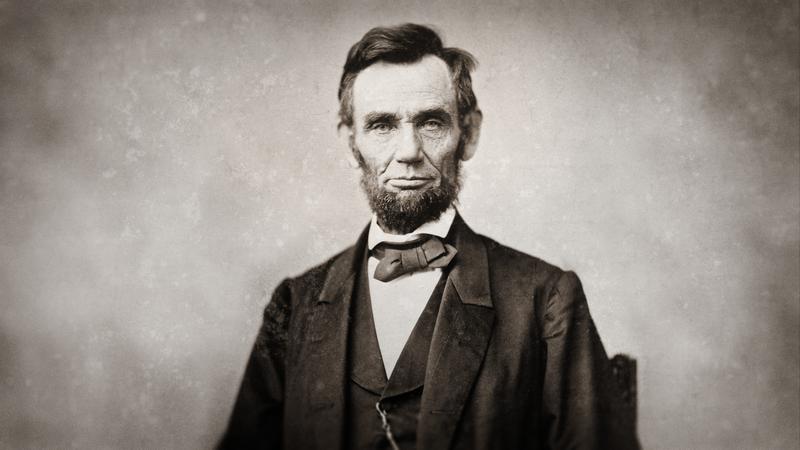

Lincoln and Emancipation

( Courtesy of Apple TV+ )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone, on President's Day when we jointly observe the February birthdays of America's first President George Washington, and our 16th Abraham Lincoln, to whom it was left to resolve the fissure between slavery, and the promise of freedom in the Declaration of Independence, because President Lincoln freed the slaves.

A new docuseries on Apple + examines that oversimplification, not to fully debunk it, or rewrite the history, but to let in some nuance and complexity, adding up to a new depth of honesty. Here's a clip from the series. Bryan Stevenson best known for his book, Just Mercy and for spearheading the national memorial for peace and justice, memorializing by name, thousands of forgotten African Americans who were lynched in the first 90 years after slavery. Bryan Stevenson on so much buried history and the protest movement of today.

Brian Lehrer: What we're seeing today is really dramatic evidence of what happens when you fail to talk honestly about your history. We have to tell the truth about who we are and about how we get here.

[applause]

Speaker 1: That is why we're carrying this statue down.

[applause]

Brian Lehrer: Bryan Stevenson from the series Lincoln's Dilemma, it premiered on Apple + on Friday, and it used as its basic thesis the book Abe: Abraham Lincoln in His Times by historian David S. Reynolds includes the actual words of Lincoln and Frederick Douglass as spoken by the actors who play them. We will hear one of each. It features the commentary and insights from a very long list of historian and thinkers, including our guest now historian, Kellie Carter Jackson, Professor of Africana Studies at Wellesley College, and author of the book, Force and Freedom: Black Abolitionists in the Politics of Violence. Professor Carter Jackson, thanks so much for giving us some time today. Welcome to WNYC.

Professor Carter Jackson: Hi, thank you. Thank you for the time.

Brian Lehrer: At its core, what was Lincoln's dilemma in a nutshell, to preserve the Union and uphold the Constitution, pre-13th amendment, or free the slaves?

Professor Carter Jackson: All of the above, [laughs] all of the above. I think Lincoln's dilemma is definitely trying to restore the Confederacy back to the Union, and it becomes a war of abolition. It becomes a war to abolish the institution of slavery. I also ultimately argue that his dilemma is really not what do we do with Black people, but what do we do with white people? How do we handle white supremacy? He doesn't live to see the end of reconstruction, but all of the fallout and the backlash that comes with reconstruction is a big part of his dilemma.

Brian Lehrer: You're first quoted in the series, saying that Lincoln entered office wanting to be the great unifier, not the great emancipator. I think this clip that we're about to play illustrates that. Now, no one has audio recordings of Abraham Lincoln, of course, but the actor, Bill Camp reads his words throughout the series, as in these 20 seconds.

[music]

Bill Camp: My Paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it. If I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it. If I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that.

Brian Lehrer: Wow, "If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it". That quote taken by itself is so amoral, maybe is the word. When was that and what was the context?

Professor Carter Jackson: Sure. That was Lincoln's first inaugural address. When he is being sworn into office, the speech he's giving is really saying, "Hey, listen south, I'm not trying to harm you. I want to preserve the institution of slavery. I want to protect and enforce the fugitive slave laws so that when fugitive slaves ran away, that they could be captured and returned and sent back to their slaveholders."

He's trying to throw the south as many carrots as he possibly can to keep them from seceding from the union. That speech was one of the ways he was trying to persuade them that he was not the abolitionist president. That he was anti-slavery, but he was not an abolitionist. There's a distinct difference between those two ideas. It's important to also sort of tease out those differences.

Brian Lehrer: I think those words as recited by Bill camp, Lincoln's words, were not spoken in a speech, were rather from a letter to Horace Greeley, is that correct?

Professor Carter Jackson: Oh, yes, yes. The letter to Horace Greeley talking about his intentions for what he just wanted to do to appease southern interests.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, but was Lincoln's relationship to enslavement as simple and detached as that clip sounds?

Professor Carter Jackson: No, I think what's so great about this documentary is that everything is so complex and layered, and nuanced, and that Lincoln comes to a lot of decisions and then changes his mind once he gets more information, and that over time, we see how Lincoln evolves in his thinking and his ideology, how he becomes persuaded by other Black leaders, by other white radical republicans who are able to get him to think about the ways that slavery is so harmful to this country and to also think about the ways that Black humanity has to be validated at this moment.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, has anyone out there right now been watching Lincoln's Dilemma yet? Any questions or comments about it or a specific question about Lincoln's role in ending slavery? 212-433, WNYC, on this President's Day, 212-433-9692, or in general, as you've learned deeper versions of American history since grade school, has that added to or subtracted from your appreciation of those who came before Lincoln included?

212-433, WNYC, 212-433-9692, or tweet @BrianLehrer with historian Kellie Carter Jackson. On Lincoln's place on the political spectrum at the time, the series describes how, on the one hand, the confederacy did think he was out to end slavery, but on the other, abolitionists did not see him as on their side. Who then was his core constituency as he ran for president in 1860?

Professor Carter Jackson: White people, I think [laughs] that's the easiest way.

Brian Lehrer: [unintelligible 00:07:14] couldn't vote.

Professor Carter Jackson: The easiest way to say it, I mean. Yes, yes. [chuckles] Black people are not-- The 15th Amendment is nowhere near insight at this moment. In some cases, there are small numbers of Black people who are able to vote in northern states, if they were property owners or had a certain amount of wealth, but for the most part, Black people are not voting wholesale.

Lincoln's primary constituency is white northerners. Some white southerners too are sympathetic to his ideas, but for the most part, he's trying to, again, appease those who are anti-slavery, who don't really want the institution of slavery anywhere near northern boundaries, but at the same time are not necessarily abolitionists, they don't believe in the immediate institution or abolition of slavery.

They certainly don't believe in Black humanity wholesale. Lincoln has to be persuaded to change his mind, and he does, but initially, Black people were not at all his core constituency. It's interesting because southerners, in particular, used Lincoln as a way to say, "Oh, he's the president for all Black people. Oh, if you want someone that's going to put Black people first, it's Lincoln." They used that in a pejorative way to scare people into believing that if Lincoln were elected, that the first thing he would do is free the slaves.

Brian Lehrer: He took off his after secession, didn't he?

Professor Carter Jackson: Yes, he did. Well, all throughout his, by the end of his inauguration, I believe about seven states have seceded from the south, it becomes a domino effect, in which, state after state starts to leave the union. First starting with South Carolina. Lincoln, in his first few days of the presidency, is scrambling, because, they are essentially on the brink of war, if not at war, the moment he began his presidency.

Brian Lehrer: The film establishes a difference at the time that I didn't know about, between being an abolitionist, and being anti-slavery. Can you talk about why that's an important distinction, and how being an abolitionist and being anti-slavery at that time were different at all?

Professor Carter Jackson: Yes, I think that's an idea, especially among the general public that everyone in the north was an abolitionist. That's just not true. The abolitionists only made up about 1% of the nation's population. They were small, some might call fringe or fanatical group of people that wanted the immediate abolition of slavery, the immediate end of slavery. If you're a Black abolitionist, you didn't just want emancipation, you also wanted wholesale equality. You saw them as part of the same agenda. You can't get equality without emancipation. You can't get emancipation without equality, but if you were anti-slavery, it didn't necessarily mean that you believed in those things, you may dislike slavery because it undercut your economic bottom line so no one's going to pay you $10 an hour to do a job and they can get a slave to do it for free. If you are a white person living in Ohio, you don't want slavery because that threatens your ability to make a wage.

A lot of white northerners were against the institution of slavery, but they still didn't like Black people and they still didn't want Black people around them and some of them were even pro-slavery because if you lived in, let's say Lowell, Massachusetts, you worked in those textile factories that manufactured that cotton, that produced that cotton and a lot of your livelihood was dependent upon the production of cotton that slavery produced so it's a mixed bag.

Brian Lehrer: That's such an interesting piece that I think gets lost to history. You could be a low-wage worker, small farmer who opposed slavery from self-interest not from memorial standpoint, but because you didn't want to have to compete with unpaid labor, right?

Professor Carter Jackson: Absolutely, yes.

Brian Lehrer: We're getting a call on this point or something related from Nicole in the Bay area of California. Nicole, you're on WNYC with historian Kellie Carter Jackson, one of the sources in the new Apple TV docuseries Lincoln's dilemma. Hi Nicole.

Nicole: Hi. Hi, Brian. Hi, professor. I'm just so happy for hearing this discussion. I'm an eighth-grade social studies teacher and I've been teaching this narrative for over a decade and I'm just so happy to feel it affirmed and I just called saying what you just said about how hard it is to teach my students that someone could be against slavery and could care less about the human of African Americans. That, I feel like is one of my biggest challenges that not everyone who was anti-slavery was an abolitionist and that's really hard for them to get and the role of the frontier in the west. Thank you for articulating my point and Brian, thank you so much. I listened to you at seven o'clock in the morning. [laugh]

Brian Lehrer: California time.

Nicole: Yes, it's one of my joys [inaudible 00:12:30] but anyway, thank you, professor.

Brian Lehrer: I'm honored, Nicole.

Nicole: Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much to have your ears at early in the morning. Anything else you want to add to that aspect of the story professor?

?Professor Carter Jackson: That's a such a good point. One of the ways that if this will help her in her classroom is I try to give my students the numbers because I think that letting them know just how economically profitable the institution of slavery was explains why people held onto it so tightly. If you think about the fact that Mississippi becomes one of the richest states in the union, if you think about the fact that most, if not almost, all the millionaires that are a part of this country reside in the US south and have a role in the institution of slavery.

Slavery was so intensely profitable, nothing trumped the institution of slavery profit-wise, other than like the real estate of what is the United States of America itself. When people realize, "Oh, this is big business, this is king cotton," I think it allows people to understand why even more realistically people were not willing to relinquish the institution because it fortified their lives economically.

Brian Lehrer: Again, Nicole, thank you for calling from the Bay Area, 212-433-WNYC-212-433-9692. A big part of what the docuseries aims to do and it's even related to this idea of being anti-slavery without necessarily being an abolitionist from a moral standpoint, it's to show that Lincoln got to the place of ending slavery, not by looking inside or not only by looking inside and soul searching, but by being led there, pushed there, awakened even by grassroots movement and especially by Frederick Douglass, who was an abolitionist and, of course, the great order and statesman who would escape from enslavement himself. Can you talk about Douglas's influence on Lincoln?

Professor Carter Jackson: Oh man. Absolutely. Douglas is, I tell my students all the time, he's my historical boyfriend. I love Frederick Douglass so much and that's because he's so responsible for much of Abraham Lincoln's success. It is Frederick Douglass that is first and born enslaved, escape slavery, writes his own narrative which becomes the bestselling book. He goes on to become an abolitionist, give all of these speeches across the country and he's constantly holding America's speech to the fire, but really Lincoln's feet when the war breaks out.

He does a number of things he says to Lincoln one, you need to make this a war of abolition. If you want to win this fight, you have to promise to free the slaves you have to create what becomes the emancipation proclamation. Then he also says, "You have to let Black men fight. No one has got more of a dog in this fight than enslaved people than Black people. If you equip them to fight they will turn the tide of the war," and they absolutely do.

Then when Black shoulders fight in the war, he's like, "Wait a second, Lincoln, you have to pay them equally. You have to pay them fairly." They were paying Black people different wages than white people. It's mind-boggling when you think that all of these soldiers are giving their lives they should be paid the same. Lincoln, does all of the things that Douglas asks of him, but it's a real confrontation about getting Lincoln to be persuaded to make these decisions and see the rightness in it and then also the military necessity in it as well.

Brian Lehrer: By ending slavery how do I put this? If I'm understanding you correctly and this would be a historical insight that I definitely didn't learn in middle school. It wasn't just fighting the war to end slavery, it was ending slavery came to be seen as necessary to winning the war. Is that what you're saying?

Professor Carter Jackson: Absolutely. This war is not one, unless abolition is at the center of it, unless abolition is on the table, on the agenda. One of the ways it becomes an issue on the table that Lincoln has to reckon with is because enslaved people are leaving by the trolls. They're leaving by the hundreds of thousands and he can't send these people back to the plantation.

The people who own those plantations most of them are already off to warfighting and so when Lincoln sees that slaves are leaving and they're not coming back he has no other choice, but to make it a military necessity to cripple the back of the south and to say, okay, if this is the one thing that's holding you up and make no mistake slavery was then that's the one that we are going to cut off.

He issues the emancipation population. It frees about three of the 4 million people enslaved other states that were border states or states that were not necessarily in rebellion states like Delaware or Maryland had already started to free their slaves as well. I tell a lot of my students that when we get to the 13th amendment, we can credit Lincoln for freeing the slaves but really, the 13th amendment is the coroner support. It's the official time of death, but slavery died on the ground because enslaved people themselves killed it.

Brian Lehrer: As an example of Frederick Douglass's guidance to Lincoln, here are some Frederick Douglass's words, voiced in the docuseries by Leslie Odom Jr. This is against the idea of colonization and I guess actually before we play this, you should set this up because didn't Lincoln, at one point, advocate for colonization for the formally enslaved outside the United United States.

Professor Carter Jackson: Yes. He did before as he's drafting the emancipation population, one of the things he says is, "If we figure out these Black people, what are they going to do? Maybe we should send them away. Maybe we should send them back to Africa. Maybe we should send them in Haiti," he thinks that deportation or colonization might be a solution for Black people that he can't imagine a world in which Black people are free and living in America like he can't wrap his mind around that.

Douglass is like, "No, we were born here, we are American, we built this country deportation has to be off the table. There's also another aspect of that as well in which he wanted to compensate slaveholders for their property and that failed as well.

Brian Lehrer: Here's a little of Frederick Douglass on that idea of colonization.

Frederick Douglass: There is no sentiment more universally entertained, no more firmly held by the free colored people of the United States, then that this is their native land and that here, their destiny is to be wrought out.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Monique in Terrytown, you're on WNYC with historian, Kellie Carter Jackson. Hi, there.

Monique: Hi. Thank you very much for this wonderful series here.

Professor Carter Jackson: One of the things that really struck me was the economic calculus in all of these decisions and it really resonated with our current situation about legal immigration and undocumented people because they're virtually, I see them as almost invented servants where they're living in the shadows and they're very much exploited on so many construction sites and cleaning ladies and everything else. Having just going to an honest conversation about the dignity of these people and how giving dignity to the process of this country. I just wanted to bring up the point that we are still going to dealing with these issues about equal rights in our country so thank you.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you for making that connection. Anything you want to say about that professor?

Professor Carter Jackson: No. I just want to echo because that's an amazing point. What I love about this documentary is that there's so much resonance with today, so much relevancy, so we can look at things that happened over 150 years ago and say, "Wow, what has changed? What still needs to change? What still needs fixing?" I think this documentary really points a light on that as well.

Brian Lehrer: John and Franklin, New Jersey. You're on WNYC. Hi, John.

John: Hi, good morning. I'm hearing this and I'm hearing many similar conversations and many historical conversations like this. I'm wondering, are we feeding into the anti-critical race theory teaching? I mean are there people out there who are going to take documentaries like this and say, "See, see, we're heading toward critical race theory?"

Brian Lehrer: John [unintelligible 00:21:44]--

John: [unintelligible 00:21:45], my personal opinion.

Professor Carter Jackson: I--

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead, go ahead, John finish. You can express your personal opinion.

John: My personal opinion about critical race theory is that it should be embraced and it should be explored and it should be taught but you're going to get this fringe out there who are going to take documentaries like this, at least I feel like they're going to take documentaries like this and run with it and pump it up into be into this critical race theory effort.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much. Yes, you think people are going to watch a documentary doc series like this and think, "Gosh, they're even tearing down the good guys. They're tearing down Abraham Lincoln?"

Professor Carter Jackson: I think we have grossly underestimated how important history is. I think a lot of times in my class, students don't like history because they think it's just dates and names and places. The more we live in this world, the more we realize that history has major consequences and major, all of the causes, all of the things that allow us to understand our own citizenship are a part of history, the discipline of history and so, when I worry about the pushback it's not so much for me about critical race theory because I think we've made this big bucket and then dumped anything that has to do with race in it, critical race theory is something that's very specific and really only predominantly taught in law schools but we've thrown in like diversity, equity inclusion in the CRT bucket and anything that we think is racialized in that bucket.

That is a little problematic. We have to be able to have honest conversations as Brian Stevenson said at the start about what we have done as a country who we are as a country. You don't understand that unless you understand the civil war, unless you understand this moment. While I'm a little concerned that it might be vilified, I also understand that anything and everything has become vilified that has to do with even topics that we think are benign.

If you want to make a controversy out of something, I'm sure that you can but for those who really want to learn and get context and get nuance and really complicate this history, I think this documentary is perfect for them.

Brian Lehrer: The documentary includes footage of protest against and removal of a Lincoln statue in Boston. To put that in context, let me ask you a question about that. I believe as NPR reported at the time around the end of 2020, workers dismantled the statue of Lincoln in Boston after the city agreed with protestors who said the Memorial is demeaning and lacks proper context. The statue depicted Lincoln holding his hand over a kneeling Black man.

A figure modeled on Archer Alexander, the last man captured under the fugitive slave act so when the opponents of teaching nuance history say they're even tearing down Abraham Lincoln I think, tell me you on that incident, again, it is depicted in the film. It's not to say anything about Lincoln really, it's just to show, to depict a statue in which Black people are represented as so subservient.

Professor Carter Jackson: [sighs] The replica, the original, I should say statue is in Washington DC. That statue is complicated. I hate though it's complicated on everything but it's complicated because a lot of these statues were funded by and purchased by Black people. At the time, this was something that would've been considered progressive for lack of a better word but in our 2022 eyes, it's offensive. The way that we can understand a moment like this is instead of tearing it down or demolishing it, having something that gets added to it, a plaque that says, "While this image of a subservient Black person is what we see here, you should know that enslaved people freed themselves and here's how they did it".

Ways that give much more perspective to what is taking place in this image and why these images were chosen. I mean, this is why art history is so important because you can't just look at a picture without having an explanation, without having context, and that matters. It really colors how we understand things but sometimes, I do agree with the notion that if we can't explain it or explain it well, then maybe we can take a pause and take it down until we can find something that will work, and that will encapsulate it.

Brian Lehrer: One more call, Roland in Albany, you're on WNYC. Hi, Roland.

Roland: Good morning. Thank you very much. This is a fantastic approach. Without getting into the issue of critical race theory, why do you think America has not dealt front and center with the economic impact of slavery? I met Nelson Mandela when he shortly after he was released from prison and he talked about a truth and reconciliation commission being needed and a process because otherwise, you thought South Africa could never move forward.

The reality of America is that slavery wasn't just people like me being held on plantations in the south. It involved, man, kids that I've seen in Manchester England that were made wealthy from cotton money. It involved the English empire outlawing British outgoing people in the British [unintelligible 00:27:42] in India from wearing [unintelligible 00:27:44] requiring them to wear cotton cloth, cotton that was farmed in Alabama and South Carolina made millions of dollars for people in New England because they owned the companies that made it and made billions of dollars off people in England who sold it all over the empire.

Unless we can embrace the economic impact, we're never going to move forward. One more point, the moment that Robert E. Lee walked out of the courthouse at [unintelligible 00:28:12] the value of the people that were enslaved, that walked the entire collective value of every other asset in the United States. In other words, Black slaves who were freed were more valuable than all the machinery, all the cash on hand, all the cash not on deposit, all the commodities, all the other estate, bonds, stocks, musicals, instruments, art antiques, and everything else in the country-

Brian Lehrer: Which--

Roland: -and that's why slavery was so important.

Brian Lehrer: To the owners correct but [unintelligible 00:28:53]--

Roland: Not just to the owners.

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead.

Roland: The economy's connected. I mean, I went to an historically Black college that existed after slavery. I went to an Ivy League College that got rich because of slavery and that's kind of a relationship that unless we accept that, we're going to have a hard time ever moving forward.

Brian Lehrer: To you, Roland, what would a truth and reconciliation commission South Africa style have to do in this country?

Roland: An acknowledgment because my grandmother, I am the great, great-grandson of the 15-year-old slave in South Carolina who was impregnated by her 55-year-old owner. I wouldn't be here without slavery and unless we accept that. When I tell people that, I've written books, I've written articles. People say, "Well, why do you want to avoid that"? Well, it's not that I want to dwell on that, it's that that's what happened. If I can't get white people to understand that, I'm always going to be somebody whose kids get stopped because they're Black, who gets hassled because he's Black because well, we can't move past it unless we acknowledge what that past was.

Brain Lehrer: Roland, thank you so much. Thank you. I'm going to leave it there because we're running out of time, but thank you so much for your call we really appreciate it. That's a pretty good way to end professor-

Professor Carter Jackson: Yes.

Brian Lehrer: -but anything that you would want to say in response to Roland's call?

Professor Carter Jackson: He's absolutely right and it's sobering and we have to have honest conversations in this country, not just about slavery, but also about race and racism and how it has played out and had detrimental devastating effects in this country. Until we can do that, we're still going to be at a stalemate and it's just unfortunate and it's also why I think documentaries and books and conversations like this one are so critical to moving us to where we need to be.

Brain Lehrer: By the way, you co-host the podcast, This Day In Esoteric Political History which I will say-

Professor Carter Jackson: I do.

Brian Lehrer: -you do with a former producer of this show, Jody Avirgan who contributed a lot to the Brian Lehrer Show as a producer for a number of years. I see it comes out on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Sundays. Want to give our listeners a preview of something upcoming or talk about a recent episode?

Professor Carter Jackson: Yes, yes. We just finished an incredible week on Black History Month where we featured for a week, all of our shows on Black History Month, and that was a lot of fun. We have another show that's upcoming about the history of [unintelligible 00:31:44] and so it's just so much fun to be on that show. I have amazing co-host, Jody is awesome. Nikki is awesome and so if you're looking for a new podcast that's short and sweet and then we'll give you something esoteric about political history, we are your people.

Brain Lehrer: Kellie Carter Jackson, professor of Africana Studies at Wellesley, author of Force and Freedom: Black Abolitionists and The Politics of Violence and co-host of This Day in Esoteric Political History, all four episodes of the docuseries; Lincoln's Dilemma that she is quoted in and why we invited her on the show today are now streaming on Apple +. Thank you so much. Great conversation. I really appreciate it.

Professor Carter Jackson: Thank you.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.