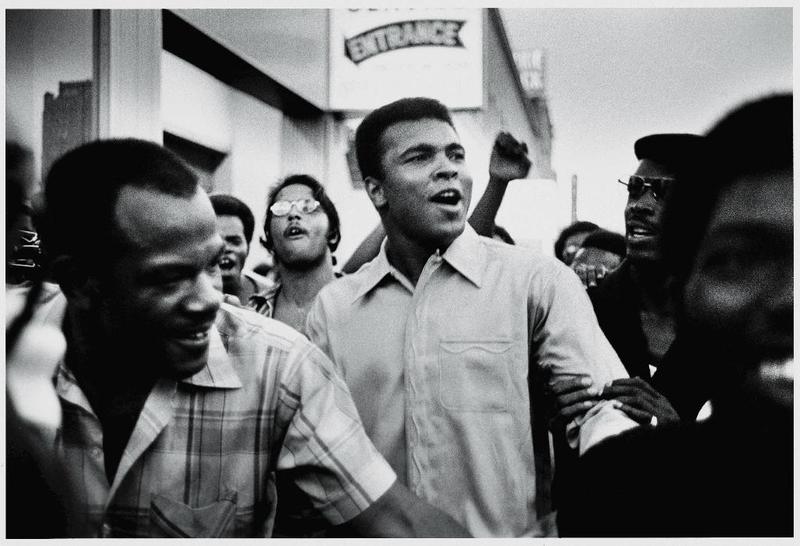

Muhammad Ali, via Ken Burns and Rasheda Ali

( Credit: David Fenton/Archive Photos/Getty Images )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer at WNYC. It's been five years now since Muhammad Ali died, and by the time he passed in 2016, the three-time heavyweight boxing champion was, of course, a beloved American icon but it always wasn't the case. Back in the 1960s after winning the Olympic gold medal, as a light heavyweight in Rome, Ali then known as Cassius Clay, was a celebrity until he converted to Islam and then became a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. At that point in history, he was sometimes known as the most hated man in America.

Documentary filmmaker Ken Burns explores the life of Ali and America's complicated relationship with the athlete in a new four-part documentary titled Muhammad Ali, which will air on PBS four consecutive nights beginning on Sunday, 8:00 to 10:00 PM Eastern time each night. It's co-directed by Ken's daughter Sarah Burns and her husband, David McMahon. Ken Burns joins me now and also joining us is Rasheda Ali, daughter of Muhammad Ali. Rashida, welcome to WNYC and Ken, welcome back.

Ken Burns: Thank you.

Rasheda Ali: Hi, thanks for having me.

Brian Lehrer: We'll hear some clips in a minute but Ken, take us back to the humble beginnings of Muhammad Ali. He was born in segregated Jim Crow, Louisville, Kentucky as Cassius Clay. For the uninitiated, what was his early life like?

Ken Burns: Well, it's an interesting mixture. It's of course, for any Black person living in America a challenging thing, particularly in Jim Crow, segregated Louisville. He has to look through the chain-link fence at the amusement park that's there only for white kids, but he lives also in a middle-class neighborhood, a Black neighborhood called the West End on Grand Avenue. A loving mother, a complicated father who is a raised man who is bitter at the fact that his skin color keeps him from being the painter that he feels he is, the artist he is and he ends up painting signs.

He is, of course, a young boy, not too much younger than Emmett Till when he is kidnapped and tortured and brutally murdered. His mother had the incredible courage to leave a open casket, which was photographed by Jet Magazine, and every Black person in America and many other people saw this unspeakable torture. It had a huge influence on him. Then, as you mentioned, when he wins golden in Rome in 1960, he comes back a hero, and the town itself embraces him to some extent, a group of businessmen, white businessmen, form a sponsoring group that protects him from the mob connections that seem to influence people.

He's getting it in lots of different ways and this is the push me pull you experienced for most Black Americans. This is a story about freedom and courage and love. The love is obvious at the end of the-- The courage is standing up to the draft and saying he could face machine gun fire that day if that was necessary to not go against his faith, something that we Americans took as a political, not a religious statement. We made him the enemy of the state, but it's also a religious journey, and that his faith, a fluid and evolving thing provides him a foundation to understand and deal with all of the contradictions of life for a Black person in the United States, which is a conundrum for the 402 years since 1619.

That they've had to try to negotiate this complicated country.

Brian Lehrer: As we learn in the documentary, Ali in Cassius Clay stumbled on to boxing by accident. Rasheda, do you want to tell the story about how your dad discovered boxing?

Rasheda Ali: [laughs] I would love to. First, thanks for having me on. Hi, Ken. How are you?

Ken Burns: Hi, Rasheda.

Rasheda Ali: Good to hear you again. The stolen bike moment is a pivotal part of my dad's life. Obviously, he and my uncle Rahman, his brother Rudy at the time. They shared a red Schwinn bike and back then, that was like the holy grail of bikes and everybody wanted this bike. My grandparents bought their sons this bike to share and they went to one of those local fairs in Louisville and they parked it and they enjoyed the fare and it started raining. They came back to retrieve their bike and it was gone. Naturally, my dad was upset and my uncle, Rahman, was upset about the bike being gone. He was just prepared to just fight whoever stole his bike.

Clearly as a young boy, of course, he started to ask around the locals. Hey, have you seen my bike or whatever? He stumbled across a boxing gym, that police officer Joe Martin was running in the basement. Once he stumbled upon this gym, he was intrigued by what he saw. He saw all different races of boys in this gym all trying to do the same thing. They're all trying to boxing. I guess Joe Martin said, "Hey, if you want to beat up the guy that stole your bike, you should learn how to box." My dad gave it a shot and it was one of those moments where he really didn't know what he wanted. He was a little kid, but he was like, "This is really a cool sport."

Of course, we know that the rest is history but the important pivotal point of the story is when you run upon a stolen bike moment, you have to look back and say, "What am I going to do?" You're going to make lots of choices. You can go out and commit all kinds of crimes in that situation and try to get your bike back or you can turn lemons to lemonade and try to, hey, evolve into a respectable person and make this moment turn into something very special. That's what my dad did. Who knows what would have taken place if he didn't have that stolen bike moment.

Again, it was one of those situations where my dad always took a situation that was sometimes uncomfortable or bitter and he turned it into something that was positive. It's really interesting to see throughout the film is that he tends to have a lot of stolen bike moments throughout his whole entire life. My dad always took things into stride, he was always positive. He was always thinking of the future, he was transcendental in his thinking for sure, because he was always thinking about other people. In all of his journeys, you'll see he's never a selfish person. Especially growing up in a racially divided country, he was always thinking, how could I make my people free or how can I make our struggles a lot better?

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we don't have unlimited time and there's a lot we want to hear from Ken Burns and Rasheda Ali.

Rasheda Ali: Of course.

Brian Lehrer: We'll play some clips from the four-part PBS documentary, which starts Sunday night, but we could take a few phone calls because I think some of you out there were really influenced by Muhammad Ali. Muhammad Ali inspired or influenced you, in some way whether it was religiously or any other way. 646-435-7280, if you think you're one of those people. 646-435-7280 and we'll try to get a couple of you on. One major turning point in Muhammad Ali's life was when he joined the Nation of Islam and changed his name.

Let's take a listen to a clip from the documentary where Ali is answering questions from reporters about that.

[plays video]

Reporter: Why do you insist on being called Muhammad Ali now?

Muhammad Ali: That's the name given to me by my leader and teacher, the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, that's the original name. That's a Black man name. Cassius Clay was my slave name. I'm no longer a slave.

Reporter: What does it mean?

Muhammad Ali: Muhammad means worthy of all praises and Ali means most high.

Reporter: Do you intend to fight under that name?

Muhammad Ali: Yes, sir. I want to be called by that name. I write autographs with that name. I want to be known all over the world with that name, especially throughout Asia and Africa, because that's the names of our people [unintelligible 00:08:52] home.

Brian Lehrer: The backlash to that name change was swift and brutal. Ken, that's such a classic clip, want to talk about how the public reacted?

Ken Burns: Yes, not very well.

[laughter]

Ken Burns: The first inkling is of course, that many of the competitors against him refused to change the name, taunt him with Cassius Clay. Howard Cosell, who later became a champion is reluctant at first to go along with the name change. It's so interesting that our celebrity culture is filled with people who have different names but if a Black man chooses to do this, it's a different kind of animal here. It's a different treatment that takes place. Even four or five years later, you'll see newspaper clippings where Muhammad Ali is convicted of refusing induction into the draft or sentenced for that to $10,000 fine and five years in jail.

The headlines are still saying, Clay. There's a resistance to a Black person having their own mind, their own desires, their own arc of their life, of being free. At the heart of this, it's a story about freedom, which is an incredibly difficult thing to achieve to escape the specific gravity of the mistreatment that African-Americans have been subjected to from the beginning, as I said. Yes, this name change, I always say strike two. Strike one was the braggadocio stuff. He wasn't behaving the way athletes were supposed to behave and certainly the way a Black athlete was supposed to behave. Then of course the strike three is refusing induction into the draft, that makes him that reviled figure, Brian, that you mentioned.

Brian Lehrer: Rose in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hi, Rose. Rose, we got you. You grew up in Louisville.

Rose: Yes, and went to a college there called Spalding University. They have now put a red Schwinn bike up on the front of their gym building as a memorial to him. It's a really cool thing to see. The other thing I wanted to say was that I met Muhammad Ali once at a jazz club. I'm not sure if it's still exists, but it was called Joe's Palm Room. This was after he had converted to Islam, but sometimes he would show up there and just meet and greet people. I just remember that his hand was enormous when I shook his hand. Anyway, I have some great memories of him.

Brian Lehrer: Rose, thank you. Rasheda, what are you thinking?

Rasheda Ali: [chuckles] I smile because daddy just really loved being Muhammad Ali. He loved people. He loved to somehow connect with people. I've been with daddy so many times, and we'd be going to this event and that event. One time we were here in New York and we were going to the airport and there was a swarm of people that's not letting him get into his limo and my dad loved it. His manager was like, "Get in the car, get in the car." We jumped in the car and was off. There was a man running down the street after the limo saying, "Muhammad, wait, Muhammad, wait." Daddy turned to the limo driver and said, "Stop, stop, stop the car." The limo said, "Well, we got to get--" He said, "Stop the car."

Guy stopped. No one's going to say no to my dad.

He stopped. My dad got out of the limo and he greeted the guy, signed an autograph for him, then got back in the car and we were off. Again, my dad never said no to an autograph or a photo and he felt that every single person that wanted his autograph, whether they wanted to sell it or not, it was a blessing. That's how he treated all of his fans and all of his admirers because of what had happened to him with his idol, Sugar Ray Robinson, who didn't have time for him at the time he was an Olympic hopeful, and Sugar Ray just shunned him off and it bothered my dad. Since that moment, he never wanted to treat a fan like the way Sugar Ray Robinson treated him because he admired Sugar Ray so much.

Brian Lehrer: I want to jump ahead to the famous Ali Frazier fight, Joe Frazier, early '70s leading up to the fight. We're going to listen to a clip from episode three of the documentary. First, we'll hear just a little bit of Ali at a press conference talking about Joe Frazier, kind of talking smack. Then we'll hear the voice of author, Todd Boyd.

Muhammad Ali: Joe Frazier is so ugly. His face should be donated to the bureau of wildlife.

[laughter]

Todd Boyd: Ali is making the jokes that racist white people would make about a Black person's appearance. He's making jokes about his lack of intelligence. The ultimate conscious Black guy is engaging in banter that is basically playing to the side of the racist.

Brian Lehrer: Boyd would go on to say, "I think the way he played Joe Frazier was reflective of the dark side of Muhammad Ali. He could be very cruel." Ken, talk about this side and why do you think he did or said things like that?

Ken Burns: Well, I can't get into his own motivation it's just reprehensible behavior. Todd goes on in that bite to say, "I just think in this instance he used his powers for evil instead of good." I just suddenly-- There was an aha moment for me in the editing room where I read, this is a super hero with larger than life strengths and larger than life flaws. He set up each fight as a dynamic, its own drama. I've called the most important fights the collected works of William Shakespeare.

You just cannot believe what takes place in the first list and or that first Frasier or the others, but he set it up as a drama as just the king of promotion and hype and all of that. Unfortunately, as he assumed the mantle of being a spokesman for the oppressed of the world, as you heard in the previous clip, he's talking about the people in Africa and Asia back home, he says, and he is waking them up and they are realizing he is someone who is speaking for them.

He's also trying to set up these dynamics in which Frazier is the preferred candidate of the white people, which turns out to be because of the way he treats him or many white people, certainly not me. Then he says these intemperate things and he realizes it. That his infidelity, his abandonment much earlier of Malcolm X before Malcolm X murder by members of the Nation of Islam are all things, the deep, deep regrets that he had.

He tried at the end of his life to atone for them to apologize to Joe Frazier. It's a feature that is throughout our film and it is difficult, complicated. You wince at a few instances of it particularly with regard to Joe Frazier, because Todd is absolutely right. He is using the language of Jim Crow about Black people when he is in fact, as Todd says, the most conscious of Black people.

Brian Lehrer: Ken Burns, I know you after go. Muhammad Ali's daughter, Rasheda Ali is going to stay with us for our last few minutes. Ken, congratulations on another epic that looks at all Americans through the lens of one person or one sport, and thanks for coming on as always.

Ken Burns: It's been my pleasure, Brian. Thank you. You're in good hands.

Brian Lehrer: [laughs] I know. Rasheda, you said in the documentary that boxing was such a small part of who your father was. Can you talk more about that and if that's how he saw himself?

Rasheda Ali: Yes, absolutely. I mentioned boxing as small part of my dad because, there's a clip in the film that was just so well done where, and I never saw this clip again. It was really, really refreshing. There was a part of my dad's life in his career where he was delving into his new religion. He said, "I don't like boxing anymore. I don't know what I'm going to do." One of the journalists asks him, "What do you want to do?" He says, "I don't know." He says, "What I want to do with my life. I just want freedom like other Black people want." He says, "God put me here to do something I don't know what that is, but I know, God has put me here to do something."

He got it. He really understood what his journey was because even though he didn't know what he was going to do from boxing, he knew he was going to do great things. From his boxing career, he wore many hats. He was a civil rights activist. He was certainly a father and he was a husband and he was a great brother and he was an amazing friend. He was an ambassador of peace. He decided to put his name on a lot of causes that meant really a great deal for him. Again, there were lots of global causes that he traveled all over the globe, even after he retired from boxing. He saved hostages from Iraq.

He saved a man from jumping from a, whatever, five-story building in Los Angeles because he lived in LA and he found out about this gentleman who had had mental illness. I believe he was a member of the military and he was going into his life and my dad jumped at the opportunity to try to help him and he did. He got him the psychiatric help he needed. Again, there were so many other moments like this where my dad lent his name. He tried to help Hurricane Carter who was incarcerated wrongfully.

Brian Lehrer: Another boxer.

Rasheda Ali: Another boxer he tried to help. Again, he created the Muhammad Ali Act with Senator McCain, where he was really trying to protect boxers from the abuse and the exploitation from either it's a manager or a promoter, he was trying to help boxers. What he was afraid of was he didn't want to end up like Sonny Liston and as so many other boxers who ended up and dying broke. Again, he used and lent his name for causes that would help so many different people and that's why I said he was bigger than boxing.

Brian Lehrer: That's unfortunately where we have to leave at. This went by so quickly and my apologies to other callers who we couldn't get on with your memories and why you were inspired by or times you met Muhammad Ali. Maybe we'll just do a follow-up call in one day. Muhammad Ali's daughter, Rasheda Ali, so gracious to be with us in support of the new Ken Burns documentary, which premier Sunday night on PBS. Rasheda, thank you so much. Pleasure.

Rasheda Ali: Thank you so much for having me.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.