Your Small Patch of Grass and the Amazon Rainforest

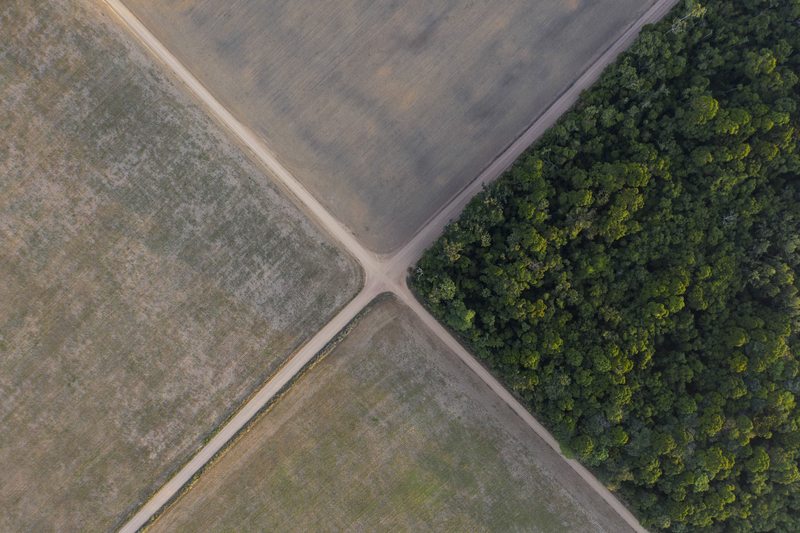

( Leo Correa, file / AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. Now we'll talk to an interesting environmental reporter from Vox who's got two very different almost opposite things for us today about some very small patches of green, and quite the opposite, about the Amazon rainforest. One is about Lula's election victory in Brazil and what that means for the Amazon, the other is about even what you might call a small patch of grass can be vitally important to ecosystems and our quality of life, will explain. With me now is Benji Jones, senior environmental reporter at Vox, who I understand is joining us from Berlin today. Hi, Benji. Welcome to WNYC how is the weather in Berlin?

Benji Jones: Hi, Brian. Good to be here. It's chilly in gray, but otherwise not too bad.

Brian Lehrer: You have an environmental scoop for us from Berlin or are you there for other reasons?

Benji Jones: I'm working on it but I hope so.

Brian Lehrer: Okay, eventually. Let me start with your story last week, your most recent story on Vox called, The surprising value of a small patch of grass. There is a patch of grass you introduce us to in the story called The Bell bowl prairie. Tell everybody, what is The Bell Bowl Prairie and what is it symbolic of in a larger sense?

Benji Jones: It's this little bit of grassland literally like a patch of grass. It's about an hour and a half northwest of Chicago right nearby one of Illinois' largest airports called the Chicago Rockford International Airport. It's a major cargo hub, it services UPS and Amazon. It's this little bit of grassland in a very urban environment and it's home to-- It has a surprising amount of life that lives there at home to a large number of pollinators.

They found an endangered Bumblebee there last year and so what really intrigued me about this story is that you have this little green space in the middle of an urban environment not far from one of the biggest cities in the country and yet, there is life living here and environmental advocates really want to protect it.

Brian Lehrer: The Chicago Rockford International Airport wants to expand and therefore, destroy The Bell Bowl Prairie, right?

Benji Jones: That's right. They are, like many airports that are in the cargo business, expanding pretty rapidly and they want to build a road through the prairie that would cut through the middle of the prairie, eating away a significant portion of what remains. I should just mention that this is a really small bit of land already, it's just about 15 acres or about a few city blocks so they're suggesting or they're planning to build a road that would bisect it and break it up even more.

Brian Lehrer: Even the word prairie is going to make this sound like something that's far away and remote to most of our greater New York City area listeners. Make this universal for us because you write that if Bell Bowl Prairie symbolizes anything, it's the tiny habitats, often hidden in plain sight, have unexpectedly large benefits and they're worth fighting for. There's all kinds of tiny habitats and all kinds of

[crosstalk]

Benji Jones: Exactly. Yes, that's right. There are lots of examples in New York but I will just say prairies we don't think of in the same way that we think of the Amazon forest, which we'll talk about later, and other environments that maybe are more charismatic and exciting. I'm from Iowa, which used to be largely covered in Prairie, Illinois is the same.

Although these just look like grass, just growing like you might see in your yard, they're actually incredibly diverse habitats that have incredibly rich assemblages of life. In fact, the record for the most number of plants in a small area is actually from a small bit of prairie in Missouri. They're surprisingly biodiversity is prairies, even though you might not think so but you're totally right. It doesn't just mean it- It's not just the small patches of grass that are important, it's also the small bits of forests, the small bits of Tundra, and so forth.

We tend to think of big habitats being what's worth saving, again, using the Amazon as an example or the Boreal forests of Canada but in reality, these small habitats often play an outsized role in their environment, because they're the little that's left and so when birds are traveling through or insect pollinators that we all depend on are flying around, they need these spaces as stopover sites or as the last refuges for their lives basically.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, help us report the story or tell us your own story. Benji's article on Vox is called The surprising value of a small patch of grass and the subhead is to save more nature think small. Who has a story like this in your own life or your own neighborhood? Give us a call 212-433-WNYC with a little local small patch Show and Tell if you've got something for us. Call us about a patch of grass that you love, though I will say NIMBY rules apply. This can't be about your own backyard but do you get it? Tell us why you love whatever this small patch of nature is and what can be found there.

Flowers, bees, bushes, cute animals, amazing views, nice smells. Was there a fight that you were involved in to preserve it? Help us just start to end our intense election week here by talking about something nice, a small patch of grass, a small patch of something green, and why it's important in the ecosystem around you but with a political overtone. If there is one, like in Benji's story about what's happening out there near the airport in Chicago, and as your calls are coming in, where you can tweet us @BrianLehrer, let's shift over to your story titled, What Lula's stunning victory means for the imperiled Amazon rainforest.

I want to start with the fact that you gathered a bunch of data in terms of the deforestation that occurred during Lula's original time in office 2003 to 2011, versus Bolsonaro the right-wing president who Lula just defeated, who was president for the last three years so can you paint a picture for our listeners in terms of how much of the Amazon was lost under each leader?

Benji Jones: Yes, I would say one of the most important things that environmental advocates talk about when you're trying to understand what Lula means for the future of the Amazon is looking back at his track record. Lula served two terms between 2003 and 2011. During that period, deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, so by about three-fourths, and so it's a very significant decline in deforestation meaning less deforestation.

If you contrast that with what's happened under Bolsonaro, who came into power at the start of 2019, you saw basically the reverse of that. After this fall of deforestation under Lula, you saw an increase of about 50% compared to the last three years, and an area about the size of the country of Belgium that has been lost in the Amazon so a pretty stark reversal of the progress made in the Lula administration.

Brian Lehrer: How does Lula plan on reversing the damage that has been done to the Amazon, which you write has lost 17% of its acreage or can he only stop future deforestation?

Benji Jones: That's a great question. Everyone's trying to figure out like, what can Lula actually do at this point. When he was in office before, he used existing legislation to enforce monitoring of forest loss using satellite imageries, and people on the ground, levying fines against people who are cutting down the forest because Brazil does have laws that prevent illegal deforestation that have helped in the past.

The challenge that he's going to face coming into office at the start of 2023 is that, to pass new legislation requires Congress to work in his favor, and right now, Congress is very conservative and has very strong ties to the agribusiness industry, which is largely responsible for deforestation so far. He's going to face headwinds, but there is a fair amount that he can do as president, one thing is that he's going to have more money to play with. Norway and Germany have invested a lot of money into Amazon conservation, but in 2019, they paused their donations because of what Bolsonaro was doing and now they have suggested that they're going to start funding the Amazon again.

Lula will have more money than Bolsonaro did for conservation and he's also got a pretty strong team, including Marina Silva, who is a very prominent environmental advocate who's endorsed him as a candidate. I think that he's going to have some things you can do, but he's definitely going to face headwinds and I think we should not expect deforestation to just stop overnight. It's going to take a long time. Bolsonaro dismantled a lot of the environmental protection, so there's a lot of cleanup to do as a first step.

Brian Lehrer: How do you feel, as a reporter who covers the environment, about that kind of contrast between your last two articles? You are writing on the one hand that The surprising value of a small patch of grass to set your headline and then in your other, most recent article about the Amazon rainforest, which could lose land the size of the country of Belgium and still be the Amazon rainforest. The scope of what matters environmentally, it's just astronomical.

Benji Jones: It's a great question. I like the example of the small patch of grass because I think for many people, especially those who are in the US, like myself, the Amazon is very far away, you think of it as this distant, pristine rainforest. It's hard to really grasp the value of it if you're not part of the Amazon community living nearby, whereas these small patches of habitat are things that we can all relate to. I have them near my parent's house in Iowa, they're near my apartment in New York, everyone has some example of a small patch of habitat.

That means that they have exposure to nature that they might not be able to get unless they go on expeditions to various parts of the world. I think that the small patches have a ton of value for exposure to the importance of biodiversity into life but the Amazon it's a little bit farther away but obviously, like when you think about the global scale, especially from a climate perspective, there's so much carbon stored in the Amazon. It is very, very important to conserve these big swaths of habitat as well.

Brian Lehrer: Let's take a small patch of green story from Divine in the Bronx. Divine, you're on WNYC. Hi, there.

Divine: Hey. I'm Divine. In the Bronx, they took over four block acre. FedEx took over four block acre. We had a nice forest, we had fowl in the forest, we had groundhogs, we had the Red Robins and the Blue Jays was topped by during the summer. Since FedEx came, that's gone but right across the water from us, we still have a nice field that they made a soccer field but it still has a good amount of world life that keeps coming but not like it used to be. We used to have swans, we used to have ducks. We have nothing over here in the Bronx anymore.

Brian Lehrer: Divine, thank you very much. Well, there's an example of the battle. The ongoing encroaching concrete jungle, as exemplified by that one story from the Bronx.

Benji Jones: Then I will say like, that raises an important point, which is that, unlike these big habitats, often small chunks of land are not considered super valuable even by the conservation community, historically, at least. The US doesn't have a lot of legislation to protect these small spaces, even though they do have really important value. This actually is a problem all over the world. Small spaces just don't get the same. They're not treated the same as big spaces, even though I think that some researchers would definitely argue that they should be.

Brian Lehrer: From the Bronx, we'll go down to Brooklyn for Molly and Kensington, you're on WNYC. Hi, Molly.

Molly: Hi. My patch of grass is technically very big. It's the Ocean Parkway Greenway. It goes from Church Avenue all the way to Coney Island, but it's very narrow. I just moved to this neighborhood. I'm a native New Yorker, just bought my first apartment. There's something so calming about this patch of grass right outside my house with these benches, even though it's like eight lanes of traffic. The trees and the grass make it somehow very relaxing.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much. That story too could be resonating with a lot of people whose heads might be nodding. We've seen the New York City Parks Department has a number of these little micro plots where you'll see the parks department and signee there because they run them but yes, they might be adjacent to a highway.

Benji Jones: Yes. It's important to talk like you mentioned just the calming effect of some of these spaces, especially amid like a very busy city. I have this experience all the time. There's actually a lot of research that shows that having green spaces creates mental health benefits for people. There's more than one way that these spaces benefit us.

Brian Lehrer: All right. We've touched the Bronx, we've touched Brooklyn. Here's Harry in Queens in Forest Hills. You're on WNYC. Hi, Harry.

Harry: Hey, how are you? My parklet Flushing Meadow over the years, there have been more tennis stadiums installed. Recently, a corner of the park reopened and it reopened to additional sidewalks, which takes drain away and also additional roadways. You do have people walking on the roadways and cars zipping by, I feel the perimeter roadway should be shut down because at rush hour, people use it as a shortcut.

Regarding the wildlife, there's muskrats, which are interesting. They look like mini beavers, but they have a straight tail instead of a flat tail. There are raccoons, rabbits and also you get different types of waterfowl. A few years ago, there was some cattle egrets, they're no longer around. You get standard cranes, which are also called American cranes. Those are the white cranes. Occasionally, you get a heron or a sandhill crane, which makes them about a few 1000 miles.

Of course, sometimes you have Canada geese, who just winter there, they won't fly further south. Regarding, birds and other wildlife, that's fine. Oh, final note around the highway overpasses that the city has asphalted over just for the two to four-week use of the tennis stadium, car should not be allowed at all. Anyone who has a tennis ticket, take mass transit, take Amtrak something to get here. No cars.

Brian Lehrer: Harry, thank you very much. Well, there's a guy from Queens who knows the difference between a muskrat and a beaver. Thanks.

Benji Jones: Exactly. I think it's like amazing that there are muskrats in New York City.

Brian Lehrer: Let's see, we may run the five boroughs [unintelligible 00:16:36]. Daisy on Staten Island on WNYC. Hi, Daisy.

Daisy: Hi. I could not be more thrilled that you are talking about this subject because I have a very clear and distinct favorite patch of grass. It's the serpentine grasslands of an island. It's actually globally imperiled and it is the only habitat that they have in all New York City is in Staten Island. Biologically unique based on its geology, which is pentane night. It has really unique soil chemistry and that it has very low nutrients, high and heavy metals.

It's actually not very hospitable to most plants in our regional flora so we have a really biologically unique flora that grows in the serpentine grasslands and they have diminished in size over time as a result of natural succession but they are a refuge to a suite of state endangered plant species [inaudible 00:17:46] by its beauty. It's unfortunate that these really incredible areas have just diminished over time. Tiny fragments of serpentine habitat that still persist within Staten Island and I just think it's a huge priority-

Brian Lehrer: Daisy thank you.

Daisy: -to be able to protect and manage them.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much. We've heard from Brooklyn, the Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island. I'll complete the five-factor and be the Manhattan representative and say, up here in northern Manhattan where I live for Tryon Park and Inwood Hill Park. Oh, my god, you can literally take a walk in the woods and still be in Manhattan. Boy, [unintelligible 00:18:32] improve the quality of life. We'll tag this with one more from the Bronx because it looks like Ruth from the Bronx is putting together a grant to save small patches of grass, in particular right now. Ruth, you want to tell us the story. Hi there.

Ruth: Yes. Hi, Brian. Longtime listener, first-time caller. I'm so excited like the last caller. This is very close to my heart as well. There's a little patch of grass along the hutch River Greenway in the Bronx, for those in the Bronx is right behind Waters Place in medical pavilion. There's a really nice patch of milkweed plants and that's the only plant that supports monarch butterflies. My collaborator, Patti Cooper, who is a retired employee from Bronx Zoo Wildlife Conservation Society.

She was watching the eggs being laid and other little creatures living on these milkweed plants. Then it got mowed down before any monarch butterfly could hatch. We're working together now and I just submitted a grant application to Bronx Council Arts last night to try and run an art education conservation program in the Morris Park section of the Bronx at Morris Park Library to actually do what your guest is saying and try to show people Ghat you can do small things and grow pollinate plants in your garden and we really want to try and get a group of people together to work to try and save these small patches of areas that are now supporting the endangered monarch butterfly in meaningful ways and just trying to help support the environment with these precious small areas.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you so much. Benji Jones?

Benji Jones: Just want to underscore the value of milkweed shout out to native milkweed. It's a super important type of plant to put in your garden to support monarchs and other species. I believe the New York Parks Department also has a list of native plants that you can plant so check that out if you're interested in ripping up your lawn and planting native species.

Brian Lehrer: Let's wrap this up by going from the small back to the big, and listeners, if you've joined us in the middle we're talking to Benji Jones, Senior Environmental Reporter at Vox whose two most recent articles are quite a contrast. One called The Surprising Value of a Small Patch of Grass to Save More Nature, Think Small. His other is about Lula's election victory in Brazil and the implications for the Amazon so going back to the Amazon for a last thought. Does the United States play a role politically in what Lula does to save the rainforest that has global implications?

Benji Jones: Yes. There was a lots of talk in the last year about providing funding from the US to Brazil to help it meet a net zero deforestation target by 2030. I don't believe there's been a lot of money dispersed yet from those conversations. Definitely, the international community does play a role in supporting funding of conservation in the Amazon.

Especially when climate change, which is largely the wealthier countries are responsible for climate change, which also harms the Amazon and so a lot of folks think that wealthier countries like the US should take responsibility for their outsized role in rising greenhouse gas emission so certainly, there is a role that the US will play in Amazon conservation and Biden has talked a fair amount about this.

Brian Lehrer: Benji, this was great. Thanks so much.

Benji Jones: Thanks so much, Brian. My pleasure.

Brian Lehrer: Benji Jones, Senior Environmental reporter at Vox.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.