Iconic at 50: Black Sabbath's 'Master of Reality'

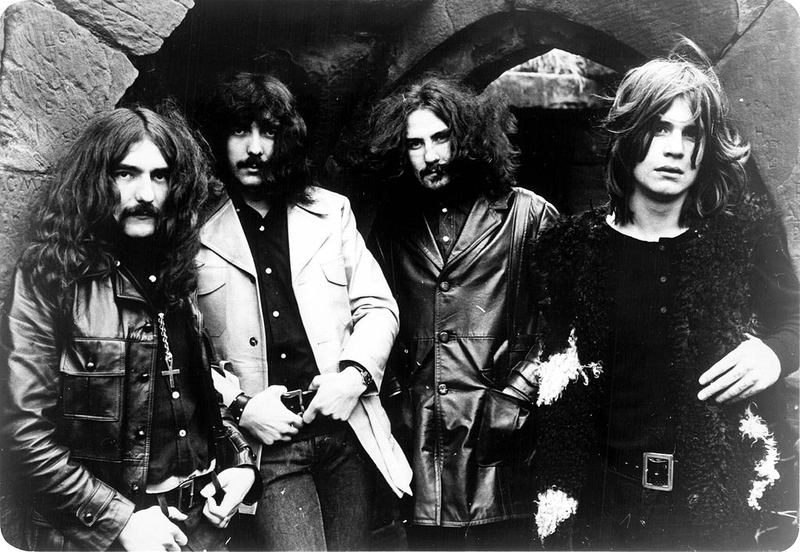

( "Sabs" by Warner Bros. Records - Billboard, page 7, 18 July 1970. / Wikimedia Commons )

[Black Sabbath's Into the Void playing]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC and that is Black Sabbath's Into the Void from their 1971 album, Master of Reality. This summer we're looking at, or rather listening to, some iconic albums that turned 50 this year and digging into the political and social context in which they were made and their impact on both music and culture.

1971 is seen as a pivotal year in various genres of popular music.

We've already discussed Marvin Gaye's album What's Going On, and Joni Mitchell's album Blue in this series. Today's album is Master of Reality by the band Black Sabbath. Our special guest for this is Henry Rollins, you may know him as the former frontman of the hardcore punk group, Black Flag. Henry hosts a weekly radio show on NPR member station KCRW in Southern California. Maybe you know him from that. He's also a self-described Black Sabbath advocate. Thanks for doing this, Henry. Welcome to WNYC.

Henry Rollins: Oh, thanks, Brian.

Brian: Before we get into some songs from the album and play some more music clips, for our listeners who actually may not be familiar with Black Sabbath, that's vocalist Ozzy Osbourne, guitarist Tony Iommi, bassist Geezer Butler, and drummer Bill Ward. For the uninitiated, even if they've heard of Ozzy Osbourne, can you talk a bit about who they were before Master of Reality came out?

Henry: Well, Master of Reality was their third album. It came out in July of 1971. It was preceded by the Paranoid album, which came out in September of 1970, which gave them a huge hit the song Paranoid, which made them huge all over the world, especially in America. Before that, in 1969, they put up the album Black Sabbath, which had the song Black Sabbath.

These three albums really established them and kind of established a new genre, what eventually became known as heavy metal. I think by the time Master of Reality came out, you have to remember that between the first and third albums is a little under a year and a half. So the band is probably being poked by the record company, like, "Keep making music because it's selling," and that often is the ruin of a band.

But Black Sabbath was so good, they made three really strong albums. I think the most together of those three albums would be the third one, Master of Reality, as far as sounds, playing, chops, the way the rhythm section swings, how about the quality of the vocals and Ozzy's singing, the songwriting, the compositions. The song Into the Void that you just played I think is one of Black Sabbath's masterstrokes. It's my personal favorite Black Sabbath album and has been for about 40 years or so.

Brian: Let's talk about the genre that you just called heavy metal. In a recent interview for Loudwire, the bassist from Black Sabbath, Geezer Butler, put it this way in terms of a social context for the emergence of that. He said, "We grown up in the aftermath of World War II. Aston, where we were from, still had bombed out buildings and neighbors with war wounds. At the time of Master of Reality, Vietnam was raging, the Cold War was at its coldest, the troubles in Northern Ireland were close to home, a few others were singing about the underside of life, but we had the heaviness to hammer the subjects home."

So you want to talk a bit about how the heaviness of the instruments and the lyrics like we heard in the intro to the song Into the Void help convey the experience of the band's generation at that time?

Henry: Sure. You have to remember parts of England at that time, young people were growing up not seeing trees. Going years and years of their life never eating real eggs, you were still on powdered eggs. As Geezer said, parts of your town are bombed out. After school, you're playing in the ruins of what World War II wrought upon your town.

The band is from the Birmingham area, which is central England. Very, very industrial. I've read an interview with Tony Iommi at one point where he said, "We were just emulating the sounds of our city. We love the clanging and banging of the guts of a factory." I think that the Black Sabbath guys were just not inhibited by the cruel people in London. They're kind of remote in the center of England, left to their own devices.

I think they just wrote lyrics about what they were seeing around them, and what they were feeling. They weren't trying to necessarily make it on the radio. I think that ended up being one of their strengths. They weren't trying to please, necessarily. They were just doing what they thought was the right thing to do without concern for radio success.

I've talked a lot with all four members of Black Sabbath, and they make jokes about how they're failures. I'm like, "How can you say you're a failure with 75 million records sold?" Probably more by now. They just laughed and go like, "No one likes us." I'm like, "Come on. Everyone likes you, guys." So I think they were just kind of telling you what was on their minds. In those days, it's kind of a standout thing to do. In fact, I would go as far as to say it's pretty punk rock.

Brian: In fact, I wonder if we have any Sabbath fans or general metalheads out there. We can take just one or two phone calls in this segment as we continue to talk to Henry Rollins and play some tracks. Listeners, what did Black Sabbath's Master of Reality mean to you at the time, if you were into it at the time in 1971? Do you have a story of when you first heard the song from the album or anything like that? If you're younger, how were you introduced to the album, and what has it meant to you in your personal life, or political or social context of more recent times in 1971? 646-435-7280. 6464-435-7280, or tweet your thought @BrianLehrer.

In this series, Henry, we've talked a lot about how the Vietnam War figures into the iconic albums of that year, but we haven't really gotten into what we could consider the even broader context, which was the Cold War. That bird's eye view is something that really comes up in this record again, and again, in the lyrics. Here's a bit of the song, Children of the Grave.

[Black Sabbath's Children of the Grave playing]

Brian: Those lyrics were a little hard to hear.

"Must the world live in the shadow of atomic fear?

Can they win the fight for peace or will they disappear?"

Now, the UK was not essentially a part of the Vietnam War as we think of the US, but you want to talk about how the themes of mutually assured destruction as they refer to there in that line about atomic fear come up in this album?

Henry: If you think about the Vietnam War, as horrible as it was, it was very localized to Vietnam, parts of Cambodia, and Laos. If you're in England, you're not getting any on you, if you will. But nuclear destruction, if there's wind, you're going to suffer, so that brings in all of humankind. I think that's a bit what they were getting at with Children of the Grave. There's a line in there towards the end of the song, "All you children of today are children of the grave."

I think Geezer Butler wrote the lyric. He is the primary songwriter, lyric writer for Black Sabbath, and a really great lyricist, too. I think he was trying to say, "We're all in this together," because of the nature of what a nuclear bomb can do. The Cold War, as far as your danger level, it could be everybody's war. You remember from 1962 October, the Cuban Missile Crisis we find out later, decades later, Secretary of Defense McNamara met with his Russian counterpart as two old wise men. We find out that the Russians were much closer to pressing the button like we were. It was much worse than our worst nightmares. It was apparently very, very close to go, which we might not be having this conversation right now.

I remember being a young person listening to Master of Reality. It was the idea of nuclear destruction and environmental damage that struck me as being really amazing about Black Sabbath, like what they're getting at lyrically. They got every bad review known like, "They're dumb. They're thugs. They can't play." If you listen carefully to the records, the rhythm section swings, the guitar player is amazing, Ozzy is an iconic singer, and the lyrics are anything but stupid.

Brian: We have some interesting looking calls coming in. Let's take a couple. Catherine in Manhattan, who remembers being 14 in 1971. Hi, Catherine, what's your Black Sabbath story?

Catherine: Hi there. I grew up in Holland, Michigan, which is a very conservative area, but for some reason at that time, in the 1970s there were many people who were very knowledgeable about music and art, et cetera. My best friend and I were taken to a concert in Grand Rapids, Michigan by my friend's older brother. There was such an outpouring of young people. Everybody was so excited to attend this concert because in my area there weren't a lot of bands that came through. Frank Zappa came, that was fabulous.

But then, Black Sabbath was another experience. In the vestibule, as we were getting into this space, it was just packed with young people. It was so packed it was one of those experiences where people were getting lifted off the ground, everyone was trying to push in, there was condensation on the windows, and people were writing, "I can't breathe." It was very impactful, this whole experience. Finally, everybody got in and the band was so unbelievable. It was a small space and there's so much sound. I think that it was a coming of age for many of us who lived in that area.

Brian: Catherine thank you so much for that story. We're going to go right to Taylor in Elmhurst. You're on WNYC. Hi, Taylor.

Taylor: Hi, good morning. Thank you for having me. I grew up in El Salvador in the 1970s. My brother introduced me to Black Sabbath. That was in the middle of the war that we were having and that was our sanctuary. That was the music that-- we were the outcasts. When we were young and poor you were either in the military or you were either in the guerillas. There was nothing in-between but there was in-between. It was us, the outcast. The poor people that had nothing left to live for. Black Sabbath and all those lyrics-- "Children of the Grave" was so personal. It's so normal at the time to see dead bodies on the sidewalk and you would wonder, "Is it really that true?" That music, personally to me, it was a sanctuary. It was this fascinating-

Brian: This is an amazing story and don't go away yet Taylor. Henry Rollins, is this a surprise to you that people were listening to Black Sabbath in El Salvador in 1971?

Henry: That doesn't surprise me at all. I think Black Sabbath is one of those rare bands that anywhere there's electricity, there's going to be fans because they speak to real people. That doesn't surprise me at all.

Brian: Go ahead, Taylor. You go.

Taylor: If I may add the following. We were that poor. Visualize one of those parties of, let's say, the Bee Gees, one of those pop musics. You would have the preppy boys going in, dancing with the girls and where were the outcasts? They couldn't even have money to go in and buy a soda pop. We were the ones outside just wondering, "Can we ever go in?" But that music sucked. Then when it came to Black Sabbath that was us.

Even grandma used to tell me that we were listening to devil worshipping. It had nothing to do with it. It had to do with us. It was something that connected us, that we understood. In my days at the time, I think if you were listening to bands like Sabbath, Deep Purple and Led Zep, you were thought to be like a pothead which didn't make sense. We were just enjoying it. There was no [sound cut] [crosstalk]

Brian: Taylor, thank you so much for your call. Thank you, thank you, thank you. I'm going to play another track excerpt coming out of one thing that he mentioned because Black Sabbath has been associated with Satanism since the beginning. That's because the year before Master of Reality came out, Black Sabbath's first self-titled LP, meaning-- just called Black Sabbath-- featured an upside-down cross in the gatefold sleeve, but there's one song on the album that might seem a bit out of character if Satanism was what listeners were expecting. Let's take a listen to a little bit of After Forever.

[Black Sabbath's After Forever playing]

Brian: Could it be you're afraid of what your friends might say

If they knew you believe in God above?

They should realize before they criticize

That God is the only way to love.

That's on Master of Reality. Surprising for Sabbath fans or where does the whole supposed Satanism thing come in?

Henry: If you ever [chuckles] hung out with the Black Sabbath guys I don't think you'd be thinking there's any Satan going on. I think that was just something they wrote a song about. I don't think there's any rituals or any of that. Geezer Butler wrote that lyric. I think Geezer was raised religiously, so I think that kind of pertains to his upbringing. I never bought into Black Sabbath being anything more than a rock band.

Also, those guys were really young when they wrote those songs. As a young person you can say all kinds of things and not necessarily be able to intellectually back them up or have to be all that responsible. It's not like anyone's going to lose everything because someone mentioned Satan in a song.

Brian: We've just got a few minutes left. Question about you and your relationship to this because if I understand my music history, exactly 40 years ago this month you quit your day job as head manager of Häagen-Dazs ice cream shop in DC to join the band Black Flag which is why they're considered to be one of the first hardcore punk bands. What kind of line can we draw from Black Sabbath's Master of Reality 50 years ago to punk rock and the genres that came later in the 70s and 40 years ago when you joined Black Flag? What's the legacy of the album in that lineage 50 years on?

Henry: Your last caller said he's too broke to get into the dancehall so he's outside with his friends. Black Sabbath was their band, the outsider's band. You're not the quarterback, you're not going to meet the cheerleader, Black Sabbath is your band. Look at the four members of the band. Four rough-looking guys from a tough part of England. They don't look like rock stars. They look like guys who'd punch your lights out outside of a bar. There's outsider people anywhere you look and that just describes many punk rockers.

Also, people are politically aware or ecologically aware or aware of corruption in government. Black Sabbath goes after all of that. Black Sabbath isn't afraid to say, "Not everything's going okay." Like their love songs, they're about loss. I think a lot of people would prefer the clearer lens of real-life rather than the kind of sugar water of pop music which I don't mind all the time, but a good dose of Sabbath is a good thing. I think there's a lot of parallels between the music of Black Sabbath and a lot of punk rock bands. The outsider nature, the aim at truth, not being accepted necessarily by the mainstream and not really being concerned.

Brian: We're going to go out on one last song from the album called Lord of This World. It really ties together the heavy sound and disaffected lyrics that we've been talking about. We want to thank Henry Rollins, self-described Black Sabbath advocate, formally the lead vocalist of the band Black Flag, and now host of a weekly radio show on NPR member station KCRW. Henry thanks so much for coming on this was really fun.

Henry: Thank you. Have a great weekend.

[Black Sabbath's Lord of This World playing]

Ozzy Osbourne: You're searching for your mind,

Don't know where to start.

Can't find the key,

To fit the lock on your heart.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.