The New York Times Investigates 'Failing' Private Hasidic Schools

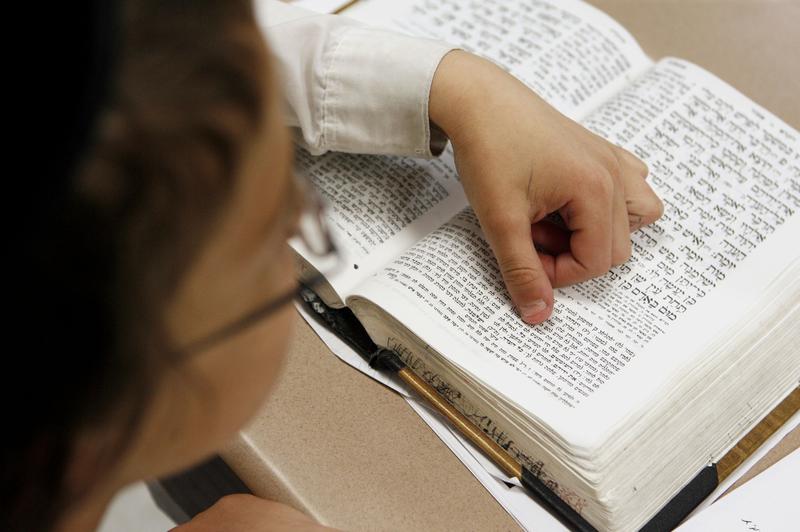

( M. Spencer Green / AP Images )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's the Brian Lehrer show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. We'll begin today by trying to frame some questions implied by the story you're probably been hearing about some Yeshivas in Brooklyn and the lower Hudson Valley, very Orthodox Jewish private schools, that don't teach their students basic academic subjects like Math and English. The New York Times investigation that's been in the news this week concluded that the failure to teach academics is not from mismanagement, it's by design. It's by design, why?

Well, so the students at the schools don't assimilate into mainstream American culture too much. To be clear and so we don't paint with an overly broad brush, the Time story says, this is not happening at all Yeshivas, different denominations of Orthodox Jews have different approaches to education. Some definitely do teach academics as well as religious studies, this is about certain ones in certain very Orthodox or Hasidic Jewish communities that are making certain choices.

Now, the Times article opens, for example, with the story of the central United Talmudic Academy, which agreed to give the standardized New York State reading, Math tests to its students in 2019, more than a thousand students took the tests there and they all failed. They all failed. Every single student failed the standardized New York State math and reading tests at that school.

The Time says students at nearly a dozen other schools run by some Hasidic denominations had similarly dismal scores. For further context, it says only nine schools in New York State in the whole state, Hasidic and everything else,only nine schools in New York State in 2019 had less than 1% of students testing at grade level, all nine were Hasidic schools for boys. The Times also reports on instances of corporal punishment at some of those schools.

Important to this story, the Times notes that the larger group of schools in question more than a hundred schools for boys, where they teach the least academics, plus their networks of schools for girls, where they get a little more, got more than a billion dollars in taxpayer funding in New York over the last four years, but are unaccountable to government oversight, despite apparently being in violation of state law, that requires all students to be given a sound education in basic academic subjects.

The Times article also describes effects of this systemic and purposeful failure to educate as generations of students coming out of these schools, winding up in a cycle of poverty and dependence. Here's another fact that the Times also acknowledges. In the eyes of many of the families who send their kids to these Yeshivas, the schools are not failing at all. They are succeeding, just not according to the standards set by the outside world, the Time says.

Some parents told the Times they know the limits of these schools that teach little math or English and virtually no science or American history, but they enroll their children because they consider secular education unnecessary, or even a distraction from the centrality of religion in their daily lives. I'll add that this whole subject is a matter of debate within the Hasidic community. It's not as simple as some community leaders might portray it as secular world versus Hasidic minorities. The fiercest activism, I think, it's fair to say for adding more academics, comes from members of the community who have come to feel betrayed once they grew up and look back on how they were left uneducated.

Here are some questions we might frame coming from all this. If a community is failing to educate its children in academics by design, but it's for what it sees as the best interests of those children and the best interests of that community, is it anybody else's business to impose different rules on them using state power? 212-433-WNYC, if you want to take a stab at that question.

Another way to put it, if the United States sees itself as a free country, that respects minority rights and respects religious pluralism, and these parents who voluntarily send their kids to these schools and see their communities as succeeding on their own terms, why should the government force them to change? 212-433-9692. On the other hand, if the state sees its obligation to all children, as including a basic education in basic academics, like math and grammar and science and history, and sees a community as systemically educating its children in such a way as to leave many families in poverty for generations, what is the state's obligation to set and enforce some basic academic standards?

Another way to put it, can't the state protect the universal right of children to a Sound basic academic education and still respect the religious freedom of minority religious communities to practice their religions? Are those things really incompatible? 212-433-WNYC? Also, if public funding is involved tax dollars, billion dollars over four years, private schools do get state aid for transportation and other services, does it change the State's obligation in one direction or another?

I'll frame another question, one for conservatives and one for progressives. Imagine this was happening in the same way in a different community. Conservatives who liked to embrace the Hasidim because of their conservative values, in many cases, what if it was a Spanish-speaking community, instead of Yiddish-speaking community that wanted to not teach their kids English?

What if they wanted to teach their kids Mexican history, but not American history, and steep them in Mexican cultural practices while living in America but not in American ones, or what if it was a community of very conservative Muslims? For example, raising their kids with Sharia Law central to the exclusion of math and science and Western history and getting tax dollars to do it, would you be rallying around them in the name of minority rights and the name of religious Liberty? Conversely, progressives, if you celebrate the preservation of other minority cultures, not disappearing through assimilation into the US mainstream, why are you not embracing this example of it?

On any of those questions and you hear, I'm trying to throw these out to many different people constituencies out there from many points of view, we invite anyone's calls. We will also save a few lines, let me say for any Hasidic or other Orthodox Jews who happen to be listening right now, who want to engage on this topic from within not outside the communities, 212-433-WNYC for you and everyone else, heads up if you get bumped by our screener, it's because we're reserving those few lines, so don't be insulted.

It's not about you, it's not about your opinion, we're obviously inviting a diversity of views here, but we're going to save several lines and you may wind up by chance hitting one of those lines for Orthodox listeners, so Orthodox listeners, are you out there today? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692 or tweet @BrianLehrer. You can always tweet @BrianLehrer no limited number of lines there. With us now are the two journalists who reported this story, New York Times education reporter, Eliza Shapiro, and New York Times Metro desk, investigative reporter, Brian Rosenthal. Brian and Eliza, welcome back to WNYC.

Eliza Shapiro: Thanks, Brian.

Brian Rosenthal: Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: We'll get to some of these political morality questions with you when we take calls, but first, as calls are starting to come in and I wish we had a hundred lines, not just 10 for the way the phones are already lighting up. Can you frame what you consider the most new in your reporting, because we've all known for years that certain Hasidic Yeshivas were not educating their students in secular academics very much. It was already a big issue during the de Blasio administration, we talked about it with him and other guests then on this show. Brian, as an investigative reporter, what did you find in your investigation that was most new to you for this story?

Brian Rosenthal: Yes, thanks for that question because there has been a lot of coverage of this issue and we want to acknowledge all of the good reporting that's been done over the last 10 years or so. What we tried to do in our story was to take the deepest look yet, the most comprehensive look, and the most tracking the impact of how it has affected generations of kids. For example, one of the things that we did that nobody has done before is that we actually figured out exactly how many Hasidic boys' schools still are in New York.

We have heard talk about that over the years, but we actually went into the state database, which classifies schools only by religion. It told us what the Jewish schools were of all types and then we spent weeks going through and identifying which of those were Hasidic. That was the basis of us being able to make statements we made about how many students there are, how many schools there are. It was also the basis of the funding work that we did, which has never been done before. We were actually able to identify how much state funding went to each individual school.

We were able to get much more detailed information about funding totals. I did want to clarify, you mentioned the billion dollars over four years. That's actually just for the boys' schools not for the ghost schools. That's actually a significant under account when we were looking at one year, we found 375 million for one year. The other thing I just want to mention--

Brian Lehrer: Wait, on that point, because you got me curious, if a billion dollars of state money went to the boy's schools over four years, did a similar amount go to the girl's schools?

Brian Rosenthal: Yes. Almost exactly the same.

Brian Lehrer: Okay. Just curious from the gender equality standpoint. Go ahead. Did you want to go onto another fact?

Brian Rosenthal: Just a couple of other things that emerged as we really knew for us. The first is test scores as you mentioned. We have heard conversations about the lack of secular education in these schools for years but nobody has really looked at the test score performance. Part of the reason for that is that most of these schools don't administer the tests but in recent years, in just the past few years, some of these scores have started to do so. We were able to obtain and analyze that data. The last thing that was really new for us is something that we were not planning to report about when we started on our story.

We were planning to focus on just the secular education, but as we reported and talked to current and former students and parents and teachers, we heard overwhelmingly from basically every single person that we talk to that there is a culture in many of those schools of frequent corporal punishment being used. We had to include that because we heard over and over again that it was present and that it was really affecting the education in the school.

Brian Lehrer: Eliza, I mentioned in the intro that this is a debate within the community and that Hasidic adults who came through the system are among the core activists, maybe the core activists for change on these fronts. We've had one or two of those on the show during the Mayor de Blasio years. How controversial do you see this topic to be on the inside either before your article this week or in these few days since?

Eliza Shapiro: Yes, that's a great question, Brian. I don't think there is any consensus view within the community. I don't think there is any issue that feels closer to people's hearts and more profound and more serious to people in the community than this one. We were really overwhelmed by the passions on all sides about this issue. We found that there are many, many different shades of opinion on this issue. There's a ton of nuance. There are people who love aspects, parents who love aspects of the schools, but are desperate for their kids to get a better education. They will tutor their children in secret.

They will spend down their savings so that their kids can have a more robust knowledge of English and math. There are former students who we spoke to who listen to the radio in secret, who watch sitcoms and secret to try to teach themselves basic conversational English. Then there are people who feel very strongly that this approach to education produces law-abiding upstanding citizens does a better job of instilling moral values, a significantly better job than the public schools.

Then there are people who feel, as you said, that they had been fundamentally betrayed by their education, that in the culture of the schools and the academics of the schools, everything was reinforced to say, you should not step outside this community. You should not be a part of the secular world and really, you shouldn't even be exposed to the secular world. This is just an issue that I believe is truly roiling this community. It's all coming to a head now with this state board of Regents vote on rules to enforce secular education schools. This article, it feels like an inflection point.

Brian Lehrer: We're 15 minutes into the segment already. Listeners who have joined us since the top, we're talking about the bombshell New York Times, investigative reporting on Hasidic yeshivas, the Jewish religious schools for children, in this case, ones in particular Hasidic communities in New York State dismally failing to educate their students. Mostly boys, and we'll get to the gender differences as we go but we gave the example from the article earlier of all nine schools in New York State in 2019, in which less than 1% of the students passed that grade level on those standardized tests, all nine were Hasidic boys schools.

We're talking to the two journalists who reported this story, New York Times education reporter, Eliza Shapiro, and New York Times Metro desk, investigative reporter, Brian Rosenthal, also talking about the fact that there's a lot of public money going to these schools and raising the question of if these schools are seen as successful on community members, including parents own terms, should the state be getting involved to change them? Let's take a phone call. Ben in Cedarhurst, you're on WNYC. Hi, Ben, thank you very much for calling in.

Ben: Hi, Brian. I just wanted to say that I don't think anything could be enforced from outside the community is going to circle the bandwagons and they will consider themselves under assault. It has to be grassroots. It has to come from within. Also something very offensive in the article, which I read. They called [unintelligible 00:17:18] proselytizing which is very, very false. I'll take the answer off there.

Brian Lehrer: Ben, thank you. Thank you. Well, all right. Ben's gone. Eliza, let me throw his first point to you if activism and I get the implication from his call that he doesn't necessarily support the way these schools are run, but if something's going to change them, it needs to come from the grassroots, from the inside. As a matter of politics, is that happening and as a matter of politics, can it only succeed that way?

Eliza Shapiro: Yes, it's a great question. I've heard that we have heard that in our reporting time, and again, some people will say to us, the activist movement to air the community's issues with education in the outside world, in the secular world, that there is an enormous backlash to it. Some people feel like it's slowing down educational progress. However, the other side of that coin is, we reported, in a fair amount of detail, that the government has decided over and over again from city to the state, not to take action in these schools, not to see what's going on, not to enforce change over the last 10 years, despite repeated urgent warnings about problems.

It's a little bit of a catch-22 here because yes, it is a valid point that it would make most sense for the community to work together to make change, but the other part of that is some people don't want change. That's another debate. The other part of it is that the government so far has not done anything to make change. It's a tricky one.

Brian Lehrer: Let's take another call. Lily in Manhattan. You're on WNYC. Hi, Lily.

Lily: Hi. Hi, Brian. As I'm listening to this and also read the article, of course, I'm absolutely, as a Jew, is mortified by this, especially that my nephew with 12 kids, it's part of the Hasidic group. Also my cousin, I forgot to mention that as well to your screener. The argument in the family has been always you get money from the government, and you run your own show and it is just the way the children are being raised in school, however they're being raised is fine, but the way that they're being educated in school is just mortifying to the family members that why they're doing what they're doing, which is very unjust.

Brian Lehrer: Why do you see those relatives of yours doing what they are doing? They must think it's for the best interest of their children in their community. How would you describe what they say to you?

Lily: Then finance it yourself, the taxpayer's money, or coming in and you are running your own show and you are not going by the law that everybody else has to follow with education. The other point was that my sister and her husband actually came over to America. They're not American, by the way, and took the whole family back to Israel. They're doing the same thing in Israel, which is even freer hand. They don't go to the army, they don't want to work and they can't even work because they don't have the education that requires for getting assimilated to any kind of environment that they live.

Brian Lehrer: Lily, thank you very much for your call. We really appreciate it. Brian, we hear how close this is to that particular caller and how much, by that example, it's a conversation within the community and with people with different points of view. It's interesting that that caller came back to the taxpayer funding question like many people on Twitter are doing right now. I'll give you one example. Let's see. How about this one? Someone writes in Wisconsin v. Yoder, the Supreme court ruled Amish parents didn't have to educate their kids beyond grade school.

Hasidim have the same right, but no right to public money. Why are they getting public money? I'll bet, Brian, that some listeners may be surprised by the taxpayer funding element in this story, $2 billion over the last four years, you say, and people might be surprised not just from a separation of religion and state standpoint, but that any private school system gets that much public support. Why is that the case at all and why at that level?

Brian Rosenthal: Yes. Good question. The reason is that generally speaking, religious education and any private school is not supposed to get public funding, but there are a couple of ways that they do. One is complying with government mandates. For example, our legislature passed a law some number of decades ago that said that all schools in the state need to take attendance every day and keep track of their enrollment.

They decided to extend that law to the private schools that they also needed to keep track of their involvement. That's a government mandate, and the idea is that in order to comply with that government mandate, the private school needs money from the government. These schools receive a bunch of money every year to take attendance. Now there's no real accountability that on the fact that they actually do take attendance but it's not insignificant amount of money that they get. There are many examples of this.

We identified over 50 different funding sources. Many of the examples are not so directly related to providing education. Some of them are things related to administering social services. One of the most interesting funding sources that we looked at was childcare vouchers which is a city program that exists to provide support to low-income families in order to help them obtain childcare.

It turns out that, of citywide, about one-third of the money that is in this childcare voucher program goes directly to Hasidic yeshivas and other providers in Hasidic areas, but mostly Hasidic yeshivas. Basically, what the yeshivas have been able to do legally is label the end of their school day since they usually go till 5:00 PM or 6:00 PM that they label those last couple hours as after-school childcare, and it's in large numbers, tens of thousands of kids that qualify for that. That's a huge funding source. It's over $50 million for just Hasidic boys' schools. There are a lot of different programs like that, that these schools access.

Brian Lehrer: We'll continue in a minute [unintelligible 00:25:27] in Connecticut. We see you you'll be our next caller. Everybody stay with us.

[music]

Brian Lehrer on WNYC. As we continue with New York Times education reporter, Eliza Shapiro, and New York Times Metro desk, investigative reporter, Brian Rosenthal. They are the bylines on the blockbuster story that dropped over the weekend. Their investigation of hundreds of yeshivas in the Hasidic communities, mostly in Brooklyn and the Hudson valley failing to educate their kids in academic subjects, failing by design. The article reports in detail despite getting billions of dollars over the last four years in public funds, [unintelligible 00:26:20] in Connecticut. You're on WNYC. Hi, [unintelligible 00:26:23].

Caller: Hello, Brian. Hi, guys. Thank you for having me. First of all, I'd just like to commend the great work of Eliza and Brian. Secondly, I just want to say that I actually attended one of the schools, one of the yeshivas in Brooklyn. I've never had a single secular education class ever. As far as the broader discussion about having, providing adequate education for children and still maintaining their insular lifestyle, I think it's something that we see with other ultraorthodox communities that they're able to maintain their way of life and still provide adequate education. That's not really an excuse for raising generations of children that are not prepared for the real world.

Brian Lehrer: How do you understand why they do it?

Caller: I'm not sure but I think that over the years, they've just become more and more afraid of the outside world, and they're just convinced that it's a contradiction to their lifestyle, but it's obviously something that's not.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much for your call. I see that [unintelligible 00:27:36] is calling in. He's one of the activists who came out of this system and is now questioning it from the group called [unintelligible 00:27:46]. Let's take [unintelligible 00:27:48] call. [unintelligible 00:27:50] you're on WNYC. Thank you for calling in.

Caller: Thank you so much for having me. I wanted to just briefly follow up on what [unintelligible 00:28:00] said on the question of whether change has to come from within and whether this is going against religious preferences and preservation. I think, look, my own sisters who went to the same to a Yeshiva belonged to the same sector as the one I did. They got a decent education there.

They were split in half, half Jewish, half secular studies yet, and that was okay for them. The same is true for many other ultra-Orthodox yeshivas, just not for Hasidic boys. I think it's just over the years as government looked the other way, I think they just got comfortable chipping away more and more secular education. I think that's why enforcement is necessary. I also have two questions specifically for the reporters to elaborate on.

Brian Lehrer: Before you go to one is, and I'll let you to ask your questions for sure, but just to follow up on what you were just saying. Explain to people who may not understand this piece of it, why this is more severe for the boys than the girls. In some other religious, very religious communities we could name, there's a systemic lack of education for girls. In this case, it's more for boys. Why?

Caller: Right. I think it's a good framing because if it were happening to Hasidic girls, I think fewer people would be tolerating it. To answer your question, the way the Hasidic community works is Hasidic boys are all groomed and seen as destined to be a rabbi or [unintelligible 00:29:35] what they call a learned man. For that, they spend their entire day studying the Torah with the Tanakh and then Halakha which is Jewish law. Meanwhile, the girls, they can't grow up to be rabbis in ultra orthodoxy.

Furthermore, they're also prohibited from studying the Tanakh. Therefore, that combination of both not being prepared to be a rabbi and frankly not being able to study within that men spend almost their entire day studying, They have this chunk of time that they then designate for secular education, so that if the future husband does grow up to become that rabbi that they were prepped for, then the wife is able to provide for the family, especially in the early years of marriage.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you for that. Now you wanted to ask the reporters a couple of questions.

Caller: Yes. Sure. The piece is very thorough. Obviously, it's very long, but despite that, there are some places where it felt like, oh my God, I wish they elaborated. Here are two, one is and one place the report's right that at some point New York City wanted to ask the state for further assistance and guidance.

A state official told the city not to ask for assistance. I'm wondering if they can elaborate on who the players were involved in that incident. The other thing is at some point they described that the city when they were conducting the investigations at one Yeshiva, they saw that the teacher didn't seem to know the students' names. Again, I'm wondering if they can elaborate and talk about what their implication is. Are they saying that this was a charade? The teacher was just hired for the day? What exactly are they suggesting?

Brian Lehrer: Who wants it?

Eliza Shapiro: I can take this not to leave. I think what we've reported is what we've reported and we think the story speaks for itself. We're not going to break any news or identify anyone on the radio show that we didn't identify in the story. I'm sure not to you and I will speak later in the day anyway. I did want to briefly return to what the previous caller said because I think it's a really important point that you asked, Brian, about, why is it that there's so much fear of the secular world and we found that it's gotten in some ways worse in the last few years if there's more fear of the outside world.

One thing I really want to emphasize that we found over and over in our reporting was that the creep of the internet, the ubiquity of the smartphone can feel like an existential threat to Hasidic leaders. We have dozens of school rules that parents need to look over and sign to enroll their children. Almost all of them say you can't have a smartphone, you can't have a computer, you can't access the internet. I do just want to tell people that there is this inflection point about internet access that we believe has led to more restrictive, more conservative views around education in the last decade.

Brian Lehrer: This is the segment of the show where I thought we weren't going to be talking about Facebook and TikTok, but there you go. Now, Naftali, let me ask you while you're on the line, your response to a question, a listener is posing on Twitter. A listener writes, can you ask how they see the problem being "solved from the outside" without changing the actual culture of these specific Hasidic groups, which sounds like colonialism to me and or cultural genocide. I asked this as an ultra-Orthodox Jew who attended. How would you answer to that question to somebody else who comes from your community apparently?

Caller: Sure. I think the law of substantial equivalency has existed since before the Hudson Community settled in New York. It's a law that exists I think in most states in the United States. As it exists in most other countries and as I described earlier, the same way Hasidic girls can do it and other sho Orthodox, even boys can do it in what's called the latest yeshiva or the modern Orthodox world.

It's not a contradiction with religion, it was just a pattern that the community had gotten into and the leaders keep pushing this fearmongering narrative that everyone's out to get them. I think that's the biggest shame that they're turning it into this religious war when it shouldn't be. In fact, there are so many people from within the community who have been sharing us on throughout the years, sharing documents. You think we could do this all purely from the outside? Of course not. We rely so much on parents and graduates and even current students to share information so that we can then use it in our advocacy and to file complaints and so forth.

Brian Lehrer: [unintelligible 00:34:37], thank you for calling in. We appreciate your perspective. We're going to go to another caller now with a student in Yeshiva, calling in anonymously from Brooklyn. Thank you very much for calling, you're on WNYC. Hi there. Since you're calling anonymously, I can't say your name and tell you we're talking to you, but do who I'm talking to? Are you there?

Caller: Hi, Brian, are you talking to me?

Brian Lehrer: Yes, sure.

Caller: Okay. Hi, Brian. Thank you for having this segment. I'm an anonymous caller because I'm a parent of a 16-year-old who is a Hasidic Yeshiva in Brooklyn. I just want to say that take away all of the bells and whistles of all the other issues that people are talking about. The funds, the antisemitism, all of that at the base. My son is 16 years old.

I started advocating for this issue when he was eight or nine, and he is not getting any secular education. At the very base, our children deserve that English and math in a level that they can go forward with if they so choose to, and not doing this, not providing this to them is child abuse and neglect.

Brian Lehrer: Why do you stay in the system if this is how you feel?

Caller: So many different answers to this? It's a really great question, but also really insensitive why do you stay in this system? Many of us who live in this community, we love our community. We want to be here, but that doesn't mean that we have to stay in a place where it's not good and allow others to control us. This is not how our community looked like 50 or a hundred years ago. My great-grandmother grew up in hung Hungary. She had a fluent Hungarian language.

Our parents knew the language of their countries before they came over here. The way that we are pushing down our own beliefs in a way that is not the way it used to be because, oh, we're not allowed to learn English or math because it goes against our religion is absolutely not true. We stay in the system because we love it. Some of us are forced to stay here for fair of losing our families, for fair of losing our children, and yet more of us are forced to keep our children in these neglectful places because of court orders.

Think about that. In New York state judge that should know the rule that should know the basic rule that every child deserves an education is saying, I'm sorry, but your child should not be getting an education, you just keep them in this school.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you. I hear how difficult this is for you and the layers of feeling and experience that you're reflecting. Thank you very much for the courage to call in even anonymously. Eliza, you want to react to that caller at all?

Eliza Shapiro: Yes, I think first of all, really thank the caller for that nuance, thoughtful comment. It reflects so much of our reporting.

We spoke to over 275 people, many of whom are still in the community who have deeply conflicted views about education, about the community, but love so much of the tight-knit structure, the communal structure, the family-oriented structure of the community.

I will say while many of the leaders and PR apparatus and more official spokespeople for the community say, we are good, we don't need to change. I will say there is a significant perhaps minority, but there are a significant number of parents who want to stay, want to be in. Leaving can be just wrenching for people.

It is simply not an option for some people, but people who want to stay and believe their children can grow up to be good community members in the Hasidic community, but that they could also be fully literate in English that they could know math, that they could know science, social studies, civics, and that those two things are fundamentally not in contradiction. That is one of the most important profound points. I think we heard over and over from people in the community. I just want to highlight what the caller just said in that way.

Brian Lehrer: When I ask her with her 16-year-old who she thinks is getting miseducated, why do you stay in the system, I certainly didn't mean to suggest why do you continue to practice your religion. Of course, I was just asking, why do you keep your child in this school? She ultimately landed on not necessarily feeling that she has a choice. We have a tweet from a listener who says, I'm in the community, you can't root for change within the community, there will be harsh retaliations. I'm curious if that was reflected in your reporting.

Eliza Shapiro: This is a really important point. I think the concept, the idea of choice views of the education of the community is a very complex one. I think leaders would say, look at all these parents they're actively choosing their schools. Again, many parents are, and they're really happy, but let me describe what many, dozens of people told us what happened.

If they said, actually I'm going to send my child to a modern orthodoxy Yeshiva, which has more secular instruction, or I'm going to send them to another private school or a public school. Many people said that would mean exile from the community. You are essentially kicked out. In many cases that means your family and friends will no longer have anything to do with you. You can live really on. You're forced to live on your own as an outcast. I think the idea of choice is not as simple as it sounds in the community.

Brian Lehrer: We're almost out of time with New York Times education reporter, Eliza Shapiro, and New York Times Metro desk, investigative reporter, Brian Rosenthal. They wrote that story about the systemic failure to educate in academic subjects in many Hasidic yeshivas in New York State. That it's by design. Before you go, I want to follow up on what our previous caller until raised about the political side of this in terms of the state and city leaders. There's obviously a political story of Hasidic voters mattering in state and local elections because of their numbers. After your story came out, Governor Hochul who of course is running for governor right now basically said guaranteeing a basic education here is not her job. Listen.

Governor Hochul: People understand that this is outside the purview of the governor. There's a regulatory process in place, but the governor's office has nothing to do with this--

Brian Lehrer: Mayor Adams refused to accept your reported findings as in this clip here also from Monday.

Mayor Adams: I'm not concerned about the findings of the article. I want a thorough investigation and an independent review and that's what the city has to do. We're going to look at that.

Brian Lehrer: Brian, what do you make of either of those clips?

Brian Rosenthal: Yes, well, I think what our reporting found is that it's very clear that the Hasidic [unintelligible 00:42:22] have a lot of political influence. We looked at election data as well, it bears out that these communities often do vote as a block and they are a pretty sizeable number here in New York City especially. They can make a difference.

I will say for Mayor Adams who has been friends with the Hasidic community, as he had said for many years, we did think it was notable that he told us that he's committed to finishing a city investigation into the yeshivas, which has been on hold for quite some time and his folk's list and said they want to do a thorough investigation and find out what's really going on. We took that as a hopeful sign that there, there is a commitment on the part of the city to take this seriously and get to the bottom of it.

Brian Lehrer: I'm going to throw in one other call because it's a perspective we haven't gotten yet from a caller. It's Rose in Borough Park. Rose, you're on WNYC, thank you for calling in.

Rose: Yes. I appreciate that you're listening to the other side of the coin. We haven't heard it mostly and we don't get it in the New York Times or any other article. I wouldn't want to tell their name. It's a shame of what they're doing. Just one perspective. I'm the mother of five kids. I had a simple education, basic high school education, and everybody gets that opportunity.

I came from another country. I was an immigrant and I opened up a business at 21 and did excellent and made investments from that and go on from there. My kids went to the most Hasidic yeshiva. My oldest son is a judge in the Jewish community. He learns to be a judge, there's a plenty of opportunity in the Jewish community, but he doesn't have to be that way. He's helping me with my investments.

He's doing all my paperwork. He's perfect in English. That was with the smallest amount of education they had. I have to thank the yeshivas because at that time I was also thinking that maybe they could use a little bit more, let's say they had on the average two hours of basic English and other things, I said they could use maybe three hours, but I wasn't making a big deal because I saw that they were doing well, sorry. I'm very upset because you only presented not only you but everybody else in the world. One side of the coin.

My next son, unfortunately, thank God he's alive and well with a beautiful family. He had leukemia at age 18 and he was not the best student. He was a little bit of a troublemaker, but very talented and very good-looking and very friendly, very charming. He's very popular with people but in studying, he wasn't doing too well. He just didn't want he wasn't-- Anyway, he did graduate basic most Hasidic yeshiva. What do you think? The minute he got married at age 22, 23, he decided he wants to go to college and he had very basic fast high school course again, then went on to Brooklyn College with a lot of other Hasidical, very religious Jewish guy there and graduated in physical therapy.

Brian Lehrer: Rose, let me jump in just for a time. The article seems to document that there's widespread poverty in the community that seems to be linked to the lack of education for most people, despite it sounds like your children doing very well and bless them. Widespread poverty in the community tied to the lack of education that enables them to join the economy. What's your reaction?

Rose: It's not tied to the education, it's the way they want it. It's not tied the education. Definitely. There is a lot of afterschool programs, after marriage programs, 6 months a year. My youngest son went for a one-year course in computers, all computer security analyst doing very well. There are a lot of things you can do. You can be bus drivers, technicians, electricians, million things you can do without education. Okay, you should have an education at least two hours on the average in yeshiva, which you get, an hour and a half, two hours. I'm not saying, you do get that. You have the basic and they all know the English perfect language. I had a very high education and it didn't help me anything.

Brian Lehrer: You heard the stats that less than 1% in many of the schools pass the state math and reading scores at grade level. Maybe they're not getting it, but--

Rose: Even if they don't pass that, they can do very well. Even if they don't, it's up to them to pass it. Even if they don't pass, how come my son went Yeshiva all the way. They take a short course in high school and everything pass everything, graduated downstate medical center is a top physical therapist in very high demand, doing a beautiful living. What is that? With the basic Hasidic education, if you want, there is a way. Those who live of the government, they wanted that way. You need to have jobs presented to them.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much, Rose. I appreciate it. Eliza, what would you say to any of that?

Eliza Shapiro: I would say these are all really valid points that we are listening to and we have heard, we absolutely encourage anyone who wants to add on to our reporting and talk more about this to email us. We want to talk more and I do think there is, as we said, a range of views in the community about the purpose of education, and how solid the education is. That is an extremely legitimate value viewpoint that we have also heard time and again, in our reporting

Brian Lehrer: Eliza Shapiro and Brian-- Go ahead, Brian.

Brian Rosenthal: I was just going to add real quick that we've certainly heard stories about people who have graduated from Hasidic boys schools and gone on to be very successful. A lot of them had extra help. They had parents who paid for their tutoring outside of school or things like that. We've definitely heard the stories, but for us, the numbers don't lie. You look at things like the poverty rate, which is the highest in the entire state, in some cases, 75% plus living in poverty. That tells something about the majority of people. That's one of the things that we wanted to focus on as well.

Brian Lehrer: Brian Rosenthal and Eliza Shapiro from the Times. Thanks a lot for coming on.

Eliza Shapiro: Thank you.

Brian Rosenthal: Thank you.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.