't ask a witness whether this is the person using a mugshot. That's not what Kade is talking about. What we're talking about is this mass data flow where you look through hundreds of thousands of pictures to purport to do something and when the data is rigged, as Kade points out, because take New Jersey, for example, where before legalization, Black people were three times as likely as white people to be arrested for simple possession of marijuana.

For just looking at whose face is going to be in the database, even though Black folks and white folks smoke pot at the same rate, Black people's faces are going to be in databases that rely on mugshots at disproportionate rates. That again, Kade's critique, which is spot on, doesn't even take into account the fact that the technology itself fails at a greater rate when dealing with Black people, when dealing with women and when dealing with young people.

Nancy Solomon: What is your hope for this case in Hudson County? I mean, is it that just there'll be more transparency, and or does it take a whack at more controls over the use of the technology?

Alexander Shalom: Well, I think providing transparency provides that whack, which is to say right now, operating in total opacity there's this mythology around facial recognition technology about its accuracy. Once there's more transparency and we can reveal some of the problems with it, then the mythology is stripped away and it becomes just another mediocre law enforcement tool.

That is a really important step in regulating its use. New Jersey has talked, the Attorney General has been in discussions with stakeholders for over a year now about trying to put some limits on facial recognition. One important step in that process is transparency, is ensuring that the people who are impacted by it understand what is being used and how it works.

Nancy Solomon: Let's take another caller. We have Allan in Queens on the line. Hi, Allan.

Allan: Hi. I used to work for a security camera company from 2013 to 2020, and I would recognize my cameras all over the city, or I would know what manufacturer it's from. One of the problems that I see right now is the quality of the pictures itself. It's not as advance as people might think it might be. All the security cameras that you see over town are probably really privately owned and they're maybe 10 years old or 15 years old, or even four years old. Anyway, if you ever take a picture with your smartphone and the megapixels on those cameras are probably 12 megapixel or more.

If you look at what 4K television quality TV is that, it's actually eight-megapixel, 10 80p is two megapixel, and seven 20P is 1.3 megapixel. All the cameras that you see around the city, they're only about two megapixel. If you've ever taken a picture with your phone and you digitally enhance it and zoom in, you'd notice that the picture quality is-- It just gets worse. You can't see anything. Now, imagine what that must be if you have a 2-megapixel camera or 1.3-megapixel camera, anything that you see that's digitally enhanced is just not going to come out very good. That's probably why a lot of times, for facial recognition, it's just not going to be a good hit because the quality's just going to be so low.

Nancy Solomon: Thanks for your call. Allan. Alex, any response to that?

Alexander Shalom: Well, that's exactly what we're worried about. I mean, we know in this case that the quality of the picture was so low that the New Jersey State Police were unable to do anything with it. It begs the question of how was the NYPD, is it because they have a better system? Is it because they have a system that is willing to tolerate more error? Those are the very questions that defendants and the public are really entitled to know.

Nancy Solomon: We'll leave it there. My guest was Alexander Shalom, senior supervising Attorney, and director of Supreme Court Advocacy for the American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey. Thanks so much for coming on the show, Alex.

Alexander Shalom: My pleasure, Nancy. Nice talking to you.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.